Emperor Akbar is generally recognised as the greatest and most able of the Mughal rulers that the Mughal Empire had ever conceived. From his time to the end of the Mughal period, artistic architecture production on both an imperial and sub-imperial level were intimately associated with notions of state polity, religion and kingship. Indeed, architectural production under Akbar in their regal capitals of Delhi and Agra was a matter which always had demanded the most of his attention, proofs of which can still be witnessed to this date, in all their glory, grandeur and magnificence. Delhi had always served as the most convenient and befitting a place for the establishment of the Mughal Empire, due to which it had remained in the prime limelight, in every matter related to administration and architecture. As such, architecture in Delhi during Akbar was not an issue which can just be laid to the sidelines in order to establish more important facts of the Mughal dominion. Indeed, much and more of that can be stated in connection to the Mughal architecture of Delhi under Akbar, which is still a matter of significant research and admiration for public eye.

Emperor Akbar is generally recognised as the greatest and most able of the Mughal rulers that the Mughal Empire had ever conceived. From his time to the end of the Mughal period, artistic architecture production on both an imperial and sub-imperial level were intimately associated with notions of state polity, religion and kingship. Indeed, architectural production under Akbar in their regal capitals of Delhi and Agra was a matter which always had demanded the most of his attention, proofs of which can still be witnessed to this date, in all their glory, grandeur and magnificence. Delhi had always served as the most convenient and befitting a place for the establishment of the Mughal Empire, due to which it had remained in the prime limelight, in every matter related to administration and architecture. As such, architecture in Delhi during Akbar was not an issue which can just be laid to the sidelines in order to establish more important facts of the Mughal dominion. Indeed, much and more of that can be stated in connection to the Mughal architecture of Delhi under Akbar, which is still a matter of significant research and admiration for public eye.

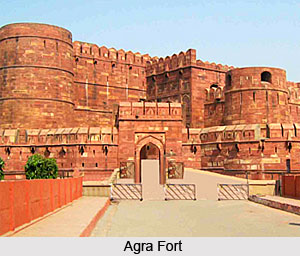

Delhi, the traditional capital of north Indian Islamic rulers, very much had served as Akbar`s capital until 1565, when he had commenced his massive Agra Fort. This was followed by the construction of other forts in strategically important locations, signalling the diminishing importance of Delhi, until its revival in the mid-seventeenth century. Historically, thus, architecture of Delhi during Akbar grips prime importance for one to comprehend his panache of building and passion of patience.

Timurid features are often evident in some of the most important Akbari architectural buildings in Delhi, including his finest work there, his father`s tomb (referring to the exquisite Humayun`s Tomb). Many of these features are, however, largely dropped in Akbar`s buildings constructed after moving the capital to Agra. Amongst the works that recall architecture in the Mughal homeland is the Sabz Burj, located south of the citadel of Humayun`s Tomb. The tomb is probably a product of Akbar`s reign, although it may date as early as Humayun`s reign too. It is designed as a Baghdadi octagon, with a high dome resting on an elongated neck; originally green tiles covered its surface. Architecture of Delhi during Akbar was thus a kind of crowning glory to Mughal dynastic architecture and the upholding of its tradition.

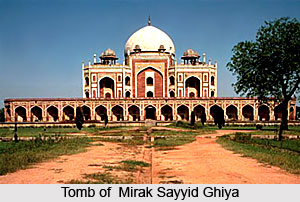

At least as clearly based on Timurid prototypes is the largest structure erected in Delhi during the early years of Akbar`s reign - the tomb of the deceased emperor Humayun. Situated just south of the Din-Panah citadel and in close proximity to the esteemed dargah of Nizam ud-Din, the mausoleum Humayun`s Tomb even today dominates its surroundings. A contemporary Mughal source indicates that the tomb was finished in 1571 after eight or nine years of rigorous work. Tradition states that a devoted wife, Hajji Begum, was responsible for its construction; recently, however, Akbar had been proposed as the patron, even though the tomb resembles none of Akbar`s other architectural enterprises in Delhi. Humayun`s Tomb`s Timurid appearance must be credited to its Iranian architect, trained in the Timurid tradition and acknowledged from contemporary texts as both Mirak Sayyid Ghiyas and Mirak Mirza Ghiyas. His masterpiece came to be influential in the design of Mughal mausoleum through the 18th century. Evidence still persists that Humayun`s Tomb truly assists architecture in Delhi during Akbar to be elevated towards pinnacle heights.

At least as clearly based on Timurid prototypes is the largest structure erected in Delhi during the early years of Akbar`s reign - the tomb of the deceased emperor Humayun. Situated just south of the Din-Panah citadel and in close proximity to the esteemed dargah of Nizam ud-Din, the mausoleum Humayun`s Tomb even today dominates its surroundings. A contemporary Mughal source indicates that the tomb was finished in 1571 after eight or nine years of rigorous work. Tradition states that a devoted wife, Hajji Begum, was responsible for its construction; recently, however, Akbar had been proposed as the patron, even though the tomb resembles none of Akbar`s other architectural enterprises in Delhi. Humayun`s Tomb`s Timurid appearance must be credited to its Iranian architect, trained in the Timurid tradition and acknowledged from contemporary texts as both Mirak Sayyid Ghiyas and Mirak Mirza Ghiyas. His masterpiece came to be influential in the design of Mughal mausoleum through the 18th century. Evidence still persists that Humayun`s Tomb truly assists architecture in Delhi during Akbar to be elevated towards pinnacle heights.

