Introduction

Upanishads comes from the Sanskrit word Upa-ni-shad meaning to sit beside. In ancient times, students used to sit near the teacher for learning hence the term Upanishad. The dictionary meaning of the term is `secret doctrine`. The Upanishads are a part of the Hindu scriptures. Upanishad represents the deep Indian philosophy, the aura of meditation, the halo of religion and the indeed the nature of God. The Upanishads teamed with the philosophy of Vedanta are always regarded as a class of literature that is independent of the Vedic hymns and the Brahmanas.

Upanishads comes from the Sanskrit word Upa-ni-shad meaning to sit beside. In ancient times, students used to sit near the teacher for learning hence the term Upanishad. The dictionary meaning of the term is `secret doctrine`. The Upanishads are a part of the Hindu scriptures. Upanishad represents the deep Indian philosophy, the aura of meditation, the halo of religion and the indeed the nature of God. The Upanishads teamed with the philosophy of Vedanta are always regarded as a class of literature that is independent of the Vedic hymns and the Brahmanas.

Origin of Upanishads

The origin of Upanishad is deeply rooted in antiquity. It is said that with the growth of the caste system and with the introduction of varied styles of worship, the Kshatriya started rebelling against the usual practice of the priests. The Kshatriyas believed that most of the worship styles were corrupt and can never lead to the true path of self development. To gain knowledge and indeed to figure out the right path of self development the Kshatriyas then went into the forest to find the Rishis whom they believed to guide them towards the right path. They are undoubtedly the oldest and the most authoritative sources of Indian philosophy. The earliest of the Upanishads date back to the pre-Buddhist era and there are a few Upanishads that were written after the coming of Lord Buddha. The most possible time for the composition of those Upanishads is in between the completion of the Vedic hymns and the rise of Buddhism, in the sixth century B.C. There are also some dates available for the earliest Upanishads and the accepted dates for these Upanishads are 1000 B.C to 300 B.C.

Date of Upanishads

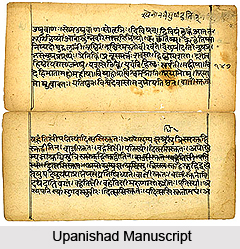

There are a number of 108 Upanishads recognized in the Indian Philosophy, available from the ancient time and the famous saint; Samkara has made his comments on about ten of them that are considered as the chief Upanishads. Though, no exact date can be assigned to the Upanishads, these are undoubtedly the oldest and the most authoritative in the Indian philosophy. The earliest of the Upanishads date back to the pre-Buddhistic era and there a few Upanishads that were written after Buddha. The most possible time for the composition of those Upanishads is in between the completion of the Vedic hymns and the rise of Buddhism, in the sixth century B.C. There are also some dates available for the earliest Upanishads and the accepted dates for these Upanishads are 1000 B.C to 300 B.C. The popular religious teacher, Samkara did make his comments on about ten of the Upanishads that were composed at a later period, during the pre-Buddhistic period of about 400 or 300 B.C.

There are a number of 108 Upanishads recognized in the Indian Philosophy, available from the ancient time and the famous saint; Samkara has made his comments on about ten of them that are considered as the chief Upanishads. Though, no exact date can be assigned to the Upanishads, these are undoubtedly the oldest and the most authoritative in the Indian philosophy. The earliest of the Upanishads date back to the pre-Buddhistic era and there a few Upanishads that were written after Buddha. The most possible time for the composition of those Upanishads is in between the completion of the Vedic hymns and the rise of Buddhism, in the sixth century B.C. There are also some dates available for the earliest Upanishads and the accepted dates for these Upanishads are 1000 B.C to 300 B.C. The popular religious teacher, Samkara did make his comments on about ten of the Upanishads that were composed at a later period, during the pre-Buddhistic period of about 400 or 300 B.C.

The Upanishads that are in prose are considered as the oldest ones and all of them are non-sectarian. To name some of the early Upanishads, the likes of the Aiterya, the Kausitaki, the Taittiriya, the Chandogya, the Brhadaranyaka, and parts of the Kena, can be mentioned. The verses 1-13 of the Kena, and iv, 8-21 of the Brhadaranyaka are considered to form the transition to the metrical Upanishads and they also can be put down as later additions. However, the Kathopanishad is considered as the later one and the elements of the Samkhya and the Yoga systems can be found here. The Kathopanishad also have frequent quotes from the other Upanishads and also from the Bhagavad-Gita. The Mandukya Upanishad is the latest one among the pre-sectarian Upanishads and it contains the elements of both the Samkhya and the Yoga systems. Apart from this, the Atharva-Veda Upanishads are also considered to grow at a later period. Among the other Upanishads, the Svetasvatara is known to be composed at such a period, when a number of philosophical theories were fermenting in India.

