Introduction

Natyashastra is an ancient form of Indian theatre with details performing arts, encompassing theatre, dance and music. It was written during the period between 200 BC and 200 AD in classical India and is traditionally attributed to the Sage Bharata. It is elaborate of all treatises on dramatic criticism and acting ever written in any language and is regarded as the oldest surviving text on stagecraft in the world. Bharata in his Natyashastra demonstrates every facet of Indian drama whilst covering areas like music, stage-design, make up, dance and virtually every aspect of stagecraft. With its kaleidoscopic approach, with its wider scope Natyashastra has offered a remarkable dimension to growth and development of Indian classical music, Indian classical dances, drama and art. Natyashastra indeed laid the cornerstone of the fine arts in India.

Natyashastra is an ancient form of Indian theatre with details performing arts, encompassing theatre, dance and music. It was written during the period between 200 BC and 200 AD in classical India and is traditionally attributed to the Sage Bharata. It is elaborate of all treatises on dramatic criticism and acting ever written in any language and is regarded as the oldest surviving text on stagecraft in the world. Bharata in his Natyashastra demonstrates every facet of Indian drama whilst covering areas like music, stage-design, make up, dance and virtually every aspect of stagecraft. With its kaleidoscopic approach, with its wider scope Natyashastra has offered a remarkable dimension to growth and development of Indian classical music, Indian classical dances, drama and art. Natyashastra indeed laid the cornerstone of the fine arts in India.

Text of Natyashastra

Natyashastra of Bharata Muni contains about five thousand six hundred verses. The commentaries on the Natyashastra are known, dating from the sixth or seventh centuries. The earliest surviving one is the Abhinavabharati by Abhinava Gupta. It was followed by works of writers such as Saradatanaya of twelfth-thirteenth century, Sarngadeva of thirteenth century, and Kallinatha of sixteenth century. However the abhinavabharati is regarded as the most authoritative commentary on Natyashastra as Abhinavagupta provides not only his own illuminating interpretation of the Natyashastra, but wide information about pre-Bharata traditions as well as varied interpretations of the text offered by his predecessors.

Background of Natyashastra

Written in Sanskrit, the vast treatise consists of six thousand sutras. The Natyashastra has been divided into thirty six chapters, sometimes into thirty seven or thirty eight due to further divergence of a chapter or chapters. The background of Natyashastra is framed in a situation where a number of munis approach Bharata to know about the secrets of Natyaveda. The answer to this question comprises the rest of the book. Quite ideally therefore narratives, symbols and dialogues are used in the methodology of Natyashastra.

Contents of Natyashastra

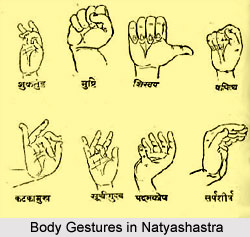

A mere perusal of the contents of Natyashastra will depict the variety of the topics discussed therein. The principal theme is the dramatic art which concerns the producers of the plays as well as those who compose them, the playwrights. Bharata wanted the plays to be a Drisya Kavya that can be successfully and profitably represented on the stage. The dramatic theory as well as practice has been elaborately dealt with in the text. Hence, manual gestures, facial expressions, poetics, music with all ramifications whether vocal or instrumental, prosody, some points of grammar, costumes, ornaments, setting up of the scenes with appropriate background etc. have been methodically dealt with. The author has treated the subject matter so very analytically as not to hesitate to repeat the things mentioned earlier in order to be more specific.

A mere perusal of the contents of Natyashastra will depict the variety of the topics discussed therein. The principal theme is the dramatic art which concerns the producers of the plays as well as those who compose them, the playwrights. Bharata wanted the plays to be a Drisya Kavya that can be successfully and profitably represented on the stage. The dramatic theory as well as practice has been elaborately dealt with in the text. Hence, manual gestures, facial expressions, poetics, music with all ramifications whether vocal or instrumental, prosody, some points of grammar, costumes, ornaments, setting up of the scenes with appropriate background etc. have been methodically dealt with. The author has treated the subject matter so very analytically as not to hesitate to repeat the things mentioned earlier in order to be more specific.

Cultural Projection in Natyashastra

Prakrita and allied native languages are meticulously dealt with by means of examples in the Natyashastra. References have been made to the languages of ancient tribes such as Barbaras, Kiratas, Andhras, Dravidas, Sabaras, Candalar etc. Beautiful verses of very fine literary excellence have been given by way of examples, while dealing with Dhruva songs, metres etc. In many of these verses the innate charm divested of all the artifices and linguistic of the later classical age are found. Rasas, Bhavas, Alankaras etc. are portrayed well. Dance is inseparable from drama and Bharata has done full justice to it. The various Abhinayas mentioned in the text have been portrayed by mural paintings, sculpture, architecture etc. in the temples. Various crafts are brought into play to create a suitable background in the stage in different scenes. Natyashastra gives detailed directions about the dressing material, modes of wearing the garments and jewellery, articles to be used by the different characters in a play in accordance with their social status, profession, the cultural practice etc.

