About Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan, Hyder Ali"s elder son, succeeded to his father"s throne on 29 December 1782, at the age of 32. Tipu Sultan was born in November 1750 and was called the "Tiger of Mysore". Tipu Sultan was the first son of Hyder Ali and his second wife, Fatima or Fakhr-un-nissa. Tipu was named as Sultan Fateh Ali Khan Shahab or Tipu Saheb. Apart from being a brilliant ruler, Tipu was also a scholar, poet, soldier and a staunch Muslim.

Tipu Sultan, Hyder Ali"s elder son, succeeded to his father"s throne on 29 December 1782, at the age of 32. Tipu Sultan was born in November 1750 and was called the "Tiger of Mysore". Tipu Sultan was the first son of Hyder Ali and his second wife, Fatima or Fakhr-un-nissa. Tipu was named as Sultan Fateh Ali Khan Shahab or Tipu Saheb. Apart from being a brilliant ruler, Tipu was also a scholar, poet, soldier and a staunch Muslim.

After his enthronement, Tipu was immediately immersed in the struggle against the English, continuing the war that had begun under his father and in which he had already taken a vigorous part. Tipu occupied the throne at a time when Mysore was fighting the crucial Second Mysore War with the British. The war ended in 1784 when Tipu Sultan and the English signed the Treaty of Mangalore. As per the treaty, both sides agreed to return the territories and the prisoners captured during the war. A war with the Marathas and the Nizam soon followed (1785-87) ending with military successes but with rather disadvantageous terms of peace. This was apparently because of Tipu"s anxiety that these two powers should not combine with the English, whom he consistently regarded as his principal enemy.

From his accession Tipu treated himself as an independent sovereign, not needing any diploma of inferior office from the Mughal court at Delhi. He, thus, dropped the name and title of the Mughal emperor from his coins, and started using the title "Padshah" for himself from January 1786. Tipu could now claim parity with full-fledged sovereigns, like the Sultan of Turkey and the King of France, both of whom personally received his ambassadors in 1787 and 1788. While these embassies might not have resulted in any substantial material support for him, in respect of either military resources or commercial advantage, the diplomatic stature gained by him certainly reinforced his prestige at home.

Though the titles of "Padshah" or "Zill-i Ilahi" (Shadow of God) were used by the Mughal emperors, but Tipu gave to his sovereignty a colour of religious militancy, which was not at all present in the Mughal imperial polity of the eighteenth century. Tipu would not put his own name on the coins he minted; rather the coin legends invoke God as the all-powerful Sovereign, and bring in the name of Muhammad the Prophet, and of Hyder.

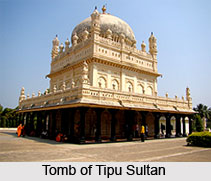

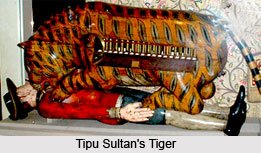

Tipu Sultan was a lover of art and culture. His palace at Srirangapatnam is known for its superb ornamentation. He minted a vast variety of coins from different mints. During his reign, French craftsmen worked in Mysore. One such artisan produced a wooden toy showing a tiger attacking a Britisher. The toy is now in the Victoria and Albert Museum, London. Like his father, Tipu too was buried at Srirangapatnam. Tipu Sultan was a tolerant ruler in the tradition of Islamic tolerance.

Tipu Sultan"s reforming zeal touched every department of life, including coinage and calendar, banking and finance, weights and measures, agriculture and industry, trade and commerce, morals and manners as well as social and cultural life. He built many strong forts such as the Doorg in Nilgiris to defend his kingdom. He had a quest for seeking knowledge. His personal library consisted of more than 2000 books in different languages. He had a dignified personality and impressed the people he came into contact with. He was an enlightened ruler who treated his non-Muslim subjects with tolerance generally. He conferred liberal grants to Singeri, Srirangapatnam and Mangalore temples.

The innovative ideas of Tipu Sultan enabled Mysore to gain importance even in the international spheres.

Tipu Sultan proceeded actively to rebuild the navy that Hyder had established. His major interest was in building ships which could be used for trade, though, being armed for defence, as was usual with merchant ships of the time, these could also be used in naval action. This embassy, really consisting of a board of four officers, had both diplomatic and commercial objectives. Moreover, Tipu was also looking beyond the Indian Ocean, and wished to open his own direct shipping line to Europe. In 1787, he proposed to send to France a ship with four hundred Indians aboard along with his embassy.

Apart from the constructive operations of Tipu also had to undergo several critical situations that took place due to his relation with the British. In 1783 Tipu directed the compilation, through Zainul Abidin Shustari, of a manual of mili¬tary organization and tactics, he significantly titled it Fathul Mujahidin, the Victory of Holy Warriors. This Holy War was to be directed against the English. In the instructions that he penned for his envoys to Constantinople he drew a picture of how the English had become a grave danger by their conquests and acquisitions. It is the English who, despite the dictates of Muslim theology to the contrary, were held to be infidels, the major enemy of Islam. All other enmities were secondary; all friendships were to be defined on this primary basis. His government, though strict and arbitrary, was the despotism of a politic and able sovereign, who nourishes, not oppresses the subjects who are to be the means of his future aggrandizement. His cruelties were, in general, inflicted only on those whom he considered as his enemies.

Tipu Sultan, Mysore"s last independent ruler, was distinctly an alternative element in late eighteenth-century South Asian political culture. Unlike the nominally independent Nizam Ali Khans, Asafuddaulahs, Nana Fadnavis or other princes and states¬men of an age when colonialism was destroying the Indian ancient regime brick by brick, Tipu, like his father Hyder Ali and his northern contemporary Mahadaji Sindhia, refused to be pliant and complaisant about British diplomatic blandishments allied with military threats during the age from Warren Hastings to Wellesley. Plebeian in his social origins, more of a ghazi than the average feudal carpet-knight, he was a throwback to the pre-Mughal Deccan Sultan, seeking accept¬ance of his imperial aspirations from West Asian and continental Euro¬pean peers, so as to effectively challenge British Indian competition for dominion in South India. More than any other indigenous ruler in eighteenth-century India, Tipu was interested in state power and its commercial capacity. But more than any of them, except his father and Mahadaji, he recognized the need to fight for it. He did this in a pragmatic way, using French absolutist alliance, Jacobian ideology, as well as the neo-Madari principles of a shaheed, without any scruples of artificial consistency, or ideological purity.

