Introduction

Ahom Rule refers to the medieval kingdom in the Brahmaputra River Basin and valley in Assam that maintained its sovereignty for nearly 600 years and successfully resisted Mughal Dynasty`s expansion in North-East India. The dynasty was established by Sukaphaa, a Shan prince of Mong Mao whose arrival in Assam after crossing the Patkai Mountains started the history. The rule of this dynasty wrecked with the Burmese invasion of Assam and the subsequent annexation by the British East India Company following the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826.

Ahom Rule refers to the medieval kingdom in the Brahmaputra River Basin and valley in Assam that maintained its sovereignty for nearly 600 years and successfully resisted Mughal Dynasty`s expansion in North-East India. The dynasty was established by Sukaphaa, a Shan prince of Mong Mao whose arrival in Assam after crossing the Patkai Mountains started the history. The rule of this dynasty wrecked with the Burmese invasion of Assam and the subsequent annexation by the British East India Company following the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826.

History of Ahom Rule

Chaolung Sukaphaa (reign 1228-1268), also Siu-Ka-Pha, the first Ahom king in medieval Assam, was the founder of the Ahom kingdom. The kingdom he established in 1228 existed for nearly six hundred years and in the process unified the various tribal and non-tribal peoples of the region that left a subterranean brunt on the region. In reverence to his position in history of Assam the honorific Chaolung is generally associated with his name.

The Ahom kings were believed to be of divine origin. According to Ahom tradition, Sukaphaa was a descendant of Khunlung, who had come down from the heavens and ruled Mong-Ri-Mong-Ram. During the reign of Suhungmung (1497-1539) which saw the composition of the first Assamese Buranji and increased Hindu influence, the Ahom kings were traced to the union of Lord Indra (identified with Lengdon) and Syama (a low-caste woman), and were declared Indravamsa kshatriyas, a lineage created for the Ahoms. Suhungmung adopted the title Swarganarayan, and the later kings were called Swargadeos (Lord of the heavens).

History of Assam Rule unfurls its chapter with the treaty of Yandabo coming into force on the 24th February 1826, the sun of the 600 year old rule of the Ahoms set and Assam lost its sovereignty. Along with a few other north eastern states Assam went under British rule up to the 15th August 1947, the day India got liberated. Yet the rule of the Ahoms in Assam for long 600 years with varying power is a historical wonder. What caused fall of the kingdom was severe infighting among the nobles of the state in later part of their rule. Secondly in later pars of its rule, clash with the Satras (religious centres spreading Vaishnavism in Assam) gave rise to civil up surges in the kingdom in the shape of Moamorian Rebellion which weakened both the political power and the socio-economical structure of the state rendering total incapability to the Ahom force to resist foreign aggressions particularly the aggressions of the Burmese (Maan) which broke the backbone of the Ahom monarchy.

History of Assam Rule unfurls its chapter with the treaty of Yandabo coming into force on the 24th February 1826, the sun of the 600 year old rule of the Ahoms set and Assam lost its sovereignty. Along with a few other north eastern states Assam went under British rule up to the 15th August 1947, the day India got liberated. Yet the rule of the Ahoms in Assam for long 600 years with varying power is a historical wonder. What caused fall of the kingdom was severe infighting among the nobles of the state in later part of their rule. Secondly in later pars of its rule, clash with the Satras (religious centres spreading Vaishnavism in Assam) gave rise to civil up surges in the kingdom in the shape of Moamorian Rebellion which weakened both the political power and the socio-economical structure of the state rendering total incapability to the Ahom force to resist foreign aggressions particularly the aggressions of the Burmese (Maan) which broke the backbone of the Ahom monarchy.

Ancient history of Ahom Rule

The Ahoms arrived with the knowledge of the technology of wet rice cultivation that they shared with other groups. The peoples that took to the Ahom way of life and polity were integrated into their fold in a process of Ahomization. As a result of this process the Barahi people, for instance, were completely subsumed, and some of other groups like some Nagas and the Maran peoples became Ahoms, thus enhancing the Ahom numbers significantly. This process of Ahomization was particularly significant till the 16th century, when under Suhungmung, the kingdom made large territorial expansions at the cost of the Chutiya and the Kachari kingdoms.

