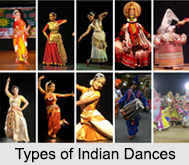

Kuchipudi dance, originally called Kuchelapuri or Kuchelapuram, is a classical dance form. From South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh it grew largely as a product of Bhakti (devotion) movement beginning in the seventh century A.D. It derives its name from the village of Kuchelapuram in Krishna district, which is a small village about 65 km from Vijayawada. Kuchipudi dance is known for its graceful movements and its strong narrative or dramatic character. The tradition of Kuchipudi dance was passed down through generations of Brahmin families in Kuchipudi village and interacted with the temple dance traditions as well as the other drama traditions of South India.

Kuchipudi dance, originally called Kuchelapuri or Kuchelapuram, is a classical dance form. From South Indian state of Andhra Pradesh it grew largely as a product of Bhakti (devotion) movement beginning in the seventh century A.D. It derives its name from the village of Kuchelapuram in Krishna district, which is a small village about 65 km from Vijayawada. Kuchipudi dance is known for its graceful movements and its strong narrative or dramatic character. The tradition of Kuchipudi dance was passed down through generations of Brahmin families in Kuchipudi village and interacted with the temple dance traditions as well as the other drama traditions of South India.

Etymology of Kuchipudi Dance

The etymology of Kuchipudi dance is closely intertwined with its geographical and historical origins. This traditional Indian dance form derives its name from the village of Kuchipudi, situated in the Krishna district of Andhra Pradesh. The name "Kuchipudi" is a shortened form of the village`s full name, "Kuchelapuram" or "Kuchilapuri," where this unique dance style took shape and evolved.

The etymological roots of the village`s name can be traced back to Sanskrit. The village of Kuchipudi, in essence, embodies its significance in its name. It is believed to have originated from the Sanskrit term "Kusilava-puram," which translates to "the village of actors." The term "Kusilava" is a word found in ancient Sanskrit texts, and it denotes individuals who played multifaceted roles as traveling bards, dancers, and bearers of news and stories.

Origin of Kuchipudi Dance

Kuchipudi dance, like other classical dance forms in India, traces its roots to the Sanskrit Natya Shastra, a foundational treatise on the performing arts. Its first complete compilation is dated to between 200 BCE and 200 CE; but the estimates vary between 500 BCE and 500 CE. The most studied version of the Natya Shastra text consists of about 6000 verses structured into 36 chapters.

During earlier days Kuchipudi dance was performed once in a year and the dance form was cautiously kept out of the reach of Devadasis. From the first performers, the technique and skills of this form got handed over to the next generations to acquire the present form. The tradition has remained so unbroken that even today in some of the coastal areas of Andhra pradesh, Kuchipudi dance is still performed by all-male troupes.

However, in modern times, women have dominated the art. Modern Kuchipudi dance acquired its present form in the 20th century. A number of people were responsible for moving it from the villages to the performance stage. Prior to this time, even as early as the 8th century, prototypes of the Kuchipudi dance drama centering on the life of Lord Shiva and other Hindu gods had been performed and was known as Nattuva Mala. Originally it was meant to be a ritualistic performance full of religious passion and devotion. Properly trained men and boys presented the dance in the open air on an improvised stage. The play began by paying respect to Lord Ganesha. In the past 30 years, the dance has undergone a revival as both a solo and dance drama tradition and is now performed on the modern stage around the world by both men and women.

History of Kuchipudi Dance

The history of Kuchipudi dance is rooted in the ancient traditions of Andhra Pradesh, showcasing a rich cultural heritage that has evolved over centuries. This dance-drama tradition finds its origins in the Andhra region, as noted by Bharata Muni, who credited this graceful movement as "Kaishiki vritti." Even in pre-2nd century CE texts, there is reference to a raga named "Andhri," which is linked to Andhra. This raga, with connections to Gandhari and Arsabhi, is discussed in various 1st millennium Sanskrit texts. Some scholars even trace the origins of Kuchipudi back to the 3rd century BCE.

