Introduction

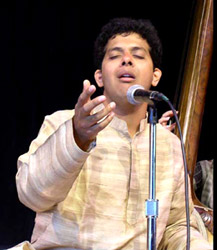

Khayal is the outcome of the incorporation of two cultures. It is the fruit of the democratization that North Indian classical music underwent from the 18th century on - a development that was to have far-reaching effects in terms of its wide appeal and it`s even wider reach. The form, as one hears today is most definitely the result of a cumulative process of experimentation and liberalization that took place from the 18th century on, and continues well into the present. The very presence of the `unalloyed` music of South India, which was largely free from Islamic conquests, points to the cultural divergence that took place between North and South India, which was followed by Islamic invasions. Khayal is possibly one of the finest creations to emerge from the melting pots of Hindu and Muslim imaginations.

Khayal is the outcome of the incorporation of two cultures. It is the fruit of the democratization that North Indian classical music underwent from the 18th century on - a development that was to have far-reaching effects in terms of its wide appeal and it`s even wider reach. The form, as one hears today is most definitely the result of a cumulative process of experimentation and liberalization that took place from the 18th century on, and continues well into the present. The very presence of the `unalloyed` music of South India, which was largely free from Islamic conquests, points to the cultural divergence that took place between North and South India, which was followed by Islamic invasions. Khayal is possibly one of the finest creations to emerge from the melting pots of Hindu and Muslim imaginations.

Origin and Development of Khayal

The emergence of khayal can be attributed to the 12th or 13th centuries, during the growth of Islam in India. The newly arrived Muslim rulers were just spell-bound by the diversity of North Indian music and its singers. Dhrupad, during that time, was already an established form of musical genre, to which was added Persian and Arabic tinges. Thus, dhrupad took a backseat, and khayal emerged in all its splendour. Most khayal gharanas are known to have evolved from old dhrupadi gharanas, thus sometimes referred to as the offspring of dhrupad. Some of the evidence point out that khayal might have improvised from Amir Khusro, the legendary Persian musician. However, it was not until the rise of the Mughals, that khayal came into full vogue. Mohhamed Shah can be called the propagator of this classical musical genre, who much enthusiastically endorsed khayal in his court. A fascinating story of court instrumentalist Niyamat Khan, is recited here in this regard, who was another individual behind the evolving of khayal. Gradually, khayal caught the air of contemporaneity, and innovative themes, like alaap, raaga, taan, or bol-taan were introduced. And singers took to it this rhythmic singing with much gusto.

The emergence of khayal can be attributed to the 12th or 13th centuries, during the growth of Islam in India. The newly arrived Muslim rulers were just spell-bound by the diversity of North Indian music and its singers. Dhrupad, during that time, was already an established form of musical genre, to which was added Persian and Arabic tinges. Thus, dhrupad took a backseat, and khayal emerged in all its splendour. Most khayal gharanas are known to have evolved from old dhrupadi gharanas, thus sometimes referred to as the offspring of dhrupad. Some of the evidence point out that khayal might have improvised from Amir Khusro, the legendary Persian musician. However, it was not until the rise of the Mughals, that khayal came into full vogue. Mohhamed Shah can be called the propagator of this classical musical genre, who much enthusiastically endorsed khayal in his court. A fascinating story of court instrumentalist Niyamat Khan, is recited here in this regard, who was another individual behind the evolving of khayal. Gradually, khayal caught the air of contemporaneity, and innovative themes, like alaap, raaga, taan, or bol-taan were introduced. And singers took to it this rhythmic singing with much gusto.

Its exact origins, to a certain extent, are shrouded in mystery and apocrypha, a fact further made difficult by the present poor record-keeping skills. The arrival of Islam from the 12th and 13th centuries onwards, and shifts in the nature of patronage, undoubtedly, brought about noteworthy alterations in the musical culture of North India. Fascinated as some of the Muslim rulers and musicians were by the structure and solidity of the North Indian musical tradition, they nonetheless decided to intersperse it with new and `exotic` airs. The Indian musicians of the time compiled with the cultural and aesthetic demands made by their new patrons. In the process of cultural co-mingling that took place from the 13th to the mid-18th centuries, many raagas and styles of musical renderings took on Persian, Arabic and Turkish hues. The outcome of this lovely aesthetic synthesis and gradual transformation that took place over long periods of time was the khayal.

