Introduction

South Garo Hills District lies in the southern part of Meghalaya, and was created on 18th of June, 1992. This district of Meghalaya has its administrative headquarters at Baghmara, the only town in the district. Total population of South Garo Hills District as per Census 2001 is 1,00,980, out of which male population is around 51,000 and female population is nearly 48,100. Further, literacy rate according to 2001 Census is 55.82 percent, male literacy rate accounts for almost 62.60 percent and female literacy rate is around 48.61 percent.

South Garo Hills District lies in the southern part of Meghalaya, and was created on 18th of June, 1992. This district of Meghalaya has its administrative headquarters at Baghmara, the only town in the district. Total population of South Garo Hills District as per Census 2001 is 1,00,980, out of which male population is around 51,000 and female population is nearly 48,100. Further, literacy rate according to 2001 Census is 55.82 percent, male literacy rate accounts for almost 62.60 percent and female literacy rate is around 48.61 percent.

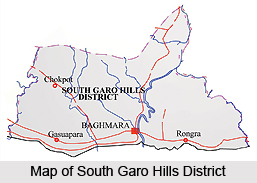

Location of South Garo Hills District

South Garo Hills District is situated between 25 degree 10 minutes and 25 degree 35 minutes north latitudes and 90 degree 15 minutes and 91 degree east longitude. This administrative district covers a total area of 1887 sq kms. It is bounded in the north by East Garo Hills District, in the east by West Khasi Hills District, in the west by West Garo Hills District and in the south by Bangladesh.

History of South Garo Hills District

History of South Garo Hills District is not very clear because of the complete absence of written or concrete records prior to the coming of the British rulers. The past history of South Garo Hills District is entirely based on the legends and oral traditions, folklore and folksongs, and other circumstantial evidences of its early inhabitants, Garo Tribe. According to their own traditions, the Garos came originally from Tibet and settled in Cooch Bihar District of West Bengal. From there, they moved to Guwahati and eventually into the hills. Another tradition ascribing some support to this theory, maintains that the Garos are descended from their forefathers in Asong Tibetgori.

History of South Garo Hills District is not very clear because of the complete absence of written or concrete records prior to the coming of the British rulers. The past history of South Garo Hills District is entirely based on the legends and oral traditions, folklore and folksongs, and other circumstantial evidences of its early inhabitants, Garo Tribe. According to their own traditions, the Garos came originally from Tibet and settled in Cooch Bihar District of West Bengal. From there, they moved to Guwahati and eventually into the hills. Another tradition ascribing some support to this theory, maintains that the Garos are descended from their forefathers in Asong Tibetgori.

During the Mediaeval period and the Mughal era, the more important estates bordering the Garo Hills were Karaibari, Kalimalupara, Mechpara and Habraghat in Rongpur district, Susang and Sherput in Mymensing district of Bengal and Bijini in the Eastern Duars. Early records describe the Garos as being in a state of intermittent conflict with Zamindars of these large estates. Further, medieval period history of South Garo Hills District also states that while the Garos in the hills were still divided into a number of minor Nokmaships, the plain tracts came to be included in the Zamindari Estates. Eventually these estates developed into fewer but larger complexes.

Besides, the early and medieval period, the history of South Garo Hills District also includes modern period. It states that the contact between the British and the Garos started towards the end of the 18th Century after the British East India Company had secured the Diwani of Bengal from the Mughal Emperors. Consequently, all the estates bordering Garo Hills, which for all practical purposes had been semi-independent, were brought under the control of the British rulers. Though political control had passed from the Mughals to the British, the latter, like Mughals, had no desire to control the Estates or their tributaries directly. The Zamindars were not disturbed in the internal management of their estates. Thus in the beginning, the intermittent conflict between the Zamindars and the Garos went on unabated until the situation deteriorated to the extent that the British were forced to take notice. This development led ultimately to the annexation of the Garo Hills in 1873 by the British. Captain Williamson was the first Deputy Commissioner of the unified district. The district was bifurcated into two districts - East Garo Hills District and West Garo Hills District in October 1979. West Garo Hills District was further divided into two administrative districts of West and South Garo Hills on June 1992.

