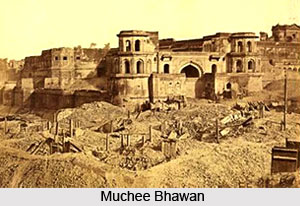

The city of Lucknow (now known as Lucknow) built on the west bank of the Gomti river, but having suburbs on the east bank, lies forty-two miles to the east of Kanhpur (Kanpur), and 610 miles from Calcutta. All the principal buildings lie between the city and the riverbank. Here also are the Residency and its dependencies, covering a space 2,150 feet long from northwest to south-east, and 1,200 feet broad from east to west. A thousand yards to the west of it was the Machchi Bhawan, a turreted building used for the storage of supplies. Close to it, and in the present day incorporated with it, is the Imambarah, a mosque, 303 feet by 160 feet. A canal, which intersects the town, falls into the Gomti about three miles to the south-east of the Residency, close to the Martiniere. That about three-quarters of a mile to the south-east of this is the Dilkusha, a villa in the midst of an extensive deer park.

The city of Lucknow (now known as Lucknow) built on the west bank of the Gomti river, but having suburbs on the east bank, lies forty-two miles to the east of Kanhpur (Kanpur), and 610 miles from Calcutta. All the principal buildings lie between the city and the riverbank. Here also are the Residency and its dependencies, covering a space 2,150 feet long from northwest to south-east, and 1,200 feet broad from east to west. A thousand yards to the west of it was the Machchi Bhawan, a turreted building used for the storage of supplies. Close to it, and in the present day incorporated with it, is the Imambarah, a mosque, 303 feet by 160 feet. A canal, which intersects the town, falls into the Gomti about three miles to the south-east of the Residency, close to the Martiniere. That about three-quarters of a mile to the south-east of this is the Dilkusha, a villa in the midst of an extensive deer park.

To the north-east of the Residency lay the cantonment, on the left bank of the Gomti, communicating with the right bank by means of two bridges - one of stone, near to the Machchi Bhawan, the other of iron, 200 yards from the Residency. Re-crossing by this to the right bank there comes the palaces, between the Residency and the Martiniere. To .the south-west of the town, approximately four miles from the Residency, is a walled enclosure of 500 square yards called the Alambagh, commanding the road to Kanhpur. In May 1857, the troops at Lucknow consisted of the greater part of the 32nd foot, about 570 strong, fifty-six European artillerymen, a battery of native artillery, the 13th, 48th, and 71st Regiments N. I., and the 7th Native Light Cavalry. Up to the time of the receipt by Sir Henry Lawrence of the patent of Brigadier-General, these troops had been employed in the way then common in India. The sipahis had been entrusted with the care of important buildings, the Europeans being sheltered as much as possible from the heat of the sun.

Sir Henry at once changed this order. He reduced the number of posts to be guarded from eight to four, three of which he greatly strengthened. All the magazine stores he removed into the Machchi Bhawan, to be guarded by a company of the 32nd and thirty guns. At the treasury, within the Residency compound, he stationed 130 Europeans, 200 natives, and six guns. At the third post, between the Residency and the Machchi Bhawan, commanding the two bridges, he located 400 men, Europeans and natives, with twenty guns, some of them eighteen-pounders. The fourth post was the travellers` bungalow, between the Residency and the cantonment. Here he posted two squadrons of the 2nd Oudh Native Cavalry, with six guns.

In the cantonment, on the left bank of the Gomti, there still remained 340 men of the 32nd foot, fifty English gunners, six guns, and a complete battery of native artillery. The 32nd were, towards the end of May, reduced by eighty-four men, despatched to the aid of Wheeler at Kanhpur. The 7th Native Cavalry remained at Mudkipur, seven miles distant from the Lucknow cantonment.

On the 27th Sir Henry wrote to Lord Canning that the Residency and the Machchi Bhawan `were safe against all probable comers.` That very day, however, he had confirmation that the countryside districts were billowing around him, and he had to despatch one of the ablest of his assistants, Gould Weston, to Maliabad, fifteen miles from Lucknow, to restore order. Further, also on the 27th, he despatched Captain Hutchinson, with 200 sowars and 200 sipahis, to the northern frontier of the province. The measure certainly rid Lucknow of the presence of 400 disaffected soldiers. But it resulted in the murder by them of all their officers save one. Hutchinson was able to return safely to his post.

Before this mutiny occurred (7th and 8th June) the catastrophe at Lucknow had come upon Sir Henry. On the night of the 30th of May the greater number of the sipahis (soldiers) of the 71st N. I. rose in revolt, fired the bungalows, murdered Brigadier Handscomb and Lieutenant Grant, wounded Lieutenant Hardinge, and attempted further mischief. The attitude of the European troops completely baffled them, and they retired in the night to Mudkipur, murdering Lieutenant Raleigh on their way. There, at daylight, Sir Henry followed them. Though deserted by the troopers of the 7th N. L. C, who joined the mutinied 71st N. I., and by some men of the 48th N. I., drove them from their position, and pursued them for some miles. Their action had, in fact, proved advantageous to Sir Henry Lawrence. It had rid him of feigned friends, and had shown him upon whom he could bank. The great bulk of the 13th N. I. had proved loyal. But the whole of the 7th Cavalry, more than two-thirds of the 71st N. I., a very large proportion of the 48th N. I., and a few of the 13th N. I. had shown their hands. Their departure enabled Sir Henry still further to concentrate his resources.

