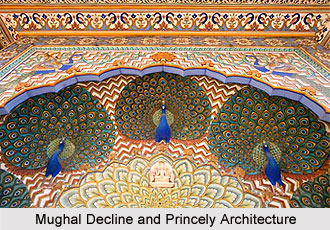

Besides western India in the form of Rajasthan and its princely rulers from states, architecture under the later Mughal rule was not only constricted down to the then Delhi or Agra, in the forms of Shahjahanabad or Fatehpur Sikri. Under the rule of the later Mughals the architecture in India mostly witnessed restoration works. As much as was assayed by these later Mughal rulers, they however never could emulate the grandeur of their forefathers. In several forms of religious institutions, burial grounds or forts, Mughal Dynasty had turned everything they touched into gold. Impressively, however, Mughal architecture continued to be the source of inspiration for architecture that flourished under other dynasties.

Besides western India in the form of Rajasthan and its princely rulers from states, architecture under the later Mughal rule was not only constricted down to the then Delhi or Agra, in the forms of Shahjahanabad or Fatehpur Sikri. Under the rule of the later Mughals the architecture in India mostly witnessed restoration works. As much as was assayed by these later Mughal rulers, they however never could emulate the grandeur of their forefathers. In several forms of religious institutions, burial grounds or forts, Mughal Dynasty had turned everything they touched into gold. Impressively, however, Mughal architecture continued to be the source of inspiration for architecture that flourished under other dynasties.

After the death of Aurangzeb, things had taken a much more shadowy and gloomier turn. Much more humbler and modest elements were being introduced under architecture of the later Mughal rulers, which was also felt in places north India itself, including Agra. Indeed, architecture of north India during later Mughals verily included places like Punjab or Rajasthan. However, Lahore was also incorporated in the then Mughal Empire, which had witnessed a much different India and its country boundary as is seen in present times. North Indian architecture under later Mughals had witnessed sizeable input from various quarters, including a free flow of massive edifices from all spheres of life.

The Mughals were able to hold Lahore and most of the Punjab until the mid-18th century, when political instability made their rule there rather tenuous. By 1768, Sikh chiefs had replaced the Mughals until the British, in turn, superseded them in 1849. Few notable monuments were erected in Punjab during the later Mughal period, possibly reflecting the unstable conditions as well as the lack of imperial intervention there. The tomb of Sharaf un-Nisa Begum, acknowledged as the Sarvwala Maqbara, or Cypress tomb, after its dominant ornamentation, is Lahore`s best-preserved monument from the post-Aurangzeb period. Indeed, time and again it is reflected that architecture of north India, spanning from Lahore to Agra during later Mughals, was quite cumbersome and one of huge worry.

The Mughals were able to hold Lahore and most of the Punjab until the mid-18th century, when political instability made their rule there rather tenuous. By 1768, Sikh chiefs had replaced the Mughals until the British, in turn, superseded them in 1849. Few notable monuments were erected in Punjab during the later Mughal period, possibly reflecting the unstable conditions as well as the lack of imperial intervention there. The tomb of Sharaf un-Nisa Begum, acknowledged as the Sarvwala Maqbara, or Cypress tomb, after its dominant ornamentation, is Lahore`s best-preserved monument from the post-Aurangzeb period. Indeed, time and again it is reflected that architecture of north India, spanning from Lahore to Agra during later Mughals, was quite cumbersome and one of huge worry.

Princely states had, prior to the death of Aurangzeb himself, asserted their domination and supremacy from severalising themselves from the gradually-collapsing Mughal Empire. As such, various Hindu rulers and Nizams had become prominent. Indeed, it can verily be stated that architecture under later Mughals in not only north India, but in various other places were established and built upon princely patronage, otherwise which nothing would never have been possible. As a consequential outcome, under the Sikhs building had accelerated considerably. Numerous new buildings, often faced with marble stripped from older Mughal structures, were erected by the new government and leading Sikh citizens. The styles of these Sikh buildings (several of them located in Lahore) correspond with those found elsewhere in contemporary north India. That is, cusped arches, fluted domes, slender carved columns and curved cornice roofs dominate. For example, the Baradari in the garden facing Lahore`s Badshahi mosque is a subtle piece of marble edifice, whose columns and cusped arches belong to the Mughal tradition. This is a square-plan pavilion constructed in 1818 by Ranjit Singh.

In this context of Mughal architecture in north India during the later Mughal rulers, the most substantial Sikh monument is located not in Lahore but in Amritsar, Punjab. Reference is being made to the scintillating Golden Temple, commenced during the late 18th century and finished largely during the 19th century. Situated in the middle of an enormous tank connected to land via a long causeway, the shrine is acknowledged as the Harimandir. This two-storeyed structure is wholly gilt-covered, glistening in the sun and lending the impression of extraordinary opulence. The temple`s square plan and two-storeyed elevation surmounted by a small domed pavilion and chattris appear to derive from Mughal tomb-types as well as some palaces, for example, the one at Datia. However, the product is characteristic of Sikh shrines alone. Other features, however, such as the fluted domes, curved cornices and multiple small domes that surmount the shrine`s parapet are pan-Indian devices of this period that have been successful enough to transcend sectarian lines. Indeed, such Sikh collaboration under the virtually dwindled Mughal Empire, was a sort of oasis to the parched traveller in frantic search of water, the result of which is still visible in the forms of architecture of a sweeping north India under later Mughals.