Natyashastra mentions mythological figures starting from the lowest stratum such as the Uragas, Patangas, Bhutas, Raksasa, Asuras etc. and also the gods and goddesses of the Hindu Pantheon viz; Danavas, Guhyakas, Kstadikpalakas, Gandharvas Apsaras, Asvins, Manmatha, Rudra, Visve Devas, Brhaspali Narada, Tumburu, Rishis, Mantradrastras, Lord Brahma, Lord Vishnu, Lord Shiva, Goddess Lakshmi, Chandi Chandika, Sarasvati etc. There are references to cities and rural regions such as Anga, Antagiri, Andhra, Avarta, Kharta, Anarta, Usinara, Odra Kalinga, Kasmira, Tamralipta, Tosala, Tripura, Dakshinapatha, Dramida, Nepala, Pulindabhumi etc. Rivers and mountains such as Sindhu, Ganga, Malaya, Sahya, Himalaya and Vindhya mountain range finds place in the Natyashastra. Natyashastra opens with the origin of theatre, beginning with inquiries made by Bharata`s pupils, which he answers by narrating the myth of its source in Brahma. Natyashastra consists of four elements namely pathya or text, including the art of recitation and rendition in performance taken from the Rig Veda. The other one is gita or songs, including instrumental music from the Sama Veda, abhinaya or acting, the technique of expressing the poetic meaning of the text and communicating it to the spectator from the Yajur Veda, and rasa or aesthetic experience from the Atharva Veda.

Chapters of Natyashastra

With well knit chapters, Natyashastra, cover every aspect of Indian art and drama. From issues of literary construction, to the structure of the stage or mandapa, from a detailed analysis of musical scales and movements, to an analysis of dance forms and their impacts on the viewers, Natyashastra covers every possible facet in detail.

As an audio visual form, Natyashastra mirrors all the arts and crafts, higher knowledge, learning, sciences, yoga, and conduct. Its purpose is to entertain as well as educate. Bharata was an ideal theatre artist and is gifted with restraint as well as vision. He understood the fact that performance is a collective activity that requires a group of trained people, knit in a familial bond and has best portrayed this understanding in the first chapter of his treatise, Natyashastra. In the first chapter Bharata therefore talks about the response and involvement of the spectator in drama. The spectators come from all classes of society without any distinction, but are expected to be at least minimally initiated into the appreciation of theatre. This is because of the fact that they may respond properly to the art as an empathetic sahridaya. Theatre flourishes in a peaceful environment and requires a state free from hindrances. The first chapter ends emphasising the significance and importance of drama in attaining the joy, peace, and goals of life, and recommending the worship of the presiding deities of theatre and the auditorium.

The second chapter lays down the norms for theatre architecture or the prekshagriha i.e. auditorium. This also protects the performance from all obstacles caused by adverse nature, malevolent spirits, animals, and men. It describes the medium sized rectangular space as ideal for audibility and visibility, apparently holding about four hundred spectators. Bharata also prescribes smaller and larger structures, respectively half and double this size, and square and triangular halls. Bharata`s model was an ideal intimate theatre, considering the subtle abhinaya of the eyes and other facial expressions which he described in the second chapter of Natyashastra.

The second chapter lays down the norms for theatre architecture or the prekshagriha i.e. auditorium. This also protects the performance from all obstacles caused by adverse nature, malevolent spirits, animals, and men. It describes the medium sized rectangular space as ideal for audibility and visibility, apparently holding about four hundred spectators. Bharata also prescribes smaller and larger structures, respectively half and double this size, and square and triangular halls. Bharata`s model was an ideal intimate theatre, considering the subtle abhinaya of the eyes and other facial expressions which he described in the second chapter of Natyashastra.

