Introduction

Sadhana, the Sanskrit term for “practice,” is the focus of this chapter. This is the second chapter of Patanjali’s yoga sutra, comprising of 55 sutras. Here, Sage Patanjali presents two principal forms of yoga, namely- kriya yoga (the yoga of action) and ashtanga yoga (the eightfold path). Kriya yoga, often associated with karma yoga, is echoed in the philosophy of the Bhagavad Gita, where Arjuna is advised to act without attachment to the outcomes. It emphasizes selfless action and service.

Discipline for Sadhana

In Sadhana, the focus is on methods and means to attain samadhi through Kriya Yoga and Aṣhṭanga Yoga. Kriya Yoga consists of three disciplines, namely tapas (austerity), svadhyaya (self-study), and Isvara-praṇidhana (devotion to God). This collective observance is called Kriya Yoga. Kriya yoga aims to cultivate the sattvic qualities of the mind, preparing the practitioner for abhyasa (steady practice of samadhi) and vairagya (dispassion or renunciation).

Tapas: Austerity, self-discipline, and inner purification that “burns away” impurities, desires, and afflictions, thereby readying the mind for spiritual growth.

Svadhyaya: Self-study through reflection on one’s actions and engagement with sacred texts, fostering deeper self-understanding.

Isvara Praṇidhana: Devotion or surrender to God or pure consciousness, leading to meditative absorption and self-realization through complete surrender to the Divine.

Purpose of following this Discipline:

With continuous practice of Kriya Yoga with detachment, the

inclination towards Samadhi grows stronger, and at the same time, the strength

of the five afflictions (pancha kleshas) in a person gradually weakens.

Causes of Pain or Klesha

Sadhana pada identifies five types of distractions or kleshas that impede progress toward sadhana.

Five Kleshas are:

1. Avidya: Ignorance or misperception of reality,

regarded as the root of all the other kleshas.

2. Asmita: Egoism or the mistaken identification with

the individual self—the sense of “I-am-ness.”

3. Raga: Attachment or craving for pleasurable

experiences.

4. Dvesha: Aversion or repulsion toward experiences

perceived as unpleasant.

5. Abhinivesha: The instinctive fear of death or the deep-rooted clinging to life.

According to Maharshi Patanjali, Avidya is the root cause of all other kleshas. When the kleshas appear in a strong or intensified manner, they are said to be in their gross form.

Reducing or Removing Kleshas

On the yogic path, nothing is ever truly destroyed, it

simply returns to its source. Whatever arises from something ultimately merges

back into that very origin, and this natural return is what yogic tradition

calls “destruction.” With this understanding, one cultivates the vision that

all faults, impurities, negative impressions, and unhelpful habits are to be

dissolved into their root, while what is auspicious, positive impressions and

virtues, should be brought forward and expressed. This is where one should

follow the path of Kriya Yoga. When the five kleshas, along with the mind

itself, finally merge back into prakṛti (nature), the yogi becomes free from

all impurities and attains the state of Samadhi.

Removing Kleshas with Meditation

When the kleshas appear in a strong or expansive way, they

are said to be in their gross form. To address this state, one turns to Kriya

Yoga, which helps reduce their intensity and make them subtle. However, nearly

eliminating them requires a deeper, deliberate effort, which is the practice of

meditation (dhyana). The aim of this meditation is to cultivate one-pointed

awareness, bringing the chitta to a state of complete focus.

Relationship between Klesha and Karma

All karmasayas or the repositories of karma that arise from the five kleshas, beginning with ignorance (avidya), yield the results of experience (bhoga) to an individual in both the present life and those yet to come. The fruit of both negative and positive past karmas have to be experienced by the soul, if not in human form, then in other forms, be it animal or insect.

Fruit of Karma: When actions arise from the kleshas (afflictions), they leave impressions (samskaras) in the mind, and the consequences of those actions manifest as jati (birth), ayu (lifespan), and bhoga (the experience of pleasure and pain). It is important to understand that only human birth allows one to create new karmic deposits (karmasaya) while simultaneously experiencing the results of past karma, whether those actions are driven by desire (sakama) or free of desire (niṣkama). All other forms of birth are considered bhoga yonis, meant solely for undergoing the fruits of past impressions. In these states, beings simply exhaust their previous karmas and are eventually released from that particular birth.

Every birth is considered the fruit of the past karma. Karmas arising from puṇya produce pleasure, while karmas arising from papa (sin) produce pain. For a yogi, all karmic results from past and present births, whether pleasant or painful, are duḥkha or pain and he remains detached from them. Whether life brings joy or sorrow, he perceives both as forms of suffering and therefore renounces attachment to them. By seeing even pleasure as a subtle form of pain, he does not become sad, nor does he seek delight in enjoyment; he simply remains indifferent. It is here that Sage Patanjali explains how, by clearly recognizing both pleasure and pain as pain, one learns to avoid it. He also highlights that only future pain is avoidable not past or present pain.