Evidence of dance-drama performance arts related to Shaivism in Telugu-speaking parts of South India can be found in 10th-century copper inscriptions. These performances were referred to as "Brahmana Melas" or "Brahma Melas," and the artists involved were predominantly Brahmins during the medieval era. It is likely that this art form was adopted by the musical and dancing Bhakti traditions of Vaishnavism, which flourished in the 2nd millennium. In the Andhra region, devotees of this tradition were known as "Bhagavatulu," while in the Tamil region of South India, they were called "Bhagavatars." In Andhra, this performance art evolved into what we now recognize as Kuchipudi, whereas in Tamil Nadu, it took the form of "Bhagavata Mela Nataka."

The modern version of Kuchipudi is largely attributed to Tirtha Narayanayati, a 17th-century Telugu sanyasin (ascetic) of the Advaita Vedanta persuasion. It was his disciple, a Telugu Brahmin orphan named Sidhyendra Yogi, who played a pivotal role in shaping Kuchipudi as we know it today. Tirtha Narayanayati authored "Sri Krishna Leela Tarangini," a significant work in which he introduced sequences of rhythmic dance syllables at the end of the cantos, envisioning it as a libretto for a dance-drama. During his lifetime, Narayanayati resided in the Tanjore district and presented his dance-drama in the Tanjore temple.

Following in the footsteps of his guru, Sidhyendra Yogi composed another play called "Parijatapaharana," more commonly known as the "Bhama Kalapam." However, when Sidhyendra Yogi completed the play, he encountered difficulties in finding suitable performers. In search of talent, he journeyed to Kuchelapuram, the village of his wife`s family, which is now known as Kuchipudi. Here, he enlisted a group of young Brahmin boys to perform his play. This tradition was further established when Sidhyendra requested and received the villagers` agreement to perform the play annually, ultimately giving rise to the name "Kuchipudi" for this distinctive dance-drama form.

Kuchipudi in Late Medieval Period

During the late medieval period, Kuchipudi experienced both patronage and challenges that shaped its trajectory. Kuchipudi enjoyed significant support from rulers during this era. Copper inscriptions provide evidence that by the early 16th century, this dance-drama had already gained recognition among the royalty and had a considerable influence. The court records of the Vijayanagara Empire, renowned for its patronage of the arts, reveal that drama-dance troupes of Bhagavatas from the village of Kuchipudi performed at the royal court. However, historical inscriptions also hint at an even earlier origin, tracing the roots of this art form back to the first century BCE.

The late medieval period in the region was marked by wars and political upheaval, particularly due to Islamic invasions and the emergence of the Deccan Sultanates in the 16th century. With the decline of the Vijayanagara Empire and the devastating impact of the Muslim army`s actions on temples and Deccan cities around 1565, musicians and dance-drama artists sought refuge by migrating southward. Records from the Tanjore kingdom indicate that approximately 500 such Kuchipudi artist families arrived from Andhra and were welcomed by the Hindu king Achyutappa Nayak. They were granted land, and their settlement eventually evolved into modern-day Melattur, near Tanjore, which is also known as Thanjavur. However, not all practitioners left the original Andhra village of Kuchipudi, and those who remained became the sole custodians of the Kuchipudi tradition in the Andhra region.

By the 17th century, Kuchipudi faced a period of decline and was on the verge of becoming a dying art in Andhra. However, in 1678, a pivotal event occurred when Abul Hasan Tana Shah, the last Shia Muslim Sultan of Golkonda, witnessed a Kuchipudi performance and was immensely pleased by it. As a gesture of his appreciation, he granted lands to the dancers around the Kuchipudi village, with the condition that they would continue to practice and perform the dance-drama. It`s worth noting that the Shia Sultanate came to an end in 1687 when the Sunni Mughal Emperor Aurangzeb took control.

Aurangzeb`s reign brought significant challenges to Kuchipudi and other performing arts. In his efforts to regulate public and private morals and eliminate practices considered un-Islamic, Aurangzeb banned public performances of all music and dance arts. Furthermore, he ordered the confiscation and destruction of musical instruments across the Indian subcontinent under the control of his Mughal Empire. This ban had a profound impact on the practice and propagation of Kuchipudi during this period.

Kuchipudi in Colonial Period

During the colonial period, Kuchipudi faced significant challenges and cultural discrimination. The colonial era in India unfolded in the wake of the collapse of the Mughal Empire following the death of Aurangzeb in 1707. This period saw the emergence of Hindu rebellions in various parts of the country, including the Deccan region. It was during the latter half of the 18th century that colonial Europeans arrived in India, and the Madras Presidency was established by officials of the East India Company, eventually becoming a part of the British Empire. Andhra was included within the Madras Presidency.

