Introduction

Tappa, understood to have been the staple diction of the erstwhile camel drivers, has since come to a ripened age, by being nurtured in the hands of some of the legendary masters in this genre. The word Tappa stands for jumping, bouncing and skipping, implying the extraordinary rule of unremitting attempts made by a singer on the musical notes, not stopping or taking a pause for once. This outstanding formation is unique to tappa only, absent in the other Hindustani classical forms. It is thus composed of rhythmic and rapid notes, and such a style calls for immense and extreme hold over the singing diction. A contrary to which can damage the whole recital. Tappa is very unlike khayal rendition, crisp and highly volatile in its nature. And the few exponents like Ghulam Nabi, Pt. Bholanath Bhatt or Girija Devi have thus become legends in their own right.

Tappa, understood to have been the staple diction of the erstwhile camel drivers, has since come to a ripened age, by being nurtured in the hands of some of the legendary masters in this genre. The word Tappa stands for jumping, bouncing and skipping, implying the extraordinary rule of unremitting attempts made by a singer on the musical notes, not stopping or taking a pause for once. This outstanding formation is unique to tappa only, absent in the other Hindustani classical forms. It is thus composed of rhythmic and rapid notes, and such a style calls for immense and extreme hold over the singing diction. A contrary to which can damage the whole recital. Tappa is very unlike khayal rendition, crisp and highly volatile in its nature. And the few exponents like Ghulam Nabi, Pt. Bholanath Bhatt or Girija Devi have thus become legends in their own right.

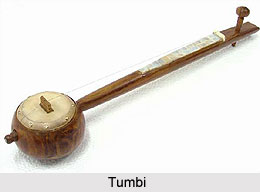

It is usually held that tappa is derived from the songs and tunes sung by the camel drivers of North West Punjab. These songs were composed in Punjabi and Pusthu and, like thumri, were amatory in spirit. The word tappa is derived from the root word tap, which means to `jump`, `bounce`, or `rebound` in the manner of a bouncing ball.

The artists who popularised this style include Pt. Laxmanrao Pandit of Gwalior, Shanno Khurana, Pt. Manvalkar of Gwalior, Girija Devi of Benaras, Dr. Ishwarchandra R. Karkare of Gwalior, Smt. Malini Rajurkar, Shri Sharad Sathe, Manjiri Asnare Kelkar of Jaipur-Atrauli Gharana and Pandit Yashpaul of the Agra Gharana.

History of Tappa

History of Tappa outlines the biographical sketches included in the epic work of Indian Music, by Dr. Thakur Jaydev Singh.  According to him, Shorie Miya had four significant disciples: Prasiddhu Maharaj, Miya Gammu or Gammu Khan, Tarachand, and Mir Ali Saheb, Gammu Khan`s son, Sadi Khan and Babti Ramsahay. He is considered as a member of the kathaka community who together with his brother Manohar Maharaj founded the Prasiddhu-Manohar lineage. Like the other lineages of Tappa singers, this lineage asserted significant musicianship in the mainstream genres of vocal music. Prasiddhu`s great-grandson, Ramkrishna Mishra taught and performed in Kolkata till 1955.

According to him, Shorie Miya had four significant disciples: Prasiddhu Maharaj, Miya Gammu or Gammu Khan, Tarachand, and Mir Ali Saheb, Gammu Khan`s son, Sadi Khan and Babti Ramsahay. He is considered as a member of the kathaka community who together with his brother Manohar Maharaj founded the Prasiddhu-Manohar lineage. Like the other lineages of Tappa singers, this lineage asserted significant musicianship in the mainstream genres of vocal music. Prasiddhu`s great-grandson, Ramkrishna Mishra taught and performed in Kolkata till 1955.

History of Tappa outlines the biographical sketches included in the epic work of Indian Music, by Dr. Thakur Jaydev Singh. According to him, Shorie Miya had four significant disciples: Prasiddhu Maharaj, Miya Gammu or Gammu Khan, Tarachand, and Mir Ali Saheb, Gammu Khan`s son, Sadi Khan and Babti Ramsahay. He is considered as a member of the kathaka community who together with his brother Manohar Maharaj founded the Prasiddhu-Manohar lineage. Like the other lineages of Tappa singers, this lineage asserted significant musicianship in the mainstream genres of vocal music. Prasiddhu`s great-grandson, Ramkrishna Mishra taught and performed in Kolkata till 1955.

Gammu Khan`s son, Sadi Khan had left Lucknow to settle in Varanasi. The city thus became an early partner in the evolution of the genre. Sadi Khan`s presence encouraged the leading courtesans of the era to master the art. The Prasiddhu-Manohar lineage was also initiated in the city that made a significant impact in the propagation of Tappa. Throughout the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, the courtesans of Varanasi remained important repositories of the Tappa art. Of great importance to the surviving Tappa tradition of Varanasi are the names of Bade Ramdasji who was born on 1896. He was a prominent Khayal singer who trained several famous twentieth-century vocalists in the Tappa.

