Bengal Renaissance

British India had brought together with their Occidental culture a new domain towards betterment in life, a breakaway from dark fashion. `Renaissance` was that very domain that had infused India to its core, courtesy the reformist thinkers and intellectuals born prior to independence. And Bengal during those times was the pinnacle of culture and heritage, with the maximum of writers and fighters being bred from that part of eastern India. As such, Bengal was the foremost region which was inspired from their European counterpart in the renaissance and `reawakening` regard. Bengal Renaissance refers to a massive social reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the region of Bengal in undivided India during the extensive period of British supremacy. In Bengal, the five fundamental influences led to the tremendous emergence of Bengal Renaissance, comprising; the boost of British-Bengali commerce, the introduction of English education, British Orientalism, Christianity and perhaps above all, how the Bengali intellectuals themselves responded to these influences.

The East India Company took control of Bengal, Bihar and parts of Orissa in 1765 from Shah Alam, the Mughal Emperor. As a result, Bengal and its environing lands became the first neighbourhoods in India to encounter the direct impact of British rule and the beginnings of modernisation. For the remaining eighteenth century and throughout the early decades of nineteenth century, the British laid solid foundations for civil administration. They laid down communication and transportation systems, a modern bureaucracy, an army and a police. They further established law courts and opened schools and colleges. The nineteenth century became the high point of British-Indian mutual reciprocation, especially within Bengal. Historians denote this era as the Bengal Renaissance, a period of passionate cultural and technological advancement, as well as a time of great social, cultural, and political metamorphosis.

British India had brought together with their Occidental culture a new domain towards betterment in life, a breakaway from dark fashion. `Renaissance` was that very domain that had infused India to its core, courtesy the reformist thinkers and intellectuals born prior to independence. And Bengal during those times was the pinnacle of culture and heritage, with the maximum of writers and fighters being bred from that part of eastern India. As such, Bengal was the foremost region which was inspired from their European counterpart in the renaissance and `reawakening` regard. Bengal Renaissance refers to a massive social reform movement during the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries in the region of Bengal in undivided India during the extensive period of British supremacy. In Bengal, the five fundamental influences led to the tremendous emergence of Bengal Renaissance, comprising; the boost of British-Bengali commerce, the introduction of English education, British Orientalism, Christianity and perhaps above all, how the Bengali intellectuals themselves responded to these influences.

The East India Company took control of Bengal, Bihar and parts of Orissa in 1765 from Shah Alam, the Mughal Emperor. As a result, Bengal and its environing lands became the first neighbourhoods in India to encounter the direct impact of British rule and the beginnings of modernisation. For the remaining eighteenth century and throughout the early decades of nineteenth century, the British laid solid foundations for civil administration. They laid down communication and transportation systems, a modern bureaucracy, an army and a police. They further established law courts and opened schools and colleges. The nineteenth century became the high point of British-Indian mutual reciprocation, especially within Bengal. Historians denote this era as the Bengal Renaissance, a period of passionate cultural and technological advancement, as well as a time of great social, cultural, and political metamorphosis.

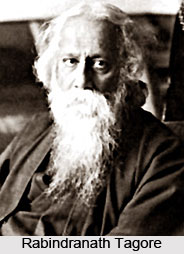

With the consolidation of British political power in India came the ascension of extensive trade and the establishment of large centres of administration and business. Calcutta in particular became the focus of British administration, trade and commerce. In the process a class of Bengali elite germinated that could mingle with the ruling British. This was the bhadraloka, a `socially privileged and consciously superior group`, economically dependent upon landed rents, professional and clerical employment. During the second half of eighteenth century, this elite group started to reside in Calcutta as permanent residents. Some from this `elite` bunch hurriedly acquired fortunes by working in partnership with the British. Bengal renaissance can be declared to have commenced precisely from this bunch, which including among other legends, started with Raja Ram Mohan Roy (1775-1833) and ended with Rabindranath Tagore (1861-1941). Nineteenth century Bengal was an unparalleled mish-mash of religious and social reformers, scholars, literary heavyweights, journalists, patriotic orators and scientists, all coalescing to form the image of a renaissance.

During the period designated as Bengal renaissance, Bengal witnessed an intellectual awakening that was in some way similar to the Renaissance in Europe during the 16th century. Indian renaissance severely questioned the existing orthodox customs, especially with respect to women (sati for instance), marriage, the dowry system, the caste system and religion. One of the earliest social movements that emerged during this time was the Young Bengal movement, that adopted rationalism and atheism as the common attributes of civil conduct among upper caste cultivated Hindus.