The third chapter describes an elaborate puja at home for the gods and goddesses protecting the auditorium, and prescribes rituals to consecrate the space. Chapter four of the Natyashastra begins with the story of a production of Amritamanthana i.e. `Churning of the Nectar`, a samavakara performed according to Brahma`s instructions on the peaks of Kailasa, witnessed by Lord Shiva. After some time, a dima titled Tripumdaha or `Burning of the Three Cities` is staged, relating Shiva`s exploits. Shiva asks Bharata to incorporate tandava dance in the Purvaranga preliminaries and directs his attendant Tandu to teach Bharata. Tandu explains the components of tandava, the categories of its movements, and their composition in chorographical patterns. These form the pure dance movements required for the worship of the gods and the rituals. This chapter also lays the foundation of angika abhinaya or physical acting developed in later chapters. The fifth chapter however details the elements of Purvaranga. Thus the first five chapters are structurally integrated to the rest of the text

The sixth and seventh chapters deal with the fundamental emotional notions and aesthetics of rasa and bhava. The Bhavas, which include the vibhavas, are communicated to spectators through abhinaya, especially angika language. Therefore it receives elaborate treatment in the chapter eight to twelve. The chapters like 8, 9, 10, 11 and 12 thus codify body language based on a definite semiotics. Movement requires well-defined blocking, so immediately afterwards the Natyashastra lays down the principle of kakshyavibhaga in the thirteenth chapter. The extremely flexible and easy principle of establishing space on stage and altering it through parikramana or circumambulation is a unique characteristic of traditional Indian theatre and dance and are subtly dealt in the next chapters of Natyashastra.

Chapter eighteen discusses the ten major Rupakas, or forms of drama and natika, a variety of uparupaka. The next chapter analyses the structure of drama as well as the inclusion of lasyangas or components of feminine dance derived from popular dance and recitative forms in theatre. Chapter twenty gives an elaborate account of the vrittis. Chapter twenty one deals with aharya abhinaya and covers make up, costume, properties, masks, and minimal stage decor. Chapter twenty two begins with samanya or `common` abhinaya, which compounds the four elements of abhinaya harmoniously. It discusses other aspects of production too, which may be viewed as `inner`, adhering to prescribed norms and systematic training, and `outer` or done freely outside such a regimen. This chapter ends with an analysis of women`s dispositions, particularly pertaining to love and terms of address, while the following chapter twenty three deals with male qualities and patterns of sexual behaviour, as well as classification and stages of feminine youth. Chapter twenty four specifies the types of characters in Sanskrit theatre. Chapter twenty five deals with chitrabhinaya i.e. `pictured acting` especially meant for delineating the environment occurring as a stimulant or uddipana vibhava of different bhavas. It also defines the specific ways of expressing different objects and states, and the use of gestures, postures, gaits, walking, and theatrical conventions. The next two chapters present the nature of dramatis personae, the principles of make-up, and speak about the success and philosophy of performance.

The chapter twenty seven deals with music employed in theatre. Chapter twenty eight covers jati or melodic types or matrices, sruti or micro-intervals, svara or notes, grama or scales, and murcchana or modes or ragas. Chapter twenty nine describes stringed instruments like the vina and distinguishes between vocal and instrumental music, further dividing vocal into two types, varna or `colour`, only syllabics and giti or `song`, with lyrics. Chapter thirty describes wind instruments like the flute and ways of playing it. Chapter thirty one deals with; cymbals and tala, rhythm and metrical cycles! Chapter thirty two defines dhruva songs, their specific employment, forms, and illustrations. Chapter thirty three lists the qualities and defects of vocalists and instrumentalists. The next chapter relates to the origin and nature of drums.

The chapter twenty seven deals with music employed in theatre. Chapter twenty eight covers jati or melodic types or matrices, sruti or micro-intervals, svara or notes, grama or scales, and murcchana or modes or ragas. Chapter twenty nine describes stringed instruments like the vina and distinguishes between vocal and instrumental music, further dividing vocal into two types, varna or `colour`, only syllabics and giti or `song`, with lyrics. Chapter thirty describes wind instruments like the flute and ways of playing it. Chapter thirty one deals with; cymbals and tala, rhythm and metrical cycles! Chapter thirty two defines dhruva songs, their specific employment, forms, and illustrations. Chapter thirty three lists the qualities and defects of vocalists and instrumentalists. The next chapter relates to the origin and nature of drums.

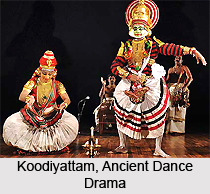

The concluding two chapters lay down the principles for distributing roles and the qualifications for members of the troupe. Bharata narrates the story of his sons, who ridiculed the sages and were cursed. He instructs them to expiate their sin, so that they attain their lost glory again. He returns to the performance in heaven where Indra enacts Nahusha, and finally to the descent of theatre on earth. Bharata ends his Natyashastra by stating the glory of theatre. Natyashastra remained an important text in the fine arts for many centuries whilst influencing much of the terminology and structure of Indian classical dance and music. For about two thousand years the Natyashastra has inspired new texts and various regional traditions of theatre. Kutiyattam in Kerala is an extant Sanskrit form that imbibed and developed the theory and practice originating from the Natyashastra. The analysis of body forms and movements defined in Natyashastra also influenced Indian sculpture and the other visual arts in later centuries.

