Introduction

Ancient Sanskrit Grammarians include Panini, Patnajali, Pingala, Shaunaka, Virahanka, Yaska,Vararuchi and Sakatayana. In Sanskrit compounds, the first word appears without terminations. From this, it is easy to differentiate stem and termination in nouns. Sakatayana announced that all nouns are derived from verbs. However, the supporter of Katyayana carried out their principle and to this period goes back in substance the Unadisitra, containing words which are derived from verbs by unusual affixes.

Contributions of Sanskrit Grammarians

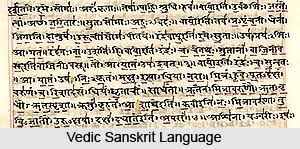

This important period of studies was concerned with the preservation and interpretation of the Vedic texts. This is visible in the preparation of the Padapatha of the Rig Veda by Sakalya. The grammarians were concerned with the spoken speech of the day and from this grew more distinct language from the sacred texts on the one hand and the speeches of the lower classes on the other. Panini cites by name many predecessors that also include Jakatayana, Apicali, and Qaunaka. Panini summarizes the efforts of many previous writers.

Role of Panini as Sanskrit Grammarian

Panini, the legendary Sanskrit grammarian, logician, and philologist of ancient India, lived during the mid-1st millennium BCE and left a mark on linguistic history that remains unmatched. His magnum opus, the ‘Aṣṭadhyayi,’ is regarded as one of the most sophisticated works of grammar ever produced. Since its discovery by European scholars in the 19th century, Paṇini has been hailed as the “first descriptive linguist” and is often celebrated as “the father of linguistics.”

Though it remains uncertain whether Paṇini physically wrote his masterpiece, textual evidence suggests he was familiar with writing systems. References in the ‘Aṣṭadhyayi,’ such as lipi or “script” and lipikara or “scribe” indicate knowledge of written forms. His work reflects a deep engagement with the scholarship of his predecessors. He cites at least ten earlier grammarians and linguists, including Apisali, Kasyapa, Gargya, Galava, Cakravarmaṇa, Bharadvaja, Sakaṭayana, Sakalya, Senaka, Sphoṭayana, and Yaska.

The “Ashtadayai” of Panini consists of about 4,000 short Sutras that are divided into eight books. It treats technical terms and rules of interpretation, nouns in composition and case relations; the adding of suffixes to roots and to nouns, accent and changes of sound in word formation and the word in the sentence. Grammar`s main objective is to deal with the living speech of the day. The major principle underlying the grammar is the derivation of nouns from verbs. All derivation is done by affixes thereby making it necessary to assume suffixes which are invisible. In Phonetics, Panini and his predecessors achieved remarkable results. The analysis of forms is carried out with great acumen.

In order to secure brevity that are aimed at many devices; the case is used, verbs are omitted, leading rules are understood and algebraic formulae replace real words. The rule that a vowel is changed into the corresponding semi-vowel is also applied. There are some technical terms that are older than Panini. The ‘Aṣṭadhyayi’ emerged from a long-standing cultural effort to safeguard the purity of Sanskrit, particularly the language of the sacred Vedic hymns, from gradual change and erosion.

While Paṇini was not the first grammarian, his work outshone and ultimately replaced earlier attempts, becoming the oldest surviving treatise of its kind in full. Panini could not teach Sanskrit. Therefore, re-writing and re-arrangement were essential, that lead to Ramachandra’s ‘Prakriya Kaumudi’ based on which is Bhattoji Diksita’s well-known ‘Siddhantakaumudi.’ On this, he wrote a comment, the Praudhamanorama. From this came two schools of grammars on Varadaraja- Madhyasiddhantakanmudi and Laghukaumudi.