Culture of South Garo Hills District

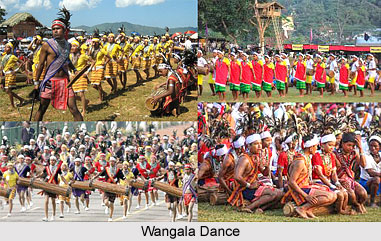

Culture of South Garo Hills District is of a tribal nature as the district is principally inhabited by the Garo Tribe. Culture of South Garo Hills District is characterized by several features associated with the Garos. Like for instance, their traditional political setup, social institutions, marriage systems, dialects, inheritance of properties, religion and beliefs. Songs, dances and music are an integral part of the traditional religious functions and ceremonies of the Garo people.

Culture of South Garo Hills District is of a tribal nature as the district is principally inhabited by the Garo Tribe. Culture of South Garo Hills District is characterized by several features associated with the Garos. Like for instance, their traditional political setup, social institutions, marriage systems, dialects, inheritance of properties, religion and beliefs. Songs, dances and music are an integral part of the traditional religious functions and ceremonies of the Garo people.

Garos have a matrilineal society where children adopt their mother`s clan. Interestingly, much of Garo religious practices relate to nature. In all religious ceremonies, sacrifices were essential for the propitiation of the spirits. Garo society is entirely casteless. Garo tribe is divided into five exogamous divisions called Chatchis (sometimes rendered as Katchis). Two of these are relatively unimportant in that they include an insubstantial part of the population. The important ones are the Chatchis named Marak, Momin and Sangma. The initiative in any move towards marriage is usually taken by the bride`s family, perhaps even by the girl herself. In the rural areas, people still prefer their old-fashioned houses which are comparatively easy and quick to erect.

The Garos normally do not use many ornaments. The common ones are strings of beads and earrings worn both by men and women. Both men and women prefer dark coloured clothes, either black or dark blue, and men wear shorts. Turbans are generally worn by them. There are no organized games as such among the Garos. However, games are generally played occasionally. Jumping contests and other competitions are conducted as tests of strength. The young males, members of the Nokpantes may organize themselves into groups and engage in such contests. Communal fishing activities are also organized. The common and regular festivities are, of course, those connected with agricultural operations. Greatest among Garo festivals is the Wangala which is more a celebration of thanksgiving after harvest. There is no fixed date for the celebration; this varying from village to village, but usually, Wangala is celebrated in October. Preparations take place well before the celebration date. Colourful Wangala dance adds charm to the entire celebration. In this dance both men and women take part.

People of South Garo Hills District

People of South Garo Hills District are inclusive of the numerous socio-cultural, political and economic aspect of the life of the people of South Garo Hills. Legend has it that the Garos originally inhabited a province of Tibet named Torua and left Tibet for some reason in the distant past under the leadership of the legendary Jappa-Jalimpa and Sukpa-Bongepa. They wandered in the Brahmaputra River valley at the site of present day Jogighopa in Assam and gradually moved up the Assam valley for centuries in search of a permanent home. In the process, they survived the ordeals of wars and persecutions at the hand of the kings ruling the valley.

People of South Garo Hills District are inclusive of the numerous socio-cultural, political and economic aspect of the life of the people of South Garo Hills. Legend has it that the Garos originally inhabited a province of Tibet named Torua and left Tibet for some reason in the distant past under the leadership of the legendary Jappa-Jalimpa and Sukpa-Bongepa. They wandered in the Brahmaputra River valley at the site of present day Jogighopa in Assam and gradually moved up the Assam valley for centuries in search of a permanent home. In the process, they survived the ordeals of wars and persecutions at the hand of the kings ruling the valley.