Theatre in Natyashastra

Bharata in his Natyashastra gives a detailed account regarding the various aspects of the theatre. The main features as described by Bharata were adhered to in later times. The most important topics dealt with in the Natyashastra are the measurements of the stage, interior decorations, green room, mattavaranis, Rangasirsa, Rangapitha and the seating arrangements.

Measurements of Stage

According to the Natyashastra, the play-house as made ready for performance may be of three types, namely vikrista (rectangular), caturasra (square) and tryasra (triangular). The vikrista is jyestha, caturasra is madhya and tryasra is avara. The measurement is done in hastas. The Natyashastra states that the vikrista is one hundred and eight hastas, the caturasra is sixty four hastas and tryasra is of thirty two hastas. From the Natyashastra, it is found that the jyestha type is specially meant for gods, madhya for kings and avara for ordinary people. The measurement of the building of theatre was dependent upon the conception of hasta and danda. The smallest measure according to the Natyashastra is anu (atom). Eight anus make one raja, eight rajas one bala, eight balas one liksa, eight liksas one yuka, eight yukas one yava, eight yavas one angula, twenty four angulas one hasta and four hastas one danda. The measuring tape should be made of karpasa, vadara, valkala or munja and must have no joints. According to Bharata, while constructing a play-house, it is necessary that the soil should be first examined. It must be even, steady, hard and black or white. The whole field must be ploughed and bones, nails, skulls and such other things taken out.

The standard theatre is a rectangular building, sixty four cubits in length and thirty two cubits in breadth, marked out into two equal divisions, the auditorium and the stage. The stage is divided into two equal parts, the front and the rear, the latter being the green room. The front part is again divided into two equal parts. Of these two parts the one behind is the head of the stage (Rangasirsa) and the front part is the stage proper where the play is acted. On either sides of the stage proper, two mattavaranis, equal in measure to the stage, are constructed. The auditorium is 32×32 cubits, the front stage is 8×16 cubits, the back stage is 8×32 cubits and the green room is 16*32 cubits. The caturasra type of theatre is thirty two cubits in length and thirty two cubits in breadth. The whole field 32×32 cubits should be divided length wise and breadth wise into eight equal parts, thus making sixty four squares. The Rangapitha should be in the four inner squares. In this type the mattavaranis will be 8×8 cubits each and the Rangasirsa 8×8 cubits. The size of the green room is 4×32 cubits and that of the auditorium is 12×32 cubits. The tryasra theatre is in the form of an equilateral triangle. It is divided into eight parts on each side and from each dividing point lines are drawn parallel to those on the side of the equilateral triangle. Thus sixty four triangles are formed. The Rangapitha is built in the middle. Behind the Rangapitha is placed the Rangasirsa in five triangles and the green room in fifteen triangles. Each of the mattavaranis is constructed in eight triangles. The remaining triangles are reserved for the audience. The Natyashastra prescribes no exact measurement of the tryasra type theatre.

Rangapitha

The height of the theatres was dependent on the type of play that was to be performed. The theatre usually had the shape of a mountain cave and was constructed in two storeys with a few windows. The avibhumi was the higher and lower portions of the Rangapitha. From the Rangapitha, from where the seats for the audience commence to the exit, bhumis should be made, each one higher than the preceding one, the last having a height equal to the height of the Rangapitha, so that the rows of the spectators may not get in the way of one other`s view. The stage was often a double storeyed building. The upper storey of the theatre was used for the presentation of the dramatic actions of celestial regions and the lower one for that of the terrestrial ones. The terrace in the play Ratnavali suggests that the stage had an upper storey. According to the Natyashastra, the divisions of the stage should be made in the regular order and the divisions were known as kaksyas. When a change of scene was to be effected, it could be done through kaksyas.

Those who come in to the stage first are said to be inside the place of representation. Those who enter afterwards are said to be on the outer side of the place of representation.

