About Yakshagana

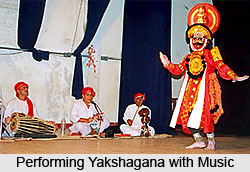

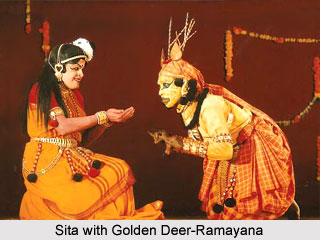

Yakshagana has been embedded in the history and culture of Karnataka for the past thousand years. This is a classical folk art, which has its roots in the mythologies and holy texts. Literally Yakshagana means songs of the Yakshas. According to Hindu mythology Yakshas are demi gods and the attendants of Kubera. In this dance drama the performers wear specific kinds of costumes and play several roles directly lifted from Holy Scriptures. In Indian dance forms costumes and make up play an important part. Intense make up and bright costumes makes the performances more interesting to watch out for. Traditionally Yakshagana was performed at night. Uttara Kannada, Shimoga, Udupi, Dakshina Kannada are some of the places in Karnataka where this form of performing arts is quite popular.

Yakshagana has been embedded in the history and culture of Karnataka for the past thousand years. This is a classical folk art, which has its roots in the mythologies and holy texts. Literally Yakshagana means songs of the Yakshas. According to Hindu mythology Yakshas are demi gods and the attendants of Kubera. In this dance drama the performers wear specific kinds of costumes and play several roles directly lifted from Holy Scriptures. In Indian dance forms costumes and make up play an important part. Intense make up and bright costumes makes the performances more interesting to watch out for. Traditionally Yakshagana was performed at night. Uttara Kannada, Shimoga, Udupi, Dakshina Kannada are some of the places in Karnataka where this form of performing arts is quite popular.

As the performance commences one would first come across Himmela or the background musicians. They are essential to every opera or dance drama. Then there is the Mummela or the dance troupe. These are the performers who will enact tales form the ancient culture and portray them to the audience. In earlier times such art forms were successful in educating the masses with the tales from holy books. They worked as fables with a moral ending. Yakshagana, thus, served a dual purpose of education and entertainment. Even in the contemporary Indian society they serve similar purpose. The difference is that they are now performed in theatres with few people interested to watch this dance form.

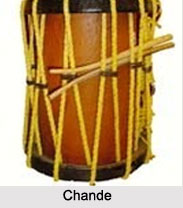

Yakshagana comprise of Bhagwata or the singer and percussion instruments, such as, Maddale, Mrudange, Harmonium and Chande (drums). The music used in Yakshagana is heavily drawn from folk music. The performance begins way before the actors get themselves on stage. Yakshagana generally commences during twilight with heavy beating of the drums. These are fixed compositions known as called Abbara or Peetike. This instrumental performance continues for an hour before the audience could see the actors on the stage. As the actors enter the stage one would find them in vibrant attires and heavy make up. Each character will have a different set of costume and make up. For instance the entire get-up of a king will be completely different from that of another character. For art lovers Yakshagana is a treat to watch.

There is a narrator who would help the audience to comprehend the story and other developments. He sings pre-composed dialogues with the help from background musicians. On stage the actors` dance to the tunes of the traditional folk music portraying whatever is conveyed by the song. The entire is narrated in this way. The dance drama of Karnataka is improvised from time to time depending on the capability of the actor. The stage where Yakshagana is performed is rectangular in shape built with four wooden poles. These poles are installed on four corners and then covered by palm leaves. The greenroom is called the chowki. The audience is supposed to sit on the three sides of the stage. For the purpose of comic relief there is the Vidushaka or the jester. This role too is played by the narrator.

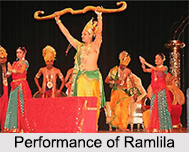

Although it is difficult to point out the exact origin of this art form it is at times thought to originate from the Bhakti Movement (Vaishnavism). This movement popularized religion through tales from epics in a simple form. Yakshagana is supposed to originate from here. This dance drama was popular by the time of a renowned Yakshagana poet Parthisubba. He rewrote Ramayana in this form of art. It is believed that he was the Bhagawata himself and established a dance group for the performance. He is also presumed to be the founder of Tenkuthittu of the art.

