Architecture in Bengal during Mughal emperor Akbar grandly comes under the category of sub-imperial patronage, a legacy which was mastered to the fullest since the times Babur himself, however with much potentiality since Akbar. During Akbar`s reign imperially sponsored architecture very much had incorporated Timurid design concepts with forms, motifs and building techniques long indigenous to Indian architecture. Many of the resulting buildings, for instance much of the palace at Fatehpur Sikri, are highly refined products of prevailing Indian tastes, although the organisation and spatial arrangements owe much to Timurid concepts. Akbar, like Humayun, was little involved with religious architecture with the exception of the great khanqah at Fatehpur Sikri. He primarily had built forts and palaces - building types that reflect his concept of the Mughal state. The function of many parts of his palaces is often impossible to determine, reflecting the `fluid nature` of court ceremony during Akbar`s reign. Akbar also had continued to build char baghs, initially introduced to India by Babur. The tomb he had built for his father, Humayun, is the first to be set in such a garden. Every kind of Akbar`s Mughal architectural pattern was later on move on to become a Mughal architectural concern, which gradually was lapped up by his patronised nobility in erecting edifices in far-off places like Bengal in Eastern India.

Architecture in Bengal during Mughal emperor Akbar grandly comes under the category of sub-imperial patronage, a legacy which was mastered to the fullest since the times Babur himself, however with much potentiality since Akbar. During Akbar`s reign imperially sponsored architecture very much had incorporated Timurid design concepts with forms, motifs and building techniques long indigenous to Indian architecture. Many of the resulting buildings, for instance much of the palace at Fatehpur Sikri, are highly refined products of prevailing Indian tastes, although the organisation and spatial arrangements owe much to Timurid concepts. Akbar, like Humayun, was little involved with religious architecture with the exception of the great khanqah at Fatehpur Sikri. He primarily had built forts and palaces - building types that reflect his concept of the Mughal state. The function of many parts of his palaces is often impossible to determine, reflecting the `fluid nature` of court ceremony during Akbar`s reign. Akbar also had continued to build char baghs, initially introduced to India by Babur. The tomb he had built for his father, Humayun, is the first to be set in such a garden. Every kind of Akbar`s Mughal architectural pattern was later on move on to become a Mughal architectural concern, which gradually was lapped up by his patronised nobility in erecting edifices in far-off places like Bengal in Eastern India.

Akbar primarily had built at his capitals and also defensively at the major cities on the frontier of his domain, such as Allahabad. But Mughal architecture under Emperor Akbar was not confined to these places; rather, it had expanded to the hinterlands. There, though, the architecture was given life not by the emperor but by his nobles, whose taste most often echoed that of the centre. In this expanding Mughal Empire, architecture increasingly had served as a symbol of Mughal presence; as such, architecture in Bengal during Akbar under the noblemen of the Mughal court, had sought to establish a name for themselves in an unprecedented manner.

Until 1575, Bengal verily was under the control of various Afghan houses. Later, Akbar`s troops had brought Bengal into the Mughal Empire. Subsequently, several revolts against Akbar`s authority were staged by renegade nobles of the Mughal camp. Ironically, during this chaotic period, a Mughal style of architecture was introduced by the rebels, kind of uncannily amalgamating architecture of Bengal under Akbar with an Afghan rebellious one.

Bengali Islamic architecture since long had possessed a marked regional character. It was founded on a well-established Islamic style in Bengal, illustrated by several monuments constructed on the eve of Mughal authority there. Amongst these are the double-aisled six-domed mosque of Kusumba built in 1558-59 and the square-plan single-domed tomb of Pir Bahram in Burdwan, dated 1562-63. The former is an instance of being stone-faced, while the latter is brick-constructed and both, like most pre-Mughal architecture of Islamic Bengal, possessed a prominent curved cornice. Their plan and elevation - even the ornamental brick - reflect forms that were at the time several centuries old. From this foundation, the Mughal architectural style of Bengal during Akbar had evolved.

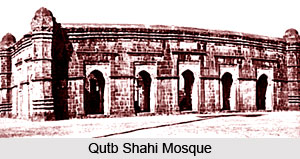

However, architecture of Bengal during Akbar, as a strict Mughal architectural pattern in Bengal, had to firstly contend with these said Afghan generals and their zeal to seize prominence. Only five years after the establishment of Mughal authority in Bengal and before any known Mughal building had been erected there, Afghan chiefs had revolted against Mughal authority and assumed power. The Afghan Masum Khan Kabuli, a renegade Mughal noble, had declared himself ruler of Bengal, even though the imperial Mughals are known to have maintained nominal control. By 1581, Madura Khan Kabuli had assumed the title of sultan, as indicated by an inscription on the first surviving Mughal monument in Bengal, the Jami mosque in Chatmohar (Pabna District). Approximately one year later, in 1582, two mosques were constructed, each reflecting divergent stylistic traditions. The Qutb Shahi mosque of 1582-83 in Pandua, built by Makhdum Shaikh in honour of the long-deceased but deeply revered saint, Nur Qutb Alam, adheres to a plan popular in Bengal since the 14th century.