Throughout the colonial era, Hindu arts and traditions, such as dance-drama, were subjected to ridicule and denigration. Christian missionaries and British officials propagated derogatory stereotypes about dancers and portrayed Indian classical dances as evidence of a culture characterized by "harlots, debased erotic culture, slavery to idols, and priests." In 1892, Christian missionaries initiated the "anti-dance movement" with the aim of banning all classical Indian dance forms. This movement went so far as to accuse various classical Indian dance forms of being a front for prostitution. Concurrently, revivalists challenged the historical narratives constructed by colonial writers.

In a significant development in 1910, the Madras Presidency of the British Empire issued a comprehensive ban on temple dancing. Kuchipudi, traditionally performed at night on stages attached to Hindu temples, was profoundly affected by this ban. Consequently, like all classical Indian dances, Kuchipudi witnessed a decline during the colonial rule.

However, in response to the cultural caricatures and discrimination perpetuated during this period, many Indians began to protest and take action to preserve and rejuvenate their cultural heritage. These efforts, which gained momentum in the 1920s, marked a renaissance for classical Indian dances. An influential figure in this revival was Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri (1886–1956). Sastri played a pivotal role in the preservation, reconstruction, and revival of Kuchipudi performance art. He collaborated closely with other revivalists during the period between 1920 and 1950, including Balasaraswati and others who were equally determined to safeguard and revive Bharatanatyam, another classical Indian dance form.

Kuchipudi in Modern Period

In the modern period of Kuchipudi, spanning the first half of the twentieth century and beyond, several influential figures played pivotal roles in the preservation, promotion, and evolution of this classical Indian dance form. Three prominent figures during this era were Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri, Vempati Venkatanarayana Sastri, and Chinta Venkataramayya. Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri emerged as a key figure in the revival and renaissance of Kuchipudi. He took up the task of re-launching Kuchipudi at a time when classical Hindu dances faced sustained ridicule and political degradation during the British Raj. Sastri`s efforts were instrumental in bringing Kuchipudi back into the limelight. Chinta Venkataramayya, on the other hand, made significant contributions to the production of Kuchipudi performances for public audiences. He also played a vital role in the development of specialized forms of Yakshagana, another classical Indian dance, in addition to Kuchipudi. Sastri`s legacy includes his encouragement of Indian women to embrace Kuchipudi, both as solo performers and in group settings, while also fostering collaborations with artists from other classical dance forms, such as Bharatanatyam, thereby facilitating the exchange of ideas and artistic influences.

Vempati Venkatanarayana Sastri, the guru of Vedantam Lakshminarayana Sastri, played a significant role in preserving and passing down the tradition of Kuchipudi. His teachings not only imparted the art of Kuchipudi to his disciples but also contributed to its continuity.

A milestone moment in the modern history of Kuchipudi was the historic All India Dance Seminar held in 1958. Organized by the national arts organization Sangeet Natak Akademi, this seminar brought Kuchipudi to the national stage, furthering its recognition and importance in the realm of Indian classical dance.

The preservation of Kuchipudi was not limited to Indian dancers alone. Western dancers also joined the effort to save and revive classical Indian dances. An example is Esther Sherman, an American dancer who moved to India in 1930, adopted the name Ragini Devi, and became actively involved in the movement. Her daughter, Indrani Bajpai (Indrani Rahman), received training in Kuchipudi and achieved acclaim as a celebrated Kuchipudi dancer. The performances of Kuchipudi by artists like Indrani Rahman and Yamini Krishnamurti, both within and outside the Andhra region, ignited wider enthusiasm and interest in the dance form. This led to the expansion of Kuchipudi as a creative performance art, gaining recognition not only within India but also on the international stage.

The latter half of the twentieth century was marked by the dominance of the Kuchipudi school of Vempati Chinna Satyam. His efforts focused on further codifying the modern repertoire of Kuchipudi, earning him multiple accolades, including the prestigious Padma Bhushan.

Kuchipudi also found its way into the world of Indian cinema, with actresses like Hema Malini commencing their careers as Kuchipudi and Bharatanatyam dancers. As a result of these collective efforts and contributions, Kuchipudi performances have now transcended geographical boundaries and gained global recognition. A notable achievement was the largest group performance, involving a total of 6,117 dancers, in Vijayawada, which secured a place in the Guinness World Records, showcasing the enduring appeal and significance of Kuchipudi on the world stage.