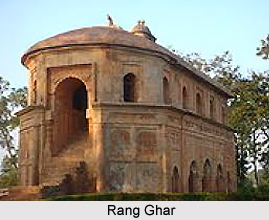

Rang Ghar, a pavilion built by Pramatta Singha (also Sunenpha; 1744-1751) in Ahom capital Rongpur, now Sibsagar; the Rang Ghar is one of the earliest pavilions of outdoor stadia in South Asia. The expansion was so large and so rapid that the Ahomization process could not keep pace and the Ahoms became a minority in their kingdom. This resulted in a change in the character of the kingdom and it became multi-ethnic and inclusive. Hindu influences, which were first felt under Bamuni Konwar at the end of the 14th century, became significant. The Assamese language entered the Ahom court and co-existed with the Tai language. The rapid expansion of the state was accompanied by the installation of a new high office, the Borpatrogohain, at par with the other two high offices and not without opposition from them. Two special offices, the Sadiakhowa Gohain and the Marangikowa Gohain were created to oversee the regions won over from the Chutiya and the Kachari kingdoms respectively. The subjects of the kingdom were organized under the Paik system, initially based on the phoid or kinship relations, which formed the militia. The kingdom came under attack from Turkic and Afghan rulers of Bengal, but it withstood them. On one occasion, the Ahoms under Tankham Borgohain pursued the invaders and reached the Karatoya River, and the Ahoms began to see themselves as the rightful heir of the erstwhile Kamarupa Kingdom.

Later history of Ahom Rule

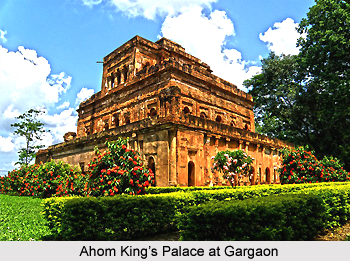

The kingdom came under repeated Mughal attacks in the 17th century, and on one occasion in 1662, the Mughals under Mir Jumla occupied the capital, Garhgaon. The Mughals were unable to keep it, and in at the end of the Battle of Saraighat, the Ahoms not only fended off a major Mughal invasion, but extended their boundaries west, up to the Manas river. Following a period of confusion, the kingdom got itself the last set of kings, the Tungkhungia kings, established by Gadadhar Singha.

The rule of Tungkhungia kings was marked by peace and achievements in the Arts and engineering constructions. The later phase of the rule was also marked by increasing social conflicts, leading to the Moamoria rebellion. The rebels were able to capture and maintain power at the capital Rangpur for some years, but were finally removed with the help of the British under Captain Welsh. The following repression led to a large depopulation due to emigration as well as execution, but the conflicts were never resolved. A much weakened kingdom fell to repeated Burmese attacks and finally after the Treaty of Yandabo in 1826, the control of the kingdom passed into British hands.

Religion under Ahom Rule

Hindu influence first entered the Ahom court during the reign of King Sudangpha Bamuni- onwar (1397-1407), who had been brought up in a Brahmin family. The Hindu influence was more marked in the reign of King Pratap Singha who was personally grateful to Brahmin priests for ridding him of a demon which had possessed him during his prince hood. The first Ahom king to accept Hinduism formally was, however, Jayadhvaja Singha. Jayadhvaja Singha and his successors up to Lora Raja were initiated in Vaisnava faith. Gadadhar Singha persecuted the Vaisnavas, and bestowed royal patronage upon the Saktas and showed great honour and courtesy to Sakta priests. When his son, King Siva Singha, became a disciple of a Sakta Brahmin, the Saktas got into ascendancy. Credit must be given to the tribal friendly Ahom monarchy in diluting the caste system in Assam and removing untouchablity, in particular, to a great extent

Assamese Religious Epics during Ahom Rule depict the ongoing plethora of religiosity in the epics. Comparatively few books were written during this age on themes of the two epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. One of the leading poets who enjoyed great reputation in the later part of the eighteenth century and who drew on the Ramayana story was Raghunath Mahanta. Raghunath`s fame as a poet rests on his two long narrative poems Adbhuta-Ramayana and Santrunjaya; both appear to have been based on some floating Ramayana legends.