Tribes of South Garo Hills District

They then branched out into a number of sub-tribes, and the main body under the legendary leader, Along Noga, occupied Nokrek, the highest peak in Garo Hills. A`Chik is the general title used for the various groups of people after the division of the race. The title is used to denote different groups such as the Ambeng, Atong, Akawe (or Awe), Matchi, Chibok, Chisak Megam or Lyngngam, Ruga, Gara-Ganching who inhabit the greater portion of the present Garo Hills. But the name applies also to the groups of Garos scattered at the neighbouring places in Assam, Tripura, Nagaland and Mymensing in Bangladesh.

Though the main feature of their traditional political setup, social institutions, and marriage systems, inheritance of properties, religion and beliefs are common, it is observed that as these units were isolated from one another; they have developed their own separate patterns. They also speak different dialects. Also their traditional songs, dances, music differ from each other. The song, dances and music are mostly associated with traditional religious functions and ceremonies.

Society of South Garo Hills District

The Garos have a matrilineal society where children adopt their mother clan. The simplest pattern of Garo family consists of the husband, wife and children. The family increases with the marriage of the heiress, generally the youngest daughter. She is called Nokna and her husband Nokrom. The bulk of family property is bequeathed upon the heiress and other sisters receive fragments but are entitled to use plots of land for cultivation and other purposes. The other daughters go away with their husbands after their marriage to form a new and independent family. This aspect of family structure remains the same even in urban areas. The Garo household utensils are simple and limited. They consist mainly of cooking pots, large earthen vessels for brewing liquor, the pestle and the mortal with which paddy is husked. They also use bamboo baskets of different shapes and sizes. The Garos have their own weapons. One of the principal weapons is two-edge sword called Milam made of one piece of iron form hilt to point. There is a cross-bar between the hilt and the blade where attached a bunch of cow`s tail-hair. Other types of weapons are shields, Spear, Bows and Arrows, Axes, Daggers etc.

The important ones are the Chatchis named Marak, Momin and Sangma. Of these again, the Marak and the Sangma Chatchis have a wider membership; it has been estimated that more than half of all the Garos belong to one or the other. The earlier practice of Chatchi exogamy is to a large extent still strictly observed. The majority of Garos still hold that a member of a particular "Chatchi" should not marry a member of the same Chatchi. For example, most Sangmas would shrink from marrying older Sangmas. The practice may be crumbling to some extent in urban society. Marriage within a Chatchi subdivision, or ma`chong as it is called, is on the other hand, scrupulously avoided, such a marriage being tantamount to incest. This, to a Garo, is a serious breach of moral laws which will draw upon the guilty person`s divine punishment, like being killed by wild animals or struck by lightning. Although a modernized Manda Sangma may not shrink from marrying an A`gitok Sangma, he will not think of marrying another Manda Sangma. The several Chatchis are subdivided into a large number of ma `chongs. As far as is known, no one has attempted to list the names of all the ma`chongs.

The important ones are the Chatchis named Marak, Momin and Sangma. Of these again, the Marak and the Sangma Chatchis have a wider membership; it has been estimated that more than half of all the Garos belong to one or the other. The earlier practice of Chatchi exogamy is to a large extent still strictly observed. The majority of Garos still hold that a member of a particular "Chatchi" should not marry a member of the same Chatchi. For example, most Sangmas would shrink from marrying older Sangmas. The practice may be crumbling to some extent in urban society. Marriage within a Chatchi subdivision, or ma`chong as it is called, is on the other hand, scrupulously avoided, such a marriage being tantamount to incest. This, to a Garo, is a serious breach of moral laws which will draw upon the guilty person`s divine punishment, like being killed by wild animals or struck by lightning. Although a modernized Manda Sangma may not shrink from marrying an A`gitok Sangma, he will not think of marrying another Manda Sangma. The several Chatchis are subdivided into a large number of ma `chongs. As far as is known, no one has attempted to list the names of all the ma`chongs.

