Introduction

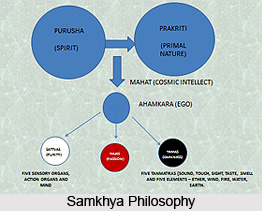

The Samkhya Philosophy or the school of enumeration is also known as Sankhya, the Sanskrit meaning of which is enumeration. It is one of the 6 schools of Indian orthodox philosophy and is believed that sage Kapila was the original founder of this school of philosophy. The Samkhya Philosophy was one of the earliest Indian attempts towards a systematic philosophy. Samkhya has two schools of philosophy - the theist school and the atheist school of philosophy. Though presently there are no purely Samkhya schools existing in Hinduism, yet its influence is felt in Yoga and Vedanta schools.

Etymology of Samkhya Philosophy

The word Samkhya is composed of 2 words sam, which means "correct or proper" and khya means "all knowing". In the context of ancient Indian philosophies, Samkhya refers to the philosophical school in Hinduism based on systematic enumeration and rational examination.

In a broader linguistic sense, ‘Saṃkhya’ (also transliterated as sankhya) is a Sanskrit term that means “to reckon,” “count,” “enumerate,” “calculate,” “deliberate,” or “reason,” including the idea of reasoning through numerical enumeration or anything relating to number and rational analysis. Within the context of ancient Indian thought, however, Samkhya refers specifically to a philosophical school in Hinduism grounded in systematic enumeration and rational inquiry.

While the word ‘Samkhya’ could earlier denote metaphysical

or empirical knowledge in a general sense, its technical use came to signify

the formal Samkhya school, which developed into a cohesive philosophical system

in the early centuries CE. The system takes its name from its central method

where it “enumerates” twenty-five tattvas, or

fundamental principles of reality. These twenty-five tattvas include ‘Purusha,’

‘Prakriti,’ and twenty-three other components of Prakriti. The ultimate aim of

this enumeration is to achieve the final liberation of the twenty-fifth tattva,

which is Puruṣha or

the soul in its original form.

Founder of Samkhya Philosophy

Sage Kapila Muni is traditionally regarded as the founder of

Sankhya philosophy. Described as a descendant of Manu, the primordial human,

and the grandson of the creator-God Brahma, Kapila is also honored as an avatar

of Lord Vishnu. In the Bhagavad Gita, he appears as a recluse endowed with

profound yogic powers and mastery of the Siddhas.

Kapila’s teachings are closely linked with yoga, and many of the philosophical insights presented in the Gita are attributed to his Sankhya framework. Renowned for his rigorous adherence to yogic discipline, he is said to have generated such intense inner heat (tapas) that he reduced the 60,000 sons of the Vedic king Sagara to ashes. A revered philosopher and teacher, Kapila inspired a lineage of disciples who went on to establish the famed city of Kapilavastu, the birthplace of the Buddha.

Many traditional sources that consistently portray Kapila as

an ascetic sage and the originator of the Samkhya school also identify Asuri as

the first inheritor of Kapila’s teachings, followed by the later scholar

Pancasikha, who is credited with systematizing the doctrine and helping to

spread it widely. Centuries later, Isvarakrsṇa is recognized for further

refining Samkhya thought by summarizing and simplifying Pancasikha’s theories,

making them more accessible to subsequent generations.

History of Samkhya Philosophy

Samkhya philosophy's earliest concepts are rooted in texts from around 500-550 BCE, although the original writings are lost. It is believed that Sage Kapila wrote two different treaties: ‘Samkhya Pravachana Sutra’ and ‘Tattwa Samasa Pravachana Sutra,’ neither of which exists today. The ‘Samkhya Pravachana Sutra’ was the first treatise in which Kapila expounded the basic concepts of the Samkhya System. In the ‘Tattwa Samasa Pravachana Sutra,’ he expanded on the theories, concerning the tattwas, or the elements and explained that creation is the result of permutation and combination of these elements.

A third generation of disciple, named Ishvara

Krishna, wrote the Samkhya Karika, which describes the entire philosophy of

Samkhya as taught by Kapila. Later, different commentaries have been written.

Gaudapada, the grand-guru of Adi

Sankaracharya, wrote a commentary called Gaudapada Karika.