Assamese Religious Epics during Ahom Rule depict the ongoing plethora of religiosity in the epics. Comparatively few books were written during this age on themes of the two epics, Ramayana and Mahabharata. One of the leading poets who enjoyed great reputation in the later part of the eighteenth century and who drew on the Ramayana story was Raghunath Mahanta. Raghunath`s fame as a poet rests on his two long narrative poems Adbhuta-Ramayana and Santrunjaya; both appear to have been based on some floating Ramayana legends.

Raghunath`s Ramayana

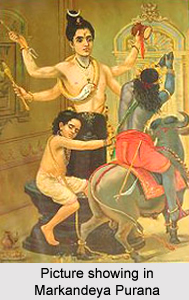

According to the poet, the source of adbhuta-Ramayana is the Markandeya Purana. The story relates to Sita in the Nether World (Patala) after her final estrangement from her consort, Rama. After having parted from Rama for good Sita was living in Vidyabilasinlpura of the Nether World. But she had lost her peace of mind. She had left behind her husband and her two beloved sons, Lava and Kusa.

The pangs of separate on pierced her heart day and night. In Ayodhya, Lord Rama was pining for the company of his beloved wife. His agony was still deeper. It was because of his unkind innuendos that Sita had been compelled to beg her mother, the Earth, to rend herself asunder so that she might find solace in her bosom. Sita asked Vasuki, the king of Serpents in the Nether World, to abduct Lava and Kusa from Ayodhya. Vasuki made an abortive attempt and reported his failure to Sita. He found it impossible to break through the hosts of invincible warriors like Hanumanta, Nila, Nala, Vibhisana. Sita understood his difficulty, but implored him to try again, this time by using his magical power. Accordingly, Vasuki went in the guise of a Brahmin and, on the pretext of training Lava and Kusa in archery, brought them from Rama. Having thus fulfilled his mission, the disguised Brahmin succeeded in persuading the princes to accompany him to Vidyabilasinipura where their mother lived. Vasuki then arrived at Patala where the mother and the sons met to their unbounded joy and happiness. This treachery of Vasuki infuriated Rama so much that he at once ordered his courtiers to find out Lava and Kusa from wherever they might. Everybody tried his utmost but to no avail. At last the task was entrusted to Hanumanta, who, by virtue of his great magical power, adopted many subtle devices. He had very tough fights with the serpents and the Serpent King. At last he defeated all of them, ferocious and frightening as they were, and brought Sita and her two sons back to Rama.

Naturally Rama`s joy over the reunion knew no bounds. Sita made obeisance to Rama, but urged him not to press her to live with him as she was not destined to do so. She assured him, however, of her daily visit, which would be visible only to Rama, Lava, Kusa and Hanumanta. Sita then vanished into the air.

Santrunjaya`s Ramayana

In Santrunjaya, the Rama legend is treated very briefly as a sequel to another story. The author`s intention was not so much to tell the well known story of Rama as to narrate the exploits and expeditions of Bali and Hanuman. The first part of the story which describes these exploits in detail is very amusing, and seems to be the poet`s own invention. The poem begins with the author`s invocation to Visnu who in his different incarnations on this Earth did away with corruption, vice and injustice and established the kingdom of justice, truth and virtue. The narrative begins as in a Purana with a dialogue between Valmiki and Bharadvaja, the former relating to the latter how and why the gods became monkeys. Brahma, the Preserver, was one day presiding over an assembly of the gods in Manivatipura on Mount Meru. The gods, including Sumeru, King of Meru, attended the assembly accompanied by their daughters. All of them enjoyed the graceful dances of the charming Vidyadhari maids. Sulocana, daughter of Sumeru, unsurpassed in beauty, made all the gods spellbound with her graceful dance. Everybody wanted to marry her. The wind-god Vayu, one of the prominent gods, decided to make advances to Sulocana`s father with the intention of asking his daughter`s hand and sent a messenger to this end, along with a letter to Sulocana herself requesting her to accept him in wedlock. The messenger accordingly informed Sumeru of the purpose of his mission, but the latter turned down the proposal flatly. Being at a loss, the messenger prayed to Vayu to send a puff of gentle breeze. This was sent, and the messenger had the letter borne by the breeze to Sulocana who, having read the letter, laughed away the strange proposal. At this Vayu flew into a rage and declared war on Sumeru. A fierce battle broke out. The gods were frightened and prayed to Brahma to bring about a settlement. Brahma commissioned Narada who brought about a compromise between the contending parties.