The Brahmo Samaj, the parallel socio-religious movement had germinated during this time and banked upon many of the leaders of Bengal Renaissance amongst its followers. Their version of Hinduism, or rather Universal Religion (likened to that of Ramakrishna), was entirely devoid of practices like sati and polygamy that had crept into the social aspects of Hindu life. Hinduism according to Brahmo Samaj was an unyielding impersonal monotheistic faith, which actually was quite dissimilar from the pluralistic and comprehensive nature of the way Hindu religion was practiced. Future leaders like Keshab Chandra Sen were as much devotees of Christ, as they were of Brahma, Krishna or Buddha. The renaissance period after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, witnessed an outstanding overflow of Bengali literature. While Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar were the pioneers, others like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee broadened it and built upon it. The first significant nationalist detour to the Bengal Renaissance was given by the splendid writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Later writers of the British Indian period, who introduced panoptic discussions of social problems and more colloquial forms of Bengali into mainstream literature, included the great Sarat Chandra Chatterjee.

The Brahmo Samaj, the parallel socio-religious movement had germinated during this time and banked upon many of the leaders of Bengal Renaissance amongst its followers. Their version of Hinduism, or rather Universal Religion (likened to that of Ramakrishna), was entirely devoid of practices like sati and polygamy that had crept into the social aspects of Hindu life. Hinduism according to Brahmo Samaj was an unyielding impersonal monotheistic faith, which actually was quite dissimilar from the pluralistic and comprehensive nature of the way Hindu religion was practiced. Future leaders like Keshab Chandra Sen were as much devotees of Christ, as they were of Brahma, Krishna or Buddha. The renaissance period after the Sepoy Mutiny of 1857, witnessed an outstanding overflow of Bengali literature. While Ram Mohan Roy and Ishwar Chandra Vidyasagar were the pioneers, others like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee broadened it and built upon it. The first significant nationalist detour to the Bengal Renaissance was given by the splendid writings of Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Later writers of the British Indian period, who introduced panoptic discussions of social problems and more colloquial forms of Bengali into mainstream literature, included the great Sarat Chandra Chatterjee.

Later, Ramakrishna Paramahansa, the legendary saint from Bengal, is believed to have recognized the mystical truth of every religion and to have harmonised the conflicting Hindu sects ranging from Shakta tantra, Advaita Vedanta and Vaishnavism. In fact Ramakrishna made famous the Bengali saying: "Jato Mat, Tato Path" (All religions are different paths to the same God). The Vedanta movement flourished principally through his disciple and sage, Swami Vivekananda. He was one of the leading intellectuals who had carried the torch of Bengal Renaissance towards the dazzling future of swaraj. On Vivekananda`s return from the highly acclaimed Parliament of the World`s Religions in Chicago in 1893 and subsequent lecture tour in America, he had become a revered national idol. Ramakrishna Mission, the great organisation founded by Swami Vivekananda, was wholly non-political in nature. It must be stressed that the Ramakrishna Movement founded by Swami Vivekananda carried forward their Master`s (Ramakrishna`s) message of all religions being true.

Next to this illustrious line of Bengalis, the Tagore family, including Rabindranath Tagore, were leaders of this period and shared a meticulous interest in educational reforms. Their contribution to Bengal Renaissance was multi-faceted and indeed priceless. Tagore`s 1901 Bengali novella, Nastanirh was penned as a critique of men who conceded to follow the ideals of Bengali Renaissance, but were unsuccessful to do so within their own families. Tagore`s English translation of a set of poems titled the Gitanjali won him the Nobel Prize for Literature in 1913. He was the first Bengali, first Indian and first Asian to win the award. That was the only unparalleled example during that time, but the contribution of the Tagore family is mammoth.

British Orientalism was another significant factor that worked to shape the Bengal Renaissance during the nineteenth century, particularly on religio-cultural matters. As much as English language education brought the ideas of West to India, so did the era of Orientalism facilitate spread of innovative cultural attitudes to the bhadraloka. British Orientalism was an inimitable phenomenon in British Indian history that was inspired by the requirements of the East India Company to tutor a class of British administrators in the languages and customs of India. Intellectually, this was one of the most powerful ideas of nineteenth century India.

In the political pre-independence scenario, a huge number of debating societies and newspapers appeared. Personalities like Kashi Prasad Ghosh (1809-1873), Kristo Pal and Sisir Kumar Ghosh explicitly expressed their political opinions and would not hesitate to exercise their newspapers to achieve political ends, often in direct defiance to British rule. Ultimately the roots of Indian independence can be traced back to the Bengal Renaissance.