The first Yakshgana play was in Telugu & was written in the 16th century by Peda Kempa Gaudan and was called as Ganga Gauri Vilasam. Then came the renaissance period, followed by the 17th century, which was the time when the Yakshgana form developed in Karnataka, Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu. From the 15th century, in Andhra Pradesh, this folk art is performed both as a narrative song and as a dance drama. The form was also related to the Prabandha natak, which originated in a slightly later period. However, Yakshgana as a theatrical form regained popularity only in the 18th century. Till that time the written plays were created but mainly as scripts for presentations. Yakshgana emerged as a full-fledged theatre form in south Kannada at a time of great political unrest and social disturbances.

Yakshagana is widely performed in the districts of Dakshina Kannada, Uttara Kannada, Dharwad, Mysore and Hassan. Based Yakshagana can be classified into `Mudalapaya` (the custom of the East) and `Paduvalapaya` (the custom of the West). Mudalapaya is widely practiced in places like Tumkur, Bangalore, Kolar, Mandya, Mysore, Hassan,

Chitradurga, Bellary, Dharwad, Bijapur, Gulbarga, Raichur, Bidar and Belgaum. Paduvalapaya is well known in Karki, Keladi, Ikkeri, Sagar, Kolluru, Maranakatt, Sankuru, Coondapur, Kotesvara, Kota, Udupi, Dharmasthala, Mangalore, Brahmavara, Suratkal and Saligrama.

Chitradurga, Bellary, Dharwad, Bijapur, Gulbarga, Raichur, Bidar and Belgaum. Paduvalapaya is well known in Karki, Keladi, Ikkeri, Sagar, Kolluru, Maranakatt, Sankuru, Coondapur, Kotesvara, Kota, Udupi, Dharmasthala, Mangalore, Brahmavara, Suratkal and Saligrama.

The unique feature of Yakshagana is that the female roles are portrayed by male actors. They dress up in female attires to enact the roles of Yakshagana rakshasas. Traditionally folklores were adapted into performances as these were popular amongst the masses. Hence the work of spreading a message became easier. The tradition still continues today.

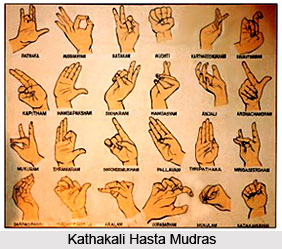

The original form of Yakshgana involves the use of recitative modes of poetry, melodies of music, rhythm and dance techniques, colourful costumes and graceful make up. It distinctly differs in many ways from the norms of the Sanskrit stage, as it does not contain a highly elaborate language of hand and eye-gestures, but it is closely related to developments in literature in the adjoining states of Andhra Pradesh and Tamil Nadu and has some affinities to literary forms.

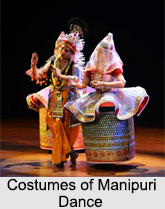

Costumes and Make-up of Yakshagana

Costumes and make-up of Yakshagana form an essential part of the folk theatre of Karnataka. Yaksagana artist is himself an adept in make-up and costume; he can use these elements expertly so as to bring out the innate character of the role he is portraying. The leading role of the performance is called Bannada Vesha or, literally, the character in colour. The name is a worthy compliment to the imposing make-up and gorgeous costumes of the role. The artist playing the Bannada Vesha spends in the normal course, four to five busy hours in making up and getting into his imposing garb. Make-up is a specialised art with Yakshagana and Kathakali and is the mainstay in recreating the atmosphere in which the Superman revelled. It is the imposing make-up and costumes that recreate the Superman on the stage and drive the audience in to a dreamland. The diffused dim light of the oil lamp called Panju or Deevatige and the great distance between the last spectator and the artist were obviously the considerations that conditioned the art of make-up in Yakshagana in the olden days; and further, the costumes were to be convenient for the vigorous dancing performed almost at every stage of the performance.