Tipu Sultan, Mysore"s last independent ruler, was distinctly an alternative element in late eighteenth-century South Asian political culture. Unlike the nominally independent Nizam Ali Khans, Asafuddaulahs, Nana Fadnavis or other princes and states¬men of an age when colonialism was destroying the Indian ancient regime brick by brick, Tipu, like his father Hyder Ali and his northern contemporary Mahadaji Sindhia, refused to be pliant and complaisant about British diplomatic blandishments allied with military threats during the age from Warren Hastings to Wellesley. Plebeian in his social origins, more of a ghazi than the average feudal carpet-knight, he was a throwback to the pre-Mughal Deccan Sultan, seeking accept¬ance of his imperial aspirations from West Asian and continental Euro¬pean peers, so as to effectively challenge British Indian competition for dominion in South India. More than any other indigenous ruler in eighteenth-century India, Tipu was interested in state power and its commercial capacity. But more than any of them, except his father and Mahadaji, he recognized the need to fight for it. He did this in a pragmatic way, using French absolutist alliance, Jacobian ideology, as well as the neo-Madari principles of a shaheed, without any scruples of artificial consistency, or ideological purity.

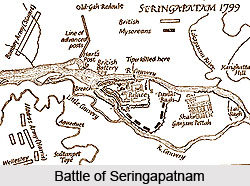

Due to the constant strife with the British resulted in the capturing Bangalore by the British. They finally defeated Tipu near Srirangapatnam (Seringapatam).The Third Mysore War ended with the Treaty of Srirangapatnam concluded between Mysore and the English in 1792. As per the treaty, Tipu was forced to surrender half his kingdom which the English, the Nizam and the Marathas divided this territory between themselves. Unlike many other natice Indian rulers, Tipu Sultan, consistently refused to accept the over lordship of the British. On the contrary, he wanted to chase the British out from India. For this, he tried to secure help from France. In fact, Tipu trained his soldiers with the help of the French. He also sent envoys to Afghanistan, Arabia and Turkey.

By now Wellesley succeeded Cornwallis as the Governor-general in India. Wellesley did not like the presence of French advisores in Tipu"s court. The English declared war on Tipu in 1799. General Harris and Arthur Wellesley (the brother of the Governor-general) attacked Mysore. A British force from Bombay also attacked Mysore. Tipu was defeated at Malavalli. He died on 4th May 1799. Later, most of Tipu"s dominions were shared by the English and their ally, the Nizam of Hyderabad. A small part of the Mysore kingdom was restored to Krishna, a member of the old Hindu royal family from whom Hyder Ali had captured the throne of Mysore.

Clearly, then, whatever Tipu wanted to do, he did not want to make war on the bulk of his own subjects. On the contrary, despite undoubted constraints, he was driven by a desire to improve the conditions of his people and thereby add to his own resources.

Administration of Tipu Sultan

Tipu Sultan, the great King of Mysore had enriched the administration of his state to a great extent by enacting some regulations in the economic, religious, military and foreign policies.

Tipu Sultan, the great King of Mysore had enriched the administration of his state to a great extent by enacting some regulations in the economic, religious, military and foreign policies.

Tipu Sultan was a devout Muslim but he had respect for other religions also and due to this reason he established several Hindu temples and mutts and maintained regular correspondence with them. Some of the historical evidences notify that Tipu Sultan

was personally involved with the Hindu religious places and helped them to establish temples. He also gifted the authorities of the temples with several articles like bells, silver cups etc for the use of the temples. Some of the deities were established and decorated as per his desire and he, in person was involved in the completion of the entire purpose. It has been said by the scholars that the involvement of Tipu Sultan in religious matters was the great influence he derived from his father Hyder Ali.

The mastery of Tipu Sultan was also seen in the sector of economic policies. Though agriculture was the main sector of the pre-modern eco¬nomy of Mysore, Tipu Sultan also tried to improve trade to support his territory with better economy. As his purpose was to bring the agricultural improvement, he took different measures to make agricultural development.

After Hyder Ali, Tipu took necessary steps in modifying the land tenure and restored what had existed in the lower Carnatic where Mughal influence had not penetrated deeply. Chiefly, he laid down certain rules for the distribution on arable land between the old and the new "rayats". There were four kinds of land, wet, dry, "hissa" and "ijra". "Hissa" lands were those where the produce was equally distributed between the state and the Peasant and he was not expected to pay any fixed tax like the "bhagra" lands in Bengal. "Ijra" land was that which was leased to the "rayat" at a fixed rent, like "theka" land in Bengal. Out of these four categories of land every peasant would have an equal share. The grain seeds sown in "ijra" land were greater in quantity than in "Hissa" land.

Tipu encouraged chiefly two varieties of land tenures, the institution of hereditary property and the fixed rent. The first may be described in technical language as "meeras", signifying inheritance. According to this the peasant secured the hereditary right of cultivation or the right of a tenant and his heirs to occupy a certain ground, so long as they continued to pay the customary rent of the district.

Tipu encouraged chiefly two varieties of land tenures, the institution of hereditary property and the fixed rent. The first may be described in technical language as "meeras", signifying inheritance. According to this the peasant secured the hereditary right of cultivation or the right of a tenant and his heirs to occupy a certain ground, so long as they continued to pay the customary rent of the district.

Apart from having an excellent economic and religious administration, Tipu Sultan possessed good military administration. He also possessed naval for¬ces. Tipu"s interest in the navy is evident from his letter to Ghulam Hussain dated 27 September 1786. The Mysore sovereign turned his thoughts seriously to building a navy after the defeat of 1792. A separate Board of Admiralty was established in September 1786 and express orders were issued for the building of 40 warships and a number of transport ships at the Jamalabad, Wajidabad and Majidabad dockyards and other places on the west coast. The army of Tipu Sultan was well constructed too. In the India Office Library there is a small but interesting manuscript containing the regulations for the encampment of Tipu Sultan"s army. It consists of seven tables preceded by a brief intro¬duction. There seems to be no doubt that it was drawn up not only for Tipu Sultan"s army, but under his guidance. The introduction lays special stress on the proper selection of that site for encampment of Tipu Sultan"s army. It stipulates that advantage should be taken, wherever possible, of rivers, streams, shrubs, rice-fields, hills, and thickets, which should be kept on one side and, after leaving an open space in the centre, soldiers should be encamped on the other side.

