Emperor Aurangzeb as the last surviving proficient Mughal ruler, was much less involved in architectural production than his predecessors were; but he did sponsor imperative monuments, especially religious ones. Indeed, known to have turned much religious in nature during his old age, Aurangzeb and his architectural prowess and potential in Bengal, is quite rooted in building up of edifices religious in nature. Most notable of the spiritual instances are mosques that date prior to the court`s shift to the Deccan. Some of these, such as the Idgah in Mathura, were built by the ruler himself, others by his nobles to proclaim Mughal influence in the pressing times of opposition. On Aurangzeb`s palace mosque, one witnesses an elaboration of floral and other patterns, derived from those on Shah Jahan`s palace pavilions. But these forms are no longer intended to suggest the semi-divine character of ruler, a notion that little concerned Aurangzeb.

Emperor Aurangzeb as the last surviving proficient Mughal ruler, was much less involved in architectural production than his predecessors were; but he did sponsor imperative monuments, especially religious ones. Indeed, known to have turned much religious in nature during his old age, Aurangzeb and his architectural prowess and potential in Bengal, is quite rooted in building up of edifices religious in nature. Most notable of the spiritual instances are mosques that date prior to the court`s shift to the Deccan. Some of these, such as the Idgah in Mathura, were built by the ruler himself, others by his nobles to proclaim Mughal influence in the pressing times of opposition. On Aurangzeb`s palace mosque, one witnesses an elaboration of floral and other patterns, derived from those on Shah Jahan`s palace pavilions. But these forms are no longer intended to suggest the semi-divine character of ruler, a notion that little concerned Aurangzeb.

Early during Aurangzeb`s reign the harmonious balance of Shah Jahani-period architecture was thoroughly done away with in favour of an increased sense of spatial tension with vehemency on height. Stucco and other less high-priced materials emulating the marble and inlaid stone of earlier periods cover built surfaces, considered the most significant feature in architecture under Aurangzeb, which was also applied in Bengal, wholly divergent from his Mughal forefathers. Immediately after Aurangzeb`s accession, the use of forms and motifs such as the baluster column and the bangala canopy, earlier engaged for the ruler alone, are found on non-imperially sponsored monuments. This suggests both that there was relatively little imperial intervention in architectural patronage and that the vocabulary of imperial and divine symbolism established by Shah Jahan was undervalued by Aurangzeb. At the same time architectural activity by the nobility proliferated as never before, suggesting that they were eager to replete the role previously dominated by the emperor, an already repleted-role which is thoroughly witnessed in architecture of Bengal under Aurangzeb.

However, prior to establishing the solid consolidation of Aurangzeb`s Mughal architectural importance in Bengal, it is very much mandatory to comprehend the political set-up that had impressed upon the Mughal emperor and his builds. Although most of Bengal had been under Mughal rule since Jahangir`s time, Assam, Cooch Behar and Chittagong (all the three places serving absolutely under the then administered province of Bengal) lay outside the grasp of Mughal authority. Cooch Behar and Assam, territories to the north of Mughal Bengal, were conquered during the early 1660s. At that time temples were destroyed and mosques established, again for political purposes. Assam was eventually lost again, never to be consolidated into the Mughal Empire. To the southeast, however, Buzurg Umed Khan, the son of the empire`s leading noble, Shaista Khan, had conquered Chittagong, on the south-eastern coast of Bengal. The Mughals long had vied with local rajas and Portuguese adventurers for Chittagong. When Buzurg Umed Khan had secured it for the Mughals in 1666, it became a Mughal headquarters. In 1668, in Chittagong, he had completed a Jami mosque modelled on ones in Dhaka, although today it has undergone considerable change, commencing a dazzling era of Mughal architecture in Bengal by Aurangzeb, somewhat dissimilar from his erstwhile men.

For about twenty years, Rajmahal had been the capital of Bengal under the governorship of Prince Shah Shuja (one of the sons to Shah Jahan and brother to Aurangzeb). When Aurangzeb had assumed the throne, Shuja was pursued into the jungles of Assam where he had consequently expired. Aurangzeb`s governor then abandoned Rajmahal. One notable monument was constructed there, probably early during Aurangzeb`s reign. The tomb being referred to, is the tomb of Fateh Khan, a noble associated with Shah Shuja and his spiritual mentor Shah Nimat Allah. Fateh Khan`s rectangular tomb is surmounted by a deeply sloped bangala roof and appears to be the first extant instance in Bengal of a Mughal structure that is entirely covered with this roof type, commonly believed to have originated here. Thus such kind of Mughal architecture in Bengal under Aurangzeb was also not entirely free from vices, with brotherly political mayhem answering to the most of it.

