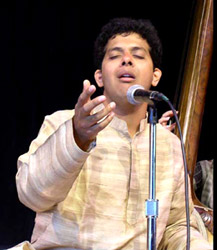

About Thumri

Thumri, a captivating vocal genre in Indian music, derives its name from the Hindi verb "thumuknaa," meaning "to walk with a dancing gait in such a way that the ankle-bells tinkle." This delightful form of music is intricately connected with dance, dramatic gestures, mild eroticism, evocative love poetry, and folk songs, particularly hailing from Uttar Pradesh. While Thumri exhibits regional variations, it is predominantly characterized by sensuality and a flexible approach to raga.

Thumri, a captivating vocal genre in Indian music, derives its name from the Hindi verb "thumuknaa," meaning "to walk with a dancing gait in such a way that the ankle-bells tinkle." This delightful form of music is intricately connected with dance, dramatic gestures, mild eroticism, evocative love poetry, and folk songs, particularly hailing from Uttar Pradesh. While Thumri exhibits regional variations, it is predominantly characterized by sensuality and a flexible approach to raga.

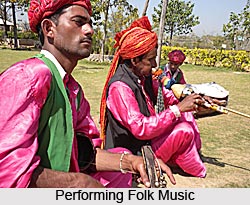

Thumri is not only confined to its own form but also serves as a generic name for several other lighter forms, including Dadra, Hori, Kajari, Sawani, Jhoola, and Chaiti. Each of these forms possesses its own unique structure and content, either lyrical or musical, often drawing inspiration from folk literature and music.

Significance of Thumri in Indian Classical Music

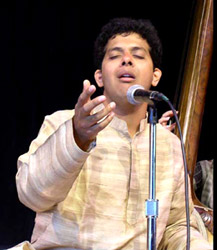

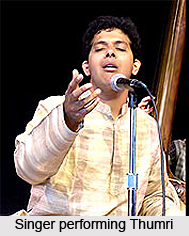

As the most important "light classical" genre of North Indian Classical music, Thumri holds a prominent position in various performance contexts. It finds expression in dance, vocal concert stages, and instrumental performances alike. Thumri is labeled as light classical due to several factors. Firstly, the melodies are not always composed in a strict Raaga, and they may even break the rules governing their rendition. Additionally, simpler talas and lighter raagas are often employed in Thumri. The absence of alap-type improvisation, which is considered the true test of musicianship, further contributes to its classification as light classical.

Moreover, traditional Thumri performances are accompanied by a harmonium, which, although adding to the charm, restricts melodic flexibility with its fixed pitches. Despite these distinctions, Thumri remains an enjoyable and soothing form of music, often serving as a delightful conclusion to vocal or instrumental concerts.

Romantic Essence of Thumri

Thumri is distinguished by its romantic and devotional lyrical content, predominantly sung in the Uttar Pradesh dialects of Hindi known as Awadhi and Braj Bhasha. The essence of Thumri lies in its ability to evoke emotions through its expressive and poetic verses. While some compositions refer to Lord Krishna and his amorous escapades, others focus on the experiences of lovers, showcasing the various stages of love, including unison and separation.

Text and Structure of Thumri

Thumri emphasizes the importance of the text, with clear pronunciation of each word and the heartfelt expression of the underlying emotions. This distinguishes Thumri from Khayal, another vocal genre in Indian classical music.

A Thumri composition consists of a sthai (main phrase) and one or more antaras (additional phrases) with room for improvisation. While some Thumri compositions contain additional text set to the same antara melody, others comprise only the sthai and antara. Gradually, as the performance progresses, the improvisation on the sthai text intensifies, exploring the middle and upper registers. This segment of the performance resembles the medium-speed khayal style. The antara is introduced when the upper register has already been explored in the improvisation, and it is initially presented partially, akin to a Khayal antara.

A distinct feature of Thumri performances is the inclusion of a section where the singing momentarily ceases, allowing the accompanying harmonium to take the melodic lead. This section, known as "laggi," highlights the virtuosity of the tabla player. Following the laggi, the singing resumes at the same tempo as before, typically with a second antara. The performance concludes with a return to the sthai and a final rendition of the main verse. Unlike the accelerating pace found in Khayal, Thumri maintains a relatively constant speed, providing a soothing and enjoyable musical experience.