Costumes and make-up of Yakshagana form an essential part of the folk theatre of Karnataka. Yaksagana artist is himself an adept in make-up and costume; he can use these elements expertly so as to bring out the innate character of the role he is portraying. The leading role of the performance is called Bannada Vesha or, literally, the character in colour. The name is a worthy compliment to the imposing make-up and gorgeous costumes of the role. The artist playing the Bannada Vesha spends in the normal course, four to five busy hours in making up and getting into his imposing garb. Make-up is a specialised art with Yakshagana and Kathakali and is the mainstay in recreating the atmosphere in which the Superman revelled. It is the imposing make-up and costumes that recreate the Superman on the stage and drive the audience in to a dreamland. The diffused dim light of the oil lamp called Panju or Deevatige and the great distance between the last spectator and the artist were obviously the considerations that conditioned the art of make-up in Yakshagana in the olden days; and further, the costumes were to be convenient for the vigorous dancing performed almost at every stage of the performance.

Costumes of Yakshagana

Over the Kavacha, the tight upper banian and Challana, the tight trousers, every performer wears a full sleeved upper garment usually in green or red, and a veeragacche (hero`s girdle, a way of wearing the dhoti). If the role is of Yama - the God of Death, Narasinha, the great human with lion`s head or that of a demon, the girth of the character will be increased three fold with the help of thick sheets of cloth or sarees tied round the body. Loose garments, in appropriate colours to reveal the innate quality of the character - dark for the demon and reddish brown for kings, gods and chiefs (Maha Nayakas) are worn over and then come up the waist coat, embroidered with pieces of glass. The ornaments used are: bead necklaces and garlands, patti, koralahara, and sage around the neck, Bhujakeerti for the elbow, Tola pavada for the wrist, gold plates for the arms, crown for the head with Karnapatra (wings attached to the crown), Kennappo for the ear, Dagale the flowing piece of embroidered cloth falling in front from the waist, and jingles around the ankles. There are significant head-dresses and crowns with pronounced differences in shape and size. The most prominent crowns are Battalu Kireeta with a great halo, worn by royal characters like Dasaratha and Dharmaraja, Pombe Kireeta worn by characters like Lord Rama and Arjuna, Rakkasi Kireeta with peacock feathers worn by demons like Shurpanakhi and Hanumanthana Kireeta for Hanuman. A circular halo of the headdress made of white and black cloth decorated with silver lace tape and peacock feathers is called Sirimudi and is worn by characters like Lord Krishna and Abhimanyu. Sirimudi is in the shape of the human heart and is made in varying sizes and colours specifically for different characters. The size of the Sirimudi is symbolic of the stature of the character which wears it. After making up and wearing the prescribed costume, ornaments and the head dress, the Yakshagana artist gives a final touch by holding the relevant weapon - the mace, sword or the bow and arrow.

Over the Kavacha, the tight upper banian and Challana, the tight trousers, every performer wears a full sleeved upper garment usually in green or red, and a veeragacche (hero`s girdle, a way of wearing the dhoti). If the role is of Yama - the God of Death, Narasinha, the great human with lion`s head or that of a demon, the girth of the character will be increased three fold with the help of thick sheets of cloth or sarees tied round the body. Loose garments, in appropriate colours to reveal the innate quality of the character - dark for the demon and reddish brown for kings, gods and chiefs (Maha Nayakas) are worn over and then come up the waist coat, embroidered with pieces of glass. The ornaments used are: bead necklaces and garlands, patti, koralahara, and sage around the neck, Bhujakeerti for the elbow, Tola pavada for the wrist, gold plates for the arms, crown for the head with Karnapatra (wings attached to the crown), Kennappo for the ear, Dagale the flowing piece of embroidered cloth falling in front from the waist, and jingles around the ankles. There are significant head-dresses and crowns with pronounced differences in shape and size. The most prominent crowns are Battalu Kireeta with a great halo, worn by royal characters like Dasaratha and Dharmaraja, Pombe Kireeta worn by characters like Lord Rama and Arjuna, Rakkasi Kireeta with peacock feathers worn by demons like Shurpanakhi and Hanumanthana Kireeta for Hanuman. A circular halo of the headdress made of white and black cloth decorated with silver lace tape and peacock feathers is called Sirimudi and is worn by characters like Lord Krishna and Abhimanyu. Sirimudi is in the shape of the human heart and is made in varying sizes and colours specifically for different characters. The size of the Sirimudi is symbolic of the stature of the character which wears it. After making up and wearing the prescribed costume, ornaments and the head dress, the Yakshagana artist gives a final touch by holding the relevant weapon - the mace, sword or the bow and arrow.