Indeed, khayal is the offspring of dhrupad. Some of the first khayals, composed and rendered by singer-composers of older gharanas, resemble dhrupad bandishes in that they are melodically well-structured and rhythmically coordinated along dhrupadic lines. Older khayal gharanas, like Agra and Jaipur, are, in essence, dhrupadic. In fact, most khayal gharanas claim to have originated from some pre-existing dhrupadic tradition or the other. While some of these claims are genuine, others have been fabricated by those hailing from non-dhrupadic roots to enhance their musical pedigree and prestige.

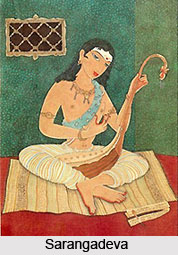

A certain school of thought would have one believe that the celebrated Persian musician-poet Amir Khusro (1254-1325) was the progenitor of khayal. It is assumed that Khusro, who was a disciple of the Sufi saint Hazrat Nizammudin Aulia, absorbed the qwaali style of singing from the Sufis and interchanged it onto the existing musical structure. This story remains unproven by convincing historical evidence. Later, khayal is said to have developed in the court of the musician-patron Sultan Mohammed Sharqui of Jaunpur (1457-1476). But the form as such existed until the 18th century in a somewhat crude and indefinite form.

It was not until the time of the Mughal ruler, Mohammed Shah `Rangile` (1719-1748) that the khayal, as one knows it, shot into prominence. It is believed that one of the court instrumentalists, Niyamat Khan, took offence when he was seated behind the singers in the darbar and gave up his position. Determined to make his mark in the field of music, he went about improvising the embryonic khayal form and brought it to perceptible perfection. He then trained two young boys exhaustively in the new form. After completing their formal training, the two boys began singing the newly sprung khayal before awe-struck audiences who had heard nothing like it previously. Their vocal prowess and charming approach, soon enough, came to Mohammed Shah`s notice. He invited them to be court musicians after he heard their extraordinary performance. When asked about their teacher, the boys divulged the long-withheld identity of Niyamat Khan to the astounded ruler. The chastised ruler, certain of Niyamat Khan`s intellect, invited him to occupy a coveted seat in the darbar alongside the court singers. Niyamat Khan is reputed to have penned umpteen exquisite khayal compositions under the pen name, `Sadarang` (standing for `ever-colourful`) which are sung even today by khayal singers. Sadarang trained many disciples in the new form. His nephew, Firoz Khan also made momentous contributions to the form. He wrote compositions under the pen name `Adarang`. Though they trained countless to sing khayal, it is rumored that they themselves never took to it.

What both Sadarang and Adarang did, for the most part, was to build new melodic structures on the foundations of dhrupad. There were some substantial departures from the parent form. The long alaap which preceded the composition was smoothly incorporated into its structure. Different elements and facets of the raaga, expressed separately in the unmetered and metered sections in slow and fast tempi were now expressed within the canopy of a single unit. In terms of compositions, khayal offered a wider variety of themes for exploration and the means to express them through creative means. The myriad shades and colours of hallowed and romantic love, the feats of Krishna as an infant, lover and saviour, descriptions of the diverse seasons and articulations of intense veneration formed, for the most part, the subjects of khayal compositions.

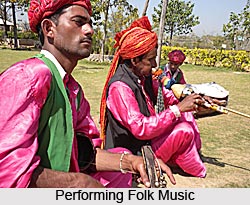

Unsurprisingly, the new form caught fancy of several contemporary singers. It offered them, on the one hand, the solid classical base of dhrupad, and, on the other, a new scope for exploring a variety of moods and emotions within a classical framework. By the end of the 18th century, the potent `upstart` khayal had thrust the stolid elder statesman, dhrupad, out of the field to become the most popular of classical forms in North Indian classical music. Soon enough, fresh additions, like the use of sargams, tans and bol-taans and adoptions of idioms from lighter forms like tappa and thumri added to its technical finesse and emotional articulateness. Creative variations of words in the song-text were possible in a less rigid manner. Put simply, the khayal became more fluid and flexible, yet without compromising on its classical ethos or structure. It lost not a speck of its classical roots even as its enormous trunk shot skywards, sprouting new leaves and broad branches. Today, the khayal is one of the most vivacious and variegated of classical forms which has both imbibed and integrated the distinctive features of most major classical, light classical and folk forms into its voluminous bosom. Once a tiny drop, with the passage of time, it added to its width and depth from plentiful diverse streams to become what it is today - an unending and mighty river of melody.