Early Upanishads

The Early Upanishads are those works of the Upanishads which belong to the various Vedic schools. In fact, they form only component parts of the Brahmanas. The early Upanishads include the Aitareya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittiriya, Kausitaki and Kenopanishad. The Aitareya Aranyaka, in which the Aitareya Upanishad is included, is tacked on to the Aitareya Brahmana of the Rig Veda. The Kausitaki Brahmana, which also belongs to the Rig Veda, ends with the Kausitaki Aranyaka, of which the Kausitaki Upanishad (also called the Kausitaki-Brahmana Upanishad) forms only a part.

The Early Upanishads are those works of the Upanishads which belong to the various Vedic schools. In fact, they form only component parts of the Brahmanas. The early Upanishads include the Aitareya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittiriya, Kausitaki and Kenopanishad. The Aitareya Aranyaka, in which the Aitareya Upanishad is included, is tacked on to the Aitareya Brahmana of the Rig Veda. The Kausitaki Brahmana, which also belongs to the Rig Veda, ends with the Kausitaki Aranyaka, of which the Kausitaki Upanishad (also called the Kausitaki-Brahmana Upanishad) forms only a part.

In the Black Yajur Veda the Taittiriya Aranyaka is only a continuation of the Taittiriya Brahmana, and the conclusion of the Aranyaka is formed by the Taittiriya Upanishad and the Maha Narayan Upanishad. In the great Satapatha Brahmana of the White Yajur Veda, the first third of Book XIV is an Aranyaka, while the end of the book is formed by the greatest and most important of all Upanishads, the Brhadaranyaka Upanishad. The Chandogya Upanisad , the first section of which is nothing but an Aranyaka, belongs to a Brahmana of the Sama Veda, probably the Tandya Maha Brahmana. The so-called Jaiminiya Upanishad Brahmana is an Aranyaka of the Jaiminiya or Talavakara School of the Sama Veda, and the Kenopanishad, also called Talavakara Upanishad, forms a part of it.

With, the exception of the Maha Narayana Upanishad, which was only added to the Taittiriya Aranyaka at a later period, all the above-named Upanishads belong to the oldest works` of this kind.

Literary Style of Early Upanishads

In language and style they resemble the Brahmanas, component parts of which they are, or to which they are immediately attached. It is the same simple prose, but- especially in the narrative portions- by no means lacking in beauty. Although each one of the great Upanishads contains the earlier and later texts side by side, the age of each individual piece must be determined separately. Yet even the later portions of the above-mentioned Upanishads may claim great antiquity, if only on linguistic grounds.

It may be taken that the greater Upanishads, like the Brhadaranyaka and the Chandogya Upanishad, originated in the fusion of several longer or shorter texts which had originally been regarded as separate Upanishads. This would also explain the fact that the same texts are sometimes to be found in several Upanishads. The individual texts, of which the greater Upanishads are composed, all belong to a period which cannot be very far removed from that of the Brahmanas and the Aranyakas, and is before Lord Buddha and before Panini. For this reason the six above-mentioned Upanishads- Aitareya, Brhadaranyaka, Chandogya, Taittiriya. Kausitaki and Kena- undoubtedly represent the earliest stage of development in the literature of the Upanishads. They contain the so-called Vedanta doctrine in its pure, original form.

Later Upanishads

The later Upanishads are those of the few Upanishads which are written entirely or for the most part in verse, and belong to a period which is somewhat later, though still early, and probably pre-Buddhistic. These, too, are assigned to certain Vedic schools, though they have not always come down as portions of an Aranyaka. In this category one may include the Kathaka or Katha Upanishad, the very name of which points to its connection with a school of the Black Yajur Veda. The Svetasvatara Upanishad and the Maha Narayana Upanishad which has come down as an appendix to the Taittiriya Aranyaka, are also counted among the texts of the Black Yajur Veda. The short, but most valuable Isa Upanishad, which forms the last section of the Vajasaneyi Samhita, belongs to the White Yajur Veda. The Mundaka Upanishad, and the Prasna Upanishad, half of which is in prose, half in verse, belongs to the Atharva Veda.

