Bengal had forever served a pivotal place and role since prehistoric Indian history. After the culmination of the ancient era in India the medieval period and the arrival of Muslims into India from Persia was ushered in. Thus was triggered in the era of Islamic India in which the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughals, and later the Nizams or Nawabs had tremendously tried to consolidate Bengal from the far-off eastern Indian counterparts. After the departure of the Mughals, the nizams and nawabs had taken over from the indiscriminately arising `princely states`, which had given rise to an entirely different form of architecture. Indeed, Murshidabad, the once tremendous and historic stronghold in Bengal, had given birth to an entirely dissimilar form of architecture under the nawabs who had arisen from rags to riches. As a result, architecture under the nawabs of Murshidabad deserves to be mentioned specially in a dedicated pattern, far departed from the Mughal style of architecture. The Murshidabad nawabs and their architectural idiom in India, especially grounded in Bengal, was one that had borne connections with the defining political background of British rulers too.

Bengal had forever served a pivotal place and role since prehistoric Indian history. After the culmination of the ancient era in India the medieval period and the arrival of Muslims into India from Persia was ushered in. Thus was triggered in the era of Islamic India in which the Delhi Sultanate, the Mughals, and later the Nizams or Nawabs had tremendously tried to consolidate Bengal from the far-off eastern Indian counterparts. After the departure of the Mughals, the nizams and nawabs had taken over from the indiscriminately arising `princely states`, which had given rise to an entirely different form of architecture. Indeed, Murshidabad, the once tremendous and historic stronghold in Bengal, had given birth to an entirely dissimilar form of architecture under the nawabs who had arisen from rags to riches. As a result, architecture under the nawabs of Murshidabad deserves to be mentioned specially in a dedicated pattern, far departed from the Mughal style of architecture. The Murshidabad nawabs and their architectural idiom in India, especially grounded in Bengal, was one that had borne connections with the defining political background of British rulers too.

The architectural landscape of Bengal after Aurangzeb`s death was dominated by three active groups, each responsible for different forms and types of buildings. Wealthy Hindu bankers, landholders and merchants had chiselled splendid terracotta temples in unprecedented numbers. An entire new city, Calcutta, had developed under the British in an entirely European idiom. At the same time the Mughals and their successors - the Nawabs of Murshidabad embellished their own capital, only 200 km north of Calcutta, thus ushering in a strange simultaneous era of architecture in Bengal under the Murshidabad Nawabs and beyond.

As a beginning to architecture of Murshidabad under the Nawabs, it was indeed the amirs of the Mughal court who had asserted independence with their states, in turn, lending a fresh definition to architecture in India after the departure of the Mughals. And the man in popular limelight, Murshid Quli Khan, a high-ranking amir of Mughal court, however already breached from the Mughals, had begun to carve out his own work. Architecture of Murshidabad under the nawabs had begun to take gigantic strides, which can still be witnessed to this date, with all beginning regard being attributed to Murshid Quli Khan. Murshid Quli Khan`s first architectural project in this new city was a Jami mosque constructed in 1724-25. This impressive structure, originally surmounted by five domes, is today acknowledged as the Katra mosque. Its single-aisled plan is typical of the Mughal idiom in Bengal. However, several features recall the ornamentation of pre-Mughal Bengali architecture, for instance, the facade`s numerous niches. The Jami mosque of Murshidabad under the architectural prowess of nawabs, thus stands in contrast to the more refined buildings developed in Bengal during the time of Shah Jahan or Aurangzeb. This break with the Mughal ornamental style parallels the patron`s true assertion of independence.

Surrounding the Jami mosque are domed cloistered chambers, utilised as a madrasa. The construction of this madrasa-cum-mosque, one of the very largest mosques in all Bengal, endows the city that until then had held little religious significance with a dominant sacred importance - possibly an attempt to rival the traditional centres of piety in Bengal, Gaur and Pandua. Indeed, whatever Bengal in present times, the Nawabi times in this state was one that was almost unrivalled in its each attempts. As such, Islamic architecture under the nawabs of Murshidabad, thoroughly had concentrated upon the building scenario, which was quite in the unile path that was chosen by the Mughal masters, a picture which comes to light time and again.

Surrounding the Jami mosque are domed cloistered chambers, utilised as a madrasa. The construction of this madrasa-cum-mosque, one of the very largest mosques in all Bengal, endows the city that until then had held little religious significance with a dominant sacred importance - possibly an attempt to rival the traditional centres of piety in Bengal, Gaur and Pandua. Indeed, whatever Bengal in present times, the Nawabi times in this state was one that was almost unrivalled in its each attempts. As such, Islamic architecture under the nawabs of Murshidabad, thoroughly had concentrated upon the building scenario, which was quite in the unile path that was chosen by the Mughal masters, a picture which comes to light time and again.