According to the terms of the compromise, Sumeru gave away to Vayu one of his summits, the Vihanga Srnga, which was blown away by Vayu to the Milk Ocean (Ksira Sagara) where lay Mount Trikuta. On this mountain fell the Vihanga Srnga. When Vishwakarma, the architect of this universe, found this Vihanga Srnga, he carved out on it a beautiful city known as the golden city of Lanka. In this city lived Mali, Sumali and Malyavanta, the three Raksasa brothers. Vishnu beheaded Mali with his disc (cakra), and the two other brothers fled for dear life.

Then came in the scene Kuvera, King of Lanka; One day Sumali found Kuvera on the throne, and bewailed the deplorable lot of Raksasas who had been driven to recapture Lanka. He had given his daughter Naikesi in marriage to Visrava, father of Kuvera, in the belief that Visrava would restore the lost kingdom. Naikesi conceived in her `unclean period` (during menstruation) and was afraid of the progeny, who, according to popular belief, would be notorious for their violence and evil-doing. During the period of her conception, evil omens were sighted everywhere. Everybody on earth and in heaven got panicky. In view of the universal fear and impending menace, Naikesi retained the bitter fruit of her womb for one hundred years. But the panic was all along there. The gods went to Brahma who told the former that the danger was real and imminent. He then explained how Jaya and Vijaya, the two gatekeepers of Lord Vishnu, who were cursed to be born to Diti first, were both of them being cursed by Goddess Laksmi again, in the womb of Naikesi now. He finally told them that the moment they were born there would be no end to the miseries and distress of people and that Visnu alone could overcome the calamity. Brahma then lay in a deep trance awaiting the `unbodied message` of Visnu, the Supreme Power of the universe. The message came that there would be an incarnation of Visnu Himself to put an end to the menace. The gods were ordered to be reborn on earth as monkeys. Brahma was directed to be reborn as a bear, Vayu as the monkey Kesari, Indra as Bali, the monkey-king of Kiskindhya, and thus all the gods and goddesses were directed to become monkeys. Some of the monkeys would be savage and would plunder and pillage one kingdom after another until at last they would reach Kailasa where Nandi, God Mahadeva`s disciple, would persuade them to assault Kiskindhya, the kingdom of the mighty king, Bali, who would conquer them.