Music and Instrument used in Yakshagana

Music and instruments used in Yakshagana helps to enhance the art in a major way. This is a theatre form where music and dance forms an integral part. Dance, the race-mode of the people of Karnataka is an inevitable aspect of Yakshagana, and is the most effective medium for rousing the sentiment of Raudra and Adbhuta.

Music and instruments used in Yakshagana helps to enhance the art in a major way. This is a theatre form where music and dance forms an integral part. Dance, the race-mode of the people of Karnataka is an inevitable aspect of Yakshagana, and is the most effective medium for rousing the sentiment of Raudra and Adbhuta.

History of Yakshagana

Yakshagana in its present appearance is believed to have been powerfully influenced by the Vaishnava Bhakti society. Yakshagana was first introduced in Udupi by Madhvacharya`s follower Narahari Tirtha. Narahari Tirtha was the minister in the Kalinga Kingdom. He also was the initiator of Kuchipudi. The first written data regarding Yakshagana is found on writing at the Lakshminarayana Temple in Kurugodu, Somasamudra, Bellary District. Yakshagana was an established performance art form by the time of the noted Yakshagana poet, Parthi Subba. The Yakshagana form of today is the result of a slow development, drawing its elements from ritual theatre, temple arts, secular arts (such as Bahurupi), royal courts of the past, and the artists` imaginations-all interwoven over a period of numerous hundred years.

In the 19th century, Yakshagana began to move away from the severe conventional forms. Yakshagana defies simple arrangement into categories such as folk, classical or rural. It can be included in each or all of these, depending upon the rules used for sorting. It is more varied and dynamic than most dance forms. Yakshagana can, though, be classified as one of many traditional dance forms.

In the 19th century, Yakshagana began to move away from the severe conventional forms. Yakshagana defies simple arrangement into categories such as folk, classical or rural. It can be included in each or all of these, depending upon the rules used for sorting. It is more varied and dynamic than most dance forms. Yakshagana can, though, be classified as one of many traditional dance forms.

Music and Instrument used in Yakshagana

Yakshagana lays particular emphasis on its percussion instruments like Maddale, Mridanga and Chande. Mridanga accompanies the Bhagavata in all his singing while Maddale and Chande are usually employed only in dramatic moments of tension. Chande, the most vital instrument of Yakshagana is a high-pitched drum, beaten with two thin sticks. Chande is the mainstay of Yakshagana in developing the sentiments of Roudra and Adbhuta. The rise and fall in the tempo of Chande, accompanied by Tala and Chakratala (bigger pair of cymbals) brings about the rise and fall in the emotional intensity of the performer and the battle becomes tense and thrilling. It is true that the cymbal is replaced by the gong and Pungi by the harmonium but there is no near about instrument to replace Chande. Chande remains the life sound of Yakshagana. The beat instruments in Yakshagana are the chande, maddale and a Yakshagana tala (bell).

Taala: Yakshagana bells or cymbals are a pair off finger bells made of a particular alloy. They are made to fit the tone of the bhagawatha`s voice. Singers carry more than one set, as finger bells are accessible in diverse keys, thus enabling them to sing in diverse pitches. They assist, produce and guide the background music in Yakshagana.

Maddale: The maddale is a percussion instrument and beside with the chande, it is the prime rhythmic addition in the Yakshagana ensemble.