Avoiding karmic consequences in the future: If one

engages in powerful virtuous actions, they can counteract the effects of sinful

deeds that are about to produce suffering in the future birth. A strong flow of

good deeds can obstruct impending hardship. Any effort you make to escape pain

influences only the suffering that lies ahead. Therefore, only future pain can

be prevented but pain arising from past or present actions cannot be undone.

Cause of Heya or Pain

The

fundamental cause of all sorrow is the ignorant association of puruṣha with

prakriti; their mistaken union lies at the heart of suffering. In yoga, the

root cause of heya lies in the union of the seer (dṛsṭa) and the seen (dṛsya).

It should also be understood

that all experiences of pleasure and pain arise through the physical body. Only

when all desires have been exhausted does one sincerely embrace the path of

Yoga. If one is prepared and deserving, liberation is attained and one rests in

eternal bliss. Otherwise, the seeker returns again and again, continually

seeking refuge in the yogic path.

Properties of Nature / Prakriti

Nature, in the form of Prakriti exists solely for the soul’s (Atman’s) experience (bhoga) and, ultimately, for guiding it toward freedom from all experience, which is liberation (moksa or kaivalya). The true purpose of Nature is to lead the Purusa to liberation because enjoyment is merely incidental.

Four Stages of Gunas in Prakriti

Maharshi Patanjali describes four stages of categories of

gunas in Prakriti as:

1. Viseṣa (Particulars): The five organs of knowledge, the five organs of action, the mind, and the five gross elements such as Water, Air, and Earth are called Viseṣa.

2. Aviseṣa (Generals): The five subtle elements (tanmatras) and the ego (ahankara) are called Aviseṣa.

3. Lingamatra (The mere sign): The great principle (mahat-tattva) or intellect (buddhi) is called Lingamatra.

4. Alinga (Without sign): The state of equilibrium of

sattva, rajas, and tamas is called Alinga.

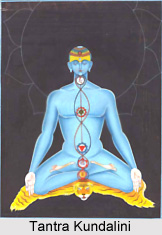

Prakriti and Seer

All inert substances forming Prakṛti (mind, intellect, consciousness, ego, senses, etc.) are called Dṛsya (the Seen), and the conscious principle (Atman, the individual soul) is called Dṛṣṭa (the Seer). The Seer is Purusha (the one who perceives), is pure knowledge. Even though the Puruṣa or Atman is eternally pure, conscious, and liberated, it still sees according to the thoughts or mental patterns arising in the chitta (mind).

Prakriti after liberation: For a yogi who has gained

true discernment and knowledge, nature completes its role in leading them to

liberation (apavarga). In such beings, the separation between prakriti and puruṣha

naturally occurs. However, for the ignorant, the unwise, and those still

progressing along the yogic path, nature does not fade away, it continues to

operate just as before.

Samyoga- Union of Purusha and Prakriti

The cause for the realization of the nature of both Prakṛti and Puruṣha (the individual soul) is their union. This union makes it possible to know the intellect (buddhi) and the self (atman) separately. Without the union of Prakṛti and Puruṣha, there would be no opportunity for a person to become aware of this union and thus to know both self and Prakṛti.

The union of Prakṛti and Purusha arises from Avidya or ignorance. It is this ignorance that brings them together, setting in motion the entire cycle of worldly existence.

Hana/ Absence of Samyoga

The state of the absence of union or samyoga is called Hana

in Yoga. It is also known as the kaivalya (absolute liberation). Until the

union between the individual soul or Purusha and Prakṛti is destroyed, the

state of Hana cannot be attained.

Attaining Hana: Hana is achieving moksha or the end

of all sufferings. The continuous realization and firmly established maturity

of discriminative knowledge, recognizing the true difference between Purusha

and Prakrti, is the path to attain hana (cessation of suffering). In this

state, Prakrti, having revealed the true nature of Puruṣha, eventually withdraws.

Stages of Enlightenment after Hana

As soon as the yogi attains hana, the state of firm, steady, and uninterrupted knowledge, a special wisdom (viseṣa prajna) descends into their intellect. His intellect becomes elevated from the ordinary to the extraordinary. Previously, the intellect led towards enjoyment and ignorance, but now it carries the Purusha only towards true knowledge.

The Path from Kleshas to Kaivalya

When the kleshas arise, a human being becomes entangled in

the cycle of birth and death, bound by the circumstances of birth, the span of

life, and the alternating experiences of pleasure and pain. Kriya Yoga offers

the means to weaken the kleshas and deepen the experience of samadhi. Through

steady practice of austerity (tapas), self-study (svadhyaya), and surrender to

God (Ishvara pranidhana), these afflictions are gradually reduced to a subtle

form. Only then should one begin the practice of Ashtanga Yoga. Without first

cultivating Kriya Yoga to a certain extent, true progress in Ashtanga Yoga

cannot be achieved.

