Introduction

The ‘Yoga Sutras of Patanjali’ comprise either 195 sutras, as noted by Sage Vyasa and Krishnamacharya, or 196 sutras according to other scholars, including B.K.S. Iyengar. Compiled in India during the early centuries CE, though often associated with much older yogic knowledge, these aphorisms were gathered and systematized by the Sage Patanjali. He drew from Samkhya philosophy, Buddhist teachings, and older yogic traditions to create a unified framework of yoga practice and philosophy. Recognized by traditional Vedic schools as an authoritative source on yoga, the ‘Yoga Sutras’ reflect these three major intellectual streams dating from roughly the 2nd century BCE to the 1st century CE. In this seminal compilation, Patanjali distilled the scientific and spiritual dimensions of yoga into four distinct chapters.

Significance of Patanjali Yoga Sutras

Yoga is fundamentally a set of meditative disciplines that

aim to bring the practitioner into a state of consciousness free from active or

discursive thought. Ultimately, it seeks to cultivate a level of awareness in

which consciousness no longer perceives any external object but recognizes only

its own pure nature, unmixed with any worldly object or emotion. This state is

valued not only for its intrinsic serenity but also because its attainment is

believed to free the practitioner from all forms of material pain and

suffering.

In the broader Indic soteriological traditions, the theological study of liberation in India, is a realization that is considered a primary pathway to release from the cycle of birth and death. For this reason, the ‘Yoga Sutras’ have long been regarded across philosophical schools as the authoritative manual on meditative techniques and yogic practice. They also present the classical Indian understanding of mind and consciousness, explain the mechanisms of action and rebirth, and outline the metaphysical foundations of spiritual liberation, including the attainment of mystical powers.

About Sage Patanjali

As compared to the reputed founders of other classical schools of thought, little is definitively known about Patanjali himself. First clearly recorded in the 11th-century commentary of Bhoja Raja, Sage Patanjali is identified as the same scholar who authored the principal commentary on Paṇini’s celebrated grammar and credits him with a treatise on medicine as well.

Patanjali is also regarded as an incarnation of the serpent Ananta (meaning “endless”), the thousand-headed naga of Indian mythology who serves as Lord Vishnu’s divine couch and guardian of the world’s treasures. According to legend, wishing to share the knowledge of yoga with humanity, he descended or “fell” (pat) from heaven into the offered palms (anjali) of a woman, giving rise to the name Patanjali.

Estimates of his lifetime vary widely, ranging from the 2nd

century BCE to the 4th century CE, though many scholars today place him more

narrowly in the 2nd century CE.

Compilation of Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras

The Yoga Sutras is organized into four padas, or chapters. The first, Samadhi Pada, defines yoga as the complete cessation of all mental activity and describes the progressive stages of insight that arise from deep concentration. It ultimately points to yoga’s highest goal, which is pure, content-less awareness that surpasses even the loftiest states of insight. The second, Sadhana Pada, details the disciplines, practices, and ethical observances required for serious meditative advancement. The third, Vibhuti Pada, focuses on the extraordinary abilities that may emerge when the mind reaches profound levels of concentration. In ancient India, many practitioners pursued such powers for their own sake rather than striving for the true aim of yoga, and this chapter serves as Patanjali’s caution against being distracted by these abilities. The fourth, Kaivalya Pada, discusses liberation and its philosophical foundations.

The 195 or 196 sutras are distributed across these four

chapters: Samadhi Pada contains 51 sutras, Sadhana Pada includes 55, Vibhuti

Pada comprises 56, and Kaivalya Pada consists of 34.

Samadhi Pada

Samadhi is described as a state of direct, dependable perception (pramaṇa) in which the “seer” (Purusha—pure consciousness, the true Self) rests fully in its own nature. It is the primary method a yogi uses to still the fluctuations of the mind, ultimately leading to Kaivalya, the complete separation of the seer from the impurities and activities of the mind. In this chapter, the author explains the essence of yoga, the nature of samadhi, and the means by which it can be realized.

The core idea of this pada is “citta-vṛtti-nirodha,” the calming or restraint of the mind. Samadhi pada is essentially a guide to achieve moksha for religious practitioners who have already achieved a higher state of consciousness.

Samadhi Pada includes the following:

Sadhana Pada

Sadhana, the Sanskrit term for “practice,” is the focus of this chapter. This chapter marks the beginning of a complete guide to achieve moksha or liberation of the soul for a common human being. Here, Sage Patanjali presents two principal forms of yoga, namely- kriya yoga (the yoga of action) and ashtanga yoga (the eightfold path). Kriya yoga, often associated with karma yoga, is echoed in the philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita, where Arjuna is advised to act without attachment to the outcomes. It emphasizes selfless action and service.