Theatre of Bengal Renaissance

Bengal witnessed what was termed even in its own time as a "Renaissance" between 1795 and the last quarter of the nineteenth century. This is one period of Indian history that brought about the most radical changes the subcontinent had seen since the rise and fall of Islamic rule in India through various time periods. The Bengali Renaissance was the outgrowth of a grafting of British culture onto that of the more-than-willing native culture. This enormously enthusiastic response of the Bengalis to Western culture and its tenets imposed by the British was far greater than the adjustments required to cope with a colonial administration; it was a search for a cultural identity that could at some level set them at par with their European overlords; it was an attempt to beat their masters at their own game; it was a quest for an Indian cultural idiom that would more than cover the ignominy of being ruled and exploited by a foreign power.

It is in the wake of this endeavour to find or regain a respectful self-identity in the 1850s that several theatres were spawned in the native quarters of Kolkata. The new colonial socio-economic order had engendered a new society. The concentration of wealth in the hands of the babus and the rise of a Western-style educated middle class combined to give rise to the Bengali theatre. Babu wealth underwrote both leisure and arts patronage.

The growth of the middle class meant surplus creative energy seeking channels of expression. Close contact with the British, inspired both classes to create their own theatre in the European mould. With the coming of economic, political and social stability, with a mean being struck between the traditional Bengali culture and the British cultural imports, a system of patronage was born that was to keep Bengali theatre alive for some time.

It would be a site of pleasure limited to the elite babu circle. The modern Bengali theatre during 1840s was relatively quiet years as far as theatrical activities in the Bengali language were concerned. That does not mean that the Bengali elite were refraining from theatrical activities altogether. Their energies for this newly found Western-style of entertainment were channelled into producing plays not only in the style of their Anglo-Saxon masters but in their language too. In October 1844, under the active patronage of Babu Radhakanta Deb, two short plays in English were presented in a double bill: Lovers of Salamanca (author unknown) and The Fox and the Wolf (author unknown), directed by one Mr Barry, an Englishman.

A burgeoning new urban middle class was helping the cause tremendously, not simply by coming to see the plays but also by supplying a good number of actors. In 1854, Babu Pyari Mohan Basu founded his Jorasanko Natyashala (Theatre) where Julius Caesar was staged in English by a Bengali cast.

The problem apparently lay not in natives trying to play Shakespearean plays, but in playing him badly. But the problem could/would be resolved at once if the producers moved away from not only Shakespeare but also the English language. The burden of proof was not so much on the Bengali actor as on the Bengali language. It was a thinly veiled appeal to the community of Bengali babu to produce their plays in their own tongue.

Jayram Basak, another babu, took the appeal seriously and built a theatre in his house at Charakdanga, in the northern part of the city - Kolkata. It was here, in 1857, that the first noteworthy original play in Bengali was staged: the aforementioned Kulinkulasarbaswa by Tarkaratna. Two other plays, namely Kirtibilas and Bhadrarjun by J. C. Gupta and Taracharan Sikdar respectively, following Western tenets, had already been written (possibly in the 1830s). Although of doubtful artistic merit, these plays did not get staged probably for the lack of babu patronage. Kulinkulasarrbaswa, then, though not the first Western-style play to be written in Bengali, was the first to be seen on a Kolkata stage. A scathing social satire on the polygamous practice of the kulin group of Brahmans, it turned out to be a successful production with at least three performances in the course of three months. 1857 marks an important turning point in the history of Bengali theatre. It is interesting to note that from this year onwards, for coming few years, there was a burst of theatrical activity among the babus.

The Sepoy Mutiny in1857 was also an important year in the context of Indian history, and this got reflected in many of the plays that were staged. Perhaps, also, it was the active nationalist spirit of the Rebellion that indirectly shamed them into trying to reclaim a different kind of nationality through more passive cultural means. At least three new babu theatres had come into being in 1857. Ashutosh Deb`s Theatre (1857), the Bidyotsahini Theatre (1857) of Babu Kaliprasanna Sinha and the Belgachhia Theatre (1858) of Raja Pratapchandra Sinha all continued to produce Bengali versions of Sanskrit plays. Ramnarayan Tarkaratna himself returned to translating Sanskrit language plays with Bhattanarayana`s Benisangaham for Bidyotsahini Theatre. Kaliprasanna Sinha translated Kalidasa`s Vikramorvasi.