Introduction

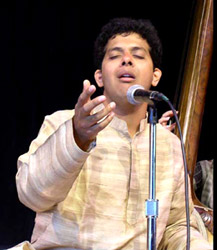

Raaga is the most important concept in Indian classical music. Raaga has been derived from the Sanskrit Language word `Ranja`, standing for an element that delights and enthralls the mind. Raaga is a combination of notes illustrated by melodic movements. There are numerous types of Raagas, like - Multani, Jaunpuri, Gaud, Sorath, Maand and Pahadi, Ahiri, Gurjari, Asavari, including several others. Raaga utilizes the entire range of the octave, starting with Aroha and ending in Avaroha, where the singer culminates the recital.

Raaga is the most important concept in Indian classical music. Raaga has been derived from the Sanskrit Language word `Ranja`, standing for an element that delights and enthralls the mind. Raaga is a combination of notes illustrated by melodic movements. There are numerous types of Raagas, like - Multani, Jaunpuri, Gaud, Sorath, Maand and Pahadi, Ahiri, Gurjari, Asavari, including several others. Raaga utilizes the entire range of the octave, starting with Aroha and ending in Avaroha, where the singer culminates the recital.

Structure of Raaga

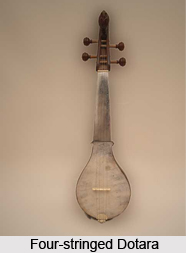

The various formations of scales become the basis of the Raaga. That is to say, the infinite permutations and combinations obtained by the arrangement of the seven Svars plus all the Srutis, provide the basis for the formation of innumerable tunes or melodies which are called the Raagas and Raaginis of Indian music.

Features of Raaga

There are certain essential features which characterize every Raaga. A Raaga must have at least five notes, and it cannot omit Sa and must also contain some form of ma or pa as well. A Raaga uses a certain selection of tones: ones that are omitted are termed "forbidden" and cannot be used without destroying the Raaga. There are many Raagas have strong tonal centers, called Vadi and Samvadi. For Gaur Sarang, for example, these are G and D respectively.

Typically, these two notes are a fourth or a fifth apart. The Vadi-Samvadi does not substitute for the importance of the tonal center Sa in a Raaga, and do not always function the same way for each rag. Certain moods are typically associated with each Raaga, and often a time of day or season of the year. Again, Gaur Sarang is an afternoon Raaga with the moods of peace and pathos. Prescribed melodic movements that often recur, like catch phrases, identify the Raaga. In Gaur Sarang one such phrase is G R m G. There can be precise use of timbres and tonal shading, heightened by the use of microtonal pitches that vary from one rag to another, lending particular character to the rag. Raga is a combination of sounds along with "Varnas". A "Raga" is particularly the different series of notes within the octave which forms the basis of all Indian Raagas. The source of Raaga is Thala. Similarly two notes of same denomination should not come one after another. Again in a Raaga notes `Pa` and `Ma` cannot be put together. A Raga should have Varnas that include "Aroha" and "Abaroha" and it must also have fixed "Vadi" and a "Samavadi" note.

Typically, these two notes are a fourth or a fifth apart. The Vadi-Samvadi does not substitute for the importance of the tonal center Sa in a Raaga, and do not always function the same way for each rag. Certain moods are typically associated with each Raaga, and often a time of day or season of the year. Again, Gaur Sarang is an afternoon Raaga with the moods of peace and pathos. Prescribed melodic movements that often recur, like catch phrases, identify the Raaga. In Gaur Sarang one such phrase is G R m G. There can be precise use of timbres and tonal shading, heightened by the use of microtonal pitches that vary from one rag to another, lending particular character to the rag. Raga is a combination of sounds along with "Varnas". A "Raga" is particularly the different series of notes within the octave which forms the basis of all Indian Raagas. The source of Raaga is Thala. Similarly two notes of same denomination should not come one after another. Again in a Raaga notes `Pa` and `Ma` cannot be put together. A Raga should have Varnas that include "Aroha" and "Abaroha" and it must also have fixed "Vadi" and a "Samavadi" note.

Raaga and Time

The Raagas are essentially time bound, and divisions are made with the kinds and exactly when to be sung. Since ancient ages, there is a firm belief that a Raaga must be performed at a fixed time or season, because it is assumed that every Raaga is harmonized with the natural disposition of each person.

The Raagas are generally governed by time and seasons. According to the division of the day and night, the Raagas have also been divided into groups, due to the sensations they emote when performed. The Raagas for the diurnal period are called Dinegeya or Suryamsa Raagas, whereas for the nocturnal are called Ratrigeya or the Chandramsa Raagas. And the sub-divisions are named as Sandhiprakash Raagas - the Raagas sung during the twilight, Pratah-Sandhi Raagas - the Raagas sung during the transitional period of night and morning. It is also stated that a day is divided into eight Praharas, or the quarters or watches, each lasting for three hours. And the Raagas that are sung are divided according to the importance of the notes in every one of them. The octave is further divided into Uttaranga and Poorvanga, denoting the upper and lower cases of the musical octave.