In addition to these policies, Tipu had made his mark in the foreign policies. To bring out the secular and liberal identity of his administration was the aim of Tipu. Being in very close relationship with France, Tipu was sure about the support and involvement in his political necessities. Moreover, Tipu had a desire to establish Islamic rule in the country and to make this work out he had to defeat the British. This was the reason why he solicited the assistance of Muslim countries namely Afghanistan, Persia and Turkey. Knowing the fact that the French were the rivals of the British, Tipu Sultan asked for the help of the French and maintained a good relationship with them for his benefit. Looking at the back and observing that the constant strife among the foreign powers for the struggle of supremacy had created a political turmoil in India, he decided to make an alliance with the French. Though the other foreign powers were defeated by the British, only the French survived and was in a powerful position. Thus it was difficult to defeat the French and due to this reason he made the presence of the French power visible in almost all sectors of his regime. He made his territory and power stronger by incorporating the French troop in his army, their influence at his court, and frequent visits of French adventures to his capital. It has also been said that the support of the French were observed since the reign of Tipu"s father Hyder Ali and this raised the hope in Tipu to stand against the British.

Religious Administration of Tipu Sultan

Religious administration of Tipu Sultan was one of the main practices he had accomplished. As per the history, Tipu tolerated the practice of Hindu religion within his own territory and became popular with all his subjects. Moreover, Tipu came to have a certain amount of faith in Hindus in the later part of his reign only as a result of his faith in the efficacy of Hindu ceremonies of incantation, etc.

Religious administration of Tipu Sultan was one of the main practices he had accomplished. As per the history, Tipu tolerated the practice of Hindu religion within his own territory and became popular with all his subjects. Moreover, Tipu came to have a certain amount of faith in Hindus in the later part of his reign only as a result of his faith in the efficacy of Hindu ceremonies of incantation, etc.

From the very beginning of his reigning period, Tipu Sultan was as sympathetic and faithful to the Hindus as to the Muslims. He made numerous charities and endowments to several Hindus and Hindu institutions. He granted several villages to the Hindus for building up Hindu temples, mutts, in the territory. He also granted permission for the construction of a mosque on the side of a Hindu temple. In addition to that, Tipu also granted life pension to some "acharyas" and to pagodas, presenting different articles for the temples and religious places. During the rule of Tipu, at the temples all the daily, annual and other periodical pujas, festivals, processions, worships, with all facilities and privileges provided for everyone connected with the temples according to traditions and all the court officials personally supported all the performances of the pujas. In Tipu"s time, the idol was installed in the Prasanna Venkateswara temple in Uratur in Kommaditima and provision was made for the expenses of daily worship and "inam" lands were granted to the Archakars and other servants of the temple.

Tipu Sultan was aware not only of the details of worship in Hindu temples, but, what is equally interesting is that he was aware of the delicate differences which have for generations together marked the Right-Hand and Left Hand sections of the people concerning privileges and honours in temples. Moreover, four different temples in four different parts of his kingdom received the privilege of royal gifts. These were the Ranganatha temple at the capital Srirangapattna, the Narasimha temple at Melukote, the Narayanasvami temple also at Melukote (Srirangapattna taluk), the Laksmikanta temple at Kalale (Nanjanagud taluk) and the Srikanthesvara temple at Nanjangud itself.The well-known Ranganatha temple at Srirangapattna was presented with seven silver cups and a silver camphor bearer by Tipu Sultan Pacca (Badshah), as is evident from the inscriptions on them.

But in all likelihood such gifts were not the outcome of fear on the part of Sultan Tipu. These bespeak a genuine desire on the part of that monarch to show marked favour to those temples in the welfare of which he may have taken some personal interest. There are two considerations which prove that Sultan Tipu was sincere in his motives when he made gifts to Hindu temples. First, the policy of making presents to temples had already been set by his illustrious father. Thus an inscription on a silver cup belonging to the Gopala-jysna temple at Devanahalli informs us that the silver vessel was a gift to the temple from Hyder Ali. Secondly, Sultan Tipu"s policy of giving gifts to Hindu temples was followed by his Muslim officials. That Sultan Tipu was not unaccustomed to look to the spiritual needs of his vast Hindu subjects is proved beyond doubt by the third and the most important consideration relating to his attitude towards the Hindu dharma. This concerns Sultan Tipu"s relations with the celebrated Hindu seat of learning, the Sringeri Matha, which form a very interesting chapter of Hindu-Muslim concord in the annals of India. But here it is worthwhile remarking that the tradition of maintaining the most cordial relations with the Hindu centres of spirituality had really been begun by Sultan Tipu"s wise father, Hyder Ali.

But in all likelihood such gifts were not the outcome of fear on the part of Sultan Tipu. These bespeak a genuine desire on the part of that monarch to show marked favour to those temples in the welfare of which he may have taken some personal interest. There are two considerations which prove that Sultan Tipu was sincere in his motives when he made gifts to Hindu temples. First, the policy of making presents to temples had already been set by his illustrious father. Thus an inscription on a silver cup belonging to the Gopala-jysna temple at Devanahalli informs us that the silver vessel was a gift to the temple from Hyder Ali. Secondly, Sultan Tipu"s policy of giving gifts to Hindu temples was followed by his Muslim officials. That Sultan Tipu was not unaccustomed to look to the spiritual needs of his vast Hindu subjects is proved beyond doubt by the third and the most important consideration relating to his attitude towards the Hindu dharma. This concerns Sultan Tipu"s relations with the celebrated Hindu seat of learning, the Sringeri Matha, which form a very interesting chapter of Hindu-Muslim concord in the annals of India. But here it is worthwhile remarking that the tradition of maintaining the most cordial relations with the Hindu centres of spirituality had really been begun by Sultan Tipu"s wise father, Hyder Ali.

From different historical evidences, it has been made clear that Sultan Tipu"s relations with the Hindu centre of spiritual learning were the influence of his father, Hyder Ali. From 1769 till 1780, Nawab Hyder Ali Khan Bahadur had made it clear that a new chapter had been opened by him in the history of the relations of the Muslim rulers of Mysore with the head of the Hindu seat of spirituality at Sringeri. A number of letters that were the evidences of the dealings of Tipu with religious heads of the temples and religious centres stand evidence for the fact that Tipu Sultan used to maintain a regular correspondence with the heads.

The numerous letters that are derived as historical evidences prove beyond doubt that Sultan Tipu was certainly a great benefactor of one of the most renowned places of Hindu worship. Moreover, he was prepared to place his country above his own self even in the matter of prayers. People have indeed reason to be grateful to him for the prompt measures he took to resuscitate the cause of Hindu dharma in the great seat of Shankaracharya, when it was eclipsed by political calamity.

Military Administration of Tipu sultan

The military administration of Tipu Sultan consisted of naval and army forces which were well developed by the Sultan considering almost all parts of militancy.

The military administration of Tipu Sultan consisted of naval and army forces which were well developed by the Sultan considering almost all parts of militancy.