Brahma intimated to the gods all that he had heard, and in course of time all were reborn as desired by God. Bali went out on world-conquest. In the course of his march he found a tender-aged monkey throwing stones at the fruits of a tall mango-tree. Bali saw to his great surprise that the monkey-boy was physically too strong to be ignored, and so Bali, instead of using force, had the monkey persuaded by one of his ministers to be the adopted son of Bali who pretended that he had no son to call his own. The monkey boy agreed to the proposal and became his adopted son. Asked about his birth and name, the monkey replied that he was son of Kesari. His mother was Anjana, and his name was Hanumanta. Immediately after his birth, he climbed the mountain Lokaloka where he saw a huge elephant. He could not check the temptation to mount the elephant, which presently began to groan under the weight of the boy monkey and almost collapsed. But the bushy and pointed hair on the back of the elephant pricked him and caused severe pain. So he jumped down and faced the elephant, challenging him with his tail raised. His attitude frightened the elephant so much that the latter ran for life, and in this way Hanumanta defeated eight such elephants. This act of Hanumanta displeased his father and made him very angry. He admonished Hanumanta; for the elephants whom he had given so much trouble were none other than eight incarnations of God, who had borne this earth on their backs. Hanumanta politely replied that since the earth itself had been borne by God, it was absurd to accuse him as one guilty of mounting them. Moreover, God is all-pervasive and the soul of every living being is an inalienable part of that Supreme Soul. So what one did was done by God Himself. Hence he pleaded not guilty, adding that he was always ready and happy to do whatever his father would bid. Kesari was moved. As desired by his son, he ordered him to serve pilgrims and devote himself to Rama heart and soul. Bali was much pleased with the story of Hanumanta and appointed him commander-in-chief of his powerful army. It was now that the real adventure began, and the succeeding verses tell of Hanumanta`s deeds. In no time Hanumanta brought one monkey-king after another under the suzerainty of Bali.

He attacked the demon king Bhauma, son of Dharani. Bhauma got the help of Dhananjaya, a prominent king of the Nether World. He helped Bhauma with his innumerable serpent-soldiers. Kankana was his great general. This was a formidable alliance. There was an `unbodied message` from heaven that it would be next to impossible to defeat Dhanafijaya Naga who possessed `Sarangadhanu` and `Narayani Astra`. He, therefore, called upon Rama to help him. A golden chariot with some invincible weapons in it came down from heaven. Hanumanta got into it and a fierce battle followed resulting in Hanumanta`s victory. Thus Hanumanta conquered all the notorious serpent-kings who helped Bhauma. The news upset Bhauma who immediately went to Mangala (the planet Mars) and wanted to know from him if Bhauma should fight with Hanumanta. Mangala laughed away the idea of fighting with a petty monkey. Meanwhile, a serpentking, who had fought with and been defeated by Hanumanta, arrived there and told them that it would be absurd to fight with Hanumanta who had no parallel in warfare. Bhauma realised the situation and withdrew. In the meantime, Gajaketu encouraged Hanumanta to march to Sakadvipa. Hanumanta ordered his armies to start by Yogapatha. They got down at the mountain Isana where they met a large number of very beautiful monkeys. They came to know that Nala was their king and they were the direct descendants of the Gandharba, Citraratha. Hanumanta, along with Satavali and Dividha, then went to Nala and told him of their mission. Nala replied that he was a devoted disciple of Rama. At this Hanumanta`s joy knew no bounds, and they became true comrades. Hanumanta now enquired about the kings of Sakadvipa who were to be conquered. Nala supplied all the information. Strengthened by the company of great warrior like Nala, Hanumanta fought with vigour and defeated all the kings concerned and compelled them to surrender. Most of the kings were, however, devotees of Rama, and so the victory was pleasant and easy.

Then Hanumanta arrived at an island called Baimanika where one Rudrabahu ruled. The people of that land used to fly in airplanes. Passing by Baimanika, Hanumanta at last reached the city of Puskalini which was his birth place. There he bowed to his parents who blessed him, wished him a long life, and inquired about his exploits. Hanumanta told them of all that he had done. Now he sent all the vanquished kings to Bali. But the monkey-kings of Lokaloka Mountain were yet to be conquered. Moreover Bali desired the company of Hanumanta`s parents whom Hanumanta wanted to take with him to Bali. While the three had such conversations, they welcomed Narada who expressed joy at the victory of Hanumanta but forbade Hanumanta to attack the monkey kings of Lokaloka, for they were destined to be conquered by Rama who was going to incarnate himself very soon. Then Narada asked Hanumanta and his parents to leave for Bali`s capital. Hanumanta consented and asked his mother Anjana to take the charge of two princesses, daughters of Susena, and train them in such a way that they might be worthy queens. Then along with his father, he went to Bali, who was naturally much pleased. Hanumanta proposed that Bali and his brother be pleased to marry the two pretty daughters of Susena. Bali agreed and, after his marriage, left for Kiskindya, where he began to live amidst royal pomp and grandeur.