Rangasirsa

The Rangasirsa is the back stage of the theatre. The Rangasirsa is built of six pieces of wood and furnished with two doors leading into the green room. It is smooth and even like a mirror and decorated with jewels. The in-between space is filled with very fine black earth, having the shine of a pure mirror and studded with emeralds, sapphires, corals and other valuable stones, arranged in a variety of designs on the four sides. The Rangasirsa is constructed with six planks. Portion of the back stage or the Rangasirsa, is reserved as a place of rest for actors, for maintaining the privacy of the entrance and exit and for purposes such as prompting, securing some stage effect and storing stage equipments. The Rangasirsa was of a level higher than the Rangapitha in the vikrista type of theatre and of the same level in the caturasra. The Rangapitha and the Rangasirsa were positioned in two different parts of the theatre as they were used for diverse purposes.

The Natyashastra prescribes that the musicians should sit in the Rangasirsa.

Nepathyagriha

The green room (nepathyagriha) is a part of the main building. Behind the curtain are the quarters of the actors {nepathyagriha). In the vikrista type of theatre the green room is 16×32 cubits and in the caturasra type it is 4×32 cubits. The green room is a moderately airy place to enable the several characters to attend to their costume and make up. The nepathyagriha is a place from where sounds are raised to indicate uproar and confusion; here also are uttered the voices of gods and other persons whose presence on the stage is not desirable. For example, in the play Ratnavali, the magician`s art which could not be shown on the stage and was described through uproar behind the scenes

Mattavaranis

The Natyashastra prescribes that on both the sides of the Rangapitha, two mattavaranis are to be constructed. A mattavaranis has four columns. The mattavaranis are one and a half cubit higher than the Rangapitha and were some special portions of the Rangapitha because action was performed on these mattavaranis. The mattavaranis could also be used as kaksyas.

Seating Arrangements

The Natyashastra states that, on the Rangapitha there must be ten columns strong enough to bear the burden of the mandapa. People of different castes were to sit at places indicated by columns of various colours. Brahmanas had the front seats indicated by a white column. Kshatriyas occupied seats indicated by a red column. Behind them sat Vaisyas and Sudras, the former to the north-east and the latter to the north-west, their seats being indicated by yellow and blue columns respectively. There were other columns too, perhaps, to provide accommodation those who were not incorporated in the four castes. Galleries were to be erected one behind the other. Seats in the auditorium were to be arranged in the form of a staircase to guarantee visibility. They were to be made of wood and bricks and were to be one and a half above the ground. The Natyashastra prescribes different places for the castes and for various strata of society, it is clear that the theatres, in ancient India though constructed as a temporary structure, were planned for the general public.

Doors and Roofs in Theatre

According to the Natyashastra, the vikrista theatre has two doors leading to the green room from the Rangasirsa. The players of musical instruments sat in between these doors. In the caturasra type a door leads to the Rangapitha. The first door is for people to enter the theatre and the second door is in front of the auditorium. In the tryasra type there is one door at the back of the Rangapitha and another in one corner for the entry of the audience. In the Natyashastra there is only one reference to theatres without roofs. But the theatres in which plays were performed must have had roofs. There are indications in the Natyashastra which prove the existence of roofs. In the section on arrangement of columns the Natyashastra says that the columns should be capable of supporting the roof.

Bharata`s description of theatres, their construction, size and shape, the position of the stage, orchestra and auditorium, indicates that theatres were of a permanent nature. Thus the Natyashastra gives an elaborate detail on the different aspects of Indian theatre.

Karanas in Natyashastra

Karana in Natyshastra is a technical term which in Sanskrit means "doing". According to Natyashastra Karanas is the framework for the "margi" productions that would spiritually enlighten the spectators. As per Natyashastra one who performs well would be free from all sins and would secure a place in the abode of this deity. It is a combination of the three elements: leg movements, gesture for hands and posture for the body. It is not a static concept.

Karanas have been interpreted well by Padma Subramanyam that were based on 108 movement phrases describing specific leg, hip, body, and arm movements that have been accompanied by hasta mudras.

The Angaharas are evolved through Karanas. While dancing the simultaneous movements of hands and feet can be called Karana. One matrika is made up of two Karanas. Out of three karanas a Kalapaka is evolved. A Mandaka is evolved out of four Kalapaka and a Sarfighataka is evolved out of five. Some of the well known Angaharas consists of six to nine Karanas.