Musical Elements in Thumri

Thumri is predominantly performed in "lighter" raagas such as Khamaj, Kafi, Tilang, Desh, Piloo, and Bhairavi. These raags offer greater flexibility and allow for emotive improvisations, enabling the artist to infuse the composition with rich nuances and variations.

The tala most frequently used for thumri are dipchandi (14 counts), jat (16 counts), Panjabi (16 counts), kaharva (8 counts), and dadra (6 counts). (Dadra tal is usually associated with a light classical genre that is also called dadra.) The 16-count talas jat and Panjabi have the same structural subdivisions as 16-count tintal, but the thekas with which they are drummed are very different, They can easily be distinguished in performance because the drummer keeps primarily to the theka.

Dipchandi of 14 counts is the same as jat tal, with one count removed in each half of the cycle (as indicated by the boxes in Example 7-10) so that the structure is 3 + 4 + 3 + 4. Bracketed strokes are played in one count. Since this tala has such a brief cycle, the singers go through several cycles of it before singing a cadence. The principle of keeping the text at the same points in the tala cycle and singing the full sthai phrase for cadences is kept more consistently than it is in khayal mukhra.

Language and Subject Matter in Thumri

Thumri compositions predominantly employ regional dialects of Hindi such as Awadhi, Bhojpuri, and Mirzapuri. However, Thumri also encompasses compositions in other languages, including Rajasthani, Marathi, and Bengali. The language of Thumri allows for a deep connection with the audience, as the lyrics often touch upon universal themes of love, longing, and the human experience. The verses of Thumri are filled with poetic imagery, metaphors, and vivid descriptions, enhancing the emotional impact of the performance. The lyrical content, combined with the melodic and rhythmic elements, creates a mesmerizing and immersive musical experience.

Evolution and Modern Interpretations in Thumri

Thumri has evolved over time, adapting to changing musical tastes and incorporating influences from various regional styles and artists. Traditionally, Thumri was performed in a semi-classical manner, passed down through oral tradition from one generation to another. However, with the advent of recorded music and the influence of popular culture, Thumri has also found its way into contemporary adaptations.

Contemporary artists have experimented with blending Thumri with other genres like jazz, fusion, and world music, resulting in innovative and eclectic interpretations. These interpretations have not only expanded the reach of Thumri but also brought it to the attention of a wider audience. While purists may argue about the authenticity of such experiments, they have undoubtedly contributed to the preservation and revitalization of Thumri as an art form.

Origin and Development of Thumri

The first traces of thumri go back to the 15th century, known to have likenesses with the dance form Kathak. Thumri is a lively musical style, evoking a sense of sensuality and amorousness, aimed at the subtle feelings of the heart. However, historical records speak of a different version of thumri during the 19th century, bearing similarity with khayal and depending on the elaboration of ragas. Many are of the view that thumri is a derivation of the madhura bhakti treatises of the Mathura-Vrindavan, concerning about the love intrigues of Krishna and Radha. Yet again, facts speak about Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh and his court musician, Sadiq Ali Khan, to have a significant hand in the evolving of this form of classical music. They are responsible for thumri being what it is today, due to their soulful compositions, along with several other musicians of their time. They had the power to assimilate their acquired legacy and render it masterfully.

The first traces of thumri go back to the 15th century, known to have likenesses with the dance form Kathak. Thumri is a lively musical style, evoking a sense of sensuality and amorousness, aimed at the subtle feelings of the heart. However, historical records speak of a different version of thumri during the 19th century, bearing similarity with khayal and depending on the elaboration of ragas. Many are of the view that thumri is a derivation of the madhura bhakti treatises of the Mathura-Vrindavan, concerning about the love intrigues of Krishna and Radha. Yet again, facts speak about Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh and his court musician, Sadiq Ali Khan, to have a significant hand in the evolving of this form of classical music. They are responsible for thumri being what it is today, due to their soulful compositions, along with several other musicians of their time. They had the power to assimilate their acquired legacy and render it masterfully.