Performance of Yakshagana

Performance of Yakshagana, in its final form, takes place in open air. On the evening of the performance Chande is beaten to convey the news and to invite the neighbouring villages. The sound of Chande, sharp and penetrating, easily reaches a village of even six to eight miles away if the wind is favourable. On the evening people assemble near and about the platform, generally in front of the village temple. The platform is about 16 feet square with bamboo poles fixed at the four corners. The top is covered by a mat made of palm leaves and the entire arena is decorated with flowers, mango leaves and also young plantain-trees tied to the poles on either side in the traditional way. On the three sides of the platform sit the audience spreading their own mats, while to the rear of the platform the Bhagavata (in plain clothes) with cymbals or gong in hand takes his place with his accompanists: the players of Maddale or Mridanga, Chande and Pungi or Mukha Veena - the drone. With this, the stage is set for the show.

Performance of Yakshagana, in its final form, takes place in open air. On the evening of the performance Chande is beaten to convey the news and to invite the neighbouring villages. The sound of Chande, sharp and penetrating, easily reaches a village of even six to eight miles away if the wind is favourable. On the evening people assemble near and about the platform, generally in front of the village temple. The platform is about 16 feet square with bamboo poles fixed at the four corners. The top is covered by a mat made of palm leaves and the entire arena is decorated with flowers, mango leaves and also young plantain-trees tied to the poles on either side in the traditional way. On the three sides of the platform sit the audience spreading their own mats, while to the rear of the platform the Bhagavata (in plain clothes) with cymbals or gong in hand takes his place with his accompanists: the players of Maddale or Mridanga, Chande and Pungi or Mukha Veena - the drone. With this, the stage is set for the show.

Elements of Yakshagana

The Yakshagana performance of the coastal tract opens with prayers (Nandi) to Gods Ganapati and Subrahmanya, sung by the Bhagavata. The jester Kodangi then enters the stage in a queer costume doing an odd dance and singing a song. Two players in female attire called Nitya Vesha then appear on the stage to sing and dance. This long series of several songs, dances and humorous talk provided by the minor roles, called Tundu Vesha, engages and amuses the audience and alerts their attention to the main show. Bhagavata sings again to signal the entrance of the chief characters of the performance. From behind the curtain held at the ends by two persons, gradually emerge the dressed up participants one by one until at last the most important character called Pundu Vesha or Bannada Vesha appears. Then in a row, they stand together to make a bow to the audience. It is a sight of real splendour and this completes Poorvaranga (preliminary formalities). Then the characters recede out of sight, leaving the Bhagavata and his accompanists on the platform. The Bhagavata then sings Prastavane or the prologue to the play chosen for the evening. As the tempo of his song rises accompanied by the fast beat of the cymbals, mridanga and chande, relevant characters enter to start the play proper. Every character dances into the stage, the pattern of dancing itself differing from one to the other in accordance with the spirit and sentiment for which the role stands.

Music of Yakshagana

After the end of the short dancing to the accompaniment of cymbals, mridanga and sometimes chande the character is interrogated by the Bhagavata who introduces him to the audience. In recent times however, the tradition is changed and the character himself - be it the king Rishi, Danava or Deva, at his first entrance introduces himself in dry prose, and then in a short speech acquaints the audience with the dramatic situation that has prompted him to appear. It is then the character assumes the role fully by interpreting in prose, dance and gesture, the various verses recited by the Bhagavata. When the verse refers to a particular character on the stage, that particular character alone keeps dancing in consonance with the mood of the verse. The climax is reached when the inevitable battle ensues between the hero and his foe. Accompanied by the severe beating of chande and mridanga at varying rhythms, the characters perform the war dance with all rustic vigour and grandeur, until the enemy is overpowered. Thus goes on the performance before the spell bound audience throughout the night and no one will be aware of the passing time. It was the custom, though now extinct, to see the Sun in the East and end the play after invoking his blessings.