This stone-faced Qutb Shahi mosque is divided into two aisles of five bays each. Not only it is constructed in the traditional Bengali style, but also the inscription is in Arabic - the language of most pre-Mughal inscriptions in Bengal. This is the last stone-faced mosque built in Bengal until the 20th century and it is the last small double-aisled rectangular mosque constructed in Bengal until the 19th century. A different trend is represented by the single-aisled, three-bayed plan of the Kherua mosque in Sherpur (Bogra District), also built in 1582, yet another Mughal architectural pattern in architecture of Bengal during Akbar. Its patron was Murad Khan, son of Jauhar Ali Khan Qaqshal. The Qaqshal were an Afghan tribe that, along with other Afghan groups who followed Masum Khan Kabuli, sought to oust the Mughals from Bengal. Sherpur, the city in which the mosque is situated, had served as the rebel headquarters. Ironically, however, it was this mosque-type that became standard in Mughal and post-Mughal Bengal.

This stone-faced Qutb Shahi mosque is divided into two aisles of five bays each. Not only it is constructed in the traditional Bengali style, but also the inscription is in Arabic - the language of most pre-Mughal inscriptions in Bengal. This is the last stone-faced mosque built in Bengal until the 20th century and it is the last small double-aisled rectangular mosque constructed in Bengal until the 19th century. A different trend is represented by the single-aisled, three-bayed plan of the Kherua mosque in Sherpur (Bogra District), also built in 1582, yet another Mughal architectural pattern in architecture of Bengal during Akbar. Its patron was Murad Khan, son of Jauhar Ali Khan Qaqshal. The Qaqshal were an Afghan tribe that, along with other Afghan groups who followed Masum Khan Kabuli, sought to oust the Mughals from Bengal. Sherpur, the city in which the mosque is situated, had served as the rebel headquarters. Ironically, however, it was this mosque-type that became standard in Mughal and post-Mughal Bengal.

The Kherua mosque`s single-aisled, three-bayed plan recalls not only north Indian types, but also that of Habash Khan`s mosque of 1578 built in Rohtas. While Bengali features remain, such as the brick construction, curved cornice and engaged ribbed corner turrets, the plan is a whole divergence from that of traditional Bengali mosques. This may be attributed to the fact that the ruler, Masum Khan Kabuli, and many of his rebel followers who had served earlier in Bihar under the Mughals, were familiar with north Indian forms, as well as with the mosques in the great stronghold of Rohtas. When serving the Mughals they had assisted with the fort`s initial takeover and later tried to capture Rohtas for themselves. It gradually becomes a much comprehended fact that these Afghan rebels, espousing under the Mughal realm, had sought to build an architecture which would aptly compliment a strict Mughal architectural pattern established in east India. As a result, Mughal architecture in Bengal under Akbar was not wholly a `rebellious endeavour` after all.

Older Hindu sculptures are known to have been imbedded in the Kherua mosque`s east facade, leaving only the back visible; that part was carved with a Persian inscription. Re-usage of Hindu materials in such a prominent fashion is rare in Bengal after the 14th century; the Qaqshal rebels were probably cut off from sources of freshly quarried stone, which would have been used for an inscription on a brick monument, and so had to rely on available materials. This, as much as desecration of a Hindu shrine, probably explains the images` use. Both epigraphs are scripted in Persian - the lingua franca of the Mughal court, rather than Arabic, more common in Bengal. This is yet another indication that Bengali architecture under Akbar was moving closer to a `pan-Indian` idiom whose standards were established at imperial centres. Due to their former association with the Mughal court, the Qaqshal, now rebels, were nevertheless planting the seeds in Bengal of an architectural vocabulary that would become standard throughout the subcontinent from the 17th century onwards.