Every day intelligence brought news of the seriousness of the crisis from the faraway districts. At Sitapur, fifty-one miles from Lucknow, there had been incendiarisms at the end of May. On the 2nd of June the sipahis of the 10th Oudh Irregulars, stationed there, had thrown the flour sent from the town for their consumption into the river, on the excuse that it had been adulterated with the view of destroying their caste. On the 3rd the 4lst N. I. and the 9th Irregular Cavalry broke out in mutiny, and murdered many of their officers and residents, under circumstances of abnormal barbarousness. The number of men, women, and children so murdered amounted to twenty-four.

At Malaun, forty-four miles to the north of Sitapur, the natives rose as soon as they heard of the events at the latter place. At Muhamdi, on the Rohilkhand frontier, the work of carnage on disarmed men, women, and children, on the 4th of June, did not exceed in atrocity by any similar event during the outbreak. At Faizabad, at Sikrora, at Gondah, at Bahraich, at Malapur, at Sultanpur, at Saloni, at Daryabad, at Purwa, in fact at all the centres of administration in the province there were, during the first and second weeks of June, mutinies of the sipahis, risings of the people, and conduct generally on the part of the large landowners. These actions proved that their sympathy was with the revolters. By the 12th of June Sir Henry Lawrence had realised that the only spot in Oudh in which British authority was still respected was the Residency of Lucknow.

Sir Henry was by this time chasing, on the morning of the 31st of May, the mutinied sipahis from the station of Mudkipur. Between that time and the 11th June his health, weakened by long service in India, had given way. But the measures of Officer Gubbins (the officer who acted for him during his illness), which were in direct opposition to the principles which he had instilled, had the effect of rousing him from his bed of sickness. One of his strong points was to maintain at Lucknow as many sipahis as would serve loyally and faithfully. Without the aid of sipahis the Residency, he felt, could not be defended against the masses which a province in insurrection could bring against it. Officer Gubbins, during his illness, had despatched to their homes all the sipahis belonging to the province of Oudh. Sir Henry promptly called them back. Believing he might successfully appeal to that class which had in former years enjoyed the benefits of British service, and later had not been subjected to the tactics of the crusaders, he despatched circulars to all the pensioned sipahis in the province inviting them to come to Lucknow.

The purpose was to defend the masters to whom they owed their pensions, and whose interests were bound up with theirs. The response to these circulars was remarkable. More than 500 grey-headed soldiers came to Lucknow. Sir Henry gave them a cordial welcome, and selecting around 170 of them for active employment, placed them under a separate command. With these and the loyal sipahis he had now nearly 800 able-bodied men fit for any work they might be called upon to perform.

However, umpteen disloyal sipahis still remained in his vicinity. Of these, the cavalry and infantry of the native police broke out on the night of the 11th and the morning of the 12th. Vainly did their commandant, Gould Weston endeavour to recall them to their duty. He owed his own life to his remarkable daring. The 32nd, sent in pursuit, followed up the mutinied policemen and inflicted some damage. But the ground was broken, the heat was great, and the mutineers had a considerable start. It was in many respects an advantage to be rid of them.

In view of the great crisis now so near, Sir Henry had continued to strengthen the slight defences of the Residency enclosure, and to make the Machchi Bhawan as rock-solid as possible. He had originally resolved to hold both places. But as soon as he had realised the fact that the small number of his troops would permit only of his retaining one portion against the surging masses of the city and the provinces, he had decided to concentrate all his forces within the Residency. He still, however, for the moment held the Machchi Bhawan, believing that the report of his preparations there would have some effect on the rebels.

Sir Henry was not quite certain, at this time that he would be beleaguered at all. Everything depended on Kanhpur (Kanpur). If British reinforcements could reach that place whilst Wheeler should still be holding it, then, he argued, the people of Oudh, in face of an English force within forty-two miles, would not dare to attempt the siege. He feared very much, however, for Kanhpur. He would have marched to assist the place if it had been possible, but, in the face of the masses of the enemy holding the Ganges, he could not have reached Wheeler`s entrenchment. Sir Henry would have certainly been destroyed himself. At length, on the 28th, he heard that Kanhpur had fallen, and that the rebels of his own province, cheered by the news, had advanced in force to the village of Chinhat, on the Faizabad road, eight miles from the Residency.