Some of the one hundred and eight Karanas are Talapuspaputa, Vartita, Valitoru, Apaviddha, Samanakha, Lina, Svastikarecita Mandalasvastika, Nikuttaka, Ardhani-kuttaka, Katicchinna, Ardharecita,. Vaksassvastika, Unmatta, Svastika, Prsthasvastika, Diksvastika, Alata, Katisama, Aksiptarecita, Viksiptaksipta, Ardhasvastika, Ancita, Bhujanga Trasita, Urdhvajanu, Nikuncita, Matalli, Ardhamatalii, Recaka-nikuttita, Padapaviddhaka, Valita, Lalita, Danda Paksa, Nupura, yaisiikharecila, Bhrama-raka, Catura, Dandakarecila, Vrscikakuttita, Katibhranta, Latavrscika, Chinna, Vrscikarecita, Viscika, Vyamsita, Parsvanikuttana, Lalatatilaka, Kuncita, Cakramandala, Uromandala, Aksipta, Talavilfsila, Argala, Viksipta, Avrtta, Dolapada, Vivrtta, Vinivrua, Parvakranta, Nisumbhita, Vidyudbhranta, Atikranta, Vivartitaka, Gajak-ridita, Talasamsphotita, Garudaplutaka, Gandasuci, Parivrtta, Parsvajanu, Grdhravalinaka, Sannata, Suci, Ardhasuci, Suri-viddha, Apakranta, Mayoralalita, Sarpita, Dandapada, Harina-pluta, Prerikholita, Nitamba, Skhalita, Karihasta, Prasavpita, Siriihakridita, Simhakarsita, Udvrtta, Upasrta, Talasamghattita, Janita, Avahitthaka, Nivesa, Elakakradita Urudvrtta, Mada-skhalita, Visnukranta, Sambhranta, Viskambha, Lol`taka, Sakatasya, and Gangavatarana.

These Karanas are probably employed in dance, fight, personal combats. The foot movements are allotted to the exercise of Sthanas and Carls must be considered to the Karanas also.

There are still some elderly devadasis who perform all the 108 karanas. However in most contemporary Bharatnatyam or Odissi schools only 50-60 karanas have been taught.

Performing of the same karana vary depending on various Indian classical styles.

Rules of Drama in Natyashastra

Rules of drama in Natyashastra reveal the genres of drama, plot structure, doctrine of bhava and rasa. The three major types of genres of drama are major, minor and love drama. Plot structure, plot elements, rasa and bhava have been elaborated.

Genres:

Rupaka or Major drama - there are ten types and the most common is the Nataka which contains five to ten acts. Nataka is based on a historical event or myth. Hero is given the most importance. A specific passion would feature in the plot. Time period is short and it is prolonged by intervals of narration. In case of a ten act it is known as Maha nataka.

Upa-rupaka or minor drama - There are eighteen types.

Prakarana or Love drama - These are totally fictitious and as such do not use any other source than invention.

Plot Structure:

Action possesses a five part development:

* Arambha is the desire to attain something

* Prayatna is the organized effort to achieve the goal

* Prapti-sambhava is the "possibility of success" regards to the efforts spent and the obstacles that needs to be conquered.

* Niyatapti is assurance of success

* Phalagama is the attainment of success

There are five plot elements: germ, drop, episode, incident and the conclusion.

The five critical meeting points of the plot are Mukha or the opening, Pratimukha or progression, Garbha or development, Vimarsha or pause, Nirvahana, conclusion or catastrophe

Doctrine of Rasa

Rasa is "the essence of impersonal emotion". According to Bharata, the drama creates "a dispassionate delight in the audience who have been able to look at life gradually and see it as a result of skill of the dramatist in presenting the eight major sentiments. In order to balance eight major "stable sentiments" and thirty-three "unstable sentiments" in a harmonious way" the bhava needs to be produced.

The eight "stable," bhavas are:

Rati or sringara: desire, affection, erotic longing

lasa or lasya: laughter, comic or farcical joy, not involving cynicism or derision

krodha or rudra: anger arising from ill treatment

shoka or karuna: sadness resulting from separation from a loved one

utsasha or vira: pride in one`s own powers which lead to a display of energetic enterprise, bravery, charity or forgiveness

bhaya or bhayanaka: fear of reproach or attack

jugupsa or bibhatsa: aversion or loathing

vismaya or adbhuta: wonder, the connotation being that something evoking childlike surprise in encountered

The thirty-three "unstable" bhavas are: discouragement, weakness, apprehension, weariness, contentment, stupor, joy, depression, cruelty, anxiety, fright, envy, arrogance, indignation, recollection, death, intoxication, dreaming, sleeping, awakening, shame, demonic possession, distraction, assurance, indolence, agitation, deliberation, dissimulation, sickness, insanity, despair, impatience and inconstancy.

Musical Instruments in Natyashastra

Musical Instruments in Natyashastra are described as four different kinds. They are stringed, instrument of percussion, solid and hollow. The stringed instruments have strings. The instruments of percussion include drums. Cymbal belongs to the solid type and the hollow consists of flutes. As far as the dramatic performance is concerned these have three fold applications: that in which stringed instruments are mainly used, that in which percussion instruments are mainly used and the general application during the dramatic performance.