The story of Bali`s adventures ends here. The author then adds a new chapter describing Rama`s birth and banishment, the abduction of Sita by Ravana, Rama`s fight with Ravana - practically the whole Ramayana in a nutshell, including the story of Lava and Kusa. The long poem ends with a prayer to Visnu. The aim of the poet was, no doubt, to depict Rama as an incarnation of Visnu and also to propagate the tenets of Bhakti. This he certainly achieved. But he also deserves praise for handing down these entertaining Rama-legends which would otherwise have been consigned to oblivion. The poems reveal the poet`s acquaintance with the floating Jaina versions of the Ramayana.

Language, Literature during Ahom Rule

Mass education was absent in the Ahom kingdom. Even most of the nobles and kings were unschooled and were rather schooled in warfare and in administration. Perhaps the economy of the state did not permit opening schools for the masses or it might be the wish of the crown to keep the common subjects unschooled. However, the Ahom priest clans namely the Deodhais, the Bailungs and the Mohans continued their schooling in Ahom language, they also wrote Buranjis(history/royal diaries) in Ahom languge and Ahom language continued to be the court language almost to the end of the Ahom regime. The practice of writing Buranjis started from the days of the founder king Hso-Ka-Hpa. Hasti bidyarnav, a pictorial Hand-Book on elephant written in Assamese during the middle part of the Ahom regime is a master piece of its kind in the whole world. Another remarkable literary work of that time was Religious Epics during Ahom Rule like Ramayana to Assamese language by Madhab Kandali in the fourteenth century under patronage of the Barahi king, Mahamanikya.

Art and Culture during Ahom Rule

Even though the Royal house did not impose anything of their Tai culture and social customs on the subjects, yet all the good customs and culture flew into the Assamese culture thus a strong fabric of national cultural assimilation was woven. The Assamese musical instruments dhol (drum) was brought by the Ahoms from the Shan country, Maolung. Maihang, Bankahi, Banbati, Sharai, etc. the dishes and utensils used by the Ahoms became popular among other communities of Assam, as well. Assamese ornaments like Jangphai, Jonbiri, Gam Kharu etc. and dresses like Khingkhap, ahom Mekhela are all of Ahom origin. Muga silk worms were first reared by the Ahoms. The costumes prepared with Muga golden silk fabrics are still regarded as the dresses of national honour and dignity in Assam. The plain Janpis and floral Janpis used by the Ahoms became popular headgears for other tribes also.

Ahom People

The Tai Ahoms who came into Assam followed their traditional religion and spoke the Tai language. They were a very small group numerically and after the first generation, the group was a mixture of the Tai and the local population. Over time the Ahom state adopted the Assamese language and kings and other high officials converted to Hinduism. Except for some special offices (the king and the raj mantris), other positions are open to members of all tribes and religion. They kept good records, and are known for their chronicles, called Buranjis.

Downfall of Ahoms

Their power declined in latter half of the 18th century. The capital city was taken for a short period during the Moamoria rebellion. In the first part of the 19th century, the Burmese army invaded their kingdom that set up a puppet Ahom king. The Burmese were defeated by the British in the First Anglo-Burmese War resulting in the Treaty of Yandaboo in 1826, which paved the way for the British to convert the Ahom kingdom into a principality and which marked the end of the Ahom rule.

Ahom rule in Assam depicts the overall development of Assam from politics to literature to economy etc. The most distinctive aspects of the period, as noticed earlier, were the geographical and racial unification of the country, stabilisation of the political institutions, organisation of the economic, social and religious systems, and the rise of cultural nationalism.

Administration under Ahom Rule

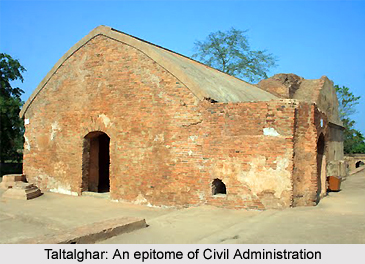

Administration under Ahom rule reveals the style and functions of the Ahom rule in Assam was not purely a monarchy system but an aristocrat government formed by the nobles namely (Borhagohain, Borgohain, Barpatragohain, Borbauah and Borphukan), and the king was more or less a nominal head of the kingdom.