Sir Henry was not quite certain, at this time that he would be beleaguered at all. Everything depended on Kanhpur (Kanpur). If British reinforcements could reach that place whilst Wheeler should still be holding it, then, he argued, the people of Oudh, in face of an English force within forty-two miles, would not dare to attempt the siege. He feared very much, however, for Kanhpur. He would have marched to assist the place if it had been possible, but, in the face of the masses of the enemy holding the Ganges, he could not have reached Wheeler`s entrenchment. Sir Henry would have certainly been destroyed himself. At length, on the 28th, he heard that Kanhpur had fallen, and that the rebels of his own province, cheered by the news, had advanced in force to the village of Chinhat, on the Faizabad road, eight miles from the Residency.

Sir Henry promptly decided to move out and attack the rebels. He held that nothing would tend so much to maintain the prestige of the British at this critical juncture as the dealing of a heavy blow at their advanced forces. Accordingly, he moved his troops from the cantonment to the Residency, and at half-past six o`clock, on the morning of the 30th of June, set out in the direction of Chinhat, with a strengthened force. The force was composed of 300 men of the 32nd foot, 230 loyal sipahis, a troop of volunteer cavalry, thirty-six in number, 120 native troopers, ten guns, and an eight-inch howitzer. Of the ten guns, four were manned by Englishmen and six by natives. The howitzer was on a limber drawn by an elephant driven by a native.

After marching three miles along the metalled road, the force reached the bridge spanning the rivulet Kukrail. Here Sir Henry halted his men, while he rode to the front to scout his goal. Reining in his horse on the summit of a rising ground, he gazed long and anxiously in the direction of Chinhat. Not a movement was to be seen. Nor when he turned his glass in other directions did he meet with better fortune. There was no enemy. He sent back, then, his assistant Adjutant-General to order the column to retrace its steps. The column had begun to act on the order when suddenly there was spotted in the distance a mass of men moving forward. Instantly repealing his first order, Sir Henry sent fresh instructions that the column should advance. It advanced accordingly, and after proceeding a mile and a half, saw the rebels drawn up at a distance of about 1,200 yards. Their right side was covered by a small hamlet, their left by a village and tank, whilst their centre rested, uncovered, on the road. Just as the English sighted them the rebels opened fire.

Sir Henry at once deployed his men, and commanding them to lie down, returned the fire. The bombardment lasted more than an hour, when suddenly it ceased on both sides. Shortly after the rebels were spotted in two masses, advancing against both flanks of the English. The ground lent itself to such a movement, made by vastly superior numbers. For, parallel to the line formed by the men of the 32nd, was the village of Ishmailganj, and the rebels were now pouring into it. The seizure of this village by one-half of the rebel force was a very masterly manoeuvre, for it enabled the rebels to pour a concentrated flanking fire on the English line. Meanwhile, the other wing was threatened from the opposite side. Blazing success attended the movement.

In an incredibly short span of time the 32nd had lost nearly half its numbers, and it became clear that the English force would be destroyed unless it could reach the bridge over the Kukrail before the enemy could get there. The retreat was at once ordered, and the British force, though pounded with grapeshots and harassed by cavalry all the way, pushed on vigorously. Just, however, as the retreating troops approached the bridge, they noticed that bodies of the enemy`s cavalry had worked round and were heading them in that direction. The commander of the thirty-six volunteers observing the movement, and realising on the instant its importance, dashed, at the head of his men, against the rebel cavalry. The latter did not wait to receive the sudden onslaught, but giving way at the sight of the English, sought safety in flight.

Still the rebel infantry pressed on, and what was worse, the gun ammunition of the British was exhausted. In this crisis Sir Henry pushed his men across the bridge; then placed the guns on it, and ordered the gunners to stand beside them with the port-fires lighted. The subterfuge produced the desired effect. The rebels shrunk back from attacking a narrow bridge defended, as they supposed, by loaded guns. The British force then succeeded in gaining the shelter of the city, and in retiring in some sort of order on the Machchi Bhawan and the Residency. But their losses had been severe, and they had left behind them the howitzer and two field-pieces.

Sir Henry Lawrence, crossing the Kukrail bridge, and disposing his guns, had galloped off, leaving Colonel Inglis to bring the force to the Residency. It was unattended by anyone save his assistant Adjutant-General, Captain Wilson. After arriving there, he despatched fifty of the 32nd, under Lieutenant Edmonstone, to defend the iron bridge against the rebels. This, despite the efforts of the overjoyed enemy, they succeeded in doing, though with some loss. The rebels, however, had penetrated within the city, and, aided by the mass of the population, began to loophole many of the houses in the vicinity of the Residency and the Machchi Bhawan. They went so far as to attack one of the posts of the Residency, afterwards known, from the officer who ultimately commanded there, as Anderson`s post.

The following evening Sir Henry, threatened at both points by the enemy, caused the defences of the Machchi Bhawan to be blown up, and concentrated his forces within the Residency enclosure. From that date, the 1st of July, began that legendary `leaguer`.