Thumri, undoubtedly, is one of the most important forms of North Indian music after khayal. Its exact origins are not very clear, given that there are no historical references to such a form until the 15th century. Etymologically, the word thumri comes from thumka which means a nimble beat of the foot or walking with a dancing pace. The word connotes a form that is associated with choreographic movements, drama, all functioning under the canopy of romantic eroticism. The famous music treatise of the 15th century, Sangita Damodara, makes mention of a form called jhumri, which is `replete with love-sentiments, not bound by the constraints of prosodic rules, sweet as wine, the rhythm-oriented jhumri is sung by dancing females`.

Some hold that thumri has its genesis in the madhura bhakti compositions that originated in the Mathura-Vrindavan area, dealing with the amatory frolics of Krishna and Radha. As with most compositions that are labeled under the category of madhura bhakti, a poignant rendition was priviledged over adherence to formal rules, pertaining to raga development. Similarly, the folk melodies and evocative love songs associated with Braj (Agra-Mathura area) too are said to have been proto-forms of the modern thumri. In all, folk music, madhura bhakti, conventions, dance and dramatic traditions contributed to its origins. In fact, the thumri of the 19th century offered accompaniment to Kathak. In form, it bore a close resemblance to chhota khayal and was often set to spacious ragas like Yaman, Darbari and Malkauns. It was even customary for singers of the Benaras and Lucknow traditions, until some time back, to dance and even enact certain portions of the composition.

Though thumri is believed to have its roots in certain early genres of music, it is not until the middle of the 19th century that one notices it becoming enshrined as a form of classical music. The modern thumri is believed to be a `creation` of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh (1822-87) and his court musician, Sadiq Ali Khan. Wajid Ali Shah also composed outstanding thumris under the pen name, `Akhtar Piya` which are widely sung in repertoires. Yet historical evidence would have one to believe that Wajid Ali Shah and Sadiq Ali Khan along with several composers and musicians, who lived during the latter part of the 19th century, enhanced and amended the acquired legacy and gave it the discernible structure seen today. Importantly, Wajid Ali Shah`s role as a composer, practitioner, patron and connoisseur of thumri was to have a far-reaching impact on its development and maturation during the 19th century.

Though thumri is believed to have its roots in certain early genres of music, it is not until the middle of the 19th century that one notices it becoming enshrined as a form of classical music. The modern thumri is believed to be a `creation` of Nawab Wajid Ali Shah of Awadh (1822-87) and his court musician, Sadiq Ali Khan. Wajid Ali Shah also composed outstanding thumris under the pen name, `Akhtar Piya` which are widely sung in repertoires. Yet historical evidence would have one to believe that Wajid Ali Shah and Sadiq Ali Khan along with several composers and musicians, who lived during the latter part of the 19th century, enhanced and amended the acquired legacy and gave it the discernible structure seen today. Importantly, Wajid Ali Shah`s role as a composer, practitioner, patron and connoisseur of thumri was to have a far-reaching impact on its development and maturation during the 19th century.

A musician, dancer, actor, a poet of great talent and, above all, a patron of arts on a massive scale, Wajid Ali became more and more absorbed in the world of music, dance and drama at the cost of state affairs. He was, possibly, one of the most colourful aesthetes to adorn a throne. Wajid Ali was, going by certain historical accounts, a `misfit` as a ruler, given his exquisitely cultured and refined sensibilities. Soon enough, he became victim to the cunning intrigues of the British, who annexed the state of Awadh and pensioned him off to Kolkata in 1856. The wrenching thumri, Babul mora naihar chooto hi jae, in Bhairavi, is supposed to have been composed by Wajid Ali on the eve of his departure to Kolkata. It was his farewell oration to Lucknow - his song of farewell to that city of love and song and its haunting romantic ambience, which he loved above all other things. Sanad Piya of Rampur court and Kadar Piya, who lived in the 19th century, also composed a number of thumris known for their poetic delicacy and deep sentiment. These doyens were able to coalesce poetry and music, lyricism and expressivity, form and feeling in aesthetically pleasing ways to give one the form, as one understands it today.