The later Upanishads are those of the few Upanishads which are written entirely or for the most part in verse, and belong to a period which is somewhat later, though still early, and probably pre-Buddhistic. These, too, are assigned to certain Vedic schools, though they have not always come down as portions of an Aranyaka. In this category one may include the Kathaka or Katha Upanishad, the very name of which points to its connection with a school of the Black Yajur Veda. The Svetasvatara Upanishad and the Maha Narayana Upanishad which has come down as an appendix to the Taittiriya Aranyaka, are also counted among the texts of the Black Yajur Veda. The short, but most valuable Isa Upanishad, which forms the last section of the Vajasaneyi Samhita, belongs to the White Yajur Veda. The Mundaka Upanishad, and the Prasna Upanishad, half of which is in prose, half in verse, belongs to the Atharva Veda.

Though these six Upanishads, too, contain the Vedanta philosophy, here it is found interwoven to a great extent with Sankhya and Yoga doctrines and with monotheistic views. All these texts show distinct signs of having been touched up. Though the two last-named texts must be among the latest offshoots of Vedic literature, they too may still be classed together with the twelve earlier texts as Vedic Upanishads; and these fourteen Upanishads only can be used as sources for the history of the earliest Indian philosophy.

Though the remaining Upanishads are also attributed by tradition to one or other of the Vedic schools, only a few of them have any real connection with the Veda. Most of them are religious rather than philosophical works, and contain the doctrines and views of schools of philosophers and religious views of a much later period. Many of them are much more nearly related to the Puranas and Tantras chronologically as well as in content, than to the Veda.

This latest Upanishad literature may be classified as follows, according to its purpose and contents:

1) Those works which present Vedanta doctrines,

2) Those which teach Yoga

2) Those which teach Yoga

3) Those which extol the ascetic life (Sannyasa)

4) Those which glorify Lord Vishnu and

5) Those which glorify Lord Shiva as the highest divinity,

6) Upanishads of the Saktas and of other more insignificant sects.

These Upanishads are written partly in prose, partly in a mixture of prose and verse, and partly in epic shloka. While the latter are on the same chronological level as the latest Puranas and Tantras, there are some works among the former which may be of greater antiquity, and which might consequently still be associated with the Veda. The following are probably examples of such earlier Upanishads- the Jabala Upanishad, which is quoted by Sankara as an authority, and which closes with a beautiful description of the ascetic named Paramahamsa; the Paramahamsa Upanishad, describing the path of the Paramahamsa still more vividly; the very extensive Subala Upanishad, often quoted by Ratnanuja, and dealing with cosmogony, physiology, psychology and metaphysics; the Garbha Upanishad, part of which reads like a treatise on embryology, but which is obviously a meditation on the embryo with the aim of preventing rebirth in a new womb ; and the Sivaite Atharvasiras Upanishad, which is already mentioned in the Dharmasutras as a sacred text, and by virtue of which sins can be washed away. Another factor which makes it difficult to determine the date of these Upanishads is the fact that they are often to be found in various recensions of very uneven bulk.

These non-Vedic Upanishads, as they may be called have come down in large collections which are not ancient as such. For the philosopher Sankara (about 800 A.D.) still quotes the Upanishads as parts of the Veda texts to which they belong; and even Ramanuja (about 1100 A.D.) speaks of Chandogas, the Vajasaneyins or the Kausitaki when quoting the Upanishads of the schools in question. In the Muktika Upanishad, which is certainly one of the latest, it is written that salvation may be achieved by the study of the 108 Upanishads, and a list of 108 Upanishads is set forth, classified according to the four Vedas. Upanishads coming under the Rig Veda, under the White Yajur Veda, under the Black Yajur Veda, under the Sama Veda and under the Atharva Veda. This classification, however, can scarcely be based on an ancient tradition. All these Upanishads which are, properly speaking, non-Vedic are generally called Upanishads of the Atharva Veda. These were associated with the Atharva Veda because the authority of this Veda as sacred tradition was always dubious and it was, therefore, no difficult matter to associate all kinds of apocryphal texts with the literature belonging to the Atharva Veda. Furthermore, the Atharva veda was above all the Veda of magic and the secretiveness connected with it. The real meaning of "Upanishad"- and this meaning has never been forgotten- was "secret doctrine." What was more natural than that a large class of works which were regarded as Upanishads or secret doctrines, should be joined to the Atharva Veda, which itself was indeed nothing but a collection of secret doctrines.