To fight with the British forces Hyder Ali decided to form a powerful naval force and the same need was felt by Tipu Sultan and he took proper steps to reform the naval and army forces of Mysore and to curb the success of the East India Company. In doing so their strategy was to seek the help of the European rivals of the British namely the French, the Dutch and the Portuguese. They also succeeded in attracting some British subjects who helped them to build and also command some of their ships.

During the reigning period of Hyder Ali, a naval fleet was created some including good ports and ship building yards. Tipu possessed a number of men of war and had about 10,000 men staffing a variety of ships. He issued marine regulation in 1796 and ordered the immediate building of forty warships. Contemporary British records state clearly that Hyder Ali and later Tipu Sultan were most formidable enemies of the British. They maintained a steadfast alliance with the French against their common adversary. Evidence also exists of their efforts to maintain good rela¬tions with the Portuguese. The Mysore rulers had also tried to enter into alliances with Afghanistan, Muscat, and Turkey, which necessi¬tated the building of a strong navy. Moreover their English enemies were strong on the sea, their Portuguese neighbours relied on their navy in their struggle with Indian states, and the Peshwa possessed a fleet of his own. And the conquest of the Malabar Coast put Hyder Ali and Tipu in possession of the famous ports and the ship-building yards of that region.

Earlier, Hyder Ali built watercrafts in the East India Company"s marine yards at Honavar in 1763. He is reported to have had a large fleet which the East India Company claimed to have destroyed in the year 1768. The Portuguese evidence proves that by 1765 the Mysore navy possessed 30 vessels of war and a large number of transport ships which were commanded by an Englishman with some European officers. The Portuguese records further explain how Hyder Ali planned to build the most powerful fleet in Asia by building a stockade above the waterline in the Gulf of Batical in 1778. Unfortunately, in 1780 Admiral Edward Hughes dealt a fatal blow to this maritime power.

It has been known that Tipu"s navy had practical existence as early as 1787. After the defeat of 1792, the Mysore sovereign turned his thoughts seriously to building a navy. A separate Board of Admiralty was established in September 1786 and express orders were issued for the building of 40 warships and a number of transport ships at the Jamalabad, Wajidabad and Majidabad dockyards and other places on the west coast.

In the establishment of British rule in South Asia naval supremacy, no doubt, played a vital role. Those who resisted British aggression either did not fully appreciate the value of naval power or lack¬ed the determination and resources to build up a navy which could offer effective resistance to the British naval might. Of the indigenous rulers, Tipu Sultan was one of the few who recognized the importance of naval power. In 1768 the desertion of his naval commander, Stannet, caused the loss of many ships. Tipu Sultan, on succeeding his father, first turned his atten¬tion to the building up of his army; but even so, he possessed from the beginning a number of war vessels. The chief function of these ships was to protect merchant ships from piracy. Administratively they were placed under the Malik-al-Tujar or the Board of Trade. The Third Mysore War convinced Tipu Sultan of the necessity of a strong navy, and during the last few years of his life he showed great keenness in this connection. By 1794 the Sultan had decided upon the construction of 40 warships.

In 1796 Tipu Sultan issued a "hukmnamah" or ordinance which laid down the regulations for the naval building programme which he had undertaken. It is addressed to the "mirs yam" or lords of the Admiralty who were eleven in number. These "mirs" constituted the Board of Admiralty with their headquarters at Seringapatam. The Board was established in the Jafari month of the Mauludi year 1224, reckoned from the birth of the Holy Prophet, corresponding to September 1796. Next in rank to the "mirs yam" were the "mirs bahr" who were officers of the highest rank to serve on the seas. Two of these were assigned to each squadron of four ships; in modern terminology they may be termed admirals or commodores.

In 1796 Tipu Sultan issued a "hukmnamah" or ordinance which laid down the regulations for the naval building programme which he had undertaken. It is addressed to the "mirs yam" or lords of the Admiralty who were eleven in number. These "mirs" constituted the Board of Admiralty with their headquarters at Seringapatam. The Board was established in the Jafari month of the Mauludi year 1224, reckoned from the birth of the Holy Prophet, corresponding to September 1796. Next in rank to the "mirs yam" were the "mirs bahr" who were officers of the highest rank to serve on the seas. Two of these were assigned to each squadron of four ships; in modern terminology they may be termed admirals or commodores.

The programme contained in the "hukmnamah" visualized a naval force of forty ships which was to be placed under the care and superintendence of the "mirs yam" as soon as they were ready. They were, moreover, to be built with all possible dispatch. The names given to them all ended with the word "Bakhsh", e.g., Muhammad Bakhsh, Ali Bakhsh, Sultan Bakhsh, etc. signifying "bestowed by" or gift of Muhammad, Ali and the Sultan respectively.

The ships were divided into three "kachehris" or divisions, namely, the "kachehri" of Jamalabad or Mangalore, the "kachehri" of Wajidabad or Bascoraje and the "kachehri" of Majidabad or Sadasheogarh. The first of these "kachehris" was to consist of 12 ships and the last two of 14 ships each. With a view to expediting the completion of the project two "mirs yam" assisted by a mirza-i-dajtar (office superinten¬dent) and a mutasaddi (accountant) were appointed at Mangalore from whence they were to superintend the construction of the vessels intended for the Jamalabad division. Two other "mirs yam", together with a mirza-i-daftar and a mutasaddi each, were stationed at or near Mir Jan Creek for the purpose of directing the construction of vessels for the Wajidabad and Majidabad divisions.

The Admiralty Board was supplied with a model ship with a tiger figure head according to which all the watercrafts were to be built. The timber for the ships was to be procured from the state forests and then floated down various rivers to the respective dockyards. The number of officers for the fleet fixed in the "hukmnamah" was as follows: there were to be in all 11 "mirs yam", all stationed at the capital and 30 "mirs bahr", of whom twenty were stationed on ships, two assigned to each squadron; and ten were to remain at the capital for instruction. The salary of the "mirs yam" and such "mirs bahr" as attended the court was to be fixed according to their qualifications. The twenty "mirs bahr" serving on the ships were to receive a monthly salary of 150 imamis or rupees.

The land establishment of each "kachehri" was to consist of three office superintendents, three writers, twelve clerks (gumashtas), one judge (qazi), two proclaimers, (naqib), eleven attendants (hazirbashi), eleven literate scouts (sharbasharari), and one chamber¬lain (farrash) who had charge of camp equipment and carpets, one torch-bearer or link-boy (mashalchi) and one camel-driver (sarban).