Musical Instruments in Natyashastra are described as four different kinds. They are stringed, instrument of percussion, solid and hollow. The stringed instruments have strings. The instruments of percussion include drums. Cymbal belongs to the solid type and the hollow consists of flutes. As far as the dramatic performance is concerned these have three fold applications: that in which stringed instruments are mainly used, that in which percussion instruments are mainly used and the general application during the dramatic performance.

In the orchestra or the stringed instruments the singer, the players of Veena and bansuri appear. Players of Mridanga, Panava and Dardara are called Avanaddha Varga or orchestra of covered instruments

The orchestra pertaining to actors and actresses of the Uttama, Adhama and Madhyama kinds occupy various places on the stage at the time of drama. Through various kinds of music Natya is embellished. In this manner Gana, Vadya and Natya that depend on diverse things should be made by the sponsors of the play like the Ajitacakra.

The playing on the stringed instruments that is accompanied by various other instruments is known as Gandharva. It includes Svara, Tala and Pada. The source is vocal music, the Veena and the flute. There are three kinds of Gandharva: Svara, Tala and Pada.

Svaras: Svaras have two bases: the human body and the Vina. The Svaras that arise from the two are: Gramas Murcchanas, Tanas, Sthanas (Voice Registers), Vrittis Sadharana Svaras, Varnas Alamkaras, Dhatus, Srutis and Jatis.

Vocal Music have the following: Svaras, Gramas, Alankaras, Varnas, Sthanas, Jatis and overlapping notes are available in the Veena of the human throat (vocal music).

There are twenty formal aspects of Tala: Avapa, Niskrama, Viksepa Pravesaka, Samya, Tala, Sannipata, Parivarta, Vastu, Matra, Vidari Anga, Lava, Yati, Prakarana, Giti, Avayava Marga, Padabhaga and Pani. The Seven Svaras are Sadja (sa), Rsabha

(Ri), Gandhara (Ga), Madhyama (Ma) Paficama (Pa), Dhaivata (Dha) and Nisada (Ni). As far as their relation to an interval of Srutis are concerned there are of four kinds like Vadi (Sonant), Samvadi (consonant), Anuvadi (Assonant) and Vivadi (Bisonant).

That which is an important part anywhere it is known as Vadi. Those two Svaras which are at an interval of nine or thirteen Srutis from each other are Samvadins. They are Sadja and Madhyama, Risabha and Dhaivata, Gandhara and Nisada in the Sadja Grama.

Carl movements in Natyashastra

Carl movements in Natyshastra refer to the foot movements. A dance is pervaded by movements of Carl. All movements proceed from the Carl. Discharge of missiles is attended with Carl movements. When fighting scenes are depicted in the stage Carl movements are used. Everything concerned and projected as Natya is a part of the Carl movement. No part of Natya can be performed without a Carl.

There are two types of carl movement: Bhaumi Carl and Akdsi Ki Carl. There are sixteen Bhaumi or Earthly Carls and they are: Samapada, Sthitavartai, Sakatasya, Adhyar-dhika, Casaeati, Vicyava, Edakakrdita, Baddha, Uridvrtta, Acidita, Ulsyardita, Janita, Syandita, Apaspandila, Samotsarifa Mattalli and Mattalli.

There are sixteen carls and they are Atikranta, Apakranta, Parsvakranta, Urdhvaianu, Kuficita, Nupurapadika, Dolapada, Aksipta, Aviddha, Udvrtta, Vidyudbhranta, Alata, Bhujariga Trasita, Mrgaputa, Danda and Bhramar.

Samapada - Both the feet are kept close together and the nails are symmetrical. The actor stands on the spot.

Sthitavartai - One foot is drawn up in order to cross the other foot. Thereafter this movement is repeated with the other foot after keeping the feet apart.

Sakatasya - Actor`s body is kept erect. One foot is in Aprataiasancara state and he keeps the chest in Udvahita state.

Adhyar-dhika - The left foot is kept at the back of the right one and then the right foot is removed

Casaeati - In the Carl called Casagati the right foot is put forward and then drawn back. At the same time the left foot is drawn back and put forwards.

Vicyava - The feet are separated from the state of Samapada.

Edakakrdita - the actor jumps up and falls down alternatively.

Baddha - The two shanks are crossed in the form of Svastika. Then the thighs are kept sideways.

Uridvrtta - The heel of a Talasapta foot is to be placed facing outwards; of the shanks one is to be slightly bent and the thigh is turned up.

Addita - Where an Agratala Sancara foot rubs against either the forepart or the back of another foot.

