Introduction

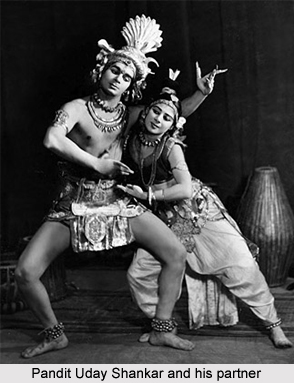

Pandit Uday Shankar was born on December 8, 1900 and became a world-renowned classical dancer and choreographer in India. Vishnudharmottarapurana mentions Vina tu nrtta sastrena chitrasutram sudurvidam- without the knowledge of dance the art of painting is an unattainable ideal. Uday Shankar, obviously was well acquainted with this inter-relationship and inter-dependence of arts instinctively. In 1923, when the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, asked him to fashion dance with Indian themes, he choreographed Krishna and Radha possibly in an imaginative manner. He aligned Anna Pavlova, the greatest ballerina of the world, and started his grand sojourn of dance, looking back was not destined and rising the ladder of fame was a self willed affair. From painting to dancing he made a smooth transition. It was his graceful grandeur that made Indian a world event in the domain of dance. Liberating himself from imitative culture he transgressed the known world of cultural dance laying emphasis on seeking the essence of the cultural legacy giving it a distinct Indian identity.

Pandit Uday Shankar was born on December 8, 1900 and became a world-renowned classical dancer and choreographer in India. Vishnudharmottarapurana mentions Vina tu nrtta sastrena chitrasutram sudurvidam- without the knowledge of dance the art of painting is an unattainable ideal. Uday Shankar, obviously was well acquainted with this inter-relationship and inter-dependence of arts instinctively. In 1923, when the Russian ballerina Anna Pavlova, asked him to fashion dance with Indian themes, he choreographed Krishna and Radha possibly in an imaginative manner. He aligned Anna Pavlova, the greatest ballerina of the world, and started his grand sojourn of dance, looking back was not destined and rising the ladder of fame was a self willed affair. From painting to dancing he made a smooth transition. It was his graceful grandeur that made Indian a world event in the domain of dance. Liberating himself from imitative culture he transgressed the known world of cultural dance laying emphasis on seeking the essence of the cultural legacy giving it a distinct Indian identity.

Early Life of Pandit Uday Shankar

Udaipur, a colorful town in Rajasthan happens to the hometown of an aristocratic Bengali family, where Pandit Uday Shankar was born. The ancestors of Pandit Uday Shankar belonged to Narail (in modern-day Bangladesh). Pandit Uday Shankar acquired the formal training in the art in Bombay, while he studied at the Royal College of Art in London. From his very adolescence he was conspicuously interested in magic, handling camera music stage performance of various sorts. Uday Shankar`s father made himself comfortable as his mentor and advisor; he inhabited a world of Sanskrit scholarship and Indian princely states. Uday Shankar, a Bengali Brahmin, was raised in a village near Varanasi and in the princely state of Jhalawar, where his father held a series of official posts in this small Rajasthani kingdom. His education continued in Mumbai and in London, where he went to join his father in 1920. So when he sailed back to India at age of 30, after ten consecutive years in Europe and America, he had to rediscover his land. After a year he left India again, taking his family to Paris, the base for his first dance company of Indian artists, co-founded with Swiss sculptress Alice Boner.

Career of Pandit Uday Shankar

The creative heads noticed Pandit Uday Shankar when he created wonderful ballets based on Hindu themes like Radha-Krishna, Hindu weddings and other oriental themes for Anna. He loved to fuse the dance forms and make a blend of Eastern and Western. During the 1930s, Uday travelled across the western world along with his own troupe. His version of western theatrical techniques to Indian dance made his art massively popular both in India and the West. His brother Ravi Shankar helped him to popularize Indian classical music in the West.

