Introduction

History of Indian Religion guides to the understanding of its religious beliefs and practices of various Indian Religions which have a large impact on the personal lives of most Indians and influence public life on a daily basis. Indian religions have deep historical roots that are recollected by contemporary Indians. India has a list of religious beliefs that represent Indian religion. The religious culture going back at least 4500 years has come down only in the form of religious texts. The religious beliefs postulated by human beings play a dominant part in the history of Indian religion and these beliefs are 100,000 years old.

History of Indian Religion guides to the understanding of its religious beliefs and practices of various Indian Religions which have a large impact on the personal lives of most Indians and influence public life on a daily basis. Indian religions have deep historical roots that are recollected by contemporary Indians. India has a list of religious beliefs that represent Indian religion. The religious culture going back at least 4500 years has come down only in the form of religious texts. The religious beliefs postulated by human beings play a dominant part in the history of Indian religion and these beliefs are 100,000 years old.

Role of Indian Religions on Indian Society

Religion is an integral aspect of life in India. The country is a secular state and respects all religion equally. History of Indian Religion is very ancient. India is the cradle of Hinduism, Buddhism, Jainism and Sikhism. The country also has followers of the religions such as Islam, Judaism, Christianity, Zoroastrianism and Baha"ism.

History of various Indian Religions

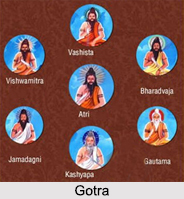

The recognised history of Indian Religion begins with historical Vedic religion. The religious practices of the early Indo-Aryans gave rise to certain religion. Their practices and rituals were collected and framed into the Samhitas. These texts are the central Shruti or revealed texts of Hinduism, which lasted from 1500 to 500 BC. Hinduism is a prehistoric religion and constitutes an overwhelming majority in the country. It is a ritualistic religion with various customs and traditions. The origin of this age-old religion is not documented and thus Hinduism can be called the native religion of the country.

After the 6th century BC, Jainism and Buddhism sprang up in India. Buddhism was founded by Gautama Buddha and was spread all throughout the country and beyond India through missionaries. Buddhism began in India as a reaction to the Vedic sacrificial system and the Brahmin`s control on religions. Jainism is another religion among the Indian Religions that was established by Mahavira. Besides Hinduism, Buddhism and Jainism are the oldest religions practiced today in the country. Sikhism was founded in the 15th century on the teachings of Guru Nanak in Northern India. Though Christianity and Islam originated outside the Indian subcontinent, yet with the frequent invasions these religions became popular in the country. Christianity arrived in India with apostles of St. Thomas. St. Francis Xavier was the person who helped in spreading Christian missionary activity in the country. He arrived in the country in the 16th century and worked in the fields of reform and education. Zoroastrianism originally arrived with the traders and was represented by small population and mostly settled down in and around the Indian West Coast.

The emergence of Islam in the country is simultaneous with the Turko-Muslim invasion of medieval India. Islam has made noteworthy religious, artistic, philosophical, cultural, social and political influences to Indian history. An in-depth study of the Indian religion helps to explore India. A review of the growth and the development of western civilizations included their language, literature, history and religion. History of Indian Religion also reveals the authentic form of Sanatan Dharma and tells the original philosophy of Vedas, Puranas, Bhagavad Gita, Bhagwatam and Darshan Shastras.

The distinctness of Indian religious system finds expression with the truth that in the diversity of beliefs, castes, rituals and religions India has given liberation to them and allowed each of them equal status.

Sacred Scriptures in Indian Religion

All religions have their own sacred scriptures. These scriptures are considered to be divine and holy in origin. The monotheist religions such as Islam, Christianity, etc. consider their sacred texts to be the word of their God.

Hinduism is a vast religion and has various texts that they view as sacred. The Vedas are very important religious scriptures. Amongst the Vedas, Rigveda is considered to be composed between 1300-1500 BCE and is considered to be world`s oldest scriptures. Bhagavad-Gita is considered to be the most important religious book.

Buddhism in due course established Universities at Nalanda, Vikramashila and Taxila in which many monks and chiefs studied. A large number of Buddhist literatures have cropped up as a result of these Universities. Many of these Buddhist writings are found in Tibetan texts, Chinese translations, and even in distant Northwest countries.

Christian Bible is compiled of various books written by followers of Jesus. These collections of books are also known as `New Testaments`. The Bible holds all teachings of Jesus on how all Christians should live out their lives.

The oldest Parsi scripture is known as Gatha. Because it was later written in Zend (Commentary) and Ayesta (the language it was written in), it came to be known as Zendavesta.

The Quran contains the spoken words of Allah. The Quran is revealed in Arabic language and is known for its inimitable excellent language. It has 114 chapters that are not chronologically arranged. The different pronouncements by the Prophet at different intervals were recorded and arranged in their present form by orders of Caliph Uthman (645-656). It is worthy of note that the prophet was not a man of letters. Therefore, the utterances in the Quran are considered to be genuine speech of God himself.

Kitab-i-Iqan was written partly in Persian and partly in Arabic by Bahá`u`lláh, the prophet founder of the Bahá`à Faith in 1862. At this time Bahá`u`lláh was living as an exile in Baghdad which at that time was a part of Ottoman Empire.