Eight Parts of Yoga Disciplines

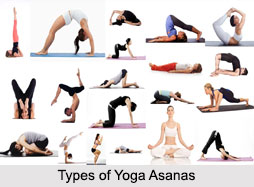

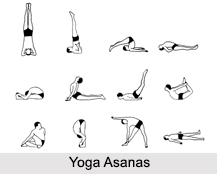

Ashtanga yoga, or the yoga of eight limbs, states five "indirect aids" for purification of the mind and soul. Eight limbs of Ashtanga Yoga are:

1.

Yama

2.

Niyama

3.

Asana

4.

Pranayama

5.

Pratyahara

6.

Dharana

7.

Dhyana

8. Samadhi

Five Yamas

The term ‘yama’ means “rein,” “curb,” “restraint,” or

“self-control.” These universal ethical principles guide how an individual

relates to the external world and other beings.

The five Yamas are:

Ahimsa (Non-violence): Avoiding harm to any living being through thoughts, words, or actions while cultivating compassion and kindness.

Satya (Truthfulness): Practicing honesty in all interactions, ensuring that truth is expressed with sensitivity and in harmony with non-violence.

Asteya (Non-stealing): Refraining from taking what is not freely given—including avoiding envy or coveting—thereby fostering honesty and contentment.

Brahmacharya (Moderation/Continence): Traditionally associated with celibacy, but more broadly referring to moderation of the senses and wise use of one’s energy.

Aparigraha (Non-possessiveness): Releasing greed and attachment to material possessions, encouraging self-reliance and inner security.

Practicing the Yamas purifies one’s actions and relationships, cultivating the mental discipline required for deeper concentration.

Five Niyamas

Niyama is the second limb of the eightfold path consists of personal observances that support inner purification and spiritual growth.

The five Niyamas are:

Saucha (Purity/Cleanliness): Maintaining physical cleanliness, mental clarity, and purity of intention.

Santosha (Contentment): Developing acceptance and gratitude, letting go of restless desires for more.

Tapas (Self-discipline/Austerity): Cultivating perseverance, discipline, and the transformative effort needed to purify mind and body.

Svadhyaya (Self-study/Reflection): Engaging in introspection and studying sacred texts to deepen self-understanding.

Ishvara Praṇidhana (Surrender to the Divine): Dedicating one’s actions to a higher power, helping dissolve ego-driven desires.

Together, the Niyamas and Yamas establish the ethical and personal foundation necessary for advanced yogic practices such as asana.

Fruits of Yamas

These are the physical and mental benefits a yogi gains by

observing all five Yamas. Among them, Ahimsa (non-violence) is placed first.

Ahimsa: Ahimsa is the foundation of all the Yamas. As the seeker becomes increasingly imbued with the spirit of non-violence, a natural inclination arises to uphold the remaining Yamas and Niyamas as well.

Satya: When a seeker becomes firmly established in truth, whatever he speaks, manifests outwardly as truth.

Asteya: Asteya means refraining from taking anything such as objects, property, wealth, or space, without the permission of its rightful owner. Not only the act of taking but even the thought of it is considered steya, or theft. When a yogi desires nothing beyond the essentials needed for his livelihood, he attains the perfection of asteya. Only the vessel that is empty of craving has the capacity to be filled.

Brahmacharya: Brahmacharya refers to preserving one’s vital energy, virya (semen) or rajas (reproductive essence). Through steadfast practice of brahmacharya, the yogi attains incomparable vitality, with every moment of life infused with fresh and ever-expanding energy.

Aparigraha: When non-possessiveness (Aparigraha) becomes firmly rooted in a yogi’s life, he gains clear knowledge of his past births, his present existence, and the potential unfolding of his future.

Fruits of Niyama:

Just like Yamas, following five Niyamas also offer some mental and spiritual benefits to the yogi.

Saucha: Until the dwelling place of the soul, the body becomes pure both outwardly and inwardly, true spiritual practice cannot begin. Through Saucha, the body is cleansed externally by daily bathing. Internally, the mind holds many impurities; purifying these through truthful conduct and similar virtues is known as inner cleanliness.

Santosha: Through contentment, the yogi attains the highest happiness. Santoṣha means utilizing one’s capacity fully and accepting wholeheartedly whatever results come, without any desire for reward.

Tapas: When the senses lack discipline, they naturally move outward. By practicing austerity and gaining control over them, the yogi increases their sattva, the quality of purity and clarity. As sattva rises, the impurities of the senses diminish.