While Pandit Uday Shankar was enrolled in the Royal College of Art in London, he choreographed two ballads of which one was based on Hindu mythology ("Krishna and Radha") and the other on Hindu society ("A Hindu Wedding"). These two ballads were showcased at the Covent Garden. During this time he came in contact with the famous Russian ballerina, Anna Pavlova. He worked with her and she taught him all the exquisite ballet movements, which he widely incorporated in his upcoming creations. The graceful movement of ballet dancers impressed him and he stated to incorporate ballet movements in Indian dance for the first time. Pandit Uday Shankarwas credited to be engendering a "new kind" of Indian dance. Pandit Uday Shankar`s dances were deep rooted in Hindu mythology and he extensively used classical raga music in his choreography Though without any formal training in any of the Indian classical dance forms, he formulated his own troupe in 1929 with financial assistance from Alice Boner-the Swiss Sculptress and indulged in tour amidst Indian extensively, and in Europe between 1932 and the 1960s acknowledging himself about traditional, classical and a confounding variety of folk dances, amassing a variety of Indian musical instruments and bona fide costumes. The result was astounding. The audience was breathtakingly mesmerized and bewitched witnessing his dance, the showmanship, the visual offering of phantasmagoria. His years with Anna Pavlova as an apprentice refracted their earned glory.

The Europeans admired his "new style" of dancing; they had an idea of Indian dances to be rigid, stiff and stereotyped, but the new style by Pandit Uday Shankar kept everyone thrilled about this art. It took a while before Indians started appreciating Pandit Uday Shankar`s "new style," which was hybrid in nature. The experienced personalities in the arena of dancing were not encouraged by Uday Shankar`s "new style" of dance.

The Europeans admired his "new style" of dancing; they had an idea of Indian dances to be rigid, stiff and stereotyped, but the new style by Pandit Uday Shankar kept everyone thrilled about this art. It took a while before Indians started appreciating Pandit Uday Shankar`s "new style," which was hybrid in nature. The experienced personalities in the arena of dancing were not encouraged by Uday Shankar`s "new style" of dance.

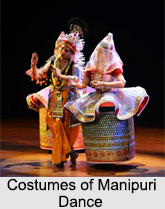

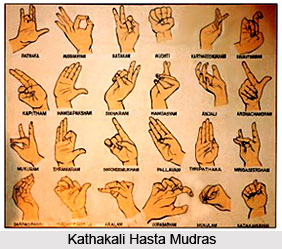

His Europe account informs, Uday Shankar had at the invitation of Elmhirst, who had been a right hand Gurudev Rabindranath Tagore in building Sriniketan, visited Dartington Hall, Totnes, Doven for a residency of six months in 1936. He even had the chance encounter with Michel Chekhov, the nephew of the Russian playwright Anton Chekhov, the German choreographer, Kurl Joos and another German Rudolf Laban who invented the dance notation. He ruefully observed the methodology of Michel Chekhov and incorporated the influences in his style. Uday Shankar drew inspiration from Dartington Hall, and accepted the suggestion of Elmhirst to establish a Centre for Dance in India. He chose Simtola, near Almora in the United Provinces and by 1940 started his famous Uday Shankar India Culture Centre. The Centre specialized in training the dancers in the art of creativity, improvisation, concentration and imagination. In the foothills of the Himalayas, where and invited Shankaran Nambudirei for teaching the dance forms like Kathakali, Kandappa Pillai for Bharatnatyam, Amobi Singh for Manipuri and Ustad Allauddin Khan for music. However, the center was closed during World War II but it was later reopened in Kolkata after the war in 1965. In Kolkata, the school was however renamed as Uday Shankar Center for Dance. Pandit Uday Shankar married his student, Amala in his late thirties. The studies in Uday Shankar Center for Dance taught an all-embracing performance curriculum that includes training in folk and classical dance, improvisation, costume design and even theatrical makeup. Pandit Uday Shankar established a relaxing institution in the hills of Kumaon, where he requested teachers from different genres to train his troupe in order to groom their bodies to a situation where they could create a varied, rich and modern dance vocabulary.

However, the young generation was overwhelmed by his style and innumerable students joined his school in Almora. Uday Shankar Center for Dance was a waterhole for many upcoming and interested dancers. Many graduates of the school possessing the talent of dancing enrolled into this school. The famous Bombay film director, Guru Dutt had attended Uday Shankar Center for Dance. The famous classical singer, Srimati Laxmi Shankar also attended this school at Almora. She was advised by Ravi Shankar to change her career from dancing to singing and she later married Rajendra Shankar, the younger brother of Pandit Uday Shankar.