Less than fifty years later in the chronological order to Murshid Quli Khan`s architecture in a nawabi Murshidabad, another Jami mosque was constructed by Munni Begum, the de facto ruler and highly influential wife of the recently deceased and the ill-famed and notorious Nawab Mir Jafar. Recognised as the Chowk mosque, this elegant structure was constructed in 1767-68 in the tradition of Mughal, not pre-Mughal, mosques. The calibrated size of the five rounded domes and two end-vaults flanked by slender minarets yield an overall appearance of restrained majesty. The interior and exterior are embellished with thickly applied plaster ornament. While more elaborate than that on the earlier Burdwan tomb, stucco ornamentation on structures erected under the Murshidabad nawabs remains considerably more subdued than that on buildings built by the nawabs of Awadh. The Chowk mosque, constructed at the height of Munni Begum`s influence, was the most important religious structure in the city. Located on the ground of Murshid Quli Khan`s former audience hall, this mosque might have been envisioned as the focal point for a politically rejuvenated Murshidabad under Munni Begum`s leadership. In fact, however, the real power of Munni Begum and the succeeding nawabs had been eclipsed by the British, which is yet again a sort of foregone conclusion with regards to architecture under the nawabs of Murshidabad under the umbrella domain of Indian architecture.

From this time onwards, numerous mosques modelled on Munni Begum`s instance, were built in the city, although the embellishing motifs began to become less ornate. These mosques were almost always inscribed with the name of a patron, otherwise anonymous and unidentified, but never the name of the ruling nawab or British overlord. This suggests that mosques were no longer built as a means of gaining the favour of the ruler or of a powerful figure. Just as in the nawabs of Awadh, likewise, architecture of Murshidabad under the nawabs were verily framed and structured into religious and administrational separations. Religious construction was heavily dependant upon Islamic pattern of architecture that was begun in India, with administration later completely by the British command.

While mosques were the building type most commonly constructed in Murshidabad, two important religious complexes, each associated with the Shia sect, were built under private patronage in the late 18th and early 19th centuries. One is the Husainiya, located on the east bank of the Bhagirathi River, in close proximity to the palace. This structure was intended to house portable models (taziya) of a building associated with the martyrdom of the Prophet`s grandson, which were carried in procession at the time of Muharram. The Murshidabad Husainiya was commenced in 1804-05 and further enlarged in 1854-55. A highly placed court eunuch, Amber Ali Khan, was responsible for the initial construction, while another, Darab Ali Khan, was responsible for the later enlargement. Indeed, architecture of Murshidabad under the nawabs and their ruling pattern had smoothly conformed to the constant paradigm shift of architectural framework. Although Amber and Darab Ali Khan had built the Husainiya as private citizens, they were nevertheless intimately linked with the court. The construction and renovation of a Husainiya facilitated the celebration of a religious rite observed in Shia Islam, the sect followed by the Murshidabad nawabs. The celebration of such rites appears to have become an increasingly important aspect of official ceremony under the Murshidabad nawabs. Since all important secular and political ritual was controlled by the East India Company, it is not surprising that the nawabs might seek to foster religious ceremony. In Awadh, too, the nawabs promoted religious ceremony, having largely lost their authority over secular ritual. Such constant comparisons and gradations amongst the nawabs of both Murshidabad and Awadh and their architecture kind of had elevated the status of nawabi architecture in India, strictly following an Islamic mould.

Patronage by court eunuchs also was provided at the Murshidabad`s Qadam Sharif complex. The principal structure there is a shrine housing an impression believed to be that of the Prophet Muhammad`s foot. It was erected in 1788-89 by Itwar Ali Khan, chief eunuch of Nawab Mir Jafar. This impression, again conceived to be from Arabia, was removed from a shrine in Gaur in Bengal; before that, the impression had been housed in nearby Pandua. These cities each had served as the capital of the independent sultans of Bengal prior to Mughal times. It can be comprehended that owing to coming forth in a second order in historical chronology after the Mughals, these nawabs had been considerably overshadowed and almost eclipsed by their illustrious predecessors. Indeed, such was the influence and grandeur of Mughal architecture that, nawabi architecture in Bengal or Lucknow had constantly suffered, playing a second fiddle. As such, Islamic architecture in India in Murshidabad under the Nawabs also had walked in the same line, with the state of affairs being vastly different in two time periods. In Gaur, the shrine housing Prophet Muhammad`s foot impression had been the focus of the city`s sacral significance.

