Introduction

Indian paintings in medieval age evolved mainly during the age of the Mughals and consisted of several kinds of paintings like Rajput paintings, Mughal paintings, miniature paintings, Tanjore paintings and numerous others. The subjects of such paintings were influenced by mythological tales, figures and religious stories. Medieval Indian paintings also included masterpieces inscribed on palm leaves or `patra lekhana`. Wall paintings were extensively practiced even in the medieval era.

Early Manuscript Illustration and Format

Medieval Indian painters primarily worked on palm-leaf manuscripts, which dictated a specific format, long and narrow, usually around 55 by 6 centimeters. This shape remained largely unchanged even after the introduction of paper in the late 14th century, preserving the aesthetic and structural identity of early illustrated texts.

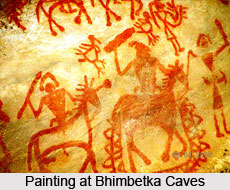

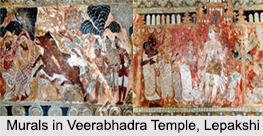

One of the earliest traces of mural painting from the

medieval period can be found in rock-cut temples, especially those in

Thirumalapuram and Sittannavasal, dating back to the mid-9th century. These

murals are characterized by their minimal color palette—white, indigo, black,

and pale blue and display a calm sophistication in composition. Later, during

the Chola period (11th century), fresco painting flourished in temple complexes

such as Narthamalai and Malayadipatti, where surviving fragments reveal further

refinement and spiritual depth.

Schools of Painting in the Medieval Age

During medieval times, Indian painting evolved through distinct regional schools, each reflecting the religious, cultural, and material influences of its time. Much of the artistic activity was centered around manuscript illustration and mural painting, with notable developments in three key regions: Bengal in the east, Gujarat in the west, and Mysore in the south.

Bengal School of Painting

In the eastern region of Bengal, under the rule of the Pala

and Sena dynasties, a Buddhist school of painting emerged during the 11th and

12th centuries. This style eventually migrated to Nepal in the 13th century.

Renowned for its delicate line work and adherence to traditional Buddhist

iconography, the Bengal

school favored a limited but effective palette, often using indigo,

cinnabar, green, and yellow to create subtle depth and relief in imagery.

Gujarat School of Painting

In western India, the Gujarat school thrived between the

12th and 14th centuries within a strong Jain cultural context. This school is

notable for its distinctive artistic language. It displays stylized figures

with large, three-quarter-view eyes and intricately detailed compositions. The

use of vibrant red backgrounds was a hallmark of the school until the 15th and

16th centuries, after which blue backgrounds became more common. The Gujarat style,

marked by precision and ornamental richness, remained influential well into the

17th century.

Mysore School of Painting

In southern India, under the Hoysala dynasty (11th–13th

centuries), Mysore developed its own painting tradition. A notable example is a

palm-leaf manuscript dated to 1113 CE, illustrating a Jain narrative. While

less polished than the Pala school works, Mysore paintings

stood out for their lively and expressive character. These illustrations were

often framed with elegant plant or geometric motifs that visually separated the

artwork from the accompanying text.

Types of Paintings During the Medieval Age

The medieval period in India witnessed significant shifts in political power following the decline of the Gupta Empire. While large-scale artistic endeavors saw a temporary slowdown during the 11th and 12th centuries CE, this era quietly nurtured a rich tradition of illustrated manuscripts that would come to define medieval Indian painting.

Religious devotion played a pivotal role in the art of this period. Manuscript illustration became a central mode of artistic expression, with texts rooted in Jainism, Buddhism, and Hinduism receiving detailed visual treatment. These manuscripts not only preserved sacred knowledge but also showcased intricate artwork that reflected the spiritual beliefs and cultural values of their time.

The influence of Buddhism and Jainism was especially prominent, with their artistic footprints extending across both eastern and western India. Buddhist monasteries and Jain temples became vibrant hubs of manuscript production, where artists brought religious narratives to life through finely detailed and vividly colored paintings on palm leaves and, later, paper.