Personal Life of Pandit Uday Shankar

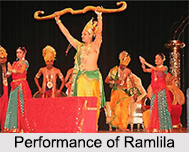

Pandit Uday Shankar had married Amala Shankar and they had a son Ananda Shankar and a daughter Mamata Shankar. Ananda Shankar grew up to be a popular musician and music composer who received training from Dr. Lalmani Misra rather than his uncle, Ravi Shankar. Pandit Uday Shankar`s only daughter Mamata Shankar grew up to be one of the most charming and talented dancers of India alike her parents and is also a noted actress. She has acted in several prominent films by Satyajit Ray and Mrinal Sen. Pandit Uday Shankar also made a film on dance entitled `Kalpana` which apart from recording his choreographic creations managed to reach out to larger audience. He dealt with the film medium efficiently. Kalpana, a visual treat is a record of the created reality of his artistic extravaganza where he experimented in shadow play and spectacle carrying a juxtaposition of the stage and the screen in his unique Shankar Scope. However, his followers and predecessors created a niche of their own, keeping intact the form. Foremost amongst them was Shanti Bardhan who gave us immortal Ramayana with human beings performing like puppets. He also introduced the fable of Panchatantra creating movements of the birds and the animals.

Awards for Pandit Uday Shankar

He was awarded Padma Vibhushan by the Government of India and the Desikottama by the Visva-Bharati University.

Uday Shankar - The Idol

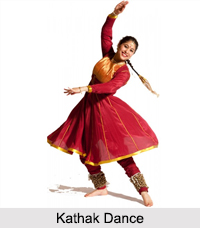

Pandit Uday Shankar`s birth centenary was held in India in the year 2000. Well-written articles were seen in almost every newspaper throughout India. A well planned photo exhibition on the occasion of Uday Shankar`s centenary rendered it possible to see various facets of his talented genius. Uday Shankar had, with his doughty creativity shown originality in his approach towards choreography. His icon is the epitome of inspiration to the generations of dancers who are on a perpetual quest to seek new directions. For him imitation was equal to death. By remembering him we pay homage to one who brought to Indian dance great relevance and respect. Modern Dance in India has a relatively short history and Pandit Uday Shankar was widely accepted as the Father of Modern Indian Dance. This great dancer had a wide vision, and appreciated the wonderful diversity and capacity of expression afforded by the various classical and folk dances in any country he visited. His search for a delicate expression led him to integrate special dance styles, such as Bharatnatyam and Kathakali into his choreographic productions.

Pandit Uday Shankar was the dancer par excellence and was referred as the renaissance dancer who updated the stylized temple dance of India and popularized the art form all over the Western lands. Bulbul Chowdhury is Bangladesh`s one-time famous dancer and a student in Pandit Uday Shankar`s school of dancing during the 1940s. Pandit Uday Shankar was a romantic as well as a wonderful showman. He was often called as the catalyst in the renaissance of interest in Indian arts during the 1930s and `40s.

The creative dance movement in India unanimously owes its growth to Pandit Uday Shankar. With his success during the 1930s, a unique movement of revival of classical dances had begun. The last decades of Shankar`s life were a complex journey of success and struggle, his fame eclipsed by national promotion of classical dance as evidence of an ancient heritage and thus a place for India among the civilized nations of the world. The essence of various traditions and techniques could be seen in Pandit Uday Shankar`s dance dramas that succeeded in presenting an integrated composition. He exclusively used only Indian musical instruments during his dance dramas. The superb showmanship and perfection of Pandit Uday Shankar cast a spell on his audience, all over the world. In true sense he is the harbinger of Indian artistic culture, a title accredited to him by Tagore.

Contributions of Uday Shankar

Contribution of Uday Shankar to the Indian classical dance has been immense. He modernised and internationalized the Indian classical dance and his legacy is now being followed by people around the world. Pandit Uday Shankar came across Anna Pavlova, a Russian Ballerina; in one of the events organized by his father where he was suppose to dance as well. Though he did not posses any formal training in the classical dance, but he was exposed to folk dance and Indian classical dance, as well as ballet. With his extensive knowledge, familiarity and awareness of Indian dance and his association with European and Indian musician and dancers helped him immensely in order to create number of productions and dance concepts.