Types of Upanishads

However eleven principal Upanishads has been recognised. These are Katha Upanishad, Isa Upanishad, Kenopanishad, Mundaka Upanishad, Svetasvatara Upanishad, Prashnopanishad,

Mandukya Upanishad, Aitareya Upanishad, Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, Taittiriya Upanishad and Chandogya Upanishad. The names of the authors of Upanishad are not known since all the early literature of India was anonymous. The names of renowned sages like Aruni, Yajnavalkya, Balaki, Svetaketu and Sindilya are associated with the chief doctrines of the Upanishads.

Mandukya Upanishad, Aitareya Upanishad, Brhadaranyaka Upanishad, Taittiriya Upanishad and Chandogya Upanishad. The names of the authors of Upanishad are not known since all the early literature of India was anonymous. The names of renowned sages like Aruni, Yajnavalkya, Balaki, Svetaketu and Sindilya are associated with the chief doctrines of the Upanishads.

Eleven Principal Upanishads The eleven principal Upanishads are-

The eleven principal Upanishads are-

1. Aitareya Upanishad : Aitareya Upanishad is associated with Rigveda. It is short prose containing three chapters and thirty-three verses in total. Aiterya Aranyaka and aiterya Brahmana together forms Aitareya Upanishad. The first chapter ascribes atman as the divine creator, second chapter narrates the three births of atman while the third chapter deals with the quality of Brahman

2. Brhadaranyaka Upanishad : This is another older Upanishad, written by sage Yajnavalkya, which has three chapters namely, Madhu Kanda, Muni Kanda and Khila Kanda. The Madhu Kanda describes the identity of an individual and the relationship between Jiva and the Atman. Muni Kanda is the conversation between sage Yajnavalkya and his wife Maitrayee. Khila Kanda consists of the description of the different methods of worship and meditation.

3. Isa Upanishad : Isa Upanishad is the smaller Upanishad having only eighteen verses. The name of the Upanishad is derived from the sloka `Isavasyam Idam Sarvam`, which means `Supreme Lord envelops the world.`

4. Taittiriya Upanishad : Taittiriya Upanishad is the part of Krishna Yajurveda. It is divided into three parts or Vallis, namely Siksha Valli, Ananda Valli and Bhrigu Valli. Each Valli is subdividede into smaller verses called Anuvak.

5. Katha Upanishad : Katha Upanishad is also a part of Black Yajurveda. It consists of two chapters, each of which is again subdivided into three sections. Some passages of Katha Upanishad are common to Gita. It is in the question answer form where death God Yama is the teacher and young Brahman boy Nachiketa is the listener.

6. Chandogya Upanishad : Chandogya Upanishad is the last eight chapters of Chandogya Brahman. It deals with the significance of meditation and depicts the greatness of the holy syllable OM and significance of the main life force Prana.

6. Chandogya Upanishad : Chandogya Upanishad is the last eight chapters of Chandogya Brahman. It deals with the significance of meditation and depicts the greatness of the holy syllable OM and significance of the main life force Prana.

7. Kena Upanishad : The Kena Upanishad is the part of Sama Veda. It consists of four sections, the first two in verse and last two in prose. Kena Upanishad narrates the uniqueness of creation and the single power that controls the whole world.

8. Mundaka Upanishad : It is also called Mantra Upanishad as it has sixty-four Mantras in it. The Mundaka Upanishad is the part of Atharva Veda. It has two chapters and each chapter is divided into many subdivisions or Khanda.

9. Mandukya Upanishad : It is also the part of Atharva Veda. Mandukya Upanishad describes the importance of the syllable OM. It is the smallest of all the Upanishads.

10. Prasna Upanishad : The Prasna Upanishad come in the form of six question and answers asked by six disciples to the sage Pippalada about the origin, existence and destination of life.