Several regional dynasties played a crucial role in

encouraging artistic expression. In the east, the Pala rulers emerged as major

patrons of Buddhist

art, supporting the creation of beautifully illustrated texts filled

with serene and symbolic imagery. In western India, the Rajput courts and Jain

communities promoted painting that emphasized stylization and ornamentation.

Meanwhile, in the southern regions, the Cholas and Chalukyas invested in both

temple art and manuscript illustration, helping to sustain and evolve the

visual culture of the time.

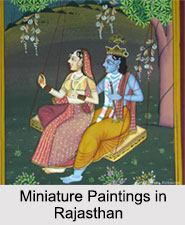

Miniature Paintings

Indian miniature paintings were born in the 17th century and

flourished during the reign of the Mughals, Hindu kings

of Rajasthan and

the Muslim rulers of the region of Deccan.

They were believed to be inspired by mural paintings which evolved around the

latter portion of the 18th century. The influence of the Mughals on miniature

paintings is evident from the Persian motifs and style. Miniature paintings in

India are quite attractive, though they are quite small in size. The colours

employed are usually handmade and extracted from minerals, vegetables, conch

shells, indigo, precious stones and metals like silver and gold.

Delicate and skilled brushstrokes impart a unique visual appeal to these

miniature paintings. Indian ‘ragas’ are the most common themes of miniature

paintings. Various schools across the nation provide lessons in miniature

paintings like Pala School, Jain School, Rajasthani School, Mughal

School and Odisha School.

Jain Miniature Paintings

During the medieval era, Jain miniature painting

emerged as a significant artistic tradition, flourishing under the patronage of

wealthy Jain merchants and rulers in Gujarat. While Buddhist manuscript

illumination reached its zenith in the regions of Bihar and Bengal, the Jain

style developed its own distinctive identity, blending religious devotion with

refined craftsmanship. These paintings were primarily executed on palm leaves,

which served as both the canvas for the artwork and the surface for

calligraphic text. The format retained the influence of earlier wall painting

traditions, yet incorporated clear elements of local folk aesthetics such as

vibrant colors, stylized figures, and intricate decorative motifs that

reflected regional cultural tastes.

The manuscripts were created as loose sheets of palm leaf,

meticulously bound together with thread and protected by wooden covers. Far

from being mere functional bindings, these covers were works of art in their

own right. Their inner surfaces richly painted with ornamental patterns or

miniature scenes that complemented the manuscripts they enclosed.

Pala Miniature Paintings

Pala school of

miniature painting represents one of the earliest and most celebrated

traditions of manuscript illustration in medieval India. Its origins can be

traced to the 10th century CE, during the reign of Mahipala, a devoted follower

of the Mahayana Buddhist tradition. Some of the finest surviving examples come

from palm-leaf manuscripts of the sacred text 'Astasahasrika Prajnaparamita.'

Characterized by delicate, flowing outlines and sensuous facial expressions, Pala miniatures embodied both spiritual devotion and artistic refinement. These works were often commissioned by lay devotees, monks, and even princes, primarily as offerings to gain religious merit.

Creating these manuscripts involved a meticulous and time-intensive process. The palm leaves, initially fragile, were replaced over time with a more durable variety known as Shritada. Before they could be painted, the leaves underwent elaborate preparation- they were submerged in water for a month, dried, polished with conch shells to achieve smoothness, and then cut into uniform rectangular strips.

Once the sacred text was inscribed, typically five to seven lines per leaf, a reserved space was left for miniature illustrations. The painting process itself was highly sophisticated. A background color was applied first, followed by the preliminary drawing. Figures were then filled with vibrant hues, with shading and highlighting used to create depth and form. The final step involved defining the details with fine black or red outlines, giving the images their distinctive clarity and elegance.

Ragamala or Rajasthani Painting

Rajasthani painting reached artistic maturity during the

16th century CE, developing a distinctive style that reflected both regional

traditions and evolving cultural influences. The early works of this school are

marked by their characteristic protruding eyes, stylized facial features, and

depictions of figures dressed in the contemporary costumes of the time.

By the latter part of the 16th century, exposure to the refined techniques of miniature painting began to transform the Rajasthani style. The compositions became more detailed, the color palette richer, and the overall aesthetic more sophisticated. Several vibrant artistic centers emerged, including Mewar, Bundi, Kota, Pratapgarh, Kishangarh, and Malwa, each contributing unique visual interpretations while retaining the core elements of the Rajasthani tradition.

