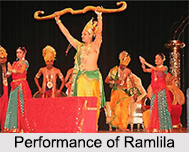

Martial Themes in Nautanki forms a critical part of the folk theatre from north India. The great ruler Harishchandra exemplifies the kingly paragon: learned, judicious, beneficent, and utterly devoted to truth. His most common epithets in the Nautanki theatre are Satyavadi, "he who speaks truth," and satyasindhu, "ocean of truth." Truthfulness, or adherence to Satya or sat, signifies more than not telling lies. It connotes an attitude of righteousness extending to all aspects of conduct, guided by a constant searching to determine the nature of truth. In practice, holding to truth means fulfilling promises, following up on bonds of trust established in good faith. Harishchandra is also famed for his generosity; he is a great bestower of gifts, a dani. It is Harishchandra`s penchant for keeping his word coupled with his largesse that precipitates his fall when, tricked by the gods, he gives away more than he has.

Story of Harishchandra

Harishchandra, ruler of Ayodhya, is a rich and virtuous king who has performed ninety-nine sacrifices (Yajna) and must accomplish only one more to gain liberation. Indra, the king of the gods, feels threatened by Harishchandra`s escalating fortunes, and he sends the sage Vishvamitra to obstruct the king. Vishvamitra in the form of a boar uproots a garden in the vicinity of the palace, and when Harishchandra comes to slay him, he changes his disguise to that of a Brahmin. Challenging the king`s reputation as a truth sayer, he requests two boons, and Harishchandra agrees. He commands that the king bestow his entire kingdom upon him as a religious donation (dan), and on top of that he asks for his priestly honorarium (dakshina). Since Harishchandra has given away all he possesses with the first boon, he is forced to sell his wife and son into slavery in order to pay off the second.

Harishchandra, his wife - Taravati and their son, Rohit starts a journey to Varanasi. A Brahmin purchases Taravati and Rohit, but an untouchable buys Harishchandra and sets him to work at the cremation ground collecting the tax on dead bodies. He suffers not only the pollution of the death rites but hard labour, starvation, and the indignity of servitude. One day Rohit is bitten by a snake and dies. When Taravati brings his body to the cremation site, Harishchandra is compelled to demand the tax that she is too poor to pay. Denying herself the modesty that is her only remaining possession, she shreds her sari and gives Harishchandra a piece of it instead of the tax. After Rohit`s body is cast into the Ganges, Vishvamitra retrieves it and brings it to Taravati, raising rumours that she is a witch. Because untouchables serve also as executioners, Harishchandra is appointed to behead her. However, just as he raises his sword, the gods appear. Harishchandra is cleansed, reunited with his son, and given direct passage with his family into heaven.

As recorded earlier in the epics and Puranas, where rulers and priests often competed for power and merit - this myth may once have been intended to warn against the hubris of excessive virtue among the royalty. By its nineteenth-century appearance in theatre, however, the display of Harishchandra`s forbearance had become a set piece, comparable to the labours of Sisyphus or the torments of Job. The king`s suffering induces pathos because of its lack of provocation; it comes upon him randomly, as every good person`s hour of trial seems to come. If even the mightiest and lauded individual in the land can suddenly find himself shorn of all privilege, degraded and outcast, how tenuous the happiness of any human being must be. The story reverberates with familiar slogans on the inscrutability of destiny. It recommends a course of action that rewards acceptance of subjugation and diligent perseverance - if not in this birth then surely in the next.

Within this framework, the folk theatre works its magic in the mode of exaggerated contrasts of feeling. The Nautanki text exploits the ironies of lost rulership especially through the tender figures of the wife and child. These pawns in the king`s moral battle with the gods become foci of intense pathos and melodrama. Harishchandra is not only unable to protect his kingdom; he cannot help those who are his most intimate dependents. As he witnesses their degradation, he suffers doubly for his incapacity to succour them. The ultimate blow is of course Rohit`s death and Taravati`s near death, in which he is an unwilling accomplice.

Through the reversals written into the story line, the narrative dismantles pat metaphysical explanations, exposing the contradictions at the heart of the moral system. It is not enough that the king pursue truth with utmost vigour. The drama deconstructs the very concept of truth, distilling its ultimate cruelty and blindness to human desire. Let us take the most memorable scene in the drama, when Harishchandra is called upon to execute his own wife. The act of beheading Taravati has the radical potential to undermine the truth of the king. It dramatizes the possibility that his descent to untouchability has destroyed his former capacity for virtue: he is beyond the pale socially and morally, not only unable to do good but compelled to do evil. The wife`s murder is necessary as the logical extension of the reversal in the king`s fortunes, denying the accumulation of goodness as much as wealth.