While the language of the inscriptions in the mosques described, is characteristic of Mughal epigraphs, the content of these inscriptions is unusual. However, it is perhaps apt for a mosque constructed by rebels. The inscription, still in its original site in the Kherua mosque, recounts the story of two pigeons from Mecca, a metaphor for the rebel Qaqshal, who had requested shelter for themselves and for their friends from a faqir. The faqir had granted the permission, but had stated that the mosque is small and would not shelter them from violence. In response, the pigeons had replied that God`s wrath would be great if the mosque or pigeons were harmed. The second inscription, no longer however in their original site and position, also admonishes protection of the mosque. Such a plea for protection is appropriate to the world of rebels and appears to have been taken seriously, for the Kherua mosque remains still in excellent preservation. The otherwise unknown Nawab Mirza Murad Khan Qaqshal is wholly remembered for erecting the first acknowledged Bengali mosque of a type that was to become popular throughout Bengal`s architecture during and under Akbar.

While the language of the inscriptions in the mosques described, is characteristic of Mughal epigraphs, the content of these inscriptions is unusual. However, it is perhaps apt for a mosque constructed by rebels. The inscription, still in its original site in the Kherua mosque, recounts the story of two pigeons from Mecca, a metaphor for the rebel Qaqshal, who had requested shelter for themselves and for their friends from a faqir. The faqir had granted the permission, but had stated that the mosque is small and would not shelter them from violence. In response, the pigeons had replied that God`s wrath would be great if the mosque or pigeons were harmed. The second inscription, no longer however in their original site and position, also admonishes protection of the mosque. Such a plea for protection is appropriate to the world of rebels and appears to have been taken seriously, for the Kherua mosque remains still in excellent preservation. The otherwise unknown Nawab Mirza Murad Khan Qaqshal is wholly remembered for erecting the first acknowledged Bengali mosque of a type that was to become popular throughout Bengal`s architecture during and under Akbar.

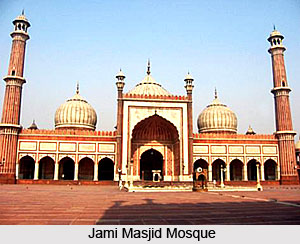

Elsewhere in Bengal, architectural activity during Akbar`s time was confined largely to Rajmahal, the capital, where the Rajput Raja Man Singh was active. However, in Malda, a large trade city that benefited from the prosperity of the important shrines in nearby Pandua, a Jami mosque was erected in 1595-96, shortly after Raja Man Singh had assumed the governorship of Bengal. This was a period when the Mughals had begun to have some effect in crushing the dissident rebel forces. In the Jami mosque`s inscription, neither the patron nor the ruling monarch is recorded. It does, however, identify the mosque`s location as in "Hind," an area approximately corresponding to north India. This reveals identity with the territory then ruled by the Mughals and not just Bengal.

The Malda Jami mosque, a much noted architecture of Bengal during Akbar and his patronage, demonstrates an increasing adoption of north Indian forms. The interior emotes a sense of open space, rarely seen in Bengali rectangular mosques, but common in north Indian examples. The central vaulted corridor is derived from Bengali prototypes, for instance the Adina and Gunmant mosques, while north Indian influence is witnessed in the single-aisled plan. The mosque`s ornamentation, too, demonstrates a heightened awareness of north Indian models, for, both the facade and interior are largely plastered with a smooth stucco veneer, reminiscent, for example of Humayun`s mosque in Kachpura.

The construction of this large Jami mosque in Malda suggests the continued economic significance of Malda, despite political turmoil. This is not surprising, for urban centres not wholly created as political centres tend to survive administrative changes, wars and even natural calamity. The most notable Mughal monument in Malda is a tower acknowledged in present times as the Nim Serai Minar. Located across the river from the Jami mosque, this minaret or tower is aligned with the mosque`s qibla wall, the west-facing one. The location of this Nim Serai tower, on a hill overlooking the confluence of two rivers - during that time considered as major transport routes, suggests that it also may have served as a watch tower, with Fatehpur Sikri time and again coming up as a serving instance to architectural by Akbar in Bengal in eastern India, so much far away from Agra.

The Nim Serai Minar`s facade is covered with stone projections, resembling elephant tusks, similar to those on the tower again in Fatehpur Sikri. Overall, the Malda tower`s form recalls the earlier Chor Minar in Delhi, employed to display the heads of thieves. It is thus possible that the Malda tower was constructed when Mughal governors in Bengal were subduing rebel forces and here were of the habit to display rebel heads, a custom earlier practiced by the Mughal forebear, Timur. As a conclusion architecture in Bengal during Akbar was accomplished under circumstances of great turmoil and disturbance, with Mughal chiefs at times busy with quashing the rebel Afghan forces, who had assayed to frame a Mughal architectural idiom of their own. However, the finished product that one witnesses today, very much is reminiscent of Akbar`s Mughal architectural expression, which was thoroughly grounded in architecture of Bengal, with opulence speaking out from each angle.