The tappa entered the Gwalior Khayal lineage early in its history during the nineteenth century. Natthan Peer Baksh was the founder of the Gwalior lineage. He had studied the Tappa with Shakkar Khan and Makkhan Khan, two famous disciples of Shorie Miya`s father, Ghulam Rasool. Natthan Peer Baksh` grandsons, Haddu Khan and Hassu Khan apparently adopted the tappa into the gharana`s collection. Haddu Khan`s son, Rehmat Khan was a formidable tappa singer. Haddu Khan`s son-in-law, Inayet Hussain Khan, founder of the Sahaswan-Rampur gharana of the khayala, and his heirs, Mushtaq Hussain and Nissar Hussain, were also eminent tappa performers.

Hassu Khan`s disciples, Devji Buwa, and Raoji Buwa carried on the tappa tradition in the Gwalior lineage. In the succeeding generation, Balkrishna Buwa Ichalkaranjikar brought the tappa into the khayala mainstream in Maharashtra. Narayan Buwa Phaltankar on the other hand introduced the tappa style to the performance of abhangas. With their contribution, the tappa genre struck deep roots in the cultural soil of Maharashtra. The Gwalior khayala lineage values its tappa repertoire as a means of cultivating exceptional vocal agility.

Through the nineteenth century, Lucknow remained active in the tappa genre, with Nawab Hussain Khan [died early nineteenth century], and Chhajju Khan [died 1870] on record as great practitioners of the art. In the late nineteenth century, eastern India exhibited great enthusiasm for the genre, with the performing and scholarly contributions of Gopeshwar Bannerji of Vishnupur Raja Sourendra Mohan Tagore of Jorasanko, and Bholanath Bhatt of Darbhanga Gwalior also remained an important centre of the tappa well into the twentieth century, with Balasaheb Guruji and his disciple Nanu Bhaiyya Telang distinguishing themselves.

Features of Tappa

The form itself, with its rapid movements, gives the impression of a briskly hopping ball. Singers attempt to capture these rapid rhythms by hopping from one note to the next, without respite. The song-text is very short and not as elaborately structured as a khayal or a thumri. Singers render it crisply and concisely. One of its most striking features is the singer`s use of an unrelenting cascade of jumpy and zig-zag taans called zamzama. Being a highly unpredictable style, the singer cannot, and should not, rest on any of the notes the way khayal and thumri singers do. He or she has to persistently hop from one note to the next improvising as he or she goes along using varieties of taans, which are not used in khayal. Unnecessary to say, this breathless form demands a great mastery over melodic and rhythmic aspects, as the singer has to improvise continually.

The features of Tappa are varied and are usually based on the way it deals with the notes. The identifying feature of the Tappa is the way it treats the melody. The melody is not only vivacious and mischievous but also relates to the beats of the rhythmic cycle. The important feature to achieve the melodic sparkle of the Tappa is those strings of intricate symmetric phrases creating brisk tana. A Tappa is easily identifiable for its distinct music.

The features of Tappa are varied and are usually based on the way it deals with the notes. The identifying feature of the Tappa is the way it treats the melody. The melody is not only vivacious and mischievous but also relates to the beats of the rhythmic cycle. The important feature to achieve the melodic sparkle of the Tappa is those strings of intricate symmetric phrases creating brisk tana. A Tappa is easily identifiable for its distinct music.

Composition of Tappa

Tappas are composed mainly in Thumri raagas, such as Bhairavi, Khamaja, Desa, Kafi, Jhinjhoti, Pilu, Barwa. They are generally set to 16-beat variants of the tinatala, such as addha, qawwali and sitarakhani. A few Tappas have also been composed in ekatala. Tappas are sung in medium tempo in ekatala as well as tinatala. The lyrics are mostly in Punjabi or Sindhi languages and centred on the tragic romance of Hir and Ranjha. This is an important part of the folklore of the Punjab region. Shorie Miya included general romantic themes, and also philosophical themes in his Tappas. His compositions are still popular among his followers.

Tappa lyrics are short, either two lines or two stanzas with two short lines each. Many Tappa songs also have a separate manjha section between the sthayi and the antara. A Tappa is generally associated with the poetic-melodic form as its basic material. Akara tanas and bola-banta or layakan which are of the Khayal variety are not found in the Tappa. Its bola-tanas are associated with the lyrics. The symmetry of Tappa taanas is typically expressed in overlapping ascending or descending waves of phrases. This symmetrical pattern may sometimes include shifts of svara density. The special feature of Tappa is the looped or bi-directional phrases used to build the melody. This feature is best exploited in highly malleable ragas like Bhairavl, and Kafi.