In the matrilineal society of the Garos, property passes from mother to daughter. Although the sons belong to the mother`s Ma`chong, they cannot inherit any portion of the maternal property. Indeed, males cannot in theory hold any property other than that acquired through their own exertions. Even this will pass on to their children through their children`s mother after they marry. Among the Garos any of the daughters, even the eldest, if there are many, may be chosen as the nokna, or heiress, having proved her fitness to occupy this privileged position by her dutifulness to her parents. In case there are no daughters, the family can adopt any other girl, usually one having the closest blood relationship to the adoptive mother, first preference being given to one of the "non-heir" daughters (a`gate) of the woman`s sisters, who are, of course, among the closest female relations a woman can have.

Inheritance of property among the Garos is generally linked with matrimonial relations, and although men may have no property to pass on, they have an important say in deciding to whom it should pass. As has been stated earlier, the broad divisions of Garo society, the chatchis, are traditionally exogamous. Although the restrictions are probably weakening, particularly among urban Garos or those living in cosmopolitan settings, one can say that the overwhelming majority of Garos still observe them. Even in sophisticated society, however, the harsher restrictions in regard to marriage within the same ma`chong are still scrupulously observed. Broadly speaking, one can say that a man who belongs to the Sangma Chatchi will look for a bride among the other chatchis like the Marak or the Momin and vice-versa.

Matrimonial System in South Garo Hills District

The initiative in any move towards marriage is usually taken by the bride`s family, perhaps even by the girl herself. When the girl is the heiress, the father, with an eye to the property she will inherit may as staled earlier, get his own sister`s son, that is, his own nephew, as her prospective bridegroom. Among the Songsareks or non- Christians , the practice of` bridegroom capture, particularly in rural areas, still goes on. A girl may express her interest in a young man and ask her male kinsmen to get him for her. This may involve an arduous chase, especially if the boy is not interested because, perhaps, he still cherishes the freedom of bachelor life, and the matter may not end with his capture and his being brought to her house. In the circumstances, the captured bridegroom will try to escape but generally after a few such attempts, he becomes reconciled to the idea of settling down.

In spite of the comparative freedom enjoyed by young people in Garo society, the standard of morality is generally high and evens those who may have been guilty of youthful indiscretions settle down to a stable married life. In the urban areas, the types of buildings are generally what are called the "Assam type", with plank floors, plastered walls, ceilings of cloth or matting and corrugated iron sheet roofs. Buildings of this type are of particular advantage in earthquake-prone regions like the Garo Hills, being able to stand up to a high degree of stress.

Festivals of South Garo Hills District

Festivals of South Garo Hills District portray the enthusiasm and zeal of the people of South Garo Hills and they include the Wangala dance and etc. There are no organized games as such among the Garos, though this does not imply that they have nothing to amuse themselves with. Games are generally played occasionally.

Jumping contests and other competitions are indulged in more as tests of strength. The young males, members of the Nokpantes or Bachelors` Dormitories, may organize themselves into groups and engage in such contests as the wa`pong sika, the Garo version of the tug-of-war, in which a stout bamboo pole replaces the rope and the contesting teams try push each other beyond a marked line instead of pulling. Again, the villages may turnout in strength to take part in communal fishing.

Jumping contests and other competitions are indulged in more as tests of strength. The young males, members of the Nokpantes or Bachelors` Dormitories, may organize themselves into groups and engage in such contests as the wa`pong sika, the Garo version of the tug-of-war, in which a stout bamboo pole replaces the rope and the contesting teams try push each other beyond a marked line instead of pulling. Again, the villages may turnout in strength to take part in communal fishing.