Administration under Ahom rule reveals the style and functions of the Ahom rule in Assam was not purely a monarchy system but an aristocrat government formed by the nobles namely (Borhagohain, Borgohain, Barpatragohain, Borbauah and Borphukan), and the king was more or less a nominal head of the kingdom.

History of Administration under Ahom Rule

Ahom society was a traditional society with traditional administration. Ahom administration was monarchical with lots of democratic values where the monarchy was the normal form the Government although it was somewhat peculiar." The Ahom administration was partly monarchical and partly aristocratic. The Ahom had a well organized administration which was a hierarchical system with several levels. A discussion about different officials, dignities and portfolios of the administration of Ahom can clear the model of that administration. The Ahom rule was again single feudal system where the land owned to the crown only; the nobles and the subjects were simply user of the lands. This mono feudal system facilitates a widespread control of the monarchy over the subjects. Introduction of Paik system in the kingdom can be termed as a systematic exploitation of Ahom rule. However in the middle part of the Ahom rule, there were land allocations to the Satras and other religious shrines of Assam in the shape of Devottor lands.

Structure of Administration under Ahom Rule

There was a marked stratification in the body of Ahom administration. The king known as called as Sargadeo in Tai language was the virtual head of the state. Generally the son of the king became the next king. If the king had more then one son than the selection of the king was depended upon the collective decision of the Gohains.

The council of five Ministers were in the next level in Ahom administration. "They were altogether knows as patramantri which included the Borgohain, the Burhagohain, Barpatragohain, Barbaruah and Barphukan.

There were three Gohains in Ahom administration. The king had to consult with these Gohains who had the power to determine the succession of the monarch. The BarBaruah had to perform three fold functions- Administrative, Judicial and Military. Barphukan was entrusted with the responsibility of maintenance of diplomatic relations with Bengal, Bhutan etc.

They had the tradition of appointing some other local governors like Sadiakhowa Gohain, Marangikhowa Gohain etc. Besides that, Ahom kingdom also allowed some lesser kings who were known as Puwali Rajah. Phukan were the subordinate officials of Barbaruah and Barphukan. Both Barbaruah and Barphukan had six Phukan under them.

The Khels were the organized form of Paiks with certain gradation.

The paik system was one of the unique arrangements of Ahom administration who were the labour cum soldier of Ahom administration. The paiks had to indulge themselves in agriculture and other developmental activities in normal situation and in war they had to serve as soldiers. These paiks were organized in Gots. Each Got contained four Paiks.

Military Administration under Ahom Rule

Population at that time in Ahom kingdom was not enough, sufficient manpower was never received for serving as soldiers in the battles fought against enemies invading the land. The Ahoms, therefore, adopted some improvised warring techniques to fight the enemies. They raised ramparts to resist movement enemy cavalries. The Ahom soldiers were expert in river battles. So by erecting ramparts they used to call the invaders to river battles so that the enemies were controlled and defeated easily. They were even known to have use under water ramparts to resist movement of enemy boats by suspending big blocks of stones from catenaries made of canes, etc. The Ahoms adopted mostly guerrilla warfare techniques in fighting the enemies. In most of the battles, fought against the Mughal forces, the Ahoms could organize supports from the local tribes. The weapons used in those days were Hendang( a typical Ahom sword), spears, bows and arrows, Bortoops (Ahom canons),etc. The Ahoms could not maintain a regular army. The same paik who is basically a cultivator had to fight in the battle field when there was any foreign aggression on the land. This was a serious drawback in Ahom military set up. When a large section of the paiks joined the Moamoria Rebellion, it is seen that Monarchy failed to arrange a force with sufficient number of soldiers to resist the revolt. So was the case during the Maan attacks.