Development of Raaga in Indian Music

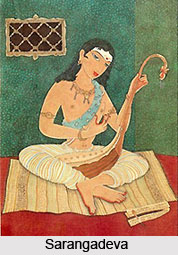

Development of Raaga in Indian Music has been the outcome of and been influenced by a number different factors. Raagas comprise one of the purest aspects of music, the non-referential part which existed even before Bharata wrote his treatise. Raaga should be examined from the point of conceptual expression of the lived style and philosophy of the enlightened community which experiences life in consonance with nature, other beings and other men who find through music their communication in the membership of the larger society.

Development of Raaga in Indian Music has been the outcome of and been influenced by a number different factors. Raagas comprise one of the purest aspects of music, the non-referential part which existed even before Bharata wrote his treatise. Raaga should be examined from the point of conceptual expression of the lived style and philosophy of the enlightened community which experiences life in consonance with nature, other beings and other men who find through music their communication in the membership of the larger society.

It has been observed by scholars of Indian Music that the manifestation of the Cosmic Being appears, from the point of view of men, to take place within three distinguished yet co-related orders. One is a successive order implying the same form of duration; the second is a matter of relative location implying the same form of space; and the third is an order of perception implying degrees of consciousness and therefore stages of manifestation." This envelopment of all the three orders (duration, space relative location of notes, and perception of raaga) could be found in this partial or perceptible universe- "channels through which to conduct our investigation into the extra sensorial world."

It is said that when a musician sings or performs a raaga, he has already prescribed for himself a path. He has a conception of raaga in his consciousness and engages himself in recreating the spirit through sensuous elements he has at his command. He accepts willingly all the parameters of raaga for reasons of his own sensibilities. In a way he is possessed by the raaga and consciously or subconsciously accepts the dictates of the raaga and the style. This dictation carries with it an entire thought and tradition behind the evolution of the raaga during the ages. Raaga is at once attributed to Divinity revealing its mystic powers. It is experienced as an aspect of divinity, and it is interconnected with other manifestations.

According to Hindu principles, all the aspects of the manifest would spring from similar principles. They have a common ancestry.

Raaga has lived through the Indian view of the cosmos, the Brahman, and has received the samskara all through and thus achieved the vitality to generate further sarhskaras as well. Considering the 2000-year old culture of raaga and the tree of raaga in an environment of its close co-life with other forms of arts, religion and Indian thought, the contour contents of the raaga as found at this end of the story, the present-day music, show vital signs of the culture we have lived through and of which we ourselves are the product.

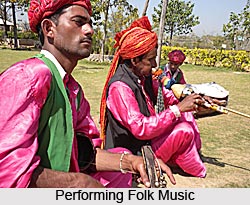

One of the strongest factors in the development of Raagas has been the impact of nature. The intimacy with nature is one of the strong features of our Vedic culture. This is reflected in Vedic literature. Our melodic music based on the simple and natural scale may appear to some to be primitive or ethnic, but it is a phenomenon of organic order. Indian musical scale has remained stable, as it is called a Natural scale. It is as ancient and as modern as the structure of our physical body. It has in itself inherent harmonic structure based on the laws of physics and acquired by the human apparatus of voice under the natural evolution. The pentatonic scales or modes, the origin of which is attributed to folk music, provide relation of the thoughtful in our music to the musical sub-structure in the community life.

This connection with nature is best seen in the philosophy of treating certain raagas more appropriate for certain seasons, and raagas linked to certain hours or periods (prahams) of day or night. When considered in the context of our age-old agricultural economy and festivals connected with the cycle of crops and seasons, the tunes good enough to make the total expression more meaningful and explicit flowered in the form of folk songs and recitals. These served, very suitably, to nourish and celebrate life. The cycle of seasons provided a cycle of events-rituals, resulting in associations and conventions. Along with the literary-religious component of music, the musical component received simultaneously the same approach, words and tunes and ragas in service of gods of which they were the manifestation.

In sum, the mode of music received parallel and supporting treatment, providing and receiving nourishment at the same time. It is only during the modern times that purely aesthetic considerations have entered in and investigation has started to find the relation between melodies and psychological tensions.

Development of Raaga in North Indian Classical Music

Development of Raaga in North Indian Classical Music took place because of great musicians who left their own personalities on the raagas they perform. Raaga is the most important concept in Indian classical music. Raaga has been derived from the Sanskrit Language word `Ranja`, standing for an element that delights and enthralls the mind. Raaga is a combination of notes illustrated by melodic movements.

Growth of Raagas

The raaga Marwa, for instance, was performed largely as an aroha-pradhana raga with its centre of melodic gravity in the uttaranga until its rendering by Ustad Ameer Khan on a long-playing record. Since then, Marwa has acquired a strong purvanga-pradhana melodic identity.