Buddha had studied Samkhya with Rishi Alar Kalam and hence, Samlhya become the

base of Buddhist

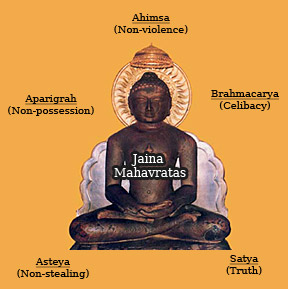

philosophy. It is also the basis for Jainism

– Mahavira’s

philosophy, also for the philosophy of Sri Krishna

in Bhagawat Gita, and for Patanjali’s

Yoga Sutra.

Objective of Samkhya Philosophy

The objective of Samkhya is to show how the creation has

evolved and how the final emancipation of the soul is to be achieved. An

attempt is made to set forth the cause of this universal bondage. According to

the Samkhya system, souls are innumerable, immaterial, unmixed, all-pervading

and inactive. The Samkhya philosophy does not recognize God’s existence. The

Sankhya system discriminates between a subtle body and a gross body. The

Sankhya system is called by the name of Mrishwar or godless.

Epistemology of Samkhya Philosophy

Samkhya’s epistemology recognizes three of the six traditional pramaṇas, namely ‘pratyakṣa’ (perception), ‘anumaṇa’ (inference), and ‘sabda’ (aptavacana, the testimony of reliable sources), as the only valid means of acquiring knowledge, a stance shared with the Yoga school. Often described as one of the rationalist traditions of Indian philosophy, Samkhya relies exclusively on reason and does not accept upamaṇa (comparison or analogy), arthapatti (postulation), or anupalabdhi (non-perception) as proper epistemic tools.

Pratyakṣa: Pratyakṣa, or perception, is one of Samkhya’s valid means of knowledge. Hindu texts describe two kinds of perception. One is external, which arises through the five senses interacting with objects, and the other is internal, which involves the mind as an inner organ of perception. Ancient and medieval sources outline four conditions for valid perception, namely ‘indriyarthasannikarṣa’ (direct contact between the senses and the object), ‘avyapadesya’ (non-verbal, meaning it cannot be based on hearsay), ‘avyabhicara’ (non-deviating, free from illusion or sensory error), and ‘vyavasayatmaka’ (definite, free from doubt and not mixed with inference or personal bias).

Anumana: Anumana, or inference, refers to deriving new conclusions from observations and established truths through the application of reason. Accepted as a valid means of knowledge in nearly all Hindu philosophical systems, it operates through a three-part structure described in classical Indian texts as pratijna (the hypothesis), hetu (the supporting reason), and dṛṣṭanta (the illustrative example).

Sabda: Sabda refers to knowledge gained through

words, specifically the testimony of reliable past or present authorities.

Schools that accept this as a valid pramaṇa argue that human beings cannot

directly learn more than a small portion of the vast truths needed for life.

This is because time and ability are limited, individuals must rely on

trustworthy sources to acquire knowledge efficiently and cooperatively, enriching

collective understanding. This knowledge is conveyed through spoken or written

words, and its validity depends entirely on the reliability of the source.

Ultimately, legitimate knowledge through sabda is believed to come from the

authoritative words of the Vedas.

Content of Samkhya Philosophy

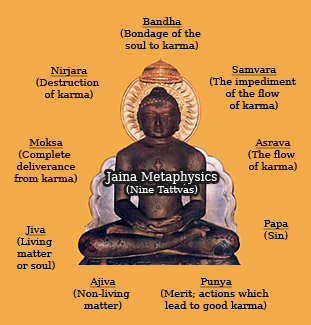

Samkhya philosophy presents a dualistic understanding of reality, grounded in two eternal and independent principles- Purusha (pure consciousness) and Prakriti (primordial nature or matter). It describes the emergence of the universe from Prakriti through the interplay of the three gunas—sattva, rajas, and tamas. Samkhya also posits the existence of countless passive Purushas, each distinct and untouched by material processes. Liberation (moksha) is attained through discriminative self-knowledge, the clear realization of Purusha’s complete separation from Prakriti.

Core Principles of Samkhya Philosophy are:

1. Dvaita Vada: Concept of Dualism

2. Purusha: Pure Consciousness

3. Prakriti: Nature / Matter and its three Gunas

4. Satkaryavada: Theory of Causation

5. Theory of Manifestation: Unification of Purusha

and Prakriti

6. Bandha: Attachment

7. Kaivalya: Liberation of the Soul

1. Dvaita Vada Or Dualism in Samkhya System

Samkhya philosophy regards the universe as consisting of two

eternal realities: Purusha and Prakriti. Purusha is the pure consciousness which has

knowledge but does not have capacity to act. Prakriti is the source of all

material existence. The Samkhya system is based on dualism wherein nature and

conscious spirit are separate entities, not derived from one another. Samkhya

is essentially atheistic because it believes that the existence of God cannot

be proved. Generally, the Samkhya system classifies all objects as falling

under one of the two categories: Purusha and Prakriti. Metaphysically, Samkhya

maintains a revolutionary duality between spirit and matter.