Influence of Renaissance on Indian Religion

Influence of Renaissance was apparent on the religious ideals and philosophy. Thus, it can be said that the overall impact of Indian renaissance does not only considers the matter of ideals in literature, and of the relationship between poetry and philosophy. Religion in India includes the degradations of sacerdotal and personal selfishness; articulating divergent activities like God realisation, analysis of human nature, thinking process, etc. Religion is an instinctive mode of Indian thought. It is the religious impulse that determined the character and extent of the Renaissance in India. Religion, in a subtler sense is the mainspring of the Tagore poetry and the Tagore paintings, and there were many in the country looking for a new Renaissance in religion itself.

The period of renaissance saw a huge impact on the religion of the country. It was commonly believed that prophecy is a dangerous occupation in a land of vast attainment and incalculable potentialities. In India, translations of works on the Tantra Shastra and religious works are placed among the precious things. There are reprehensible practices connected with Tantric observance; but its honesty compels the recognition of the fact that every practice is supposed to be encouraged by Tantra with a view to the attainment of occult powers or spiritual illumination with no other motive than self-gratification. Tantra, on the contrary, throws its circumference around the whole circle of human activity by linking every phase of conduct with religion. It includes worship with flesh-foods because it recognises that this is inherent in certain stages of human development, and because it believes that they are more certain to be transcended through being associated with the religious idea than through being left alone, or in an antagonistic relationship to religion.

It is the recognition of spiritual distinctions that marks the Tantra as a scripture that will appeal more and more to the future and exercise growing renascent influence. With the passage of time, science has passed inwards from the physical to the psychical, and it draws religion with it in due time, and leave those systems outside that have not a psychological basis to their faith and practice. The renaissance period popularised the practices based on knowledge of and relation with the relative world.

Influence of Muslim Rule on Indian Religion

The religious policy of the Sultans, the relationship between the King and the `Ulamas` or the ecclesiastical class, the non-official religious movements during the period and the tone of the current morality among the people had an influence on Indian religion. A Sultan was confined to reading of the Khutba for the Friday and `Id` prayers; the fixing of the extent and the limits of religious prohibitions; the collection of taxes for charitable purposes; the waging of wars in defence of the faith; the adjudication of disputes and suppression of innovations in religion. The Sultan further set apart funds religious and charitable purposes. The Sultanate was an essentially secular institution with no room within it for a dogmatic attitude towards religion and no scope for the established religion to usurp the authority of the civil functionaries who derived their power from the king.

The religious policy of the Sultans, the relationship between the King and the `Ulamas` or the ecclesiastical class, the non-official religious movements during the period and the tone of the current morality among the people had an influence on Indian religion. A Sultan was confined to reading of the Khutba for the Friday and `Id` prayers; the fixing of the extent and the limits of religious prohibitions; the collection of taxes for charitable purposes; the waging of wars in defence of the faith; the adjudication of disputes and suppression of innovations in religion. The Sultan further set apart funds religious and charitable purposes. The Sultanate was an essentially secular institution with no room within it for a dogmatic attitude towards religion and no scope for the established religion to usurp the authority of the civil functionaries who derived their power from the king.

The Sultans were identified with those in authority and were later invested with divine attributes and disobedience to them was to be regarded as sinful. Mughal King Akbar was both secular and religious head of the Indian Muslims. Towards the close of the Sultanate there is a more tolerant attitude towards the Hindus and this was especially true in the case of many kingdoms which arose in the provinces with the weakening of the central authority at Delhi.

The religious class consisted of the theologians, the ascetics, the Sayyids, the Pirs and their descendants. Officially the theologians or the `Ulama` counted most. They manned the judicial and religious offices in the state. They were becoming fanatical and often forgetful of the true tenets of their faith. It was Sultan Alauddin Khilji first who put a curb to their ambitions. They were to decide only on judicial questions and strictly religious problems. Mohammad Tughlaq completely secularised the state. Firoz was more lenient. The ecclesiastical class became a handmaid of the Sultan`s political policy and administration.

Among the non-official religious movements were the development of Sufism among the Muslims and the Bhakti movement among the Hindus. The period of individualistic missionary activity begins from the eleventh century onward. Of the earliest missionaries Shaykh Ismail, Abd Allah, Nur-ud-Din can be mentioned. From the thirteenth century their numbers increased and there were important missionaries like Khwajah Muin-ud-Din Chishti of Ajmer, Jalal-ud-Din of Sind, Sayyid Ahmad Kabir of the Punjab and later on others like Baha-ul-Haqq, Baba Farid-ud-Din and Ahmad Kabir. From the fourteenth century the missionaries spread into Western India and the Deccan.

Sufi ideas have been spread throughout India. They have modified some schools of Hindu mysticism which has affected Sufism in India. The Sufis have split up into a number of sects. Sufism is devotional, pietistic and a natural revolt against the cold formalism of a ritualistic religion. Sufism found a congenial home in India with its warm, mystical yearning after union and fellowship with God. Their faith may be thus summarised. God has given all his sons or servants the capacity for union with Him. The Sufis in India were not characterised by religious fanaticism. They adopted Indian rites and principles into their faith. They gave to the Bhakti movement various devotional exercises and charged it with their own experiences of mystic and divine love. The pain of separation was forcibly expressed and was a sign of intensity of love towards God. The separation between God and man was maintained in consonance with the principles of Islam.

As far as the moral life of the people was concerned it was marked by faith, love and piety. Loyalty and charity were appreciated and adhered to; courtesy and hospitality were enjoined upon and properly observed. The intense love of religion among the masses and the development of devotional sects like those of the Sufis were the redeeming feature of the society at that time. It may be emphasized that the developing spirit of tolerance in this age crystallised itself in the reign of Akbar.