Today, the tomb complex is entered by an enormous gate on the west, although during Mughal times the southern gate was widely utilised. Upon entering any gate, the centrally situated tomb and its illustrious char bagh settings are visible as a masterwork. Each of the four garden plots is further sub-divided by narrower waterways. Based on the char bagh kinds established in Iran and more fully developed during Babur`s own concept of the ideal garden, such formalised and geometrically planned garden settings became standard for all the imperial Mughal mausolea and for those of many nobles as well. Indeed, Humayun`s Tomb stands as an ideal insignia for architecture of Delhi during Akbar, which had introduced several firsts for Mughal architectural excellence. Char bagh gardens long had been associated with paradisiacal imagery. But at Humayun`s Tomb, the association is all the more explicit, for the water channels appear to vanish beneath the actual mausoleum yet reappear in their same straight course on the opposite side. This evokes a Quranic verse which describes rivers flowing beneath gardens of paradise.

The mausoleum is square in plan, 45 metres on a side. Crowned with a white marble bulbous dome and flanking chattris, the tomb sits on a high elevated plinth 99 metres per side. Each facade, faced with red sandstone and trimmed with white marble, is almost identical and meets at chamfered corners. The west, north and east facades of Humayun`s Tomb are marked by a high central portal, flanked on either side by lower wings with deeply recessed niches. The south entrance, probably the principal one, consists of lower wings on either side of a high central pishtaq, underneath which is a deeply recessed niche. The seeming simplicity of this tomb`s exterior is indeed belied by the interior, yet another brilliant innovation to the already-elevated architecture of Delhi during Akbar and his limit to stretch his intellect.

There, on the ground floor, the mausoleum possesses a central octagonal chamber containing a cenotaph. This chamber is surrounded by eight ancillary rooms, a radical departure from the single chamber of earlier Indian tombs. Passages connect these smaller chambers with the main one and with the outside. The second storey of the tomb is similar. Such a spatial arrangement is based on geometric principles first applied in Timurid architecture and seen in structures such as the Ishrat Khana built approximately in 1464 and utilised as a dynastic mausoleum for women. These eight ancillary chambers are intended to evoke the paradises of Islamic cosmology. The passages connecting them are probably intended to facilitate circumambulation of the cenotaph in the central chamber. This ritual, drawn from Sufi rites, was a common practice at Mughal imperial tombs, certainly denoting Akbar`s religious bent of mind and a meritorious architectural build in Delhi.

There, on the ground floor, the mausoleum possesses a central octagonal chamber containing a cenotaph. This chamber is surrounded by eight ancillary rooms, a radical departure from the single chamber of earlier Indian tombs. Passages connect these smaller chambers with the main one and with the outside. The second storey of the tomb is similar. Such a spatial arrangement is based on geometric principles first applied in Timurid architecture and seen in structures such as the Ishrat Khana built approximately in 1464 and utilised as a dynastic mausoleum for women. These eight ancillary chambers are intended to evoke the paradises of Islamic cosmology. The passages connecting them are probably intended to facilitate circumambulation of the cenotaph in the central chamber. This ritual, drawn from Sufi rites, was a common practice at Mughal imperial tombs, certainly denoting Akbar`s religious bent of mind and a meritorious architectural build in Delhi.

Humayun`s Tomb`s adherence to geometric principle and the complexity of its internal organisation bear a clear imprint of Timurid tradition. This is not surprising since the architect himself had worked extensively in Bukhara, the last bastion of Timurid artistic traditions. Architecture in Delhi during Akbar was thus a significant phase which was still a dazzling carry over from a Persian Timur and his subsequent Timurid influences. Coupled with the fact that Humayun and his wife had long been exiled in Iran and developed a taste for an Iranian aesthetic, this easily explains the tomb`s appearance. Moreover, the Mughals were extremely proud of their Timurid ancestry and it is not without significance that this Timund-inspired tomb and setting continued for the most part to serve as an important model for imperial tombs.

Shifting the imperial headquarters from Delhi did not signal its abandonment by either the emperor or highly influential court members. For instance, Akbar in 1571 had visited his father`s tomb upon its completion and in 1572-73 gave orders for the restoration of the Jamaat Khana mosque at the Nizam ud-Din dargah. In 1575-76, Akbar`s chief theologian (sadr) Shaikh Abd ul-Nabi Khan, who wielded tremendous power until his fall from favour about 1580, had constructed a mosque not in Agra or Fatehpur Sikri, then imperial residences, but in Delhi, suggesting that the city still was envisioned as a major urban centre. Indeed, whatever Agra might have been in Mughal times, architecture in Delhi during Akbar always shall stand out as a memorable completion of something unimaginable in contemporary times. This mosque by Shaikh Abd ul-Nabi Khan, situated north of the Mughal Din-Panah, closely resembled Maham Anga`s madrasa, although today few of its original features remain. The structure`s epigraph, composed by Akbar`s poet laureate, Faizi, the brother of Abu ul-Fazl, does not specifically identify the structure`s function, but its close adherence to the earlier madrasa suggests that it was intended as a theological school, suggesting Delhi`s continual role as an intellectual centre.