2. Purusha

Purusha is pure consciousness. It is eternal, permanent and unchangeable and cannot be perceived by the senses. Purusha is Chaitanya, which means self-awareness, that which is intrinsically aware, luminous and enlightened. It is beyond pain and pleasure. Purusha is desireless, it has no desire aspect. Therefore, the law of cause and effect do not bind Purusha.

3. Prakriti:

Prakṛti refers to matter or nature. It is active yet

unconscious, composed of a dynamic balance of the three guṇas—sattva,

rajas, and tamas. When Prakṛti comes into contact with Puruṣha, this

equilibrium is disrupted, setting the process of manifestation into motion and

giving rise to twenty-three tattvas. These include:

·

Intellect (buddhi or mahat)

·

Five gross elements (Mahabhutas)

- earth, water, fire, air, and space, which arise from the subtle elements

·

Five subtle elements (tanmatras) – sound, touch,

seeing / form, taste, smell

·

The sense of individuality (ahaṃkara)

·

Mind (manas)

·

Five sensory capacities (Jnanendriyas) -

hearing, touch, sight, taste, and smell

· Five action capacities (Karmendriyas) - hands (hasta), feet (pada), speech (vak), anus (guda), and genitals (upastha)

Together, these tattvas form the basis for all sensory experience, perception, and cognition.

Three Gunas in Prakriti

In Samkhya philosophy, guṇa refers to one of three inherent qualities or tendencies - sattva, rajas, and tamas. These guṇas form a foundational framework that many schools of Hinduism use to classify human behavior as well as natural phenomena. The three gunas of Prakriti are:

Sattva: Sattva represents the guṇa of balance, harmony, goodness, purity, universality, holism, creativity, positivity, peace, and virtue. It naturally gravitates toward dharma and jnana (knowledge). A person or action aligned with this quality is described as sattvik.

Rajas: Rajas is the guṇa associated with passion, activity, movement, and dynamism. It is neither inherently good nor bad, but can manifest as self-centeredness, ego, and strong individual drive. Rajas embodies the innate force behind motion, energy, and action, and is often translated as “passion” in the sense of active engagement. It plays a crucial role in actualizing and energizing the other two guṇas.

Tamas: Tamas is the guṇa associated with inaction and

ignorance. It is opposite of sattva and rajas. It manifests through dullness,

inactivity, apathy, lethargy, and sometimes through violence. Among the three

guṇas, it is generally regarded as the lowest or most limiting quality.

In prakriti, these gunas are exactly at 1/3 rd level. There

is perfect balance or equilibrium of three guna in prakriti as a whole.

4. Theory of Causation in Samkhya Philosophy

The Samkhya Theory of Causation is known as Satkaryavada.

According to which, the effect exists in its cause prior to its production. An

effect pre-exists or resides in its cause in a potential state prior to process

of manifestation. Actualization of specific effect requires a specific cause.

For e.g. to produce yoghurt, you require milk. It cannot be made from water.

This specific cause is called Shakti Karana. Further, there must be a catalyst

or an instrument to bring out the effect from the cause. This catalyst is

called Nimitta Karana. In the example of Yoghurt, curd is required as a starter

along with warm temperature. Thus curd starter and warm temperature are called

Nimitta Karana whereas Milk is called Shakti Karana. A substance in

unmanifested form is cause, whereas in the manifested form, is the effect.

The doctrine of pre-existent effect in the cause is the important part of

Samkhya. It explains that all effects are pre-existent in the cause and the

effect is the manifest cause. Nothing new is ever produced as something cannot

come out of nothing.

5. Theory of Manifestation

When purusha and prakriti are separate, there is no manifestation or movement. When purusha comes in contact with prakriti, manifestation process starts. It is similar to iron and magnet. Till the time, iron and magnet are separate, there is no movement in iron. But when magnet is brought near to iron, movement in iron starts. Prakriti is in perfect balance or equilibrium state of three gunas. When it comes in contact with purusa, this equal balance gets disturbed which leads to new permutation and combination of three gunas i.e. new creations.

