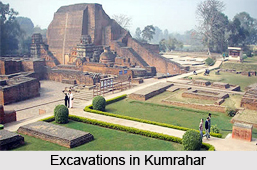

The archaeological remains of the ancient city of Pataliputra are found in Kumrahar, situated about 6 kilometres east of Patna railway station on Kankarbagh Road in Patna, Bihar. The relics found in Kumrahar include the hypostyle 80-pillared hall, Arogya Vihar which was headed by early Indian medical practitioner Dhanvantari, considered the source of Ayurveda, a Buddhist Monastery Anand Bihar and Durakhi Devi Temple. The excavations in Kumrahar collectively reflect the history of a series of four continuous periods from 600 BC to 600 AD, during the rule of three greatest emperors, Ajatashatru of Haryanka Dynasty and Mauryan kings Chandragupta and Ashoka.

The archaeological remains of the ancient city of Pataliputra are found in Kumrahar, situated about 6 kilometres east of Patna railway station on Kankarbagh Road in Patna, Bihar. The relics found in Kumrahar include the hypostyle 80-pillared hall, Arogya Vihar which was headed by early Indian medical practitioner Dhanvantari, considered the source of Ayurveda, a Buddhist Monastery Anand Bihar and Durakhi Devi Temple. The excavations in Kumrahar collectively reflect the history of a series of four continuous periods from 600 BC to 600 AD, during the rule of three greatest emperors, Ajatashatru of Haryanka Dynasty and Mauryan kings Chandragupta and Ashoka.

Ancient literature refers Pataliputra as Pataligrama, Patalipura, Kusumapura, Pushpapura or Kusumdhvaj. In the 6th century BC, it was a small village where Buddha, some time before his Nirvana, had noticed a fort being constructed under the orders of King Ajatashatru of Rajagrih, for defence of the Magadha kingdom against the Lichchavis of Vaisali. Impressed by the strategic location, King Udayin, successor of Ajatashatru, shifted the capital of the kingdom from Rajagrih to Pataliputra in the 5th century BC. For the next thousand years, Pataliputra remained the capital of the Saisunaga, Nanda, Maurya, Sunga and Gupta dynasties. It was the centre of education, commerce, art and religion. During emperor Ashoka`s rule, the third Buddhist council was held in Pataliputra. Sthulabhadra, a Jain ascetic had also convened a council here during the reign of Chandragupta Maurya.

The first account of Pataliputra and its municipal administration dates at about 300 BC, from Megasthenese, the Greek ambassador in the court of Chandragupta Maurya, who mentions it as Palibothra in his book "Indica". His account says that the city was spread in parallelogram form, stretching about 14 kilometres east to west along the river Ganges and 3 kilometres north to south. The total circumference of the city was about 36 kilometres, protected by massive timber palisades and defended by a broad and deep moat which also served as a sewer. Kautilya in his "Arthashastra" indicates wide ramparts around the city. The remains of the wooden palisades have been discovered, in addition to Kumrahar, in excavations at Lohanipur, Bahadurpur, Sandalpur, Bulandibagh and other locations in Patna.

Excavations found at Kumrahar

The excavations found at the site of Mauryan Palace in Kumrahar include:

Assembly Hall of 80 Pillars: The Mauryan pillared hall at Kumrahar was brought to light in the excavations of 1912-15, conducted by the Archaeological Survey of India (ASI) under D. B. Spooner, aided by Sir Ratan Tata. The excavation traced 72 pits of ash and rubble on the site that marked the position where the pillars must have stood. Further excavations in 1951-55 exposed 8 more such pits, including 4 belonging to the entrance or porch, giving the hall its present name of the “Assembly Hall of 80 pillarsâ€. All the pillars were made of black spotted buff sandstone monoliths with a lustrous shine typical of the Mauryan period. Given its nature, the hall has been assigned as the palace of King Ashoka, audience hall, throne room of Mauryas, a pleasure hall or the conference hall of the third Buddhist council held in 3rd Century BC during the reign of Ashoka. Amazingly, out of the 80 pillars excavated at the site, only one remains.

Arogya Vihar: Excavations also unearthed brick structures from the Gupta period, identified as Arogya Vihar, a hospital-cum-monastery, with the help of terracotta sealing discovered from the place which bears the inscription reading "Sri Arogya Vihare Bhikshusanghasya". Another red potsherd found here was inscribed with "Dhanvantareh", possibly referring to a name or title of the presiding physician Dhanvantari, the famous Ayurvedic physician of the Gupta period.

Anand Bihar: The foundations of the brick Buddhist monastery were excavated, apart from wooden beams and clay figures. The remnants are now kept for public display in the surrounding park.

Durakhi Devi Temple: The excavations conducted in 1890s by Wadell revealed a detached piece of a carved stone railing of a Stupa, with female figures on both the sides, giving it the name `Durukhi` or `Durukhiya` (meaning double-faced) Devi, a specimen of Shunga art dating back to 2nd-1st century BCE. The figures shown as grabbing and breaking branches of trees are the Shalabhanjikas (literally the breaker of branches), the young women under a fertility ritual. These images were later brought to their present location at Naya Tola in Kankarbagh, a kilometre west to the site, where they are presently worshipped in the temple-like structure. A replica of these figures has also been kept in the Patna Museum.

The excavations in Kumrahar have also revealed copper coins, ornaments, antimony rods, beads of terracotta and stone, dices of terracotta and ivory, terracotta seals, toy carts, skin rubbers, terracotta figurines of human, bird and animals and some earthen utensils. An exhibition hall tells the story of Kumrahar through antiquities, photographs, dioramas and illustrations for the convenience of visitors.

Best Time to visit Kumrahar Excavations

The ideal time to visit the Kumrahar Excavations in Patna is from October to March as the climatic conditions are quite pleasing during that time. The site is open from 9 AM to 5 PM, from Tuesday to Sunday. Kumrahar is going to have a metro station under Patna Metro.

Related Articles:

Archaeology of India

Ancient Indian Cities

Pataliputra

Ajatashatru

Haryanka Dynasty

Mauryan Kings, India

Ashoka

Chandragupta Maurya

Maurya Dynasty

Gupta Dynasty

Third Buddhist Council

Megasthenese

Archaeological Survey of India

Patna Museum