Contribution of Uday Shankar to the Indian classical dance has been immense. He modernised and internationalized the Indian classical dance and his legacy is now being followed by people around the world. Pandit Uday Shankar came across Anna Pavlova, a Russian Ballerina; in one of the events organized by his father where he was suppose to dance as well. Though he did not posses any formal training in the classical dance, but he was exposed to folk dance and Indian classical dance, as well as ballet. With his extensive knowledge, familiarity and awareness of Indian dance and his association with European and Indian musician and dancers helped him immensely in order to create number of productions and dance concepts.

Uday Shankar`s Contribution before Independence era

Uday Shankar`s major contributions arrived during the epoch preceding Indian independence at the fag end of Colonial supremacy, when Gandhi was in a congregation with the British, and Indians were vigorously nationalistic, provoked and avowed by the Congress Party. The renaissance phase in Indian dance, which began in the late 1920s, and flowered in the 1930s, irretrievably adds to his career graph.

Shankar presented his repertoire to Indian audiences during this tour, and captivated spectators who had seen no other stage dance in India. He took as his guru the Kathakali dance-drama master, Shankaran Namboodiri, he promoted classical dance in his Almora Culture Centre, with four gurus presiding over Kathakali, Bharatnatyam, Manipuri, and Hindustani Sangeet (North Indian Classical Music). But by 1935 during his second tour in India, a few Indians had seen the devadasi dance renamed as Bharatnatyam. They questioned whether Shankar`s dance was Indian, were authentic, were classical, and should be called `ballet.` Nationalism and colonialism are not mere external contexts for Shankar`s dance and success; they are the context in the midst of which he performed, was reviewed, met his patrons, and created his repertoire

Uday Shankar`s Contribution after Independence

Three years after Indian independence in 1947, when the national academy of performing arts, Sangeet Natak Akademi, reconceptualized India`s arts, the few classical dance styles and the myriad Indian folk dances became their focus. Uday Shankar`s creative dance was not in the picture, though he had made India his permanent base since 1938. In the new nation that echoed unity in diversity infused cultural policy as well as politics. Dance was to be either classical or folk, and there was no room for new traditions, such as that of Shankar style dance. Pre-independence nationalism was transmuted, in the new nation, into affirmation of its ancient heritage.

Despite this preference, Shankar`s new company, continuing his inventive choreographies and modernist presentations, toured in China, the United States, and Europe, straining financially in the post-war epoch The Uday Shankar Company persists today, based in Calcutta and led by his partner and widow, Amala Shankar. He even included Gandhi`s social philosophy of unity and de casteism. The pieces thus proffered a new nationalistic energy for progress, following a decade of religio-mythological ballets and light folk-based divertissements. After independence Shankar took the Buddha as a theme, and later he experimented in his Shankarscope production with mixed media of film and dance. Well aware that dance was for its own times and for particular audiences, Shankar wanted to try new ideas, explore new media, and consider contemporary themes. This evolutionary perspective is continued today as Indian dancers and choreographers turn to new dance, and as some recognize Shankar`s contribution to their modern art.

But strikingly, in the 1980s and l990s, there has been a sea change, and it neither obliterates nor replaces the suspicion and smug dismissal of Uday Shankar which characterized his latter years and the difficult decades which followed. This context is as much a part of his genius as is his choreography, his costumes and lights, his timing and rhythmic sense, his stage presence, and his reputation. There are, it turns out, not one, not two, not even three, but four or five twists in the Uday Shankar pathway, and they are integral to any analysis of his works, as well as to his continuing presence in the world of Indian dance and modern ideas of choreography in India.

`New directions in Indian dance` has become the guiding text for the current turn, which dates from the 1980s. Bharatanatyam, in explorations merging Indian forms such as yoga and chhau and the martial art of kalaripayyatt, and in experimental fusions of western and Indian dance, mainly outside of India in the United States and Canada, England, Germany, France as well as Japan and Australia. So choreographers, dancers, critics and presenters of new dance are also potential readers of Uday Shankar`s biography, and need to have a sense of how Shankar created and choreographed his `new dance for the 30s`, which was seen then as `authentic Indian dance` by Europeans, and many Indians, at least at first.