Erected during the Husain Shahi dynasty, the importance of the impression of the Prophent`s foot had continued well into the Mughal period. Thus the transfer of the footprint to Murshidabad much later was intended to bolster the religious status of the city, whose administrative and economic role had been badly undermined six years earlier when government offices were shifted to Calcutta. Just as Murshid Quli Khan, the first nawab of Murshidabad had attempted to transfer to Murshidabad the sacral significance that had been associated with Gaur, so, too, in the late 18th century, when the city`s importance was greatly diminished, a similar attempt was made. The shrine`s significance increased even more after 1858 and into the early 20th century, when it was revitalised in an attempt to infuse new life into this waning city, now almost entirely eclipsed by British power centered in Calcutta. The arrival of British in India, precisely in Calcutta, was a major and blowing stumbling block to architecture of memorable Islamic edifices. The incessant English intervention into the strictly `Indianised` administrative and religious affairs had infused umpteen problems for the Mrushidabad nawabs and their architectural brilliance. Some stray instances of betrayal and unfaithfulness towards the nawabs were also reported. As such, with Calcutta being more and more governed as the prime presidency state in British India, architecture of Murshidabad under the nawabs in late 19th and early 20th centuries also was predetermined by force by the British merciless.

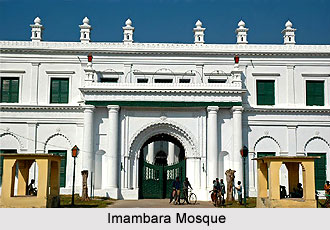

By the early 19th century, Murshidabad was the mere `nawab`s residence` and nothing more. His powers continually reduced under the repressing Britishers, he had to rely on the East India Company for his paltry annual stipend. The nawabs` utter dependence on the British is highly reflected in the residence of the nawab constructed within 1829 and 1837. Designed by a European, Duncan McLeod, the nawabi residence in Murshidabad follows the model of Government House in Calcutta, which in turn was modelled on Kedleston Hall of Derbyshire. Yet, ten years after the completion of the palace, the nawab had erected to its north an enormous Imambara signalling his autonomy in religious matters. The Imambara`s sheer size - some 80 metres longer than the palace itself - underscores the notion that the patronage of religion and religious rite were among the few means for the nawabs to exhibit authority independent of the British. However, in spite of such appalling circumstances, architecture of Murshidabad under the nawabs did continue in a flowing manner, hindrances or no hindrances, heavily in the religious sector.

According to an inscription, the patron, Nawab Feredun Jah, had appointed Sadiq Ali Khan as supervisor for the massive structure. He had designed this Imambara, the largest in eastern India, with European features, in keeping with the palace opposite. Thus the appearance of the Imambara, an official structural part of the palace, stands in marked contrast to the city`s privately patronised religious structures, all of which lack European motifs and forms, a bright glistening point in architecture of Murshidabad by the nawabs, amidst gross darkness.

That Europeanised features largely were reserved for official architecture under the nawabs in Murshidabad, which further bore additional suggestions. A rigorous Islamic architecture in India under Bengal is on the other hand suggested by another mosque commenced by the same architect who had designed the great palace Imambara. This mosque completes an understanding of architecture in Murshidabad by the nawabs and a strict nawabi India. Acknowledged as the famed Chotte Chowk-ki Masjid, it stands in an area earlier associated with Murshid Quli Khan`s palace. An inscription over the central entrance attributes its initial design and construction to Sadiq Ali. Since he had expired in 1850, much of it must have been completed by then. Contrary to what might be expected from the designer of the Imambara, this mosque is devoid of Europeanised features at a time when the near-contemporary mosques of Calcutta reveal considerable European influence. Such amalgamation and unvarying unification of the European and Islamic architectural wonders was the hallmark and superb authentication of architecture of Murshidabad in Bengal under the nawabs.

In fact, in plan and elevation the Chowk-ki Masjid resembles Mughal-period structures in Bengal dating back to Shah Jahan`s time. That is, its simple cusped arches and plain facades have more in common with earlier Mughal structures than with the ornate facades of early nineteenth-century buildings in Murshidabad. Nawabs in Murshidabad and their architecture had very much followed and come by after the Mughal Empire had faded into anonymity, which is sure to derive its charming influence from such erstwhile colossal a realm. As such Mughal characteristics are time and again visible in nawabi architecture in Bengal, specially in Murshidabad. This is characteristic of late non-imperial mosques of Murshidabad, those patronised by people other than the nawab. They adhere to forms developed in Bengal much earlier in the Mughal period. This suggests that here, as in Awadh, the architectural style developed under the Mughals came, in Mughal fragmental states, to be associated with the true architecture of devoutness, of Islam, and of the old social order - a style that by now had shed association with one or another ruling house. It was a style that stood in contrast to that erected by the rulers, increasingly predominated by Britain as much in their architecture as in their authority.