The common and regular festivities are, of course, those connected with agricultural operations. Greatest among Garo festivals is the Wangala which is more a celebration of thanksgiving after harvest in which "Saljong", the god who provides mankind with Nature`s bounties and ensures their prosperity, is honoured. There is no fixed date for the celebration; this varying from village to village, but usually, the Wangala is celebrated in October. Preparations take place well before the date; items of food are among the first to be collected. The Nokma of the village takes the responsibility to see that all arrangements are in order. Rituals in his house and in the individual fields precede the feasting at which guests are literally force-fed by the hosts. A large quantity of food and rice-beer must be prepared well ahead. The climax of the celebrations is the colourful Wangala dance in which men and women take part in their best clothes. Lines are formed by males and females separately and to the rhythmic beat of drums and gongs and blowing of horns by the males, both groups shuffle forward in parallel lines. Variety is added by the performance of a skilled dancer who ties a large fruit to the end of a string about half a meter in length and by a skilful manipulation of his body sets it swinging round and round behind him. This part of the dance usually wins enthusiastic applause.

Christian work inside Garo Hills having started about 1878 with the American Baptists who had, however, started their work among Garos in Goalpara since 1867. The Roman Catholics began their work in the plains areas first around 1931 -32, following it up with the establishment of a base at Tura (1933); since then it has extended to other parts of the Garo Hills. Between 1961 and 1971 the number of people returned as "Songsarek" underwent a decline and it would appear that their decrease has largely been due to the advance of Christianity. It can indeed be stated that the vast majority of Garos profess only these two beliefs that is, they are either Songsarek or Christian.

In earlier works on the Garos, as indeed on all the tribes of the North-East, the tenn Animism, was applied to the tribal faiths. This was perhaps oversimplification of a complex subject. It is true that much of Garo religious practices relate to Nature. They attribute the creation of the world to the Godhead, Tatara-Rabuga. Next in rank but more intimately concerned with human affairs is Saljong, who is the source of all gifts to mankind. He is honoured with the Wangala celebrations. Another benign deity is Chorabudi, the protector of crops. The first fruits of the fields are offered to him. He is also honoured with a pig sacrifice whenever sacrifices are offered to Tatara-Rabuga.

In earlier works on the Garos, as indeed on all the tribes of the North-East, the tenn Animism, was applied to the tribal faiths. This was perhaps oversimplification of a complex subject. It is true that much of Garo religious practices relate to Nature. They attribute the creation of the world to the Godhead, Tatara-Rabuga. Next in rank but more intimately concerned with human affairs is Saljong, who is the source of all gifts to mankind. He is honoured with the Wangala celebrations. Another benign deity is Chorabudi, the protector of crops. The first fruits of the fields are offered to him. He is also honoured with a pig sacrifice whenever sacrifices are offered to Tatara-Rabuga.

Living so close to Nature, the early Garo people the world around them with a multitude of spirits called mite, some of them good and some of them capable of harming human beings for any lapses they might commit. Appropriate sacrifices are offered to them as occasions demand. In all religious ceremonies, sacrifices were essential for the propitiation of the spirits. They had to be invoked for births, marriages, deaths, illness, besides for the good crops and welfare of the community and for protection from destructions and dangers.

Like the Hindus, the Garos used to show reverence to the ancestors by offering food to the departed souls and by erection of memorial stones. Like other religions, the Songsarek religion ascribes to every human being the possession of a spirit that remains with him throughout his lifetime and leaves the body at death. There appears to be a belief in reincarnation, people being reborn into a lower or higher form of life according to their conduct in their lifetime. The greatest blessing a Garo looks forward to is to be reborn as a human being in his or her original Ma`chong or family unit. Garo society is entirely casteless.

Geography of South Garo Hills District

Geography of South Garo Hills District is hilly with difficult terrains. The tropical vegetation covers areas up to an elevation of around 1000 metres.

The majority of the forests fall in this zone. It embraces evergreen, semi-evergreen and deciduous forests, bamboo thickets and grasslands including riparian forests and swamps. These forests mainly consist of Shorea robusta and in certain area Tectona grandis has also been introduced. The ground flora in deciduous forests is very poor and seasonal, while in evergreen forests, species of Alpinia, Amomum, Colocasia, Costus, Hedychium, etc. are not uncommon. Different varieties of beautiful birds are found in abundance in the forest areas of the district.