Repertoire in Kuchipudi

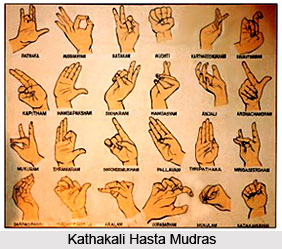

Kuchipudi relies heavily on expressive gestures of the hands (mudras), eye movements, and facial expressions to convey the underlying drama. The expressive style of Kuchipudi is governed by a sign language derived from classical pan-Indian Sanskrit texts such as Natya Shastra, Abhinaya Darpana, and Nrityararnavali. Accompanied by Carnatic music, the recital is conducted in the Telugu language.

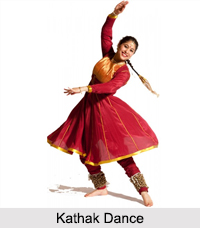

Kuchipudi shares common postures and expressive gestures with Bharatanatyam, such as the Ardhamandali (a half-seating position or partial squat with bent knees). However, it distinguishes itself through its inclination towards sensuality, suppleness, and folk elements, in contrast to the more spiritually inclined and geometrically perfect traditions of Bharatanatyam, which are often associated with Hindu temple rituals.

The repertoire of Kuchipudi, like other major classical Indian dance forms, adheres to the three categories outlined in the ancient Hindu text, Natya Shastra: Nritta, Nritya, and Natya. Nritta, the abstract and fast-paced aspect of Kuchipudi, focuses on pure movement, emphasizing the beauty of motion, form, speed, range, and pattern. This technical performance aims to engage the audience`s senses without narrating a specific story.

Nritya, on the other hand, is the slower and more expressive facet of Kuchipudi. It seeks to convey emotions and narratives, often delving into spiritual themes from Hindu traditions. In Nritya, the dancer uses gestures and body movements synchronized with musical notes to articulate a story or convey a spiritual message, aiming to engage the audience`s emotions and intellect.

Natyam, the final category, is a dramatic play typically performed by a team of dancers, although solo or duo performances are not uncommon in contemporary Kuchipudi productions. In Natyam, standardized body movements are employed to signify different characters within the overarching story, incorporating elements of Nritya.

Performance of Kuchipudi

Performance of Kuchipudi

Performance in Kuchipudi encompasses a meticulously structured sequence, incorporating both nritta and nritya in solo or group presentations, and potentially featuring a natya when the underlying text is a dramatic play. The nritta component of Kuchipudi comprises abstract dance segments, which can include darus, jatis, jatiswarams, tirmanas, and tillanas, each contributing to the rhythmic and expressive dimensions of the performance. On the other hand, the nritya or expressive facet of Kuchipudi comprises padams, varnams, shabdams, and shlokas, designed to convey narratives and emotions.

Traditionally, a Kuchipudi performance is conducted during the evening, allowing rural audiences to gather after their daily farm activities. Commencing with an invocation, known as melavimpu or puvaranga, the performance may commence with an onstage prayer to Lord Ganesha, symbolizing auspicious beginnings, or express reverence to various Hindu deities, the Earth, or the guru (teacher).

The conductor of the performance makes a grand entrance and places an "Indra`s banner" staff on stage. Subsequently, all actors and their respective characters are introduced, concealed behind a curtain. As each actor is unveiled, colored resin is thrown into the torch flames for dramatic visual effects, capturing the audience`s attention. A short dance called the Pravesa Daru, accompanied by a musical piece and a vocal description of the character`s role, is performed by each actor. Throughout the performance, the conductor remains onstage, elucidating the play, engaging with the audience, and infusing humor into the proceedings.

Following the introduction of the actors, the nritta segment of the Kuchipudi performance commences. In this phase, the actors present a pure dance, known as jatis or jatiswarams, characterized by rhythmic movements synchronized to a musical raga. These dances, referred to as Sollakath or Patakshara, are structured around fundamental dance units called adugu (or adugulu). These adugulu combine hand and foot movements into graceful sthanas (postures) and charis (gaits), visually captivating the audience regardless of their vantage point. According to ancient texts, each basic unit is best performed with specific mnemonic syllables and musical beats. A series of karana, akin to Sanskrit mnemonics, form a jati, laying the foundation for the nritta sequence in Kuchipudi.