Each ship of the line included some officers like four "sardars" (officers) denominated first, second, third and fourth, two "tipdars" and six "yuzdars", along with a number of sub¬ordinate officers. The first "Sardar" was to have overall command. The second "Sardar", with one "tipdar" and two "yuzdars" under him, was placed in charge of the guns and gunners, the powder magazine and every¬thing else appertaining to the guns as well as of the provisions. The third "sardar", with one "tipdar" and two "yuzdars" under him, was in charge of the marines and small arms. He was also to look after spare tools, implements and stores. The fourth "Sardar" was to have particular charge of the "khalasis" or sailors, and of the artificers belonging to the ship such as blacksmiths, carpenters, etc. He was expected to superin¬tend the cooking of the food and its distribution among the crew. The navigation of the ship was also entrusted to him. He was to look after the tools and implements in immediate use which had to be kept in a proper condition. Any damage caused to the ship during war was to receive his immediate attention. All the above officers were to be carefully selected and only persons of good parentage and some amount of education were to be employed.

The complement of each line-of-battle ship was fixed at 346 men. Thus all the twenty line-of-battle ships together were to have an establishment of 6,920. The establishment was divided into five main categories: the musketeers, the gunners, the seamen, the artificers and the officers. Each category was divided into several sub-categories. Among the musketeers were included "tipdars", "sharbasharans", "nafir-nawazes" (fifers), "shahnainawazes" (trumpeters), "yuzdars" (lieutenants), "sarkhils" (second lieutenants), "jamadars" (sergeants), and privates. The gunners similarly were categorized as "tipdars", "yuzdars", "sarkhils", "jamadars" and privates. The seamen included "jaqdars", "dafadars" and privates. The artificers consisted of smiths and carpenters with a head-smith and head-carpenter. Officers included not only the first, second, third and fourth "Sardars" but also the pilots, "darughas", physi¬cians and superintendents of offices. Details were given in the "hukmnamah" of the compensations to be paid to the different classes of men. Apart from the regular salary there was also the institution of a subsistence allowance.

The complement of each line-of-battle ship was fixed at 346 men. Thus all the twenty line-of-battle ships together were to have an establishment of 6,920. The establishment was divided into five main categories: the musketeers, the gunners, the seamen, the artificers and the officers. Each category was divided into several sub-categories. Among the musketeers were included "tipdars", "sharbasharans", "nafir-nawazes" (fifers), "shahnainawazes" (trumpeters), "yuzdars" (lieutenants), "sarkhils" (second lieutenants), "jamadars" (sergeants), and privates. The gunners similarly were categorized as "tipdars", "yuzdars", "sarkhils", "jamadars" and privates. The seamen included "jaqdars", "dafadars" and privates. The artificers consisted of smiths and carpenters with a head-smith and head-carpenter. Officers included not only the first, second, third and fourth "Sardars" but also the pilots, "darughas", physi¬cians and superintendents of offices. Details were given in the "hukmnamah" of the compensations to be paid to the different classes of men. Apart from the regular salary there was also the institution of a subsistence allowance.

Twelve small ships were on the occasion delivered to the "mirs yam". Of these ten were cargo-boats, five of them at Mangalore and five at Onore. The other two were called Asadullahis. All these smaller vessels were to be used for training the naval crew for the ships which were being built. With the same object it was directed that a kind of buoy should be anchored in some suitable place and a flag erected thereon, to serve as a mark for practicing with cannon. Instruction was to be imparted to the gunners with the greatest care.

The "hukmnamah" insisted that the timber used in the cons¬truction of ships should be seasoned and for this purpose the wood, after being felled and barked should be kept lying from one to two years. Only when, judged by the highest standards, it was perfectly seasoned, was it to be used. The men recruited for service with the navy were to be sworn in at Seringapatam in the presence of Tipu Sultan himself, and then sent to their respective destinations. The movements and warlike operations of ships were similarly placed under the directions of the "mirsyam" and "Asifs". Four "kothis" or business houses, called "factories" in those times, two at Muscat and two at Kutch, which had already been in existence when the "hukmnamah" was issued, were placed under the "mirs yam" for the purpose of protection. At each of these factories two "yazaks" (platoons of 12 men) of the regular troops were to be stationed. It may well be that the naval building programme of Tipu Sultan was one of the important reasons why the British precipitated a war with him so that his plan might be nipped in the bud.

The formation of army of Tipu is also a notable feature of his military administration. The army of Tipu Sultan specified that advantage should be taken, wherever possible, of rivers, shrubs, rice-fields, streams, hills, and thickets, which should be kept on one side and, after leaving an open space in the centre, soldiers should be encamped on the other side. In between the soldiers and the central court should be located the camp followers, goods and chattel. The tents were to be pitched in such a manner as to avoid the wind so that the army might not be troubled with wind and dust. After these general remarks the tables that follow give seven patterns of encampment. The first table contains a rectang¬ular plan of encampment with an entrance in front only. Guns are located at all four corners and at the entrance. Two tents in front and one on each of the three sides seem to be meant for officers. The central position is occupied by the "bargah-i-mualla", elsewhere mentioned as "bargah-i-khass" or Tipu Sultan" own tent which is surrounded on three sides by two rows of tents, one of the inner guard and the other of the outer guard. In front of the "bargah-i-mualla" is the secretarial office and a little further are two rows of tents for the ad¬vance guard at the foot of which are the stables.

Still further and exactly opposite the "bargah-i-mualla" is the "naqqar-khanah" or the place where the drums were beaten at stated intervals, and there are two rows of shops. To the right of the "naqqar-khanah" is the place for the chief standard. Finally all these are surrounded by the tents of the soldiery. The second table has a river bend as the base on one side and the soldiers" tents are pitched in a single row forming the diameter for the semi-circular bend.

The third table has many features in common with the first table, with the difference that there are four entrances instead of one, and guns are placed close to one another and not only on corners. Stables for camels and elephants are located at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla". In the fourth table the "bargah-i-mualla" is protected by only one row of guards which is located at a distance of forty yards The tents of the soldiery are in four groups, two in front and two at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla", the two sides on the right and left of it are not utilized for the purpose. The fifth table follows the pattern of the fourth except that the tents both in front and at the back are arranged in perpendicular rows and not horizontally. The sixth table visualizes encampment by the side of a river and the camp is arranged parallel to it, there being a single row of tents in front and another at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla". The main feature of the seventh and the last table is that the tents are arranged mainly in two rows on the right and left of the "bargah-i-khass".

The third table has many features in common with the first table, with the difference that there are four entrances instead of one, and guns are placed close to one another and not only on corners. Stables for camels and elephants are located at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla". In the fourth table the "bargah-i-mualla" is protected by only one row of guards which is located at a distance of forty yards The tents of the soldiery are in four groups, two in front and two at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla", the two sides on the right and left of it are not utilized for the purpose. The fifth table follows the pattern of the fourth except that the tents both in front and at the back are arranged in perpendicular rows and not horizontally. The sixth table visualizes encampment by the side of a river and the camp is arranged parallel to it, there being a single row of tents in front and another at the back of the "bargah-i-mualla". The main feature of the seventh and the last table is that the tents are arranged mainly in two rows on the right and left of the "bargah-i-khass".