Types of Khayal

Types of khayal in Indian Classical Music are mainly of two types. These are the bara khayal and the chhota khayal. The two types of khayal performance are distinguished primarily by the basic level of speed at which they are sung and by the type of improvisation that follows the chiz. Bara khayal is sung in slow speed (vilambit laya) or medium speed (madhya laya). In slow speed, each count of the tala is divided into four beats; this can be heard clearly in the tabla part. In medium speed, each count of the tala is either subdivided into two beats or receives one beat. Chhota khayal is always in fast speed. It receives one beat per tala count but moves at a much faster clip than medium speed. Bara khayal is usually in tintal, tilwara tal, ektal, jhumra tal, or jhaptal; chhota khayal are almost invariably in tintal or ektal.

Types of khayal in Indian Classical Music are mainly of two types. These are the bara khayal and the chhota khayal. The two types of khayal performance are distinguished primarily by the basic level of speed at which they are sung and by the type of improvisation that follows the chiz. Bara khayal is sung in slow speed (vilambit laya) or medium speed (madhya laya). In slow speed, each count of the tala is divided into four beats; this can be heard clearly in the tabla part. In medium speed, each count of the tala is either subdivided into two beats or receives one beat. Chhota khayal is always in fast speed. It receives one beat per tala count but moves at a much faster clip than medium speed. Bara khayal is usually in tintal, tilwara tal, ektal, jhumra tal, or jhaptal; chhota khayal are almost invariably in tintal or ektal.

Bara khayal improvisation resembles the alap that precedes dhrupad: it begins slowly, explores the raaga in low register first, then moves upward. Although the tala is kept by the tabla player, who repeats and repeats the theka, and although the singer certainly knows where (s)he is in the tala cycle, the rhythm seems free and floating, as in unmetered alap. The recurrence of the mukhra functions as the mohra does in pre-dhrupad alap. Rather than singing vocal syllables, as in dhrupad alap, the singer uses the chiz text (the improvisation using the text is then called bolbant) or vowels. (S)he is usually careful not to use the text rhythmically, however, so (s)he changes syllables off the counts, says the words indistinctly, and sings many pitches to a single syllable. As the performance progresses, (s)he begins to lean to rhythm by interspersing in the improvisation passages of boltan, tans, and occasionally sargam. Passages of sargam use the solfege syllables as text. As a pitch is sung, it is named. The text enunciation emphasizes rhythm. Bolbant is considered a carry-over into khayal from dhrupad. It consists of a long phrase or sentence from the chiz text that is played upon to primarily rhythmic effect. The emphasis on the text in bolbant provides marked contrast with the wide use of vowels only (akar), in much khayal improvisation.

As a bara khayal performance progresses, more and more tans are sung. Tans are very fast melodic figures that may (or may not) touch pitches not in the particular raaga. They are borne on the vowels of text syllables or on independent vowels.

As a bara khayal performance progresses, more and more tans are sung. Tans are very fast melodic figures that may (or may not) touch pitches not in the particular raaga. They are borne on the vowels of text syllables or on independent vowels.

Chhota khayal is rarely performed as a distinct entity. Usually, it follows a bara khayal, in the same raga but often in a different tala, without break as a continuation of the acceleration of the bara khayal. The chhota khayal chiz is presented quickly, and improvisation continues. Alap-type exploration of the raga can be dispensed with since it was present in the bara khayal. Chhota khayal improvisation is characterized by rapid passage work (tans), many repetitions of the first phrase of the sthal, a generally rhythmic orientation, and constant acceleration.