Role of Katyayana as Sanskrit Grammarian

Katyayana stands out in India’s intellectual history as a remarkable Sanskrit grammarian, mathematician, and Vedic priest. Katyayana most probably lived in the third century B.C. Ancient literature, such as the ‘Kathasaritsagara,’ identifies him with Vararuci, a re-incarnation of Pushpadanta, one of Lord Shiva’s devoted ganas. According to legend, he gained mastery over grammar under the guidance of Kartikeya, the son of Lord Shiva. The Garuda Purana reinforces this account, describing how Kartikeya, also known as Kumara, taught Katyayana the principles of grammar in a manner so simple that even children could grasp its essence. This suggests that his full name may have been Vararuci Katyayana.

Katyayana’s contributions to Sanskrit grammar were profound. He is best remembered for the ‘Varttikakara,’ an authoritative commentary and expansion on the grammatical framework of Panini. Together with Patanjali’s ‘Mahabhasya,’ this work became a gem in the Vyakarana tradition, one of the six Vedangas (limbs of the Vedas) and formed an essential part of formal education in India for over twelve centuries.

It is seen that he is attacking or correcting Panini on the grounds of differences in usage which arose between the times of the two. He examined criticisms, rejecting some, accepting others thus enhancing and limiting Panini’s rules. Patanjali had many criticisms and works before him beside that of Katyayana. The variety of meters used in these verses is remarkable. It also includes some quite rare and complex meters.

Beyond linguistics, Katyayana’s intellectual pursuits

extended into mathematics. He authored one of the later ‘Sulbasutras,’ a

collection of nine treatises on the geometry of Vedic altar construction. His

work delved into precise measurements and designs involving rectangles,

right-angled triangles, rhombuses, and other geometric forms, demonstrating a

harmonious blend of linguistic mastery and mathematical precision.

Role of Patanjali as Sanskrit Grammarian

Patanjali, also known by names such as Gonardiya and Gonikaputra, is a revered figure in ancient Indian intellectual and spiritual history. Historical records and literary references suggest that the name may refer to one or more scholars, mystics, and philosophers, each contributing significantly to Sanskrit literature and thought.

Among the works attributed to Patanjali, the most celebrated is the ‘Yoga Sutras,’ a foundational text of classical yoga philosophy. Based on linguistic and thematic analysis, scholars estimate that the author of this work may have lived sometime between the 2nd century BCE and the 5th century CE.

In the realm of Sanskrit grammar, Patanjali’s most notable contribution is the ‘Mahabhaṣya’, an authoritative commentary on Paṇini’s Aṣṭadhyayi. Firmly dated to the 2nd century BCE, the ‘Mahabhaṣya’ stands as a monumental achievement in linguistic scholarship, offering critical explanations, clarifications, and expansions on Paṇini’s grammatical framework.

The Mahabhasya is interesting as it gives a lively picture of the mode of discussion of that time. The style is lively, simple and animated. Proverbial expressions and reference to matters of everyday life are also introduced. It serves both to liven up the discussions as well as to give valuable hints of the conditions of life and thought in the time of Patanjali.

Role of Pingala as Sanskrit Grammarian

Acharya Pingala was an influential ancient Indian scholar, poet, and mathematician whose work bridged the worlds of literature and mathematics. He is best remembered as the author of the ‘Chandan Sastra’ (also known as the Pingala-sutras), the earliest known treatise on Sanskrit prosody. Composed in the concise Sutra style, this eight-chapter work dates to the final centuries BCE and is considered a foundational text for the study of poetic metre in Sanskrit. It is also the earliest known Sanskrit treatise on inflection.

The ‘Chandan Sastra’ offers a systematic method for enumerating metrical patterns, such as combinations of light (laghu) and heavy (guru) syllables in verses of ‘n’ syllables. Pingala introduced a recursive approach to generate these patterns, leading to a form of binary representation unique to his system. This innovation places him among the earliest thinkers to explore combinatorics in linguistic structure.

Remarkably, Pingala’s work contains one of the earliest

explicit references to the concept of zero, using the Sanskrit term ‘Sunya’ to

denote the number. His binary notation differs from the modern form. The

sequence increases from right to left rather than left to right, and it begins

with the number one instead of zero.

Role of Shaunaka as Sanskrit Grammarian

Shaunaka

was a renowned Sanskrit grammarian and Vedic scholar whose contributions deeply

shaped the preservation and interpretation of the Rig Veda.