Unlike the khayal, which pays meticulous attention to unfolding a raga, thumri restricts itself to expressing the countless hues of shringar by combining melody and words. The contours of a khayal are most definitely broader and fluid. Thus, a khayal singer is capable of encompassing and expressing a wide range of complex emotions. A thumri singer goes straight to the emotional core of a composition and evokes each yarn of amorous feeling, each strand of sensuous sentiment, with great discretion. Khayal aims at achieving poise and splendour; thumri is quicksilver in tone and ardently romantic in spirit. It needs a delicate heart, and a supple and soulful voice capable of expressing several shadings and colours of tones to bring out its beauty. To draw an analogy from the world of painting, khayal is closer, in form and spirit, to the unrestrained and energetic world of Renaissance masters like Michelangelo, Raphael and Titian - forcefully executed brush strokes are seen on a broad canvas; whereas thumri, with its affinity for finer points and shades of feeling, emotion and mood, is closer to the finely-detailed still-life paintings of the Dutch masters of the 17th century.

Styles of Thumri

Styles of thumri have developed gradually along the course of the development of the art. Thumri has had a rather long tradition and can be traced right back to the age of classical Sanskrit plays and later to the Vaishnava Bhakti cult and the rasa natya. However, the Thumri as it is known today received great patronage, currency and shape during the days of Wajid Ali Shah when he was the Nawab of Lucknow, from 1847 to 1856. Its present tradition is also linked with Kathak dance and Thumri continues to be an essential feature of the Kathak nirtya. Thumri also evolved as a mode of vocal music without any recourse to the visual, i.e., acting or abhinaya, and aiming its expression only through music and words.

Styles of thumri have developed gradually along the course of the development of the art. Thumri has had a rather long tradition and can be traced right back to the age of classical Sanskrit plays and later to the Vaishnava Bhakti cult and the rasa natya. However, the Thumri as it is known today received great patronage, currency and shape during the days of Wajid Ali Shah when he was the Nawab of Lucknow, from 1847 to 1856. Its present tradition is also linked with Kathak dance and Thumri continues to be an essential feature of the Kathak nirtya. Thumri also evolved as a mode of vocal music without any recourse to the visual, i.e., acting or abhinaya, and aiming its expression only through music and words.

The gharana creed and convention does not have as much of a hold on Thumri as it does on the Khayal. The reason for this is that the nuances of Thumri are not easy to copy and have a subjective character in mood-expression. The Thumri sings of the viraha of Radha or the gopi; it is the main theme, and the effect is sensuous, emotional charged and deep. As for its spiritual significance, it is prema-bhakti, of the prakrti (the transient female element or atma) towards the purusa (the eternal male element; paramatma; god).

Types of Thumri

There are different types of Thumri that are practiced and are in vogue.

Banaras Anga Thumri: It very much suited to the emotive aspects, interpreting the song, the phrases, the words, even projecting several sancari bhavas through vocal techniques, called kaku-prayoga and bola-banava. It requires a non-obtrusive theka in slow tempo in the main phase of the rendering. This style of thumri is similar to the bada khayal, since its bola-banava (mobilizing the words), kahan (utterance), phrasing and rumination is centered round raaga-anga and mixes the main raaga-anga harmoniously and effortlessly, with the song without sudden flights.

Punjab Anga Thumri: It is full of murkis and thrills and creates a special charm when it takes two adjacent notes, like two rsabhas or two gandharas and swift sallies in taans from the higher octave to the lower one. This is definitely a different tradition in notes but it is bound to get repetitive as it gets exhausted after a time. There are musicians today who try to combine these two styles, but it is not a regular feature as each style requires riyaz in a distinctive vocal technique.

Bandisa Thumri: This is the third pattern of thumri where the composition has high musical value. Here, the text is longer having a literary charm, and the composition may be in a raaga and the rendering restricted to it. Kathaks are better reputed to know this type of thumri. This third type is practiced less frequently nowadays. The reason for this appears to be the fact that bhajana, gita, pada and other such fare, called light music, offer nearly everything that a Bandisa Thumri may have to offer musically.