The thematic range of Rajasthani painting was vast, covering religious narratives, royal court scenes, secular subjects, and portraiture. Among its most celebrated genres was the Ragamala painting, a visual representation of the Ragas and Raginis, the melodic frameworks of Indian classical music. Each painting personified a specific musical mode, often using symbolic settings, seasonal references, and emotional expressions to convey its mood.

Mewar Painting

Mewar painting stands as one of the most important

traditions of Indian miniature art from the 17th and 18th centuries.

Originating in the Hindu principality of Mewar in present-day Rajasthan, this

artwork represents a broader Rajasthani style, distinguished by its clarity,

warmth, and deeply expressive quality. While religious subjects dominated much

of the work, portraiture and depictions of the ruler’s life became increasingly

prominent. These portraits not only celebrated royal authority but also served

as a visual record of the courtly culture of Mewar.

Mewar paintings are celebrated for their simple yet

brilliant color palette and their direct emotional impact. The compositions are

often straightforward, yet they convey a striking sense of vitality and

devotion, making them immediately appealing to viewers. From the early 17th

century through around 1680, Mewar art retained a dynamic and highly expressive

character, with only slight stylistic variations over time. However, by the

late 17th century, Mughal influence began to leave a noticeable mark on the school,

bringing a greater emphasis on refined detailing and courtly sophistication.

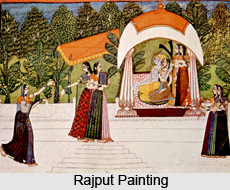

Rajput Paintings

Rajput paintings are a significant Indian painting which flourished during the medieval age in India. Various themes like that of the life of Lord Krishna, Ramayana, Mahabharata, picturesque landscapes, interior chambers of royal forts and `havelis` were popular. Rajput paintings thrived around the 18th century. The colours used were extracted from certain plants, conch shells and some minerals. Miniature Paintings were widely painted under this particular style of painting. Sometimes, extracts from processed silver, gold and precious stones were also employed in these paintings.

Mughal Paintings

Mughal paintings developed during the regime of the Mughal

dynasty which can be traced from the 16th to 19th century.

Like Rajput Paintings, Mughal paintings also favoured miniature paintings.

These creations were a combination of Persian, Islamic and Indian styles. Some

of the most reputed painters whose paintings blossomed during this age are

Miskin, Daswant, Bishandas, Ustad Mansur, Mir Sayyad Ali, Basawan, Govardhan, Lal

and many others. The paintings were used as book illustrations and also as

singular albums. Mughal-styled paintings are practiced even today by a few

talented artisans based in Jaipur, Rajasthan.

This art have been passed between several generations. Said Uddin and Rafi

Uddin are among the few rare Mughal style painters in the present times.

Tanjore Paintings

Tanjore paintings are believed to have born around the ninth century in the state of Tamil Nadu during the rule of the Chola dynasty. Hindu mythology and religion were the main themes used in Tanjore paintings. This type of painting is indigenous to Tanjore town, Tamil Nadu. It is said that Tanjore paintings originated as early ninth century, during the rule of the Chola kings. Tanjore paintings were characterised by bright colours and emphasis on intricate details of painting.

Bundi Paintings

Bundi school of painting emerged around 1625 CE. This art

form is celebrated for its vibrant colors, lyrical compositions, and strong

narrative appeal. One of the earliest known examples is a depiction of Bhairavi

Ragini housed in the Allahabad Museum. A central theme in Bundi painting is the

life of Krishna, often illustrated with warmth, humor, and devotion. Bundi

paintings are instantly recognizable for their glowing color palette such as

golden hues for the rising sun, crimson-red horizons, and lush greens for

overlapping, semi-naturalistic trees. While rooted in the Rajput tradition,

this artwork also reveals a Mughal influence, particularly in the fine,

expressive drawing of faces and the naturalistic rendering of vegetation. A

unique feature of many Bundi works is the placement of text, often inscribed in

black against a yellow background at the top of the painting—combining literary

and visual storytelling in perfect harmony.