The seven tables together throw interesting light on an important aspect of the organization of Tipu Sultan"s army. The constructive arrangements of Tipu Sultan"s military administration testify about the keen precautious mentality and intense knowledge about the both side of combativeness. The details available in the "Hukmnamas" evidences that no doubt that the Mysore navy would have been the most powerful fleet in Asia and would have compared favourably with the best fleet in existence anywhere in the world, but the sudden death of Tipu in 1799 brought a bolt from blue and the formation of navy was stopped in midway.

Economic Policy of Tipu Sultan

The economic policy of Tipu Sultan was made in a very organized manner and he took initiative to develop the trading relation with some other countries also.

The economic policy of Tipu Sultan was made in a very organized manner and he took initiative to develop the trading relation with some other countries also.

Since agriculture was the main sector of the pre-modern eco¬nomy of Mysore, Tipu"s major concern was naturally with agricultural improvement. An order issued by Tipu shows concern that if revenue was collected at the wrong time, this would pauperize peasants by compelling them to sell their cattle. Such untimely collections were to be avoided, and "the resource-less" peasants were to be given "taccavi" loans "in the form of cattle and grain" in order to enable them to undertake cultivation. Old canals and embankments were to be repaired, and new ones built. Similarly, old dams thrown across rivers were to be repaired, and new ones constructed.

Tipu Sultan made some regulations which were largely in conformity with the traditional principles of earlier regimes including the Mughal administration. Tipu was also interested in furthering agricultural manufac¬tures. This is shown by a very interesting order he issued for raw-sugar manufacturers to be summoned and trained in the making of candied sugar and white sugar so that they might manufacture and sell these finer varieties in their own localities. Another indication of Tipu"s farsighted innovation was the introduction of sericulture in Mysore, which was to grow later into such a successful industry. The raising of mulberry trees was assigned to particular land-farmers (talluqdars). Twenty-one centres (kar-khanas) for the culture of silkworms were established; the worms were to be produced on a monthly basis and the amount achieved from it was paid into the treasury. Tipu looked forward to an increase in silk production year after year.

Such interest in agricultural improvement could be creditable enough. But it was in the sphere of manufactures that his endeavours especially distinguished him from all contemporary Indian potentates. In 1787, Tipu instruc¬ted his prospective ambassadors to France to tell the French king that he had in Mysore "ten workshops (karkhanas) where countless muskets (banadiq) were being manufactured".

The chief merchants in charge, of the factories of the Sultan"s Govern¬ment were appointed to the post of Chief merchants. They were to take care of the business of the ships and factories and the victorious army of the "Sarkar-i Khudadad" in the territories of other countries; to buy, sell and obtain coin and bullion, i.e. gold, silver, etc. and different kinds of cloth, sandal-wood, round pepper, small and big cardamoms, betel-nut, coconut, copra, rice, red sulphur and elephants and other commercial goods; to issue firm and true convenants to get invited and invite merchants from foreign countries; to select trustworthy accountants and alert, experienced, unselfish and honest agents (gumashta), who are skilled in accountancy and business, and appoint them over the factories; to look after the management of commercial business without any loss; to maintain accurate records and accounts, while at sea and in port; not to allow any theft or embezzlement; and not to show negligence in managing the entire affairs of the factories (kothis) and ships within the kingdom and outside. Considering God and his Prophet (Peace be on him) to be present as witness it is their duty of work for carrying out these duties in accordance with the Hukmnama within their own jurisdiction and other factories to the best of their ability. They should unite with one heart and one mind in conducting and effecting the business of the "Sarkar-i Khudadad". In the execution of business all officials should sit together and consult among themselves and without informing the mutasaddi, etc. they should record the statements of each person in their register, and obtain their signatures and put them in a box, setting a seal on the cover.

One of the most important aspects of Tipu"s life was his minting coins. Being an independent sovereign, Tipu after his succession over the throne, dropped the name and title of the Mughal emperor from his coins, and started using the title Padshah for himself from January 1786. Though the titles of Padshah or Zill-i Ilahi (Shadow of God) were those in use by the Mughal emperors, Tipu established his own individuality by incorporating his sovereignty a colour of religious militancy, which was not at all present in the Mughal imperial polity of the eighteenth century. Tipu would not put his own name on the coins he minted; rather the coin legends invoke God as the all-powerful Sovereign, and bring in the name of Muhammad the Prophet, and of Hyder i.e. Ali, the Prophet"s cousin and the model for heroes in Islam. His double-rupee was called "Hyderi", after Ali, and the single rupee was termed as "Imami", recalling the twelve "Imams" whose line begins with Ali. There is little doubt that the motif of tiger, so much emphasized in Tipu"s ceremonial symbolism, was designed to link him with the same hero of Islam whose title "Hyder" also meant a lion or tiger.

Tipu Sultan had also taken various measures to improve their transaction with the other countries through ships and foreign trades. By regulating the rules he had made the economic policy of his state to flourish.

Land Revenue system of Tipu Sultan

The land revenue system of Tipu Sultan was an excellent renovation that evidences his mastery over his administrative knowledge. After Hyder Ali, the task of completely developing the management of revenue fell to Tipu, who had acquired great knowledge and experience by his administration of the "jagirs" in Dharmpuri for fifteen years where he had introduced a number of reforms.

The land revenue system of Tipu Sultan was an excellent renovation that evidences his mastery over his administrative knowledge. After Hyder Ali, the task of completely developing the management of revenue fell to Tipu, who had acquired great knowledge and experience by his administration of the "jagirs" in Dharmpuri for fifteen years where he had introduced a number of reforms.

On his accession, Tipu Sultan modified the land tenure and restored what had existed in the lower Carnatic where Mughal influence had not penetrated deeply. Chiefly, he laid down certain rules for the distribution on arable land between the old and the new "rayats". There were four kinds of land namely wet, dry, "hissa" and "ijra". "Hissa" lands were those where the produce was equally distributed between the state and the peasant and he was not expected to pay any fixed tax like the "bhagra" lands in West Bengal. "Ijra" land was that which was leased to the "rayat" at a fixed rent, like "theka" land in West Bengal. Out of these four categories of land every peasant would have an equal share. The grain seeds sown in "ijra" land were greater in quantity than in Hissa land.