11. Svetastara Upanishad :This is also the part of Krishna Yajurveda. It has thirteen Mantras in six chapters. The Svestara was a sage who learned this Upanishad and taught it to his disciples.

Philosophy of Upanishads

The main philosophy of the Upanishads can be put into 3 main principles:

# There is one unifying principle behind the world.

# Theory of Karma is the basis of all Indian philosophy

# Material world is never a source of happiness and permanent peace.

The philosophy of Upanishad presented some polytheistic conceptions. The Upanishads subordinated the concept of many Gods, to the One. Upanishad is the doctrine for right living. It aims to liberate the spirit from the restrains of the flesh that it might enjoy communion with God. A compromise between the philosophic faith of the few and the superstition of the crowds was thus neatly reconciled in the philosophy and mysticism of the Upanishad.

Methodology Of Upanishads

In the tranquility of forest hermitages the Upanishad thinkers excogitated on the problems of the deepest concern and communicated their knowledge to befit the requirement and necessity of the pupils near them. The visionaries of Upanishad therefore adopted a certain reticence in communicating the truth by the aura of the philosophy of Upanishad. Hence Upanishad became a name for a mystery, a secret, a discreet rahasyam, communicated only to the tested few. The methodology of Upanishad is thus unique, pointing towards the discreet communication between the Upanishad thinkers and their pupils.

In the tranquility of forest hermitages the Upanishad thinkers excogitated on the problems of the deepest concern and communicated their knowledge to befit the requirement and necessity of the pupils near them. The visionaries of Upanishad therefore adopted a certain reticence in communicating the truth by the aura of the philosophy of Upanishad. Hence Upanishad became a name for a mystery, a secret, a discreet rahasyam, communicated only to the tested few. The methodology of Upanishad is thus unique, pointing towards the discreet communication between the Upanishad thinkers and their pupils.

Upanishads have their own unique style and the systematic explanation style of Upanishad can be categorised in four different ways like dialogue with questions and answers, narration and episodes, similes, illustrations and metaphors and most importantly, symbolism. The ideal of man`s ultimate blessedness, the perfection of knowledge, the vision of the Real in which the religious hunger of the mystic for divine vision are satisfied are ideally responded amidst the unique methodology of Upanishad through the systematic style of dialogues, narratives, similes and symbolism.

This matchless methodology of Upanishad indeed ascertains the purport of the texts. The stylistic approach of dialogues with question and answer and the elaborate episodic narrations ideally unfurls the deepest truth of life in an eloquent way. On the other hand the abundant usage of the simile or illustration further aids in illustrating the meaning while throwing light on the methodology of Upanishad. The practice of investing things with symbolic meaning thus contours the base of the methodology of Upanishad while making the text a representation of the timeless truths of eternity. Symbolisms employed by the Upanishads are essentially of three types. While Nature symbolism is common in the methodology of Upanishad, it is the usage of the sacrifices and sacrificial items as symbols and the use of the mystic sound syllables (such as the Aum as symbols) silhouettes the methodology of the Upanishad.

Brahma Sutra, the aphoristic summary of the teaching of the Upanishads,

However indicates three main guidelines to understand the purport of the Upanishads:

•tattu samanvayaat.h -- The total material available on the point of study in the entire Shruti literature has to be taken into account and interpreted correctly

•gati samaanyaat.h - The entire Shruti literature has the same purport and apparent contradictions are resolved by proper study and interpretation.

•sarvavedaantapratyayam.h -- The underlying purport of the Upanishads is found to be one consistent truth, which when understood fully will lead to the realization of the Ultimate Reality.

In the midst of dialogues, symbolism and narratives what exist is an evolved methodology of teaching deeply embedded in the Upanishads which has been transmitted from one generation to the other. By this methodology of the Upanishad the student is gradually taken from where he is, to a point where he cannot but see the ultimate reality.

Monotheism in Upanishads

Monotheism in Upanishads is the basic principle according to Indian philosophers like Adi Shankracharya. It advocates delineation of the Supreme Being as the basic universal principle. The Supreme Being is called by various names like Brahman, Atma, Akshara, Akaasha, Praana and so on. The Supreme Being is the creator, destroyer, sustainer; regulator, destroyer, enlightener and liberator of all. This is the one and only independent principle upon which all the other entities are reliant. It is subjective and inspirational. It has the contradictory features of everyday experience. As it is infinite it cannot be understood completely by anyone.