Svadhyaya: As the yogi continues the practice of svadhyaya, deep devotion may arise toward a higher being, a deity, sage, or seer. With this devotion, divine vision begins to unfold, and the yogi becomes receptive to unseen blessings and support from those elevated beings.

Ishvara Praṇidhana: When the yogi relinquishes the

ego of individuality and aligns his life with the presence of God, his

knowledge becomes illuminated like divine knowledge, it becomes discriminative

wisdom (viveka-jnana). With the emergence of viveka-jnana, avidya (ignorance)

is destroyed. When avidya falls away, all five afflictions (pancha klesas) are

dissolved, and the yogi attains the state of samadhi.

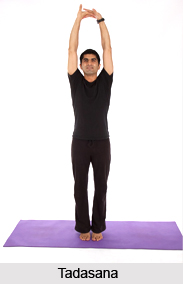

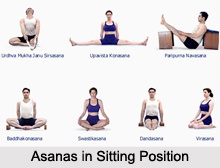

Significance of Asana in Ashtanga Yoga

Literally meaning “seat,” Asana refers to a stable (sthira) and comfortable (sukha) physical posture that allows the practitioner to sit still for prolonged periods of meditation.

The sutras refer only to seated asanas, particularly those used for praṇayama, dharaṇa, and dhyana. The yogi should choose one posture—Padmasana, Sukhasana, or Siddhasana, and then relax all physical movements and activities while settling the mind on the Infinite Supreme Being. Mastery of asana brings steadiness and comfort to the body, ensuring that in the subsequent practices of praṇayama, dharaṇa, and dhyana, the posture itself does not become an obstacle.

Praṇayama

In the Yoga Sutras, Praṇayama is presented as a method to steady the mind and cultivate concentration by regulating praṇa, the vital life force. Through mastery of the breath, one reduces inner agitation, restlessness, and indecision, creating a calm and focused state of consciousness.

When a yogi is able to sit for extended periods in Padmasana, Sukhasana, or Siddhasana with steadiness and ease, the practice of restraining the movement of inhalation and exhalation is known as praṇayama. If the yogi sits firmly, takes in a breath, and then holds it, that retention itself is called praṇayama. This practice is regarded as the highest form of austerity (tapas), for the effort required to suspend both the incoming and outgoing breath and to remain steady in that suspension, demands exceptional discipline.

Types of Praṇayama

Maharshi Patanjali has mentioned about four types of

pranayama in the sutras.

Bahyavṛtti Praṇayama: Forcefully expelling the praṇa outward and then retaining it outside is known as Bahyavṛtti Praṇayama.

Abhyantara-vṛtti Praṇayama: Drawing the praṇa-vayu inside the body through the nostrils and then holding it within is called Abhyantara-vṛtti Praṇayama.

Stambha-vṛtti Praṇayama: When, during the natural flow of breath, the yogi halts the breath exactly at its current point, whether inside or outside, it is referred to as Stambha-vṛtti Praṇayama.

Fourth type of Pranayama:

After practicing Bahya-vṛtti and Abhyantara-vṛtti, when one

resists the natural impulse to inhale or exhale, that restraint is known as the

fourth type of praṇayama.

Fruit of Pranayama

Through the practice of praṇayama, both the mind and the praṇa

come under control simultaneously, enhancing one-pointed concentration. Once a

yogi has mastered asana and then perfects praṇayama, significant progress

naturally follows in the path of yoga.

Removal of Veil from Consciousness: Through the practice of praṇayama, both the mind and the life-force (praṇa) are brought under control at the same time, leading to heightened concentration. This also cultivates a refined mastery over the senses. Once asana is firmly established and praṇayama is perfected, he gradually advances towards pratyahara, dharaṇa, and dhyana.

Enhance Concentration for Dharana: This is the second

benefit or fruit of practicing praṇayama. Through consistent practice of praṇayama,

one develops a remarkable mastery over the mind, enhancing the ability to

concentrate at will. A yogi can direct the mind’s focus toward the body or to

any external point whenever desired. This steady cultivation of concentration

is essential for reaching the higher stages of pratyahara, dharaṇa, and dhyana.

Pratyahara

Pratyahara is the withdrawal of the senses from external objects. By turning attention inward, the practitioner achieves inner stillness and prepares the mind for the deeper stages of concentration (dharana) and meditation (dhyana).

Fruit of Pratyahara

When pratyahara is perfected, the yogi gains a unique

mastery over the senses, coming very close to indriya-jaya, victory over the

senses. Indriya-jaya means directing the senses toward their objects solely

according to one’s own will. With mastery of pratyahara, the yogi no longer

gravitates toward pleasures, nor does the mind fall into distraction or

restlessness. Concentration becomes steady, and he continues along the yogic

path without obstruction.