In this context of Mughal architecture in north India during the later Mughal rulers, the most substantial Sikh monument is located not in Lahore but in Amritsar, Punjab. Reference is being made to the scintillating Golden Temple, commenced during the late 18th century and finished largely during the 19th century. Situated in the middle of an enormous tank connected to land via a long causeway, the shrine is acknowledged as the Harimandir. This two-storeyed structure is wholly gilt-covered, glistening in the sun and lending the impression of extraordinary opulence. The temple`s square plan and two-storeyed elevation surmounted by a small domed pavilion and chattris appear to derive from Mughal tomb-types as well as some palaces, for example, the one at Datia. However, the product is characteristic of Sikh shrines alone. Other features, however, such as the fluted domes, curved cornices and multiple small domes that surmount the shrine`s parapet are pan-Indian devices of this period that have been successful enough to transcend sectarian lines. Indeed, such Sikh collaboration under the virtually dwindled Mughal Empire, was a sort of oasis to the parched traveller in frantic search of water, the result of which is still visible in the forms of architecture of a sweeping north India under later Mughals.

As can be traced from medieval Indian history, any sort of masterpiece architecture under Mughal Dynasty was very much concentrated in Agra and Delhi. The Mughals had lost control of Agra and its bordering area to the Jats early during the 18th century and were replaced by Jat and Maratha Hindu elites. However, several Muslim artisans still found patronage, since the products they originally produced were now demanded by the new Hindu elite, ensuring a continuity of style. Little Muslim construction was witnessed in this area during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, but temples, palaces and gardens constructed under Hindu patrons had now begun to embellish the Agra region. This area had flourished under these new rulers, while they constructed their headquarters at Dig, Bharatpur and other localities. The area`s association with the birthplace and childhood of Lord Krishna further had stimulated its vigorous revitalisation. For instance, members of the Jaipur royal family are credited with providing a number of temples in Brindavan, while the subsequent Jat rulers of the area also maintained these structures and added their own as well. Nearby in Govardhan, multi-stoned cenotaphs embellished with cusped arches, bangala-roofed pavilions and ribbed domes were built to memorialise the rajas of Bharatpur.

However, by far the most impressive architectural work in north India during the later Mughals is the palace at Dig in Bharatpur District. It was constructed as the new Jat headquarters under Badan Singh (1722-56) and his family, most notably Suraj Mal (1756-63) and his successors. Although built in several stages and under different patrons, the palace and its garden setting adhere to a symmetrical formality derived strictly from Mughal gardens. A central square char bagh is surmounted on all four sides by pavilions, recalling the organisation of Mughal gardens. The palace pavilions are characterised by an air of solidity and grace. Badan Singh`s portion of the palace, acknowledged as the Purana Mahal, consists of a series of rectangular pavilions surmounted by deeply sloped curved roofs topped with spiked finials, producing a highly articulated yet elegant skyline. Another portion of the Dig palace is the much-recognised Keshav Bhavan.

However, by far the most impressive architectural work in north India during the later Mughals is the palace at Dig in Bharatpur District. It was constructed as the new Jat headquarters under Badan Singh (1722-56) and his family, most notably Suraj Mal (1756-63) and his successors. Although built in several stages and under different patrons, the palace and its garden setting adhere to a symmetrical formality derived strictly from Mughal gardens. A central square char bagh is surmounted on all four sides by pavilions, recalling the organisation of Mughal gardens. The palace pavilions are characterised by an air of solidity and grace. Badan Singh`s portion of the palace, acknowledged as the Purana Mahal, consists of a series of rectangular pavilions surmounted by deeply sloped curved roofs topped with spiked finials, producing a highly articulated yet elegant skyline. Another portion of the Dig palace is the much-recognised Keshav Bhavan.

The styles of the structures at nearby Mathura, built during the period of British supremacy, are analogous to contemporary material in Delhi and Rajasthan. Amongst these is a cenotaph built as a memorial to one deceased Hindu, Parikhji, who had expired in 1837. In plan, it is similar to the octagonal tomb-type of the Lodi and Sur kings. The ornamentation, however, is typical of 19th century architecture here and in Delhi. Cenotaphs such as this were originally associated only with Muslim custom. Then, around the 16th century, they were erected by some of the Hindu princely families of Rajasthan to commemorate and remember their ancestors. This cenotaph in Mathura has been adjusted to non-royal Hindu use, dimming the distinction in architecture reserved for one religion or another, as well as that reserved for the monarch on the one hand and his subjects on the other. Indeed, the conscious and at times unconscious blending and merging of `Hinduistic` and Islamic structural frame, had gone ahead to become one of the most striking feature of architecture during later Mughals not only in north India, but also in other parts of the country. However, if stated in a detailed format, architecture of north India during and under the last Mughals was principally destined and decided in Agra, the pivot of all Mughals since the advent of Babur from Persia.