The post-classical period in India is usually looked at from the perspective of the political aftermath of the Muslim invasions and not as a situation which developed out of a continuous historical process. The accent is thus on the political fragmentation of the country and incessant war fares and not on a comprehension of the total social structure which such a political situation represented.

The post-classical period in India is usually looked at from the perspective of the political aftermath of the Muslim invasions and not as a situation which developed out of a continuous historical process. The accent is thus on the political fragmentation of the country and incessant war fares and not on a comprehension of the total social structure which such a political situation represented.

In the medieval period, the social structure encompasses local lords with pre-eminent social and political status in the area. The key figures of early medieval India were thus various groups of samantas, mahasamantas, mandalesvaras, mahamandalesvaras, rajakulas, rajaputras. These all are basically landed magnates but known by various regional expressions. The relationship between them and the heads of numerous royal families was perhaps variously defined and the system of court hierarchy in a kingdom was determined by the nature of this relationship. Such a situation fostered military adventurism which is reflected in the continuous formation of ruling dynasties. This process is tacitly admitted in contemporary political theory in which the concept of king received a flexible definition.

Some of the early medieval kingdoms were located in the perennial centres of power; others arose in relatively isolated zones and marked the beginning of new social processes in those areas. As in the earlier periods, these dynasties and kingdoms too desired legitimization within a Brahmanical framework. The political elites were thus dependent on the priestly class and such existing institutions as temples for securing effective grip over the areas they ruled. The brahmadeyas or predominantly Brahman villages were distributed throughout their territorial units, and deliberations of systematically constituted assemblies in such villages, consisting only of Brahman members, show that religious pursuits were not their only concern. The other category of grants, the devadanas, made the temple a focal point of activities not only in rural areas but, in some cases, in urban areas as well.

The point has often been made that the post-classical period represents a major structural change in Indian society. The economy was ruralized, and the vast number of assignments, resulting in the development of landed intermediaries, introduced feudal characteristics in it. Trade declined, urban centres fell into decay, and the old manufacturing guilds came to be reduced to the insignificant position of low sub-castes. The impressions that the sources give are those of a predominantly rural society organized in such a way as to yield the maximum quantum of revenue to the state. Trading activities had a comparatively subservient role in this political structure.

Moreover, the emergence of regions was not merely a political process; it had several cultural facets as well. The formation of castes was the result of acculturation and occupational changes, and an analysis of this process alone can provide an index of the cultural dynamics of the area. The same dynamics may be located in the chronological stages of the growth of regional languages. Sanskrit continued the official language, but what was typical of a region found the language of the area to be its best vehicle. This urge went to the extent of even regionalizing the epics.

The process of the emergence of various types of landed interests continued through different stages of early Indian medieval history. However, in the early medieval period the structure of such interests became so complex that a proper definition of property became almost impractical.

In fact the entire economic structure of the period rested on the recognition extended to various categories of people as appropriators of surplus from land. The Brahmans continued to receive patronage in the form of land grants; the religious establishments too emerged as a major beneficiary in this period. However, the concept of the King`s ownership did not conflict with various titles, held temporarily or permanently. Land came to be assigned to `vassals for military service, to members of the clan or family, and even to officers`. Sub-infeudation of titles in such a situation was common, and religious grants, being a symbol of social status, were made even by holders of relatively inferior rights.

In fact the entire economic structure of the period rested on the recognition extended to various categories of people as appropriators of surplus from land. The Brahmans continued to receive patronage in the form of land grants; the religious establishments too emerged as a major beneficiary in this period. However, the concept of the King`s ownership did not conflict with various titles, held temporarily or permanently. Land came to be assigned to `vassals for military service, to members of the clan or family, and even to officers`. Sub-infeudation of titles in such a situation was common, and religious grants, being a symbol of social status, were made even by holders of relatively inferior rights.

Theoretically, as in earlier periods, miscegenation was at the root of all mixed castes, and in the medieval period too thousands of mixed castes were produced through union between Vaisya women and men of lower castes. It was, however, a `hypothetical explanation of the increasing caste groups in the society` and the real reason for the proliferation of castes lay in the continuous process of acculturation, which brought new areas and new social groups within caste society. Even such groups as specifically mentioned to have been non-indigenous, the Khasas and the Hunas being two contemporary examples that came to claim high caste status.

New entrants into caste society had, however, varied status and even the same tribe could break up into several varnas and castes during the early medieval period. The Abhiras, for example, came to be grouped into Brahman, Kshatriya, Vaisyas, Mahasudras and so on. Some group of people were ranked as impure Sudras. Even the period witnesses `a phenomenal growth in the number of impure Sudras or untouchables`. In the higher echelons too new castes emerged. New professions such as that of a scribe rendering his service to various categories of court gave rise to the Kayasthas. In north India, among the chieftains arose a new category, that of the Rajaputras or Rajputs. By about the twelfth-thirteenth century AD., the number of Rajput clans in western India had been standardized as thirty-six but the structure was flexible and provided sufficient scope for mobility among ruling elites, as can be seen in the inclusion of the tribal Medas among the Rajaputras. Moreover, among the Brahmans too arose differentiation based on regions. Numerous early medieval epigraphs indicate special social prestige attaching to such regional castes as Kanauj Brahmans, Gauda Brahmans, Kolaiica Brahmans and so on. Some of the extracts provided here highlight `grama` as the basic territorial unit of social organization.

As per the norms of the society, one should carefully practice dharma (lawful duty) by work, mind and word, but one should not perform an act which, though legal, is unfavourable for the attainment of heaven and is disliked by the people. In the society of the medieval period, the Brahmans (priests) were in the forefront. Others are the Kshatriyas (warriors) and Vaisyas (producers and merchants), who are also as high in position as the Brahmans, being qualified to perform rituals as laid down in the Vedas. The Sudras (menials) who are not qualified (to act) according to the Vedas and have therefore got to be dependent on the three others for their living. But because the living of the Sudras is linked with the three other castes, they have been included in the caste system and are made the fourth caste.

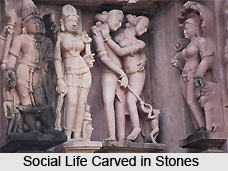

The people of the medieval society were religious and temple which emerged as a crucial religious institution in the earlier period was at this time closely associated with all major religious developments. Simultaneously with the growth of theistic sects grew the temples. Construction of temples was connected with contemporary consciousness about social position; many of the deities enshrined in south India bore the personal names of the devotees.

The single major factor which tremendously influenced the contents of religions in the early medieval period was Tantricism.

The transformation of Jaina yaksinis into independent cults of worship associated with Tantric practices is perhaps the best illustration of the range of Tantric influence on the religious of early medieval India. In philosophy the debates of the earlier period passed on to a new phase with the subjugation of heterodoxy by Vedantic thought. The phase coincided with the decline of Buddhism. Vedanta, through Sankara, its greatest exponent, brought even the other deviant Brahmanical of thinking to task.

The transformation of Jaina yaksinis into independent cults of worship associated with Tantric practices is perhaps the best illustration of the range of Tantric influence on the religious of early medieval India. In philosophy the debates of the earlier period passed on to a new phase with the subjugation of heterodoxy by Vedantic thought. The phase coincided with the decline of Buddhism. Vedanta, through Sankara, its greatest exponent, brought even the other deviant Brahmanical of thinking to task.

The society in medieval India was structured with caste system and distinct reigning system. The people had religious mind and during this time several religious beliefs and cults were developed. Construction of temples were started to worship different deities and religions. The social structure that was framed during the early medieval period is still existent but the severity of the social distinctions is lessoned with the time.