Colours Used in Yakshagana

Yakshagana does not present two similarly made up and dressed characters unless warranted by a situation requiring two roles with identical innate qualities. Colours used for painting the face will be chosen with care. Gods are usually painted in reddish soft white, while roles like Yama, Bali and even Harischandra are painted in black. Lord Krishna is painted in a pleasant blue and the leading opposite role, the Bannada Vesha in black or pink. Originally, all the basic paints were made with the help of different indigenous colours called; Aradala, lngaleeka, Kadige and Balapa. It is over this foundation painting that careful working of the features of the character is made in red and white. The most imposing achievement of the Yakshagana artist could be seen in the make up of mythological characters like Narasimha, Ravana, Chandi and Yama. These characters will be able to create an illusion that they are wearing masks on their faces. It is so because the nose is uplifted with a lump of cotton, eyes are made to look three times their natural size, and a string of bordering white dots provides a decorated frame work (called Chutti) to the face and then, artificial canine teeth are fixed up.

Yakshagana does not present two similarly made up and dressed characters unless warranted by a situation requiring two roles with identical innate qualities. Colours used for painting the face will be chosen with care. Gods are usually painted in reddish soft white, while roles like Yama, Bali and even Harischandra are painted in black. Lord Krishna is painted in a pleasant blue and the leading opposite role, the Bannada Vesha in black or pink. Originally, all the basic paints were made with the help of different indigenous colours called; Aradala, lngaleeka, Kadige and Balapa. It is over this foundation painting that careful working of the features of the character is made in red and white. The most imposing achievement of the Yakshagana artist could be seen in the make up of mythological characters like Narasimha, Ravana, Chandi and Yama. These characters will be able to create an illusion that they are wearing masks on their faces. It is so because the nose is uplifted with a lump of cotton, eyes are made to look three times their natural size, and a string of bordering white dots provides a decorated frame work (called Chutti) to the face and then, artificial canine teeth are fixed up.

Actors of Yakshagana

Actors of Yaksagana have satisfied the tastes of the audiences. They are completely aware of the delicate touches of gestures and speed, helped by the make-up artists, the property man and even the prompter. The Yakshagana artist is at once a make-up expert, a dancer, and an effective actor with convincing declamatory powers. He, at the outset, should be strong physically; for the costumes of Yakshagana are cumbrous and heavy, its dances vigorous and entrancing. Above all, he should possess great presence of mind and cold commonsense. As in the case of the actor of the modern stage, the spoken word is not written down for the Yakshagana artist. The Bhagavata recites a verse and presents a theme to the artist to elaborate with his own words and acting. The spoken word is original, spontaneous and extempore. The prompter does not exist in the world of Yakshagana. It is this freedom of the artist and absence of any written dialogue that enlivens the performance and makes it new and sustaining every time. The prose interpretation demands that he should be alert every time though he may have played the same role in the same prabandha many times before. During a performance he lives in a state of real dramatic suspense as he would have no sure chance of knowing what his opponent would say next. This handicap is also the advantage of Yakshagana, for it changes the complexion of the dialogue and provides scope for alteration and improvement in characterisation. An artist would achieve the art of acting in Yakshagana only after careful observation and meticulous training for years, but the successful artists enjoyed a high status and honour in the coastal villages, and when they visited cities, they made a lasting impression on the urban audiences. They had a rare understanding of the secrets of acting and would compare well with any Indian or Western artist of the professional stage or screen.