Tipu Sultan encouraged chiefly two varieties of land tenures, the institution of hereditary property and the fixed rent. The first can be described as "meeras" in technical language, suggestive of inheritance. According to this, the peasant secured the hereditary right of cultivation or the right of a tenant and his heirs to occupy a certain ground, so long as they continued to pay the customary rent of the district. The rent was paid only when the land was cultivated. But the state insisted on the cultivation of the land and that it should not be left fallow on any account. Those who defied this order ran the risk of forfeiting the land which was then bestowed on another. The rent varied under this tenure according to the produce. In the other tenure, system owner¬ship of the land was vested with a landlord who collected the rent from his tenants and paid a fixed rent to the state. After the death of the landlord, the land was passed on to his son, thus respecting the right of succession. Such a system existed in Bednore, Ballam, Mysore and Tayoor provinces. In Canara, all the lands which the landlords did not immediately manage themselves paid a fixed rent in money or kind. The farmers held the land directly from the government in Baramahal and there were no landlords in that province.

Tipu Sultan while managing his land revenue system introduced the system of collecting the rent in cash. As per this revenue system, the rents were fixed according to the grain and the lands were meas¬ured every year. If coins in metals like gold and silver, copper or brass were offered, they were accepted at their current prices in the bazaar. Farming out the land was abolished and the state undertook the task of collecting the tax directly from the peasants. State officers were strictly instructed not to harass the ryots (peasants or cultivators of the soil). They were not to interfere in their daily affairs except at the time of collecting taxes when they should adopt peaceful meth¬ods of collection. The rents fixed by the state were fair and moderate.

According to the land revenue of Tipu Sultan, those who cultivated dry land were assessed at about one-third of the crop. For the wet or rice lands, the payment was more, nearly half the crop and the tax was received in kind. The mode of esti¬mating the quantity of land was not by actual measurement but by the quantity of seed grains required to sow the arable land. The term used was "candy" which differed from district to district and from grain to grain. A candy of land meant the extent of land in which a candy of seed grain was sown. A candy consisted of twenty "kudus" and each "kudu" was of ten seers. There were varying types of "kudus". But to assure an equal share the produce was distributed half and half between the state and the farmer. The candy of dry land was almost four times larger than the candy of wet land which was considered much superior to, and hence charged at a higher rate than dry land. During the reign of Tipu, a particular measurement was followed in case of the rent of dry and wet land. The actual differences in rent between wet and dry lands was not 2-3 but 1-6 because the extent of one candy of paddy land was 24 measures, the state"s share was 12. For dry land it should have been 8 but actually the state took only 2 measures from dry land for the same area as that of wet land, as the gross yield was only 6 measures. Brahmin cultivators paid only half the usual rent as their womenfolk did not work in the field. The state dues were not very high compared to the rentals in the same period in England, where the peasant paid one-third to the landlord, one-third going as husbandry charges, with only one-third left to him. In Mysore, the state took one-third from the peasant leaving two-thirds to him.

The land revenue of Tipu Sultan was very well planned and well constructed. As per the norms of this system, lands were graded into three categories according to the fertility of the soil and the assessment depended on the productivity of the soil. A farmer cultivated both dry and wet lands and on an average he paid 40 per cent of his income to the state. The cultivation of a dry crop was most extensive and most certain. It was sown in the beginning of June and reaped in January. Nearly 25 varieties of crops were harves¬ted, the principal dry grains being ragi, jari, bajra, dhal, horsegram, Bengal gram and green gram. Rice and sugarcane were the chief wet crops grown near the reservoirs or with Kaveri water. There was even scope for second crop in the lands fed by this river but Tipu discour¬aged more than one crop as it would reduce the fertility of the soil. Besides these food grains, other commercial crops like areca-nut, pepper, cardamom, tobacco and sandalwood brought good revenue, which was collected on the basis of a fixed money rent. Repairs to the tanks were attended to with special care and urgency. These tanks stood in constant need of repairs owing to the heavy rainfall which brought down good quantities of earth, and washed away the embank¬ments in the rainy season. Cultivation of wasteland was encouraged by making it tax-free in the first year, charging one quarter in the second year, and the full thereafter. This was made possible by Tipu Sultan by his reforms for tax collectors to rob the ryots and the government as in the days of Hyder Ali.

The land revenue system of Tipu Sultan was a well planned system that was introduced by the king of Mysore to benefit and manage his territorial domains.

Foreign Policy of Tipu Sultan

The introduction of new political development in India led to the gradual fading of the traditional balance of power and this needed restoration of balance. The foreign policy of Tipu Sultan was centered upon these facts that had been troubling the national identity of India.

The introduction of new political development in India led to the gradual fading of the traditional balance of power and this needed restoration of balance. The foreign policy of Tipu Sultan was centered upon these facts that had been troubling the national identity of India.

The great king of Mysore was the sole personality who understood the real intentions of the British behind reducing the Rajas to the status of pensioned Nawabs. After failing to secure the support from Nizam and Marathas, Tipu Sultan planned to make alliance with Turkey, Afganistan, France and Iran. Behind the foreign policy of Tipu Sultan, there were two major purposes viz. to eliminate the British from the Indian power with the help of foreign power including political and military support from them. Another purpose was to make the economic betterment of the country and establish economic contacts with those countries. Another major aim behind making a strong bond with foreign countries was to curb the power of the British in the political, social and commercial sections of Indian life. Being one of the sources of precious commercial commodities, Mysore remained a place of great commercial importance. To improve the commerce and trade of Mysore and as a whole of India, Tipu also developed commercial relation with Pegu, Muscat, Ottoman Empire, Jeddah, Basra, Armenia, Ormuz and China.

Turkey being one of the major foreign forces was included in the foreign allies of Tipu Sultan. By sending ambassador to Constantinople in 1784 Tipu received favourable response from them. With the aim of terminating a political and military treaty against the English, Tipu in 1785, conserved an expanded embassy of four persons. The treaty between Mysore and Turkey had five clauses. The clauses specified that Turkey was to provide help to assist Tipu in the making of gun and cannon, another mentioned about the trading systems in Basra for acquiring similar trade benefits in Mysore. It has also been mentioned that the decline in the east was fastened by the negligence of commerce and industry.

In spite of the fact that the emissaries were treated with courtesy in Constantinople, but the major matter of the treaty was circumvented. Russia, at this point of time, was preparing to attack Turkey. Under such circumstances the Turks were in no mood to enrage the British by supporting India. As a result the Indian ambassadors had to return disappointed.