Bola Banao Thumri: It is known as artha-bhava. Artha means meaning and bhava means emotions. The bola-banao thumri is performed at a much slower tempo than the bandisa thumri. In the choreographic context, this form was appropriate for dance formats devoid of fast or intricate footwork. By the early twentieth-century, it stabilized at a rendition tempo approximately twice the beat-density of the contemporary bada khayal.

Thumri as such has now gained a better status in musical hierarchy and in the society during the last thirty years or so compared to what it enjoyed previously. Now nearly every chamber concert or music conference includes thuman in its fare, and nearly every vocalist or instrumentalist wishes to excel in classical as well as light classical both, and endeavors to charm the audience which is keen to listen to a variety of styles. In recent times, there is seen a revival of the jalsas (musical soirees) where thumris are punctuated with dadaras and, ghazals, even gitas and bhajanas. However it must be said here that in the company of other lighter forms, the thumri is in danger of losing its character and form.

Ragas in Thumri

The sixteen Ragas in Thumri are: Dhani, Tilang, Sivranjani, Bhairavi, Khamaja, Pilu, Ghara, Zilla, Kafi, Pahari, Manja Khamaja, Mand, Kausi-Dham, Sindhura, Jangula and Bihari. Thumri is a genre of semi-classical Indian music. It is romantic or devotional in nature. Its ragas are very flexible.

The two major ragas of thumri are Desa and Tilaka Kamodare found in the mainstream classical genres. Jhinjhoti and Bhairavi also belong to this category. They are minor ragas in the mainstream vocal genres. The melodic framework of the genre derives from a group of relatively undifferentiated modal entities, almost certainly of folk origin.

Most of these ragas have a relationship of tonal geometry and phrasing similarity especially Khamaja, Bhairavi and Kafi. Khamaja, Bhairavi and Kafi are three popular ragas of thumri. This makes it possible for a phrase from one raga to be sung in the other ragas in a different scale-base. It creates a reappearance of the melodic contours through the genre, making the genre more accessible and thereby contributing to its stylistic distinctiveness.

The manner in which melody is treated in Thumri reflects their coherence within well-defined melodic settings. Though there is grammar informality, the crossing of boundaries is judicious. Thumri cannot be rendered in a raga-malika manner.

The commonly used ragas in this genre are Pilu, Kafi, Khamaj, Gara, Tilak Kamod and Bhairavi. It is said that less weight ragas are used in Thumri. In form, it bore a close resemblance to chhota khayal and was often set to spacious ragas like Yaman, Darbari and Malkauns.

This article is a stub. You can enrich by adding more information to it. Send your Write Up to [email protected]

Tala in Thumri

Tala in Thumri is mostly based on the formal tinatala pattern. The nineteenth century bandisa thuman relied almost entirely on the formal tinatala. Thumri is a common genre of semi-classical Indian music. It became popular during the 19th century in the Lucknow court of nawab Wajid Ali Shah.

Tala in Thumri is mostly based on the formal tinatala pattern. The nineteenth century bandisa thuman relied almost entirely on the formal tinatala. Thumri is a common genre of semi-classical Indian music. It became popular during the 19th century in the Lucknow court of nawab Wajid Ali Shah.

Thumri is indeed a diversified form of classical music, with the incorporation of the brilliant combinations of bandishes of various ranges, taals and another innovative version of bandish, bol-banav in slow tempo (vilambit laya). The text of Thumri is romantic or devotional in nature, and usually revolves around a girl`s love for Krishna. Some bandisa thumans were rendered in "Punjabi tinatala." This version of folk origin was to later play a bigger role in the bola-banao thuman. The bandisa thuman was a genre for the medium to fast tempo, with an explicit rhythm. In its version, it also drew a lively interaction between the poetic-melodic and rhythmic elements. This equation between the different elements changed dramatically as the tempo of the bandisa thuman slowed down. The bola-banao thuman took over and drifted closer to folk genres. Rhythm was now downgraded to the back seat.