Actors of Yaksagana have satisfied the tastes of the audiences. They are completely aware of the delicate touches of gestures and speed, helped by the make-up artists, the property man and even the prompter. The Yakshagana artist is at once a make-up expert, a dancer, and an effective actor with convincing declamatory powers. He, at the outset, should be strong physically; for the costumes of Yakshagana are cumbrous and heavy, its dances vigorous and entrancing. Above all, he should possess great presence of mind and cold commonsense. As in the case of the actor of the modern stage, the spoken word is not written down for the Yakshagana artist. The Bhagavata recites a verse and presents a theme to the artist to elaborate with his own words and acting. The spoken word is original, spontaneous and extempore. The prompter does not exist in the world of Yakshagana. It is this freedom of the artist and absence of any written dialogue that enlivens the performance and makes it new and sustaining every time. The prose interpretation demands that he should be alert every time though he may have played the same role in the same prabandha many times before. During a performance he lives in a state of real dramatic suspense as he would have no sure chance of knowing what his opponent would say next. This handicap is also the advantage of Yakshagana, for it changes the complexion of the dialogue and provides scope for alteration and improvement in characterisation. An artist would achieve the art of acting in Yakshagana only after careful observation and meticulous training for years, but the successful artists enjoyed a high status and honour in the coastal villages, and when they visited cities, they made a lasting impression on the urban audiences. They had a rare understanding of the secrets of acting and would compare well with any Indian or Western artist of the professional stage or screen.

Some of the masters in the art who are remembered even today are Kumbale Naranappa for portraying roles of humour, Kokkarane Ganapati for female roles, Kumbale Malinga for leading grand roles like Ravana and Balarama, and Upparahalli Shesha playing sublime characters like Karna. The legacy of this glorious art is ably borne today by experts like Keremane Sivarama Hegde, Karki Paramayya, Murur Devara Hegde, Brahma vara Veerabhadra and others in North Canara (Badagu tittu), and K. Vittala Sastri, Narayana Bhatta, Dejasetti, Haladi Rama and others in South Canara. When a performance of K. Shivarama Hegade or K. Vittal Sastri is witnessed, one feels that Yakshagana, in spite of the ravages of time and various pseudo-modern influences, has yet retained the rich traditions of Karnataka and if the art is supported, it would undoubtedly see brighter days.

Schools of Yakshagana

The coastal region in the west, extending from Goa to the border of Malabar has been divided into two parts, according to the differences in the technique of portrayal of Yakshagana. The Yakshagana of the northern region is called the Badagu tittu while that of the southern region is known as Tenku tittu. Udipi is the demarcating taluka. The Bhagavata of Badagu tittu uses a pair of cymbals (tala) while his counterpart in Tenku tittu uses the Gong (Jugate Kolu); the Mridanga of the North is longer and narrower at the ends giving sharp notes at a high pitch while in the South, the Mridanga has a greater diameter, giving the base notes of Kala and Mandara with sounds of Jhankar and Dhinkar; Chande in the south is used with better proficiency as an accompaniment for rousing even a delicate sentiment like Srngara and subtle dances as lasya and the reason for this superior exploitation of this powerful percussion instrument in the south is perhaps due to the better efficiency of the southerners in making this instrument. While the performance in the North pays greater attention to acting (abhinaya), the southern style has specialised in the art and technique of dancing. The Bhagavata of Tenku tittu is a lone singer, while in the north the Bhagavata is invariably accompanied by the performing artist also. While the northern Bhagavata stops singing with the beating of the cymbal, in the south, the Gong (Jagate Kolu) continues in three rounds even after the recitation of the Bhagavata stops, in order to give finesse to the dance of the character.

Finally, the make-up and costumes of the southern style is better in details and more imposing owing to the influence of the methods of Kathakali. These differences in the performances of Badagu tittu and Tenku tittu are obviously due to the local and regional influences as well as contacts; but the source and purpose of the performances remain the same and they produce almost the same unity of impression.

Prasanga Yakshagana is an open air play, and it cannot be performed during the monsoons, when, for four months in the year, heavy rains drench the coastal belt. In the absence of a full dress performance of Yakshagana in the open air, the coastal region has evolved an alternative method in what is called Prasanga or Tola Maddale, an indoor entertainment, closely following the methods laid down by Yakshagana. Prasanga is a virtual Yakshagana performance without the latter`s make-up, costumes and dances. In the presence of an audience assembled in a spacious hall, the Bhagavata sits in the centre with his accompaniments, and the artists (Arthadharias they are called in contrast with Vesadhari of Yakshagana) sit in front of him in two rows, each opposite to the other. The Bhagavata selects a particular Prasanga, sings the invocation and recites verses as in Yakshagana. The verses are interpreted by the artists each of whom assumes a role in the play, though he is not made up, nor costumed for it. Still, the illusion is created, for the participants talk with all the vigour, bearing and understanding of the roles they portray. The individual entity of the participant recedes into the background and the mythological heroes rise up before the mental eye and the audience enjoy the performance immensely, for after all, the physical eye beholds much less than the mental.

