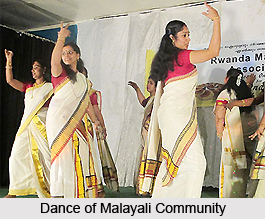

Malayali People are formed by the coming together of four groups. With the Nambudiri Brahmins, the pattern by which the principal people of Kerala came together is complete; the mountain tribes and the fishermen and serf classes of the lowlands emerge as the original inhabitants, descendants of megalithic immigrants; the Nayars represent the true Dravidian element, pressed southward during the earlier parts of the first millennium B.C. by the spread of Aryan domination north of the Vindhya mountains; the Ezhavas appear as a seaborne people, probably from Ceylon, arriving with the richest gift Kerala has ever received, the coconut palm, at some time shortly before the beginning of the Christian era and not long after the time when the Nambudiri Brahmins wandered down from a Buddhist north where their Vedic conservatism was temporarily unwelcome. When these four main groups had come together, the Malayali people were established.

Malayali People are formed by the coming together of four groups. With the Nambudiri Brahmins, the pattern by which the principal people of Kerala came together is complete; the mountain tribes and the fishermen and serf classes of the lowlands emerge as the original inhabitants, descendants of megalithic immigrants; the Nayars represent the true Dravidian element, pressed southward during the earlier parts of the first millennium B.C. by the spread of Aryan domination north of the Vindhya mountains; the Ezhavas appear as a seaborne people, probably from Ceylon, arriving with the richest gift Kerala has ever received, the coconut palm, at some time shortly before the beginning of the Christian era and not long after the time when the Nambudiri Brahmins wandered down from a Buddhist north where their Vedic conservatism was temporarily unwelcome. When these four main groups had come together, the Malayali people were established.

The language spoken by the Malayali people is known as Malayalam; and Malayalam is also one of the ancient names of the state of Kerala, a descriptive name meaning the land of sea and hills. Whether this language is a derivation of Tamil or springs directly from a common Dravidian stock is still being debated by linguists. Tamil was certainly the language of literature and of inscriptions in Kerala until the middle ages, but it may never have been more than a language of the court and of poets and scholars - unspoken by the people, as both Persian and Sanskrit language were for long periods in North India. One fact, however, is certain: Malayalam has a greater Sanskrit content than any of the other Dravidian tongues, Tamil, Telugu or Canarese; this is due to the fact that the influence of the Nambudiris, treasurers of Sanskrit culture, was becoming dominant at precisely the time - the eleventh century onwards - when Malayalam first began to be used as a written language.

Malayalam is a Dravidian tongue but it differs considerably even from the related Tamil of Chennai and it has no relationship at all to the Hindi. The difference in language is important, not only because it isolates the Keralite, who can normally communicate with another Indian only by using a foreign language, English, but also because it provides the basis on which Kerala came into existence as a modern state.

Onam is the principal festival of the Malayalis. Onam is the year`s great fertility rite, the ceremony of gratitude for the never-failing fruits of a tropical climate, but it is also a festival that re-enacts one of the most important legends of the Malayali people. On the eve of Thiru Onam, the second day of the festival, ziggurat-like structures of flowers are placed in the entrances to Keralite houses; these are intended to welcome, on his annual return the following morning from the underworld, the legendary king Mahabali, who ruled over Kerala in the golden age before caste existed, when all men were equal no man was poor, and there was neither theft nor dread of thieves.

But there is another aspect to the Onam festival than either forgotten history it revives or the universal symbols of fertility with which it links Mahabali and his legend. To educated Malayalis - and that means a majority in a state which has long cherished the highest literacy rate in all India - Mahabali is no more that a figure of past or present reality than Santa Claus is to us. Yet they still celebrate his festival as richly as they can afford, partly because of the sentiments of brotherhood and good fellowship which the idea of Onam, like the idea of Christmas, generates, but also with an almost magical feeling that in some way what they do on the day when Mahabali returns may bring a gleam of his golden age into a time in which, for most Keralites, life shows its feet of clay.