Uday Shankar`s Contribution in breaking the concept of male is not for dancing

Thus, the history of European and Indian knowledge of India`s dance forms becomes a site of controversy in the biography of Uday Shankar. That is, European experiences of `oriental dance`, from the often-seen ballets of the Romantic era, present the oriental dancer as a bayadere, related to the odalisque of eastern harems: a veiled, mysterious, sexually unexplored figure, rather more like the sylphs than the tawaifs and devadasis they were. `Orientalism` wasn`t based on subtle or sharp distinctions between the cultures of the East; rather these cultures were grouped together as `other`, and seen as dark, mysterious, spiritual, exotic, erotic and altogether enticing. Male dancers from the East were few and far between. As recent writings have suggested, such masculine presences did not fulfill the Orientals strategy of using females as symbols for submission to patriarchy and colonialism, a theme which preoccupied, consciously and subconsciously, much of European arts in the l9th and early 20th centuries.

In the 1930s the advent of a Male Oriental Dancer was quite a revelation. Suddenly there was an exotic oriental dark (but not too dark) dancer, who appealed to women. In the 1930s, while touring Uday Shankar and his company in the United States, Russian impresario Sol Hurok noted that Shankar`s audiences were filled with women, who adored him. Shankar`s major patrons were women, not surprisingly. His company, until 1935, had no other male dancers with his impact, until he brought in Madhavan, trained in the south Indian dance-drama form of Kathakali, to create and present his own solos as a tribal or warrior. But Shankar remained the sole male form of the divine, the god, on stage, in his productions.

In the realm of European and American images of the exotic oriental, Shankar`s appearance on the Paris dance scene in the 1930s, and his huge success in France and Germany, as well as America, paralleled a fascination with Eastern spirituality and philosophy. The Theosophical Society was gaining followers in India and abroad. During the time that Uday Shankar`s father, Shyam Shankar Chaudhury, was a Sanskrit scholar in Varanasi at the turn of the century, he became a follower of Theosophical Society leader Annie Besant. Uday`s main partner in his first company was Simkie, whose mother was a member of the Paris branch of the Theosophical Society. In addition, a number of European women, of various descent and experience though none of them Indian, had promoted themselves to the Paris public as Indian dancers. Probably the most famous-and later notorious-was Mata Hari, who presented herself as a devotee of Shiva at the Musee Guimet in 1905. So when Uday Shankar appeared as an authentic Indian, but an accessible one, able to enter the demi-monde and other Paris society as a Brahmin, son of an Indian princely state`s Foreign Minister, and a former partner of prima ballerina Anna Pavlova, this was an entirely different presence, with legitimizing credentials in place. One of the issues which I have been researching is the fact that Uday Shankar, in 1924, could not succeed in London, despite these connections, but did find support and avenues for this dance in Paris.

Other Contributions of Pandit Uday Shankar

Uday Shankar, along with Slice Boner (Swiss sculptor), in 1931, created the first Indian dance company in Paris and subsequently embarked on an international tour lasting almost for seven years. Apart from that he worked with many other notable people as well in sync with Vishnudass Shirali and Tami Baran to find original ways of using music to accompany his new language of movement. His love, fascination and curiosity about movement, dance, music, costumes of various folk, classical and marital forms of various parts of India actually helped him in setting up `Uday Shankar India Cultural Centre` near Almora in Uttarakhand.

He invited Thottam Shankaran Namboodiri for Kathakali, Ustad Allaudin Khan for music, Ambi Singh for Manipuri and Kandappa Pillai for Bharatanatyam. He actually formulated an extensive training program that incorporated the learning of numerous physical and performance traditions, creativeness, sensitisation exercises, visual art, music, group activities and even psychology. The centre unfortunately closed down within four years due to unavailability of finances.

His solo performances on Lord Shiva, Lord Indra and Karthikeya were well acclaimed works. He also produced an important film called Kalpana which has influenced film in India.