Drifting apart from the multiple nomenclatures and multiple versions, the bola-banao thuman primarily uses cancara or dipacandi of 14 beats in 3+4+3+4 subdivision, keherva of eight beats in 4+4 subdivision, dadra of six beats in 3+3 subdivision, and tmatala of 16 beats, rendered in a stylized, or probably folk manner. This account of tmatala is, presently known by several names like sitarakhani, addha, punjabi, and qawwali. This idiom is an asymmetrical and dented interpretation of the symmetrical [4+4+4+4] subdivision of the tola. The sitarakhani, addha, Punjabi, qawwali, generally played in medium tempo, interprets the 4-beat subdivision in the tala as an 8-beat subdivision, and renders it with percussion strokes falling on the 1st, 4th and 7th markers of the notionally 8-beat subdivisions. This interpretation of the tmatala brings its rhythmic experience remarkably close to the 14-beat dipacandi.

Amongst the talas used in the thuman genre, dadam of six beats poses a special problem because this happens also to be the name of a genre of vocal music belonging to the thumari family.

Thumri Singers

Thumri is the most important "light classical" genre of North Indian Classical music. It is performed in many contexts, from the sphere of dance, to the vocal concert stage, to performance on instruments. In eighteenth-nineteenth-century Thumri reached its zenith in Awadh. The evolution of Lucknow tradition is attributed to Prakashji who is considered as an exponent of the Rasa form. He had migrated from Allahabad and remained under patronage of Nawab Asafuddaula. Later Prakashji`s sons, Durga Prasad and Thakur Prasad became tutors of the next Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah. Durga Prasad had two sons, Kalkaji Maharaj and Binda Din Maharaj. His later son had introduced thumri to Kathak dance by composing thumris specifically as support for interpretative dance.

Thumri is the most important "light classical" genre of North Indian Classical music. It is performed in many contexts, from the sphere of dance, to the vocal concert stage, to performance on instruments. In eighteenth-nineteenth-century Thumri reached its zenith in Awadh. The evolution of Lucknow tradition is attributed to Prakashji who is considered as an exponent of the Rasa form. He had migrated from Allahabad and remained under patronage of Nawab Asafuddaula. Later Prakashji`s sons, Durga Prasad and Thakur Prasad became tutors of the next Nawab, Wajid Ali Shah. Durga Prasad had two sons, Kalkaji Maharaj and Binda Din Maharaj. His later son had introduced thumri to Kathak dance by composing thumris specifically as support for interpretative dance.

Wajid Ali Shah

Wajid Ali Shah played an important role in popularizing the kathaka-thumri renaissance. Under the guidance of Durga Prasad and Thakur Prasad, he became a formidable dancer. He was also trained by Sadiq Ali Khan and became a fine vocalist. He is credited with writing three volumes of song-texts for the thumri, dadra, khayal and sadra genres of vocal music. Wajid Ali wrote a Vaishnavite dance drama called "Indra Sabha" in Urdu, with songs in Braj bhasa. His thumri composition `babul mora naihara chuto jaye` is considered an immortal composition.

Sadiq Ali Khan

Sadiq Ali Khan born on 1800 was a vocalist who had descended from a lineage of qawwali singers. He was associated with the Khayal genre. Khan is credited with refining the bandisa thumri and laying the foundations of the bola banao thumri. Many talented musicians like Inayet Hussain Khan of Sahaswan gharana, Ramakrishna Vaze of Gwalior gharana and Bhaiyya Ganpat Rao became his disciples.

Bhaiyya Ganpat Rao

Bhaiyya Ganpat Rao of Gwalior was trained in dhrupad, khayal and the Rudra Veena. He greatly practiced the harmonium and the thumri genre. He studied thumri with Sadiq Ali Khan and Khurshid Ali Khan of Lucknow. He helped in shaping the incipient bola-banao thumri by performing it on the eminently unsuitable harmonium. Under his influence, the harmonium fast replaced the traditional sarangi as the standard melodic accompaniment for thumri. Under the pseudonym "Sughar Piya," he composed a large number of thumris, which became immensely popular. Some of the greatest thumri singers of his times were his students. Amongst them were great courtesans, Gauhar Jan, Jaddanbai, Malka Jan and male vocalists Mauzuddin Khan, Mir Irshad Ali and Babu Shyam Lai.