Monotheism in Upanishads is the basic principle according to Indian philosophers like Adi Shankracharya. It advocates delineation of the Supreme Being as the basic universal principle. The Supreme Being is called by various names like Brahman, Atma, Akshara, Akaasha, Praana and so on. The Supreme Being is the creator, destroyer, sustainer; regulator, destroyer, enlightener and liberator of all. This is the one and only independent principle upon which all the other entities are reliant. It is subjective and inspirational. It has the contradictory features of everyday experience. As it is infinite it cannot be understood completely by anyone.

The Supreme Being has no drawbacks of any kind. It directs all and is not directed by anyone. It is independent in nature, functions and comprehension. Others derive capacities and limited qualities from it. Therefore it is also known as Sat, Chit and Ananda characteristically. The Upanishads belong to the period of fifth century. The fundamental question of this text is the relationship between God and creation, God and human beings.

Concept of Bhakti in Upanishads

Concept of Bhakti in Upanishads is mainly viewed in the context of the issue of whether or not Bhakti yoga is advocated in the Upanishads as a direct means to moksha. This is an issue mainly because of two reasons. In the first place, the term bhakti is not mentioned in the Upanishads. The texts which speak of the upaya for moksha use other terms, such as jnana, vedana, darsana, dhyana, dhruva smriti, nididhyasana and upasana. Secondly, the Upanishads also state explicitly that jnana or knowledge of Brahman is the only means to moksha. Thus says the Svetasavatara Upanishad, "Having known Him, he (the individual) transgresses death (bondage) and there is no other means to attain Him." The Taittiriya Upanishad also asserts, "He who knows Brahman attains the highest." In fact, the Advaita Vedanta maintains, on the authority of such scriptural texts, that jnana alone is the sole means to moksha. The practice of upasana or nididhyasana (meditation) referred to in other texts is considered by the Advaitin as a subsidiary means to jnana.

Regarding the first point, it may be pointed out that the term upasana bears the same meaning as bhakti. Though the term bhakti is not used in the Upanishadic texts, the concept of bhakti is implied in them. This fact is evident from the verses of the Bhagavad Gita which explicitly mention the term bhakti, while elucidating the Upanishadic text in which bhakti is implied. Thus the Mundaka Upanishad says, "This Self (Brahman) cannot be attained by the study of the Vedas, nor by meditation nor through much hearing. He is to be attained only by one whom the Self chooses. To such a person, the Self reveals Its true nature." The implication of this statement, as explained by Ramanuja, is that mere sravana (hearing), manana (reflection) and nididhyasana (meditation) undertaken without intense love for God (bhakti) cannot serve as means to attain God. Only that individual on whom God showers His grace can achieve Him. According to Ramanuja, the person on whom God chooses to shower his grace is that one who is dearest to God (priyatama eva hi varaniyo bhavati). The Bhagavad Gita provides the answer to the question as to who is the person most dear to God and why he is regarded so. Thus says the Gita. "To those who crave for eternal union (with Me) and meditate (on Me), I bestow with love that clear divine vision (buddhiyogda) by which they attain Me." It also says, "One who is most devoted to God is the one dearest to Me." By way of elucidating the statement of Mundaka Upanishad, it further points out that there is no other way of attaining God except by bhakti or intense loving meditation on God.

Further, according to Ramanuja the different terms used in the Upanishads such as upasana, dhyana, smriti santati, vedana and darsana are to be taken to mean the same as bhakti referred to in the Gita. If these terms are understood differently, it would amount to the admission of several means to moksha. Since the goal to be achieved is the same, the means cannot be different. It should, therefore, be admitted that all these terms bear the same import. According to the principle of interpretation laid down by the Mimamsaka, when different terms are used in the same context, the general term should be taken to bear the meaning of the specific term. Accordingly, in the present context, jnana, vedana, darsana, dhyana, upasana etc., are treated as general terms indicative of bhakti and bhakti as a specific term meaning unwavering devotion to God. Besides, vedana (knowledge) and upasana (meditation), which are the two key words indicating prima facie two different paths to moksha, are used in the Upanishadic passages as interchangeable words. Ramanuja, therefore, comes to the conclusion that bhakti or upasana as a spiritual discipline is the upaya to moksha.