Occasionally, a khayal singer will substitute another form for the chhota khayal; the sequence will be bara khayal to tarana. The major difference between chhota khayal and tarana lies not in the composition, nor in the performance treatment, but in the text. Vocables are the major text rather than verse or prose, as in chiz. However, a tarana can sometimes include a a Persian couplet, but the couplet does not function as a chiz functions in khayal. One school of thought holds that the various combinations of vocables in tarana are not just meaningless vocables but are Persian word. Such poetry is said to be representative of the mystic school of poets, in which the beloved is the Almighty and the devotee is his lover. Thus, the poetry of tarana is spiritual, though romantic.

Some sources on Indian music say that pakhavaj bols are introduced into tarana as text, and indeed that does happen. The other vehicle for melody here is sargam (solfege syllables). Tarana are usually performed by artists who specialize in them. Nissar Hussain Khan, the late Amir Khan, and Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit are particularly well known for performance of tarana. To sing tarana requires skill in rhythmic manipulation Qayakari) and the ability to sing syllables rapidly. The Carnatic version of tarana, which is called tillana, is very similar and is said to have developed at about the same time.

Melody of Khayal

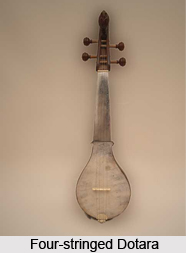

Khayal is the modern genre of classical singing in North India. Khayal is the outcome of the incorporation of two cultures. Melodic execution in Hindustani music, essentially, avoids abruptness in intervallic transitions. The theory of music performance narrates at least ten forms of melodic execution or intervallic transitions. Other texts have larger accounts. The definitions from the texts are indefinite and also vary from text to text. The categories of melodic contours encountered in contemporary Khayal performance would, however, outnumber all inventories considered together.

The principle categories of intervallic transition or melodic expressions are as follows:

Minda: Minda is the basic form of intervallic transition in Khayala music. It involves a melodically continuous dragging of one svara to another, touching all the microtones along the path.

Kan: The word Kan means "fraction." When an intervallic transition between svaras involves a fractional use of the first svara, it is called a kan. A generous use of the kan is considered more appropriate in the semi-classical Thumri renditions than in Khayal.

Murki: Murki is used more generously in the Thumari genre. Murki involves the execution of a phrase normally using at least three svaras quickly, wrap-around, jerky expression, as in pa-maA-dha-pa. Single-loop murkis are used in the khayala genre while multiple-loop murkis are used, in the Thumri genre.

Gitakiri: The brisk and precise intonation of three or more adjacent svaras, whether in ascent or crescent, without a jerk or wrap-around melodic motion, is called a gitakiri.

Khataka: The word Khataka means `a jerk". This melodic expression is generally used for a transition between svaras and in descending transition. The expression descends from the higher svara to the lower svara, with a jerk. This is especially useful in ragas like Gaud Sarang. The sa-pa and pa-re transitions in Gaud Sarang employ the Khataka expression.

Gamaka: The Gamaka expression evolves from the repetition of the same svara at a medium-to-high svara-density. The musicians take the help of the lower svara without its explicit intonation. The musicians beat the target svara to create the gamaka expression.

Jatnajama: This expression also uses two adjacent svaras. One is emphasized by repetition and differs from the gamaka in that the jamajama explicitly intones both the adjacent svaras, as in ga-ma-ma/ga-ma-ma/ga-pa-pa/ma-pa-pa.

These categories of melodic expression define the sculptural features of a vocal recital. Gharanas, and individual musicians, differ in their preferences in this regard. These preferences, collectively, constitute a major part of the "stylistics" of Khayala music.

Articulation in Khayal Music

Khayal is a semi-classical genre of singing that originated from the courts of royals in Awadh. Most khayal singers are "of a gharana," and there are numerous khayal gharanas. Gharanas are customarily named after a place where the family of musicians originated or where they developed their style, for example, Kirana, Agra, Jaipur, and Gwalior. The khayala genre deploys three categories of articulation:

[a] Bola: The poetic form, representing a vast range of themes, which binds together the melodic and rhythmic elements in the composition.

[b] Saragama: The use of solfa symbols as textural consonants in the improvisatory movements.

[c] Akara: The vowel a used in the improvisatory movements.