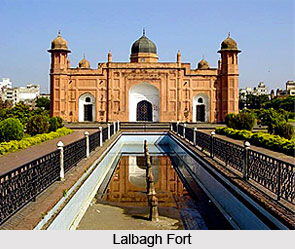

The capital Rajmahal was moved to Dhaka (a city which was during the then Mughal Bengal, absolutely under the administration and jurisdiction of India), which once again became the premier city of Bengal. Construction in Dhaka, long a major trade centre, had thus increased manifold. It was during this time that one of Dhaka`s most famous monuments, known today as the Lalbagh Fort, was built. Its construction is credited to Shaista Khan and Prince Azim al-Shan - Mughal governors of Bengal from 1678 to 1684. Within this compound, designed as a four-part garden, they had erected the tomb of Bibi Pari, an audience hall and an attached hammam, a tank, enclosure walls and gates. It thus comes as no surprise that architecture in Bengal during Auranzgeb was indeed grounded in religion and Islamic doctrinal aspects, which was chiselled upon the mosque or mausolea walls. Since the mosque within the Lalbagh Fort walls is dated to 1649, however, the present compound was probably built on the foundations of an earlier site. There is considerable empty space within the walls, and no residential quarters are apparent too. The structures in this Lalbagh Fort compound as well as their axial layout, adhere to the true imperial Mughal idiom. The appearance of the audience hall closely follows that of the Sangi Dalan in Rajmahal, as well as the viewing pavilion in the Agra Fort. Bibi Pari`s tomb is modelled on that of Shah Nimat Allah in Gaur, which in turn is inspired by the tomb of Itimad ud-Daula in Agra. However, the placement of Bibi Pari`s tomb adjacent to the audience hall is quite out of place, perhaps yet another architectural difference in Bengal under Aurangzeb, moved away from the earlier regal Mughals. Although the tomb reputedly contains the remains of Shaista Khan`s favourite daughter, Bibi Pari, that does not explain the unorthodox location of the tomb.

Despite the fact that the compound is almost universally addressed as the `Lalbagh Fort`, it more closely resembles an elaborate walled garden, for instance, the Arara Khass Bagh in Sirhind, though the Lalbagh is not terraced. No structure in the compound is inappropriate to a garden. As was the case with most imperial gardens, it appears originally to have been intended for ceremonial and administrative purposes, as well as for pleasure. In the life of a prince, these functions were not entirely discrete, which answers partly about the architecture of Bengal during Aurangzeb and his disjointed-ness in building elements.

Dhaka, like the other Mughal urban centres, possesses several surviving mosques belonging to Aurangzeb`s reign. Amongst them is the Satgumbad mosque, un-inscribed but traditionally credited to Shaista Khan. Others include the mosque of Hajji Khwaja Shahbaz built in 1678-79, the mosque of Kar Talab Khan (the future Murshid Quli Khan) constructed between 1700 and 1704, and the mosque of Khan Muhammad Mirza, dated 1704-05. All these are instances of being single-aisled, multi-bayed mosques surmounted by domes. Both their interior and exterior surfaces are significantly articulated. Architecture in Bengal under Aurangzeb absolutely had conformed to such an aspect, viewed in stray illustrations of tombs and mosques.

Burdwan was another city in Bengal long associated with the Mughals. Architecture in Bengal during Aurangzeb in places like Burdwan and its surrounds was nearly mostly accomplished as a contending issue between the father-son duo Shah Jahan-Aurangzeb. Although the mosque in Burdwan is not an outstanding structure, the tomb complex of Khwaja Anwar-i Shahid is the most refined monument in all Mughal Bengal, an architectural masterwork under Aurangzeb. This complex includes a splendid gateway, tank, mosque, madrasa and the tomb itself - all within a walled enclosure. Even though tradition states that the tomb complex was finished in 1712 by the future emperor Farrukh Siyar, also in Burdwan during the time of the ambush, it may have been the product of Azim al-Shan`s princely patronage. The three-bayed mosque`s highly articulated interior is replete with cusped niches. Such ornateness is unprecedented on any seventeenth- or early eighteenth-century Bengali mosque and is probably inspired by imperial architecture such as Aurangzeb`s Badshahi mosque in Lahore. Yet again, a striking and dissimilar instance is noticed in Bengal`s architecture under Aurangzeb. The interior of this Burdwan mosque probably served as a basis for later eighteenth-century architecture in Murshidabad. The tomb, however, is the most creative structure in the complex. Its format, unique in India, consists of a square single-domed central chamber with rectangular-plan wings on the east and west sides crowned by bangala roofs. The tomb`s plastered facade is covered with cusped medallions and niches as well as finely incised geometric patterns that call to mind the exterior of Sultan Nisar Begum`s tomb in Allahabad.

Terracotta temples were indeed constructed in Bengal in unprecedented numbers - thus bringing to light Aurangzeb`s architecture and plannings in Bengal. There are virtually forty dated terracotta temples and many others as well, all dated to the said emperor`s times; a variety of terracotta temple types were produced. The facades of most of these temples have been profusely embellished with images of deities and genre scenes, signalling the strength of the Hindu visual tradition.

The founding of Calcutta by Job Charnock in 1690 and its subsequent fortification, although of little significance during Aurangzeb`s reign, was ultimately to affect the future of the Mughal Empire and its successor states. For the next 150 years in Bengal, three rich building traditions - Mughal-type mosques, Hindu temples and British secular structures - made this eastern area the most diverse in all North India. An established path can thus be comprehended with regards to the termination of Mughal architecture in Bengal under the last able Mughal, Aurangzeb, with 19th century British patterns penetrating in to lend Bengal the most substantial place till Indian Independence.