Ulsyardita (or Utspandita) - If the feet move gradually in and out (i e. sideways) in the manner of Recaka, the Carl is called Utsyandita.

Janita - A band is held on the chest and the other hand is moved round. The feet are to be kept in Talasancara manner.

This Carl is called Janita. Syandita one of the feet is put forward five Talas away from the other. This Carl is called Syandita.

Apasyandita - If the other foot is put forward five away from the previous one it is Apasyandita.

Samotsarita-Mattalli - Both the Talasancara feet have a circular movement while going back.

Matalli - A backward step with a circular movement and the hands are Udvestita and then Apaviddha.

The Carl movements:

Atikranta - A foot is raised and stretched forward. After lifting up it is allowed to fall upon.

Apakranta - Valana twisting and turning is performed by both the thighs and then a Kuncita foot is raised and immediately set down sideways.

Parsvakranta - A foot is raised in the Kuncita state and stretched beyond the knee. Another is thrown up and brought near the side.

Urdhvaianu - A Kuncita foot is lifted up and the knee is brought up to the level of the Chest and the other knee is kept free from movement.

Nupurapadika - A foot is lifted up and taken behind another foot and it is quickly caused to fall on the ground.

Dolapada - Lift up the Kuncita foot and rock it from side to side. Then allow it to fall on the ground as an Ancita foot.

Aksipta - A Kuncita foot is thrown up and immediately it is placed on a foot while the shank of the remaining leg is crossed.

Aviddha - A Kuncita foot in the Svastika state is stretched out and it is allowed to fall on the ground quickly as an Ancita foot.

Udvrtta - In the Aviddha Carl the Kuncita foot is taken round the thigh of the other leg, thrown up and then caused to fall on the ground.

Vidyudbhranta - One foot is circled backwards and stretched so as to touch its top: then the head is moved in a circle.

Alata - One foot is stretched backwards and then thrust in after being twisted. Thereafter it falls on its heel.

Bhujariga trasita - After throwing up a Kuncita foot there shall be a three cornered twisting round of the thigh hip and the knee.

Dravidian Contribution to Natyashastra

Dravidian Contribution to Natyashastra dates back to a long time. There are lots of aspects that have been contributed to various aspects of Natyashastra through the Dravadian culture. Natyashastra of Bharata is considered the fifth Veda, thereby clearly suggesting that it was not in the original Aryan fold. Bharata and his hundred sons (evidently a clan) who staged the first drama on the occasion of Indra Dhvajotsava did not enjoy the same Vedic status as the pure Aryans. These hints also strengthen the inference that the Dravidians might have given their theatrical traditions to the Aryans. Natyasastra itself is said to bear an eloquent testimony to its incorporating Dravidian dramatic methods.

Dravidian Contribution to Natyashastra dates back to a long time. There are lots of aspects that have been contributed to various aspects of Natyashastra through the Dravadian culture. Natyashastra of Bharata is considered the fifth Veda, thereby clearly suggesting that it was not in the original Aryan fold. Bharata and his hundred sons (evidently a clan) who staged the first drama on the occasion of Indra Dhvajotsava did not enjoy the same Vedic status as the pure Aryans. These hints also strengthen the inference that the Dravidians might have given their theatrical traditions to the Aryans. Natyasastra itself is said to bear an eloquent testimony to its incorporating Dravidian dramatic methods.

The technique of the Kannada theatre - Bayalata, the Tamil theatre - Terukkuttu, and the Telugu thetre - Veethi nataka, very closely resemble the modes and technique elaborated by Natyashastra.

Looking at the variety and originality of the Dravidian metres, music and dance, one would feel that they had a richer wealth of the art of dance and drama than the Aryans. In the Aryan and non-Aryan process of mutual exchange, many a non-Aryan God and Rishi found a place in the Aryan hierarchy and so, it is not improbable that the Aryans borrowed the great theatrical traditions of the Dravidians. Once taken, they made it their own by moulding it into a new shape. In other words, the so called marga should have been evolved out of the contact with the desya. Among the significant contributions possibly made by the ancient Dravidian theatre to Sanskrit theatre or Dramaturgy are perhaps modes of dancing and music, devotional themes and important characters like Sutradhara and Vidhusaka. South India, and particularly Karnataka is the home of the Bhakti movement and the soil always had the seed of this movement centuries before the Dasas came up to preach. It is not improbable that the Aryans inculcated the Bhakti marga and based their plays on themes of bhakti after their close contact with the Dravidians. The folk theatre of Karnataka has still preserved some relics of such ancient performances of the Dasas.