These three forms of articulation play collective, as well as individual, roles in the performance of khayala compositions. At the purely phonetic level, they provide the musician with three distinct textural devices. The saragama device uses only consonants, and the range is limited to seven. The akara has only one vowel, though individual styles can occasionally vary the articulation slightly.

The three forms of articulation also symbolize three different levels of abstraction in terms of meaning. The saragama represents musical meaning, by virtue of direct correspondence between the intonation and the articulation. The akara, being a vowel phonetic, is totally abstract, with the meaning being provided only by the melodic contours of the intonation. The use of the three forms of articulation is guided by aesthetic considerations, and by the stylistic inclinations of individual gharanas and vocalists.

The saragama is used mainly in medium density movements. In such movements, it offers a textural selection for the poetic form. It tends not to be used in very high-density melodic movements because consonants militate against high-frequency articulation. The Akara articulation is the most versatile. Being a vowel form, it is most useful in movements where the melody is not required to express much rhythm. Such movements are the low srara-density alapa and the high-density tanas.

Form and Structure of Khayal

Essentially, a khayal consists of a composition (chiz) of two sections- sthai and antara- and extensive improvisation. It differs from dhrupad in one significant way: no lengthy unmetered alaap precedes the singing of the composition, except in the Agra Gharana. Singers introduce the raaga for a few seconds, and occasionally, for as long as five minutes. But the exposition of the pitches rarely exceeds pitch Pa of the middle octave and is often merely an anticipation of the melody of the chiz. Since the chiz is sung immediately, and since all chiz are metered songs, all of the improvisation in khayal is metered and accompanied on the tabla. The chiz is very short. It presents in song form the characteristics of the raaga and tala in which it is composed. In particular, the first section of the chiz, the sthai, states the melodic bundle of the raga. The second section of most chiz, the antara, are very similar in shape, ascending to tar Sa in a manner peculiar to the raaga, going higher into the upper octave, then descending to link with the sthai again. The antara section of a chiz is frequently omitted altogether, which reduces the composed portion of the performance to one or two tala cycles of sthai. The entire presentation of the chiz takes a very small amount of time, usually no more than five minutes of the half-hour to forty minutes of performance time. Khayal singers avoid enunciating the words clearly, except in bolbant. This is often cited as a major difference between Khayal and dhrupad, in which every syllable must be clear. This characteristic, and perhaps others, tends to make Khayal the most difficult classical vocal medium to interpret.

Gharanas of Khayal

Most Khayal singers are "of a Gharana," and there are numerous Khayal Gharanas. Gharanas are customarily named after a place where the family of musicians originated or where they developed their style, for example, Kirana, Agra, Jaipur, and Gwalior. A number of Gharanas sprouted in several parts of North and Central India, towards the end of the 19th and the beginning of the 20th century. A considerable number of them came into being, owing to breaches and fissions between occurring in a parent Gharana. A musical tradition is generally considered "of a Gharana" when at least three successive generations of able musicians have pursued a distinctive style of singing. Part of the style is the quality of voice that is cultivated. Consequently, vocal training is developed to help successive members of the Gharana cultivate that vocal quality. Thus in Kirana, the voice emerges from a deliberately constricted throat and has a nasal twang. An Agra voice is also nasal (nakki); in addition it has a gruff, grating quality. On the other hand the Jaipur tradition emphasizes a natural, free and full-throated voice.

Khayal in Modern Era

Modern khayal is quite young in age. In fact it has gained in popularity over the Dhrupad. The several Khayalas composed by Sadaranga Adaranga, followed by many more, have become a rather popular genre in Indian Classical Music. Gwalior which was the nursery of the Dhrupad-Dhamar in the times of the Sindhias, became the main patron of the Khayal and Bade Mohammed Khan, Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan received their patronage from the Gwalior rulers. In fact the rise of Gharanas in Hindustani can be attributed to the several musicians who were trained within and outside their clan. The freedom of expression has been one of the major factors that have helped the Khayal gain in currency and sustained it as a popular genre. The Khayala received great impetus during the times of Mohmmed Shah Rangile and in the Gwalior tradition it came to the forefront. Professional musicians trained their sons and relations in the art. Most of the later Gharans mark or draw their genealogy back to the renowned Haddu Khan or Hassu Khan, the names which stand for the Gwalior Gharana.