Sadhana pada includes the following:

Vibhuti Pada

Vibhuti is the Sanskrit term for “power” or “manifestation.” In this third chapter, Patanjali introduces the final three limbs of Aṣṭanga Yoga, collectively known as ‘samyama.’ Through samyama, a yogi not only gains insight into pure awareness (Purusa) but may also acquire siddhis, or extraordinary abilities, that arise as the practitioner gains mastery over the tattvas, the fundamental constituents of prakriti. However, the text cautions that these powers can become obstacles for those seeking true liberation.

Vibhutis Achieved by Practicing Samyama:

Kaivalya Pada

The Kaivalya Pada is sometimes considered a later addition to the Yoga Sutras, yet it plays a crucial role in describing the nature of final liberation. Kaivalya, meaning “isolation,” refers to the complete separation of the ‘Seer’ from the contents and fluctuations of the mind, such that consciousness is no longer affected by mental activity. The term signifies emancipation or ultimate freedom and is used in contexts where other traditions commonly employ the word ‘moksha.’

This chapter explains the process through which liberation is attained and clarifies the true nature of the ‘Seer.’ Moksha represents the state of complete freedom, realizing that individual consciousness (purusha) is entirely distinct from matter (prakriti). This highest state of enlightenment involves full awareness, total detachment from suffering, and complete release from the cycle of birth and death (samsara).

Kaivalya Pada includes the following:

Yoga Sutras and Samkhya Philosophy

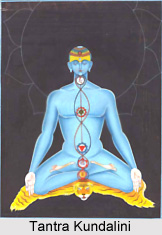

Patanjali’s metaphysics rests on the same dualistic foundation as the Samkhya school. In the Samkhya-Yoga tradition, the universe is understood as comprising two fundamental realities: puruṣha (pure consciousness) and prakriti (mind, cognition, emotions, and matter). Consciousness and matter—Self and body—are seen as entirely distinct. A living being (jiva) arises when puruṣa becomes associated with prakriti through various combinations of elements, senses, emotions, actions, and mental processes. When these components fall out of balance, or when ignorance prevails, certain constituents dominate others, resulting in bondage. The dissolution of this bondage is known as kaivalya, or liberation, equivalent to moksha in both Yoga and Samkhya.

The ethical framework of the Yoga school is grounded in the

Yamas and Niyamas and is supported by Samkhya’s Guṇa theory, which Patanjali

adopted. According to this theory, all beings embody three innate qualities (guṇas)

in varying proportions: sattva (clarity, harmony, goodness), rajas (activity,

passion, restlessness), and tamas (inertia, ignorance, chaos). An individual’s

nature and psychological tendencies are shaped by the relative dominance of

these guṇas. When sattva prevails, qualities such as wisdom, harmony, peace,

and constructive behavior arise. A predominance of rajas leads to craving,

attachment, agitation, and incessant activity. When tamas dominates, ignorance,

delusion, lethargy, destructiveness, and suffering manifest. This guṇa

framework forms the philosophical foundation for Patanjali’s understanding of

the mind in the Yoga school of Hindu thought.

Yoga Sutras and Ashtanga Yoga

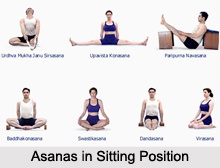

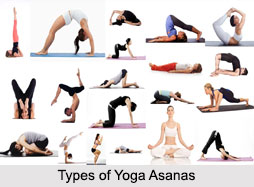

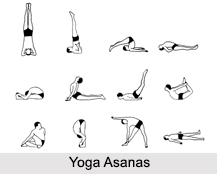

The Yoga Sutras is most widely recognized for its teachings

on ashtanga yoga, the eightfold path of practice that ultimately leads to

samadhi. These eight limbs—yama (ethical restraints), niyama (observances),

asana (posture), pranayama (breath regulation), pratyahara (sense withdrawal),

dharana (concentration), dhyana (meditation), and samadhi (complete

absorption)—outline a progressive discipline for stilling the mind. When mental

fluctuations (vritti nirodha) subside, a state known as kaivalya or “isolation”

is achieved. In this state, the practitioner directly discerns purusa (pure

consciousness, the witnessing self) as entirely separate from prakriti (nature,

including the mind and its instinctual patterns).

Yoga Sutras and Jainism

The five yamas, or ethical restraints, in Patanjali’s Yoga Sutras closely parallel the five major vows of Jainism, suggesting a historical influence. Several other ideas associated with Jain thought also appear in Yoga philosophy such as the doctrine of karmic “colors” (lesya), the goal of spiritual isolation (kevala in Jainism and kaivalya in Yoga), and the central practice of ahimsa (nonviolence). Although ahimsa is fundamental to Jainism, its earliest known expression in the sense familiar to Hinduism appears in the Upanishads. The Chandogya Upaniṣad, dated to the 8th or 7th century BCE, contains the oldest reference to ahimsa as a code of conduct, prohibiting harm toward “all creatures” (sarvabhuta). It also states that one who practices ahimsa is freed from the cycle of rebirth and identifies it as one of five essential virtues.