Jagdeep Mishra

Jagdeep Mishra of Varanasi played a similar pioneering role in the evolution of the bola-banao thumri. Mishra belonged to a family of hereditary Kathak exponents and is considered a co-founder of the Banaras bola-banao tradition.

Siddheshwari Devi

Siddheshwari Devi is also one of the outstanding semi-classical vocalists of her times. She had studied khayal and thumri with her aunt Rajeshwari Bai. The leisurely classicism of her thumri renditions brought them almost on par with the bada khayal.

Rasoolan Bai

Rasoolan Bai was a famous thumri singer. She had studied primarily with khayal vocalists, sarangi players and Kathak exponents. She was famous for her thumris, dadaras, and tappas. Her melodic range and imagination had reached great heights.

Begum Akhtar

Begum Ak]htar born in 1914 is another significant vocalist from Faizabad. She had studied Khayal with Wahid Khan, Ata Khan of Kirana Gharana, and with other Patiala maestros. She performed thumri, ghazal, dadara, and the allied folk genres. Her thumris were a blend of the Benares and Punjab styles. Her thumris were short, up to about ten minutes each. She is credited with the development of the ghazal. Akhtar enriched its melodic content enough to bring it almost on par with the bola-banao thumri.

Abdul Kareem Khan

Abdul Kareem Khan born on 1872 was the founder of the Kirana gharana of the khayala. He virtually redefined the thumri by taking the erotic, and partially the folk, out of the Benares bola-banao thumri, and replacing it with an intense poignancy and devotional fervor. He made the thumri respectable in the khayal world. The second and third generations of his lineage continued the dissemination of his style of thumri.

After Abdul Kareem Khan many other popular Thumri Singers emerged like Faiyyaz Khan of Agra Gharana, his son Sharafat Hussain, the brothers from Patiala, Bade Ghulam Ali Khan and Barkat Ali Khan. Besides Badi Motibai, Rasoolan Bai, Girija Devi, Pandit Channulal Mishra, Begum Akhtar, Shobha Gurtu, Noor Jehan, Cassius Khan and Prabha Atre were also popular thumri singers.

Other eminent khayal singers who had a flair for Thumri singing were Vilayat Hussain Khan of Agra, Mushtaq Hussain of Rampur-Sahaswan, Rehmat Khan of Gwalior and Kesarbai Kerkar of Jaipur-Atrauli.

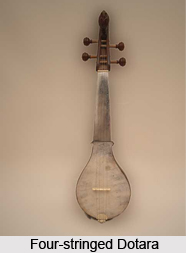

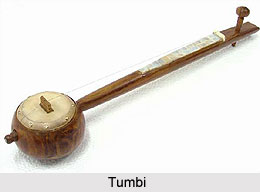

Influence of Thumri on Indian Musical Instruments

The thumri genre has had the most profound influence on the idiom of the sitar and the saroda, the two instruments that rose to prominence in eighteenth and nineteenth century Lucknow, the home of the kathak-thumri renaissance. The sitar inherited its original idiom from the rudra veena, the primary instrument of the medieval dhrupad genre. Ghulam Raza Khan, a late eighteenth century Lucknow sitarist, developed such an idiom by a direct and immensely successful transposition of the bandisa thumri composition format onto the stroke pattern of the sitara.

The thumri genre has had the most profound influence on the idiom of the sitar and the saroda, the two instruments that rose to prominence in eighteenth and nineteenth century Lucknow, the home of the kathak-thumri renaissance. The sitar inherited its original idiom from the rudra veena, the primary instrument of the medieval dhrupad genre. Ghulam Raza Khan, a late eighteenth century Lucknow sitarist, developed such an idiom by a direct and immensely successful transposition of the bandisa thumri composition format onto the stroke pattern of the sitara.