The subsequent phase, nritya, is the expressive heart of the performance, involving abhinaya, wherein the actor-dancer employs hand mudras and facial expressions derived from ancient Sanskrit texts` sign language. A solo performance or solo section, known as Shabdam, may be set to poetry, verses, or prose. Varnam, a blend of dance and mime, draws out and expresses the rasa (emotional essence) and can be performed individually or by a group. Parts set to poetic expressions of love or deeper sentiments are referred to as padam, encompassing the emotional, allegorical, and spiritual dimensions of the play. Unique to Kuchipudi are the Kavutvams, which can be presented as either nritta or nritya, accompanied by different talas (rhythmic patterns). These segments incorporate acrobatics, elevating the complexity of the performance.

Style of Kuchipudi Dance

The style of Kuchipudi dance exhibits a rich tapestry of regional variations, known as banis, which have evolved over time, owing to the distinctive and innovative approaches of its revered gurus (teachers). This spirit of openness and flexibility has deep historical roots within the broader Indian dance culture and can be traced back to the early days of Kuchipudi, as evidenced by the Margi and Desi styles documented in Jaya Senapati`s Nrittaratnavali.

The foundation of these dance styles is rooted in the principles articulated in standard treatises such as the Abhinaya Darpana and Bharatarnava by Nandikeswara, further sub-divided into Nattuva Mala and Natya Mala. Nattuva Mala, in particular, assumes two forms: the Puja dance, performed at the sacred Balipitha within the temple precincts, and the Kalika dance, conducted within a Kalyana Mandapam. On the other hand, Natya Mala encompasses three distinct types: ritual dance dedicated to deities, Kalika dance catering to intellectual sensibilities, and Bhagavatam, which is more accessible and resonates with common audiences.

Technique of Kuchipudi Dance

Kuchipudi dance styles are based on Abhinaya Darpana and Bharatarnava of Nandikeshwara, which are then sub-divided into Nattuva Mala and Natya Mala. Nattuva Mala is of two types- the Puja dance performed on the Balipitha in the temple and the Kalika dance performed in a Kalyana Mandapam. Natya Mala is of three kinds-ritual dance for gods, Kalika dance for intellectuals and Bhagavatam for common place.

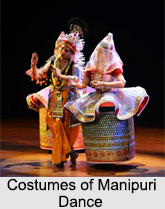

Costumes and Jewellery of Kuchipudi Dancers

Kuchipudi dance has now gained immense popularity because of its lilting music and graceful and flowing movements and vibrant stage presentation. Costumes of Kuchipudi dance look similar to Bharatnatyam costumes. The important characters have different make up and the female characters wear ornaments and jewellery such as Rakudi (head ornament), Chandra Vanki (arm ornament), Adda Bhasa and Kasina Sara (neck ornament) and a long plait decorated with flowers and jewellery. Ornaments worn by the artists are generally made of a lightweight wood called Boorugu.

Music in Kuchipudi Dance

Kuchipudi dance is accompanied by Carnatic Music. Cymbals, Mridangam, Violin, Thamburi and Flute are generally used in Kuchipudi dance. The Kuchipudi performance is led by a conductor (chief musician) called the Sutradhara or Nattuvanar, who typically keeps the beat using cymbals and also recites the musical syllables. The chief musician may also sing out the story or spiritual message, which is being enacted by the dance. Sometimes a separate vocalist takes this part. Kuchipudi orchestra consists of a drummer (Mridangam), a clarinetist and a violinist; it depends on the legend performing on the stage. A flutist is often seen to accompany the music.

Kuchipudi Dancers of India

Sidhendra Yogi championed the cause of redefining the Kuchipudi dance form. Kuchipudi was enriched by the advent of the female dancers. Renowned gurus like Vedantam Lakshminarayana, Chinta Krishnamurthy, and Tadepalli Perayya broadened the horizons of the dance form. Lakshmi Narayan Shastri and Chinta Krishnamurthy excelled in roles like Satyabhama in Bhamakalapam. Dr. Vempati Chinna Satyam, Yamini Krishnamurthy and Swapnasundari are some of the most renowned