He is credited with authoring several important works, including the Ṛgveda-Pratisakhya,

the Bṛhaddevata, the Caraṇa-vyuha, six Anukramaṇis (indices) to the Rigveda,

and the Vidhana of the Rigveda. As the teacher of both Katyayana and Asvalayana,

he played a pivotal role in transmitting Vedic knowledge to future generations.

He is also said to have merged the Baṣkala and Sakala recensions (sakhas) of

the Rigveda, thereby unifying important strands of Vedic tradition.

Accounts of Shaunaka’s lineage vary across texts. In the Mahabharata, he is described as the son of Ruru and Pramadvara, while the Bhagavata Puraṇa names him as the grandson of Gṛtsamada and the son of Shaunaka of the Bhṛgu dynasty. The Viṣṇu Puraṇa attributes to him the formulation of the four asramas, the stages of human life.

Shaunaka is closely associated with the sacred forest of Naimiṣa. Tradition holds that during a satra-yajna, a grand twelve-day sacrificial gathering, he taught the Ṛgveda-Pratisakhya to other scholars. The Ṛgvidhana, a text detailing the ritual application of Rigvedic mantras, is also attributed to him, with his writings offering simplified versions of rites described in the Srauta and Gṛhya sutras.

His presence looms large in the Mahabharata, where he

appears as the head of a conclave of sages in Naimiṣa forest, receiving the

epic’s narration from the storyteller Ugrasrava Sauti. In one notable episode, Saunaka

consoles Yudhiṣṭhira

during his exile, offering wisdom on the nature of suffering.

Role of Bhartṛhari as Sanskrit Grammarian

Bhartṛhari stands as one of ancient Sanskrit grammarian, philosopher, and poet. A luminary of the fifth century, he was born in Ujjain, in the historic Malwa region. Although drawn toward the ascetic path in pursuit of higher truth, Bhartṛhari’s journey was marked by an enduring struggle to detach fully from worldly life. Ultimately, he lived as a yogi in Ujjain, where he continued to reflect deeply on the nature of language, thought, and existence until his final days.

His scholarly legacy is anchored in monumental works that have influenced centuries of Indian intellectual tradition. Among his most renowned writings are the ‘Vakyapadiya’, a profound treatise on the philosophy of sentences and words and the ‘Mahabhaṣyatika’, a detailed commentary on Patanjali’s ‘Mahabhaṣya’. He also authored the Vakyapadiyavṛtti, a commentary on the first two sections of ‘Vakyapadiya’, the ‘Sabdadhatusamikṣa’, and the lyrical masterpiece ‘Satakatraya,’ a collection of 300 verses reflecting wisdom, morality, and detachment.

Central to Bhartṛhari’s thought is the doctrine of ‘Sabda-Brahman,’

the idea that ultimate reality is revealed through language. He asserted that

speech and consciousness are inseparably intertwined, and that mastery over

grammar is not merely a linguistic exercise but a pathway to spiritual

liberation. His works became pivotal in shaping discourse in philosophical

schools such as ‘Vedanta’ and ‘Mimaṃsa.’

Role of Yaska as Sanskrit Grammarian

Yaska was an eminent Sanskrit grammarian and Vedic linguist who lived before Paṇini (7th–4th century BCE). He is traditionally celebrated as the author of the ‘Nirukta,’ the earliest known treatise on etymology in India and the Nighaṇṭu, regarded as the oldest proto-thesaurus in the country. In the Vedic tradition, ‘Nirukta’ is recognized as one of the six Vedangas (limbs of the Veda) essential for mastering Vedic scholarship. Yaska’s work laid the foundation for the discipline of etymology, influencing linguistic thought in both Eastern and Western traditions.

The ‘Nirukta’ is a systematic treatise that explores the origins, categories, and meanings of Sanskrit words. Building upon the work of earlier grammarians, particularly Sakaṭayana, whom he references, Yaska sought to clarify how words acquire their meanings, with a focus on the interpretation of the Vedic texts. His analysis includes rules for forming words from roots and affixes, along with a glossary of irregular terms. The text is divided into three distinct sections:

·

‘Naighantuka’ – a compilation of synonyms.