The saroda was an important part of the Lucknow court under Nawab Wajid Ali Shah. Saroda had inherited a bi-directional stroke pattern from the rababa. Along with the slow tempo of Masit Khani format, the sitar and the sarod came to adopt the medium-to-fast tempo of Raza Khani format as standard repertoire. Although both instruments have been popular in the twentieth century, the Masit Khani and Raza Khani formats remain, to this day, the mainstays of sitara and saroda music.

The sitara was greatly influenced by the thumri genre. It attained its highest level of sophistication in the hands of Ustad Enayet Khan`s son, Ustad Vilayat Khan. He has adapted compositions from both the thumari sub-genres and them popular across all movements. The totality of his "thumari experience" also gains a lot from his brilliant vocalization of bola-banao along with its rendition on the sitara.

The thumari genre has also influenced other major instrument i.e. sarangi. By the nineteenth century sarangi became the standard accompaniment to the thumari as well as the khayala. The sarangi player has been an important connection between the worlds of thumari and khayala.

Shehnai music has been inspired by the thumari genre. This has been possible for the towering influence of Ustad Bismillah Khan. He was born in Varanasi which is considered as the home of the bola-banao thumari. The sehnayi acquired a repertoire dominated by folk and regional music. When Bismillah Khan raised the sehnayi to the status of a concert instrument, he also made the dadra, kajan, caiti, and faguna songs of the Benares region an integral part of sehnayi repertoire.

The Bansuri has conceded a significant place to the thumri and other semi-classical genres in its list. This pattern is attributed to the phenomenal musicianship of two maestros, Pannalal Ghosh and Hariprasad Chaurasia. Ghosh tended to perform bola-banao thumaris more frequently in the traditional dipacandi while Chaurasia has an affinity for keherva, rupaka and dadara.

Thumri in Modern India

Thumri has been an integral part of Kathak dance. This genre claims about two vocalists of stature Girija Devi who was born on 1929 and Shobha Gurtu who was born on 1925. Both these singers were devoted to the practice of the Varanasi tradition of Thumri and its allied genres, such as dadra, caiti, kajan, and others.

Thumri has been an integral part of Kathak dance. This genre claims about two vocalists of stature Girija Devi who was born on 1929 and Shobha Gurtu who was born on 1925. Both these singers were devoted to the practice of the Varanasi tradition of Thumri and its allied genres, such as dadra, caiti, kajan, and others.

Amongst the leading khayal exponents, the notable performers of the bola-banao Thumari, are Pandit Bhimsen Joshi born on 1922, Ustad Niyaz Ahmed Khan born on 1928, Parveen Sultana born on1948 and Prabha Atre born on 1932. Other younger male vocalists, like Rashid Khan, Ulhas Kashalkar, and Ajoy Chakravarty perform Bandisa Thumris with great competence, distinguishing them astutely from the chota khayal.

It has been noticed that not more than one in twenty vocal music concerts in contemporary Hindustani music ends with either a Bandisa Thuman or a bola-banao thumri. Around the middle of the twentieth century, the thumris share of the tailpiece position was at least five times greater than it is today.

Two factors have predominantly influenced the emergence of thumri substitutes in the tailpiece position - the de-emphasis of the romantic element in the concert hall context, and emergence of western state of Maharashtra as the home of khayal vocalism.

Due to Maharashtra`s ascendancy over the Khayal platform, the tailpiece position has increasingly been taken up by classicist renderings of bhajans that have been composed by the major poets of the Bhakti Movement. It has also been affected by the folk devotional genres from Maharashtra such as abhangas and kirtanas, and semi-classical songs from the Marathi drama and theatre, called natya sangita. Most of these thumri-substitutes have few features of either the bola-banao or the Bandisa Thutnans. They fill a part of the aesthetic space earlier occupied by the thumri.

However, the aesthetic space the thumri occupied cannot disappear with the eclipse of the genre. The encroachment into this space began around the middle of the last century when the Varanasi bola-banao tradition was in full bloom, and originated from the classical as well as the light music ends. Thumri was also affected by the growth of ghazal with Begum Akhtar as its high priestess. Inspired by her music other notable singers like Jagjit Singh; Mehdi Hassan also substantially widened the scope of ghazal and made it popular among the people.