The proximity of purusha to prakriti infuses prakriti with a

reflection of consciousness which is used to start the process of activity. The

conscious factor of Purusha becomes the catalyst to create the first evolute of

Prakriti i.e. Mahat, where the permutations and combinations of the gunas take

place. All gunas exist in Mahat. When sattva is predominant the qualities of

knowledge, wisdom, virtue, non-attachment and excellence manifests. When tamas

predominates, the qualities of mahat are ignorance, vice, imperfection,

attachment and impotence. Rajas vitalizes the process.

Mahat or buddhi is responsible for emergence of ego. The first self-awareness

develops in buddhi and as a sense of identity, ahamkara, the ego principle

arises. Different permutation and combination of gunas give rise to different

units / ahamkaras. That is why two individuals or elements of nature are never

exactly same. When ahamkaras are sattvic, it gives rise to knowledge, wisdom,

excellence etc., but it is opposite when ahamkaras are tamasic.

With the jnanendriyas, humans derive understanding through seeing, hearing, smelling, tasting and touching. This understanding gets stored in unconscious mind / ego in the form of impression or sanskaras. Based on this accumulated samskaras and impressions, buddhi decide about the reaction to any situation. This reaction gets executed by manas through karmendriyas, which transforms into tanmatras and mahabhutas.

Thus, the permutation and combination of three gunas (sattva, rajas and tamas) are changed every moment internally as well as externally. This gives rise to different experiences and forms.

Manifestation of elements: Tamasic ahamkaras are responsible for the manifestation of elements. These elements are either gross or subtle. The gross elements are mahabhutas and subtle elements are known as tanmataras.

From the tanmatra of sound comes the mahabhuta of space.

From tanmatara of sound and touch, the mahabhuta of air emerges. From tanmatra

of sound, space and form, the mahabhuta of fire emerges. From tanmatra of

sound, touch, form and taste, the mahabhuta of water emerges. From tanmatra of

sound, touch, form, taste and smell, mahabhuta of earth emerges. It is

important to note that three gunas exists in all tanmatras but in different

proportion.

6. Bondages / Bandha

Whenever three gunas are active, there is a disharmony. And dealing with the disharmony causes struggle or pain. The pain can steam from material causes, personal causes or cosmic or divine influences.

Humans interact with pain and pleasure as the samskara or

impressions stored in their ahamkara / ego. Then, humans end up either getting

attached to it (if it is a pleasure) or getting detached to it (if it is pain),

This gives rise to raga or dvesha. Thus, humans further get entangled in karma.

The association of Purusha with Prakriti causes bondage through false identification. It is like reacting to a dream. In a dream that somebody is chasing you with stick to hit you, you experience fear and anxiety. But when you wake up, you realize that it was just a dream and your anxiety is vanished.

This bondage can be understood with another example. When we

are sitting alone in the room and introspect, then we are absorbed in the

thoughts. We are focused on our thoughts. But when somebody comes in the room

and start communicating with us, we get involved in that. At this point our

mind and jnanedriyas get attached to that communication. Thus, with every activity,

these bondages get strong and these samakaras forms our sense / ahamkara. In

this way, Purusha becomes totally identified with buddhi and ahamkaras. Thus,

all subsequent actions are performed with that attachment and hence, the person

is not able to see the things as it is.

7. Kaivalya / Liberation

At the time of reversal or dissolution, all the five

mahabhootas, five tanmatras, the five karmendriyas, five jnanendriyas and manas

merge back into ahamkara. Then ahamkara merges back into mahat and mahat merges

back into Prakriti. Kaivalya or separation of Purusha from Prakriti then takes

place. This is achieved by complete concentration / samadhi. At this point, one

achieves many siddhis. He gets the knowledge of past, present and future.

Samkhya explains that repeated contemplation and practices are necessary to attain higher knowledge. And then Purusha re-establish itself in the original state of pure consciousness.

It is important to note that even after kaivalya, one continues to live on. The karma accumulated from the past have to be discharged, so that the body lives. After kaivalya, when one continuously contemplates, then his subsequent actions are performed in detached way which does not generate any bondage or re-action. However, past balance karmas / samskaras has to be discharged and that is the way body continues. The moment past karmas are exhausted, the Purusha is separate from Prakriti and rests in its original state of pure consciousness.

This accumulation of samakaras and its deletion can be

explained with the example of black board. If the black board is full of

writings on different subject, we do not get clarity about any single subject.