·

‘Naigama’ – a collection of words unique to the

Vedic corpus.

· ‘Daivata’ – terms related to deities, rituals, and sacrifices.

By explaining obscure and archaic words in the Vedas,

Yaska’s ‘Nirukta’ became a vital reference for priests, scholars, and

linguists. It also provided the groundwork for later Sanskrit lexicons and

dictionaries, ensuring the accurate preservation and interpretation of sacred

texts. In ancient India, ‘Nirukta,’ as a branch of the Vedangas, was a

compulsory subject for serious students of the Vedas.

Role of Shakalya as Sanskrit Grammarian

Shakalya, originally named Vidagdha, was a distinguished grammarian and scholar of the Vedic period. As the son of the revered sage Sakala, he became known by the name Shakalya. A dedicated student of the teacher Satyasri, he was associated with the scholarly lineage of the sage Paila.

Shakalya is credited with revising Vedic texts and producing the ‘Pada-paṭha,’ a meticulous word-by-word analysis of the Rig Veda. This work marked a significant step in the early study of Sanskrit, as he separated the continuous saṃhita text into individual words, even identifying and isolating the elements within compound expressions. His approach represented one of the earliest systematic methods of linguistic and phonetic analysis in Vedic scholarship.

His contributions are frequently cited by Paṇini as well as

in the Pratisakhyas, the ancient treatises on Vedic phonetics. Through his

‘Pada-paṭha,’ Shakalya not only preserved the integrity of the Rig Veda but

also provided future generations with a clear framework for understanding its

linguistic structure.

Role of Virahanka as Sanskrit Grammarian

Virahanka was a distinguished Indian scholar renowned for his expertise in prosody and his remarkable contributions to mathematics. Historical estimates place his lifetime anywhere between the 6th and 8th centuries CE, though the exact period remains uncertain. He preceded Panini. Building upon the foundational ‘Chhanda-sutras’ of the ancient scholar Pingala, who lived in the 4th century BCE, Virahanka refined and expanded the study of poetic meters, offering systematic insights that influenced later scholars.

His work became the foundation for subsequent commentaries,

most notably the 12th-century exposition by Gopala, which preserved and

elaborated upon Virahanka’s ideas. Beyond his literary and linguistic

achievements, Virahanka holds a special place in the history of mathematics as

the earliest known figure to describe the sequence of numbers now famously

recognized as the Fibonacci Sequence. This blend of linguistic mastery and

mathematical foresight places Virahanka among the remarkable polymaths of ancient

India, whose influence resonates across both literature and science.

Role of Shakatayana as Sanskrit Grammarian

Shakatayana was an eminent Sanskrit grammarian, linguist, and Vedic scholar whose work left a lasting imprint on the study of language in ancient India. He is best known for his distinctive theory that all nouns originate from verbal roots, a position that stood in contrast to the grammatical framework of his contemporary, Paṇini. He further proposed that prepositions and similar functional morphemes have no independent meaning, but acquire significance only when linked to nouns or other content-bearing words.

His grammatical philosophy was presented in the ‘Shakatayana -Sabdanusasana’, a treatise that survives only in fragments, preserved through citations by later scholars such as Yaska and Paṇini. Based on these references, it is believed that Shakatayana lived around the 7th or 8th century BCE.

Shakatayana’s legacy sustained for his focus on etymology (nirukta) and the systematic derivation of words from roots. This approach influenced the structure and methodology of later Sanskrit linguistic traditions and resonates with the philosophical principles of the Mimaṃsa school, which holds that words and their meanings are eternal.

Although his primary text has not survived in full, the

fragments that remain, reveal a scholar deeply engaged with the nature of

meaning, the function of linguistic elements, and the roots of expression. His

theories not only shaped Indian grammatical studies for centuries but have also

drawn the interest of modern scholars in comparative linguistics and the

philosophy of language.