A more significant case of raaga evolution is raaga Lalit, which, according to Bhatkhande, uses the suddha dh svara. In fact, a lot of contemporary musicians consider the use of the suddha dh in Lalit. Kesarbai Kerkar`s two available recordings of Tilak Kamod also stand as an important example. In one of them, she has performed the early twentieth century form of the raaga which deploys the suddha as well as komala ni svaras, while in the second, she performs the new form, with only suddha ni.

Another facet of raaga evolution is the tendency amongst musicians to simplify the performance of ragas by introducing phrases which current grammar does not permit, but are con-textually not inconsistent with the raga`s melodic personality.

The uttaranga ascent of Kedara is also another example. The theoretical position approves of maA-pa-sa`. Over the years, musicians have varied this ascent to include maA-pa-dh-ni-sa as well as maA-pa-ni-sa.

Raagas are thus not static melodic entities. Their potency lies in their ability to develop in reaction to the creative visions of maestros and the acceptance of it by changing audience tastes.

Raagas in Modern Indian Music

Raagas in modern Indian music are a component of the new age tendency to search for newer and more varied things. This is reflected in the social and cultural fields of society. In the older times, when the musicians wanted to be off beat, they would take recourse to the nearly forgotten compositions and raagas which use to fascinate and overwhelm the listeners. However in the modern times, the musicians cannot adopt this approach. This is because there are a number of factors, such as lack of grooming under the past masters and closer contact with Carnatic music, which have led them to sing and play newly composed khayals in ragas that were nearly unheard of three decades ago. More than 100 new ragas have been added to the repertoire of about 150 existing ragas (comprising about 60 common and the rest unknown). Some of the raagas have been imported from the Carnatic musical system of ascending-descending scales, without the raaga sangatias. Some others are revivals from those imported earlier like (Hathsadhvani, Nagasvarfivali, etc.). Yet others are combinations of older patterns with new creations. Here instrumentalists, like Pt. Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Halim Jaffar, have made richer contribution than vocalists, with the lone exception of Kumar Gandharva.

Raagas in modern Indian music are a component of the new age tendency to search for newer and more varied things. This is reflected in the social and cultural fields of society. In the older times, when the musicians wanted to be off beat, they would take recourse to the nearly forgotten compositions and raagas which use to fascinate and overwhelm the listeners. However in the modern times, the musicians cannot adopt this approach. This is because there are a number of factors, such as lack of grooming under the past masters and closer contact with Carnatic music, which have led them to sing and play newly composed khayals in ragas that were nearly unheard of three decades ago. More than 100 new ragas have been added to the repertoire of about 150 existing ragas (comprising about 60 common and the rest unknown). Some of the raagas have been imported from the Carnatic musical system of ascending-descending scales, without the raaga sangatias. Some others are revivals from those imported earlier like (Hathsadhvani, Nagasvarfivali, etc.). Yet others are combinations of older patterns with new creations. Here instrumentalists, like Pt. Ravi Shankar, Ustad Ali Akbar Khan and Halim Jaffar, have made richer contribution than vocalists, with the lone exception of Kumar Gandharva.

Raagas in modern music are many in number. Some of these new ragas deserve mention here. These are: Amrit Varsini, Arabhi, Ahir-Lalit, Bairagi, Bhuparanjani, Campakall, Candramauli, Candranandana, Carukesi, Devarangani, Devakansa, Devamukhari, Gauranjanl, Gavati, Gandhi-malhara, Gauri Sankara, Girija, Gambhira-Vasanta, Guamati, Govardhana, Gauri mafijari, Harhsamanjari, Harhsanat, Hamsanarayani, Hema-behaga, Hemanta-Bhairava, Hemavau, Janaranjani, Janasammohini, Jayakamsa, Kamala Manohari, Kamala Ranjani, Kalasri, Kokila Dhvani, Khusruvani, Kiranaranjani, Lalit Kesara, Lagana Gandhara, Lajwanti, Lalit Kali, Latika, Manohari, Madhuranjani, Malarani, Malayamarutam, Modasri, Madhail, Mafijari, Mazamiri, Pranavakans, Paramesvari, Prabhakall, Pulindika, Rasacandra, Rasikapriya, Sammohini, Sarasvati, Sajana, Subhavati, Tilaksyama, Jankaradhvani, etc. Thus there has been seen an explosion of ragas in the field of Indian music.

It is interesting to note that despite this variety and growth in the number of raagas in modern Indian music, only a few amongst them have gained wider acceptance and currency among the reputed musicians. One such possible reason for the low-level acceptance of these raagas is that the higher grade musicians of today, vocalists or instrumentalists, have been tutored in the composition and ragas of the older ages, and they are averse to accepting new ragas which may prove to be novelty without creativity. Moreover, listener`s resistance is another reason, which may be due to unfamiliarity as well as aesthetic non-satisfaction. The listeners will have to get familiarized with new ragas, and for this purpose, much will depend upon their frequent and aesthetic presentation by the more acknowledged artistes of the day.

It is a known fact that excellence in music has never depended on the number of ragas and composition known to an artist. However, at the same time it is also true that much appreciation is always given to a new raaga with a distinct character and a new composition rather than a new garb in the form of a new set of words for an old body of the tune.