Our mind is full of different thoughts / impression / samskaras. When we become

introvert and practice meditation, new writing is stopped. And gradually, we

wipe out old samskaras one by one. As the whole writing on the board cannot be

wiped out with single wipe, the samskaras cannot be removed in one birth. With

each wipe we erase some content on the board, same way when we maintain

detached state, in each life we remove old karmas / samskaras. If this state of

detachment with contemplation is continuous, all old samskaras are removed, as

with multiple wipes, at the end, the entire board becomes clear. At this time,

the purusha rests in its original state.

Various Influences of Samkhya Philosophy

Samkhya philosophy has also influenced many ancient theories of soul in Vedic as well as non-Vedic texts. The mention of the ideas, developed under Samkhya philosophy, has been found in the early Hindu scriptures like Bhagavad Gita, Upanishads and Vedas. Samkhya philosophy has also influenced Buddhist and Jain concepts.

Influence on Buddhism and Jainism

Jainism underwent major reorganization in the 9th century BCE, and Buddhism emerged in eastern India by the 5th century BCE. It is likely that these traditions, together with the earliest forms of Samkhya, interacted and influenced one another. One notable parallel between Buddhism and Samkhya is their shared emphasis on suffering (dukkha) as a core concern in developing their soteriological frameworks, a focus far more pronounced than in many other Indian philosophical systems. In fact, the centrality of suffering in later Samkhya texts suggests that this emphasis may have been shaped, at least in part, by Buddhist thought.

Similarly, the Jain doctrine of the plurality of individual souls (jiva) may have informed Samkhya’s conception of multiple purushas. Yet, it is unlikely that the Samkhya idea of numerous puruṣhas depended solely on the Jain notion of jiva. Instead, Samkhya was more plausibly shaped by a wider range of ancient theories about the soul found across both Vedic and non-Vedic traditions.

The 12th chapter of the Buddhacharita, a Buddhist text

composed in the early second century CE, indicates that the Samkhya school had

already developed its philosophical methods of reliable reasoning by around the

5th century BCE. This suggests that key elements of Samkhya’s analytical

approach were firmly established long before the text was written.

Influence on Upanishad

The Katha Upanishad (5th–1st century BCE) presents an early conception of Puruṣha along with several ideas that later became central to Samkhya philosophy. The Shvetashvatara Upanishad also references Samkhya, pairing it with Yoga to explore metaphysical and spiritual themes. In the Katha Upanishad, Purusha, the cosmic spirit or pure consciousness, is envisioned as identical to the individual soul (Atman, the Self), reflecting an early articulation of ideas that later evolve within the Samkhya system.

Major Upanishads written in 900-600 BCE has speculations

similar to the classical Samkhya philosophy. The concept of ahamkara

has been illuminated in Chandogya Upanishad and Brhadaranyaka Upanishad. The idea of

pure consciousness was developed by Upanishadic sages, Yajnavalkya

and Uddalaka Aruni. Samkhya has enumeration of tattvas which can be traced in Taittiriya Upanishad, Brihadaranyaka

Upanishad and Aitareya Upanishad.

Influence on Bhagavad Gita and Mahabharata

The Bhagavad Gita associates Samkhya with the pursuit of understanding or true knowledge. While it also discusses the three guṇas, it does not employ them in the same technical sense later found in classical Samkhya. Instead, the Gita weaves Samkhya principles into a broader synthesis that includes the devotional (bhakti) orientation of theistic traditions and the notion of the impersonal Brahman central to Vedanta.

The Mokshadharma section of the Shanti Parva in the Mahabharata, composed between 400 BCE and 400 CE, further elaborates Samkhya concepts alongside other philosophical viewpoints. This chapter also honors a range of thinkers for their contributions to Indian philosophical thought, and among them are at least three figures associated with early Samkhya- Kapila, Asuri, and Pancasikha.

Samkhya may have begun with both theistic and non-theistic interpretations, but by the time its classical form was systematized in the early first millennium CE, the question of a deity had become largely irrelevant to its framework. Closely linked to the Yoga school of Hinduism, Samkhya provides the theoretical foundation upon which Yoga philosophy is built, and its ideas have significantly influenced several other Indian philosophical traditions.

Other Influences of Samkhya Philosophy

The Indra-Vritra myth of Rig Veda,

compiled in second millennium BCE, also has the mention of dualism. The hymns

of Purusha sukta and the emphasis of duality in the Nasadiya sukta of Rig Veda

have been influenced by this philosophy. Hymns of the Atharvaveda also

mention the concept of Purusha.