The foreign policy of Tipu Sultan specifies his relationship with the French from whom he received maximum support during any threat. Aware of the fact that the British were planning to establish their empire in India and affecting harmony among the princes, Tipu made an alliance with the French to curb the power of the British. The French being the early rivals of the British, developed hostile relationship and with the time, the resentment towards each other increased. This did not end till 1914, the year of the First World War. Due to the animosity that developed between the French and the British, Tipu took the advantage to make an alliance with the French and provoke the Europeans to take up war against each other. Though the constant threat of the British was still existent, Tipu"s alliance with the French and their overall presence in almost all segments of Tipu"s administration with sheer hatred against the British, assured him about the reoccurrence of the days of American independence in India.

Apart from being close alliance with the French, Tipu had developed union with Afghanistan. Before coming in contact with the ruler of Afghanistan Zaman Shah, Tipu had a negotiation with Kabul to seek military support to stand against the British. After arrival of Zaman Shah in India in 1799, the British directed an action on his western boundary. The British made it possible by provoking the Persians to attack Afghanistan in his absence. Later by sending off the Shia from Moradabad to Iran, Lord Wellesley successfully obviated the impending danger.

In addition to that, Tipu had a good relationship with Iran. With the aim of forming good commercial relations with Iran, Tipu had also wished to restart the old trade routes via Iran to Europe. He also intended to set up commercial centres in Iran which would provide same trade benefits to the Persians dwelling in Mysore. Though Tipu was trying to grab the impression of the Shah of Iran for the betterment of political and commercial contacts, Tipu"s fabricated plans were once again demolished by the British with the device of Shia-Sunni differences. Due to the superior diplomacy of the British, Tipu failed to form international contacts for his political and military purposes. Out-break of French Revolution may be cited as another reason of his failure.

Under these circumstances, Tipu Sultan failed to secure the support of French, Afghanistan or Turkey. Barred by several hindrances, Tipu"s plans remained unsuccessful and with time they ushered British dominance in India.

Tipu Sultan’s Confederacy

Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore took an attempt to sign treaties and made alliance with some powers, following the tradition of his father Hyder Ali. In 1779, Haidar Ali of Mysore built up a "terrible confederacy" with the help of the Nizam and all the Maratha chieftains, except the Gaekwar of Baroda, to destroy British power in India, a calamity that was averted by the Treaty of Salbai (May 1782) and the Treaty of Mangalore, with Hyder"s son, Tipu Sultan, in March 1784.

Tipu Sultan, the king of Mysore took an attempt to sign treaties and made alliance with some powers, following the tradition of his father Hyder Ali. In 1779, Haidar Ali of Mysore built up a "terrible confederacy" with the help of the Nizam and all the Maratha chieftains, except the Gaekwar of Baroda, to destroy British power in India, a calamity that was averted by the Treaty of Salbai (May 1782) and the Treaty of Mangalore, with Hyder"s son, Tipu Sultan, in March 1784.

That treaty was never accepted as final by Tipu Sultan who was even more ambitious than his father and lacked the chastening influ¬ence of misfortune. During his reigning period, Tipu solicited mandatory letters calling upon the Nizam and other Muslim chiefs of the Deccan to join him in the Holy War. But Nizam Ali Khan, the Subedar of the Deccan, was reluctant to listen to these calls for a confederacy. He was disposed to ally himself with the Marathas in another campaign against Mysore, to keep the unruly upstart from crossing the Tungabhadra. He sent an army, late in 1785, under Mushir-ul-Mulk, Mughal Ali and Sham Sher Jang to cooperate with the Marathas in the defence of Badami, Adoni, Nirgund and other forts.

The Guntoor Circar affair, long a thorn in the side of the Nizam, also became more alarming during this time. The territory was of great importance to him as the only outlet to the sea; it was equally valuable to the English, who had acquired a contingent right over it by the Treaty of 1768, because it lay between Madras and the Northern Circars. The Nizam was striving his utmost to retain the Circars.

It is significant also that the embassies from Hyderabad were ostensibly from Imtiaz-ud-daulah. The reason being one of the articles of the treaty by which an offensive and defensive alliance was formed, stipu¬lated that the daughter of the Nizam"s sister (married to Imtiaz-ud-daulah) should be given in marriage to Tipu Sultan. According to Colonel Read, for about two years there were constant rumours of the matrimonial alliance, as the basis of a political confederacy.

It is significant also that the embassies from Hyderabad were ostensibly from Imtiaz-ud-daulah. The reason being one of the articles of the treaty by which an offensive and defensive alliance was formed, stipu¬lated that the daughter of the Nizam"s sister (married to Imtiaz-ud-daulah) should be given in marriage to Tipu Sultan. According to Colonel Read, for about two years there were constant rumours of the matrimonial alliance, as the basis of a political confederacy.

Meanwhile, discussions proceeded rapidly and it was agreed that Tipu was to restore to the Nizam all the territory in his possession that pertained to the Deccan in the time of Nizam-ul-Mulk. Tipu also expressed a desire to include the Marathas in the alliance, and the Nizam himself was found by Colonel Read sending Sooraji Pandit, the Poona Vakil at Hyderabad, with a letter to Nana Fadnavis "to prevail on the Pant Pradhan to enter into a conference with His Highness, Tipu Sultan and the French against the English".

Tipu, therefore, ordered the Maratha Vakils and Hafiz Fariduddin Khan to attend him at Coonattoor and, about the middle of September 1789, Colonel Read was able to report that the basis of the negotiations.

The negotiations include:

•A firm and lasting union between Nizam Ali Khan and Tipu Sultan in all matters in which they mutually engage for the good of their two States.

•His Highness to join Tipu in a war against Marathas, at any time that nation shall oppose their views.

•The Guntoor Circar to be made over to Tipu for the usual rent and His Highness to break all connection with the English.

•His Highness to give his daughter to Tipu"s son in marriage.

Besides this, a truce was agreed upon with the Marathas for a period of three years and six months. As per history, Shivaji Rao, the Maratha Vakil, was in Tipu"s camp and that it was currently reported that the Marathas had entered into engagements to assist Tipu in the event of war with the English. This engagement was further corroborated by the discovery by Colonel Read of the following events, (mentioned in his despatch dated 4 January 1790).

Tipu"s Vakils at Hyderabad were given a rather cold audience on 2 January 1790, and they were sent back in April of that year, without any apparent mark of friendship from the Nizam. They also carried with them a definite refusal. Meanwhile, by his attack on Travancore, Tipu had invited the wrath of the Company on his head and Lord Cornwallis had, by conci¬liation and compromise, gathered together once again the broken threads of diplomacy. On 5 July 1790, a treaty of offensive and defen¬sive alliance was concluded between the Company, the Marathas and the Nizam. This aroused the wrath of Tipu and the walls of Daria Daulat Bagh Mansion reflect the pathetic perpetuation of Tipu"s wrath, at the break-up of his projected Confederacy.