Although, the Tappa apparently relied on the bandisa thumari and the chota khayala for its format, it has, in turn, influenced the khayala genre by giving birth to a hybrid form, the tap-khayala. This form is normally rendered in the "classical" ragas, but has the distinct vivacity of the Tappa in its treatment of melody.

Performers of Tappa

Some of the great exponents of tappa in this century are Pt. Bholanath Bhatt, Siddheshwari Devi and Girija Devi. The doyens of Gwalior gharana, Pt. Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit and Saratchandra Arolkar were known to sing it in a slow and unhurried pace. In the post-Independence era, it was Pt. Kumar Gandharva who played a substantial role in popularizing this form. Today, Malini Rajurkar is the only singer of repute who has made tappa an essential item in her concert repertoire and also renders it memorably.

Tappa in Modern India

Tappa is seldom heard in concert circuits these days, as it is a highly demanding and difficult style to master. Also, the number of singers capable of rendering it competently has declined abruptly in the recent past. Tappa is most definitely on the `endangered` list of musical forms. Yet, many singers and instrumentalists have freely borrowed and continue to borrow the brisk embellishments like zamzama. Some gharanas have even gone to the extent of combining tappa with khayal, to give rise to an amalgamated form known as tapkhayal.

Tappa musicianship had its major influence in the courtesan tradition of Varanasi. Tappa is a form of Indian semi-classical vocal music. Tappa is a light classical style which is declining in popularity. It is basically a classical style of music from the Punjab. This specialized in the semi-classical genres such as the thumri, dadra, caiti and kajan, along with the allied folk-based genres of the region.

Tappa musicianship had its major influence in the courtesan tradition of Varanasi. Tappa is a form of Indian semi-classical vocal music. Tappa is a light classical style which is declining in popularity. It is basically a classical style of music from the Punjab. This specialized in the semi-classical genres such as the thumri, dadra, caiti and kajan, along with the allied folk-based genres of the region.

The other significant repository of Tappa musicianship is the Gwalior Khayala Gharana. From the second quarter of the twentieth century this Gharana was on a decline. In order to re-invent itself, it however shifted towards the aggressive, rhythm-oriented, vocalism of the Agra Gharana. One of the results of the Gwalior-Agra Gharana confluence was the gradual disappearance of the Tappa from Gwalior repertoire. The Khayal Gharanas, that gained dominance in the post-Independence era, chiefly Kirana and Jaipur-Atrauli, ignored the tappa. It favoured much the thuman or bhajanas.

Presently Tappa can claim the presence of Girija Devi born on1929 and Shobha Gurtu born on 1925. They are the specialists of the semi-classical genres who have excelled at Tappa rendition. Amongst established khayala vocalists, the significant tappa exponents are Laxman Krishnarao Pandit who was born on 1932 and Malini Rajurkar who was born on 1941.

Some of the great exponents of tappa in this century are Pt. Bholanath Bhatt, Siddheshwari Devi and Girija Devi. The doyens of Gwalior gharana, Pt. Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit and Saratchandra Arolkar were known to sing it in a slow and unhurried pace. In the post-Independence era, it was Pt. Kumar Gandharva who played a substantial role in popularizing this form. Today, Malini Rajurkar is the only singer of repute who has made tappa an essential item in her concert repertoire and also renders it memorably.

Some of the great exponents of tappa in this century are Pt. Bholanath Bhatt, Siddheshwari Devi and Girija Devi. The doyens of Gwalior gharana, Pt. Krishna Rao Shankar Pandit and Saratchandra Arolkar were known to sing it in a slow and unhurried pace. In the post-Independence era, it was Pt. Kumar Gandharva who played a substantial role in popularizing this form. Today, Malini Rajurkar is the only singer of repute who has made tappa an essential item in her concert repertoire and also renders it memorably.

Another singer Manjiri Asnare Kelkar born on 1971 is also a successful khayala vocalist who is credited with reviving a constituency for the Tappa. Her introduction into this genre is quite interesting. Manjiri belongs to a thoroughbred Maharashtrian family, and had her initial training in the Gwalior tradition. During her early days she became a fan of Malini Rajurkar, especially because of her tappa renderings. She obtained all available tappa recordings of Malini and started performing them with great success. However later she became a disciple of Madhusudan Kanetkar, the Jaipur-Atrauli gharana stalwart, who studied the Tappa specially to be able to help her organize and polish her renditions. Thus Manjiri`s success with the Tappa confirms several promising features of the genre.