But there is another aspect to the Onam festival than either forgotten history it revives or the universal symbols of fertility with which it links Mahabali and his legend. To educated Malayalis - and that means a majority in a state which has long cherished the highest literacy rate in all India - Mahabali is no more that a figure of past or present reality than Santa Claus is to us. Yet they still celebrate his festival as richly as they can afford, partly because of the sentiments of brotherhood and good fellowship which the idea of Onam, like the idea of Christmas, generates, but also with an almost magical feeling that in some way what they do on the day when Mahabali returns may bring a gleam of his golden age into a time in which, for most Keralites, life shows its feet of clay.

In the early period the Malayalis themselves took an active part in the foreign trade, and many of the merchants whom the Alexandrian shipmasters encountered in Arabian ports during Ptolemaic times were Indian. A negative result of the traditional emphasis of Kerala on crops for foreign trade is the fact that for centuries it has suffered from shortage of rice, which is the favourite food of the Malayali people. Food crises are nothing new on the Malabar Coast. As long ago as the sixteenth century the Zamorin of Kalikod (Calicut) was importing rice to feed his people, and on one occasion when the Portuguese destroyed a flotilla of his grain ships a minor famine was only narrowly averted. Then, as now, the Malayali farmers were already concentrating on growing spices for the foreign market rather than food for themselves.

One quality which the Malayalis lack completely is reticence, so that the sources of oral information were always copious and easily tapped. On the other hand, it is no exaggeration to say that there are as many shades of opinion as there are literate inhabitants. Yet this, as one soon discovers, is only one side of the Malayali character. Despite their intellectual individualism and their predilection for political change, the people of Kerala are highly group-conscious and, in their own way, traditionalist.

Even more unusual in patriarchal India, until a generation ago the majority of Malayan Hindus lived according to a matrilineal joint family system which embodied the practice of polyandry. Even now that system has not completely broken down, and it legally governs the inheritance of ancestral as distinct from personal property: a daughter and all her children inherit equal shares in such property, but the son only inherits his own share and his children must inherit through their mother`s family. But probably the most important effect of the matrilineal system is that it has left Malayali women with an influence and an independence of outlook which one will not find anywhere else in India south of the Tibetan - influenced regions on the Himalayan frontiers: in particular, by maintaining a position for the woman within her own family, it has prevented widowhood from becoming the sordid tragedy which it was -and to a great extent still is - in other Hindu societies.

The appearance of the countryside is shaped by the taste of the Malayalis. Every Malayali likes to live apart, even if, as most villagers do, he lives on someone else`s land and cannot even pick the coconuts from the trees that give him shade. His tiny hut may be overcrowded. Since they cling to this kind of village existence, many country people in Kerala become habitual commuters. Even the benevolent paternalism of modern industry has been defeated by the obstinate ruralism of the Malayali. Poor Keralans live simply from necessity, but their wealthier compatriots make simplicity a cult, so that among Malayalis one rarely sees the ostentation which in northern India is almost regarded as a duty of the rich. The local mores set a value on eating frugally and doing without elaborate furniture; one may wear fine rather than coarse cotton, but one does not wear silk.

A majority of Malayalis are still villagers, and even those who live in the towns like to feel that they have kept an acre or two among their native coconut groves to which they can some day return. The love of the country goes with an almost mystical faith in its destiny. Educated Malayalis are too intelligent and too knowledgeable to ignore the problems of Kerala: in fact they enjoy nothing more than talking about them. Yet even the most extreme of conversational cynics never wrote off the future of Kerala as hopeless.

The simplicity of Keralite life tends to mask its poverty, for it goes with a sense of order. A Malayai house may be no more than a hut of sticks and dried leaves, raised on a clay stoop in the midst of a first-floored compound. This traditional orderliness, which punctuates the Malayali`s daily life with rituals of cleanliness, finds its parallel in the patterns that shape the Kerala landscape. Many Malayali intellectuals and officials return to their native villages in middle age and take an active part in local activities, so that there is even a cultural sophistication about rural life in Kerala; in many respects it is almost urban.