Malwa Paintings

Malwa painting flourished between 1600 and 1700 CE, standing

as a distinctive example of the artistic traditions nurtured in the Hindu

Rajput courts of Central India. Unlike other Rajasthani schools, which

developed within clearly defined kingdoms and courtly boundaries, Malwa

painting cannot be tied to a single geographic center. Instead, it reflects the

cultural vibrancy of a broad Central Indian region, where its style evolved and

thrived before fading away towards the end of the 17th century. Malwa paintings

are instantly recognizable for their rigidly flat compositions and bold use of

dark backgrounds, often in deep black or chocolate brown. Figures are placed

against solid blocks of bright color, while architectural elements are rendered

in vivid, contrasting hues. The style possesses an undeniable primitive charm,

with a childlike simplicity that adds to its visual appeal.

Kangra Paintings

Kangra painting is one of the most celebrated traditions of Pahari art,

renowned for its elegance, naturalism, and lyrical beauty. It takes its name

from the princely state of Kangra, where Raja Sansar Chand played a significant

role in fostering its growth. While several artists contributed to its

development, the Nainsukh family is most prominently credited with shaping the

signature style that defined Kangra painting.

By the early 19th century, elements of the Kangra style began to spread beyond the hills, as some Pahari painters found patronage under Maharaja Ranjit Singh and the Sikh nobility in Punjab. This gave rise to a modified Kangra style, which retained its core aesthetic but incorporated regional influences, continuing well into the mid-19th century.

The Kangra repertoire was rich in religious, romantic, and literary themes, with some of its most celebrated works illustrating the Bhagavata Purana, Gita Govinda, Nala Damayanti, Bihari Satsai, Ragamala, and Baramasa. These paintings often combined storytelling with exquisite detail, creating works that were as visually captivating as they were culturally significant.

Kangra paintings are distinguished by their delicate and

refined drawing, naturalistic treatment of landscapes, and an overall serene

poetic quality. Of all Indian painting traditions, Kangra is often regarded as

the most romantic and lyrical, capturing a sense of grace and emotional depth.

Basholi Painting

Basholi painting, a remarkable branch of Pahari art, flourished in the 17th century within the princely state of Basholi, in the Jammu region of northern India. Distinguished by its striking color palette, dynamic compositions, and elaborate ornamentation, this art form became renowned for its expressive and spiritual depth.

The themes of Basholi paintings often draw from Hindu

mythology, with a special emphasis on the tender and divine love stories of Radha and Krishna. Artists

skillfully combined vivid hues with meticulous detailing, creating works that were

both visually captivating and emotionally resonant. As a pioneering school

within the larger Pahari tradition, Basholi painting left a lasting imprint on

medieval Indian art.

Deccani Paintings

Deccani painting developed in the flourishing Muslim capitals of the Deccan sultanates, successor states that emerged after the dissolution of the Bahmani Sultanate around 1520 CE. The key centers of this tradition included Bijapur, Golkonda, Ahmadnagar, Bidar, and Berar. Its golden period extended from the late 16th century to the mid-17th century, with a later revival in the mid-18th century, when Hyderabad became the principal hub of artistic production.

Deccani painting distinguished itself from the contemporary Mughal art of the north through its brilliance of color, sophisticated compositions, and an unmistakable aura of luxurious opulence. Deccani style leans towards ornamentation and elegance. Figures in Deccani art are notable for their tall, slender proportions, small heads, and distinctive drapery, often depicted in richly patterned saris. Faces are shown in three-quarter view, a departure from the predominantly profile-based Mughal approach, though sometimes lacking in detailed modeling.

Architecture in these paintings is represented in flat, screen-like panels, emphasizing decorative beauty over realistic perspective. While royal portraits were a common theme, they did not aim to replicate the Mughal focus on strict likeness, instead favoring an idealized portrayal that highlighted splendor and regality. Drawing from Persian, Turkish, and indigenous Indian influences, this style produced artworks that stood apart in both technique and spirit, leaving a rich legacy in the history of medieval Indian art.

Medieval Indian paintings utilized

a unique blend of Indian and Persian painting styles which involved bright

colours, abstract motifs and worldly subject matters. Scenes inside courts or

palaces, religious deities, etc. were common in these paintings.