The Prasanga concentrates on the literary and emotional exposition of a theme. Compositions like Krishna Sandhana and Angada Sandhana, which provide greater scope for literary exposition and imaginative interpretation, are usually selected. The Prasanga is an evidence to show that tense dramatic situations and atmosphere could be created without dance or even costumes. What the Pauranik, the Kirtanakara and the Pathaka did single handed is done more ably by a team of learned artists here. The Prasanga has more dramatic tension in it than the performance of the Puranika or Kirtanakara; but still, it cannot be a Nataka in the correct sense of the word because of the absence of settings, dance, make-up and costumes. It is not improbable however, that it is the middle step between the pravachanakara on the one hand and the full-fledged Yaksanataka on the other in the evolution of the Kannada theatre.

Themes of Yakshagana

Themes of Yakshagana mainly deal with the mythological superhuman personalities, gods, demons and dream lands. Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata have provided suitable themes in abundance for Yakshagana. Moreover, they maintain a continuity of the Vedic influence by simplifying into didactic stories, the lofty tenets and philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanisads. Instruction with entertainment made a lasting impression on the rural audiences and thus, the lessons of the classics were inculcated. It is in this sense that Yakshagana remained the Night School for the masses, breathing the everlasting spirit of classical Sanskrit literature.

Themes of Yakshagana mainly deal with the mythological superhuman personalities, gods, demons and dream lands. Ramayana, Mahabharata and Bhagavata have provided suitable themes in abundance for Yakshagana. Moreover, they maintain a continuity of the Vedic influence by simplifying into didactic stories, the lofty tenets and philosophical teachings of the Vedas and Upanisads. Instruction with entertainment made a lasting impression on the rural audiences and thus, the lessons of the classics were inculcated. It is in this sense that Yakshagana remained the Night School for the masses, breathing the everlasting spirit of classical Sanskrit literature.

In selecting the theme for his Yakshagana Prabandha, the composer pays particular attention to the time-honoured sentiments of Veera and Raudra. He also provides scope for exploiting war dances. Thus, one can find that all the important battles mentioned in Indian epics are brought on the Yakshagana stage and prominent among them are Lord Krishna- Arjuna Kalaga, Babruvahana Kalaga, Hansadhvaja Kalaga, Karndrjuna Kalaga and others. Even if the Yakshagana Prabandha is about a marriage (Parinaya) or diplomatic dealing (Sandhana), there is perhaps no prasanga without a battle (Kalaga) in it. The title Girija Kalyana suggests a romantic theme, but it opens with the destruction of Daksa - Yajna by Lord Shiva and ends with the battle between the demon Taraka and Subrahamanya, the war God and son of Shiva. Thus with a due emphasis placed on battles, Yakshagana, like Kathakali, is a Tandava Prakara, a variant of the vigorous war-dance of Shiva. Lasya, the delicate dance-pattern, also finds its place but only too occasionally, as in Bhishma Parva, when three princesses softly dance with appropriate gesture to portray their bathing in the Ganga river, or as in Ravana Digvijaya when Ravana with his symbolic dance, washes his feet, hands and face before worshipping the Sivalinga. But the very life of Yakshagana is valour and power, its dominant sentiments, Veera and Raudra which ideally befit a Tandava Prakara.

Only recently, themes are drawn from Indian history and even here, due consideration is given to providing sufficient scope for battle dances. One of the representative prabandhas is Rana Rajasinha, composed by Sri K. P. Venkappa Setti. Social themes in Kannada theatre have not made their appearance on the Yakshagana stage, for the obvious reason that anything dealing with the ordinary human being would lack sustenance with the rural audience. The folk people could derive lofty morals only from the super-human characters.