The majority of the forests fall in this zone. It embraces evergreen, semi-evergreen and deciduous forests, bamboo thickets and grasslands including riparian forests and swamps. These forests mainly consist of Shorea robusta and in certain area Tectona grandis has also been introduced. The ground flora in deciduous forests is very poor and seasonal, while in evergreen forests, species of Alpinia, Amomum, Colocasia, Costus, Hedychium, etc. are not uncommon. Different varieties of beautiful birds are found in abundance in the forest areas of the district.

Administration of South Garo Hills District

Administration of South Garo Hills District comprises four Community and Rural Development Blocks and these are Baghmara Development Block, Rongara Development Block, Chokpot Development Block and Gasuapara Development Block. Moreover, there are three Assembly Constituencies within South Garo Hills District. Administrative set-up of South Garo Hills District is headed by the Deputy Commissioner. He is assisted by other officers.

Tourism in South Garo Hills District

Tourism in South Garo Hills District offers visits to several places including sites of historical importance as well as sites associated with cultural traditions of the Garos. Tourism in South Garo Hills District is also popular for the charming scenic beauty of the region. This region of Meghalaya is well known for its abundance of wild life, flora and fauna. All these attract the travellers from all parts of the country.

Tourism in South Garo Hills District offers visits to several places including sites of historical importance as well as sites associated with cultural traditions of the Garos. Tourism in South Garo Hills District is also popular for the charming scenic beauty of the region. This region of Meghalaya is well known for its abundance of wild life, flora and fauna. All these attract the travellers from all parts of the country.

Some of the popular tourist attractions of South Garo Hills District are mentioned below -

Balpakram National Park: This national wild life park, about 45 kms from Baghmara, is also known as the abode of perpetual winds. An awe-inspiring mini-canyon separates the Garo Hills plateau from the Khasi-Hills plateau across the Sib-bari rivulet. Balpakram plateau and canyon abound in plants and herbs of immense medicinal value, is also the home of all sorts of wild animals including wild bison, wild cow and elephants. Balpakram National Park has many mysterious and unnatural phenomena that are worth exploring. This is a place of not only mythological importance but also the natural habitat of many rare and exotic animals and plant life. The best time to visit this park is from April to mid June. Balpakram is considered as a sacred place.

Rongsaljong Agal: On the South Garo and Khasi Hills border there is a very interesting rock tank that is 120 ft long and 90 ft wide. Water here remains perpetually clear and transparent and at the same level throughout the year.

Rongsaljong Agal: On the South Garo and Khasi Hills border there is a very interesting rock tank that is 120 ft long and 90 ft wide. Water here remains perpetually clear and transparent and at the same level throughout the year.

Rongsobok Rongkol: Further east to the northern side of Balpakram, there is a beautiful cave that contains shining pieces of rock.

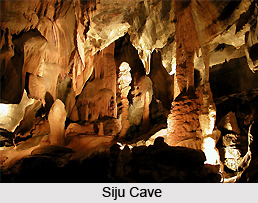

Siju Cave: The third longest cave in the Indian sub-continent, it is situated on the bank of the Simsang River just below the village of Siju. The cave is locally known as Dobakkol or the Cave of Bats. The cave consists of innumerable internal chambers and labyrinths which have not yet been fully explored. The cave is totally dark with a perennial stream flowing out of it, which abounds with different forms of aquatic life. Beautiful stalactites and stalagmites are found all over the cave. It is located 30 kms north of Baghmara. It is one of the longest caves in the Indian sub-continent and contains some of the finest river.

Siju Bird Sanctuary: Close by on the other side of Simsang River, Siju Bird Sanctuary is the home for many rare and protected birds. The migratory Siberian ducks also come here during the winter months.

Apart from the above mentioned sites there are many mysterious places at South Garo Hills District that are worth seeing. Tourism in South Garo Hills District means a memorable and enriching experience for those visiting this place. The nearest airport is Lokpriya Gopinath Bordoloi International Airport in Guwahati, which is around 350 kms from Baghmara.