Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and the `Islamisation of the Mughal style` was a completely new genre that was witnessed after the demise of Shah Jahan. Indeed, Mughal architecture during Aurangzeb reflected the man`s private doctrine. Islam was thoroughly preached and propagated during his times. Architecture in Ajmer during Aurangzeb was a gross new pattern, which was previously not witnessed under the first Mughals. Indeed, Ajmer`s architecture under Aurangzeb can largely be grouped into a `later Mughal` illustration, shorn of past grandeur. All the same, under Aurangzeb and his successors the framework of earlier architectural patronage was changed entirely. To be precise, under the earlier Mughals the emperor was counted as the `model patron`. The nobility, the bunch of viziers at the Mughal court, generally regarded the type of structures the emperor built and the styles he favoured as the ideal to emulate. Under Aurangzeb however, and especially under his successors, that state of affairs had changed. There could be witnessed no dynamic imperial patron, so the nobility and other classes used to build independently of strong central direction, often employing styles and motifs that still echoed those established during Shah Jahan`s reign.

Mughal emperor Aurangzeb and the `Islamisation of the Mughal style` was a completely new genre that was witnessed after the demise of Shah Jahan. Indeed, Mughal architecture during Aurangzeb reflected the man`s private doctrine. Islam was thoroughly preached and propagated during his times. Architecture in Ajmer during Aurangzeb was a gross new pattern, which was previously not witnessed under the first Mughals. Indeed, Ajmer`s architecture under Aurangzeb can largely be grouped into a `later Mughal` illustration, shorn of past grandeur. All the same, under Aurangzeb and his successors the framework of earlier architectural patronage was changed entirely. To be precise, under the earlier Mughals the emperor was counted as the `model patron`. The nobility, the bunch of viziers at the Mughal court, generally regarded the type of structures the emperor built and the styles he favoured as the ideal to emulate. Under Aurangzeb however, and especially under his successors, that state of affairs had changed. There could be witnessed no dynamic imperial patron, so the nobility and other classes used to build independently of strong central direction, often employing styles and motifs that still echoed those established during Shah Jahan`s reign.

Mughal dynastic architecture during Aurangzeb in Ajmer was one which was as normal, utilised the most and the first in the esteemed and celebrated dargah of Muin ud-Din Chisthi. Aurangzeb in known to have paid homage on several occasions at the dargah of Muin ud-Din Chishti and had continued his predecessors` practice of generously distributing alms there; significantly enough, he did not, however, add any structures to the shrine. One instance of architecture by Aurangzeb in Ajmer however, can be witnessed to have been built during his reign. Shaikh Ala ud-Din, who until his demise was in charge of the shrine, had erected his tomb in 1659-60 just outside the shrine on its west. Acknowledged as the Sola Khamba, this rectangular marble building derives its name from the sixteen columns that support its cusped entrance arches. Its three mihrabs (a niche in the wall of a mosque that indicates the qibla, i.e., the direction of the Kaaba in Mecca and hence the direction that Muslims should face when praying. The wall in which a mihrab is sighted, is thus the "qibla wall") are closely modelled on the central one of Shah Jahan`s marble mosque immediately to the tomb`s east, again emphasising the impact of this mosque on the subsequent architecture of Ajmer during and post Aurangzeb. The Sola Khamba, however, introduces cusping, not seen on Shah Jahan`s public architecture in Ajmer. This and the increasing number of columns supporting these cusped arches expose an elaboration and thorough embellishment of form common to Aurangzeb-period works.

Another structure bearing the impact of Shah Jahan`s Jami mosque is one which was provided in 1692-93 close to the dargah by Sayyid Muhammad, an attendant (mutawali) at the saint`s tomb. Unlike the Shah Jahan-period mosques on the same street, this small single-aisled mosque - a humble offering of Aurangzeb and his architecture in Ajmer, is not on ground level, but located above the shops, following contemporary practice in Delhi. It bears several inscriptions, including a lengthy Persian one inlaid with black stones into a white marble ground. This elegant inscription, designed by Naji, a well-known poet and calligrapher of Aurangzeb`s time, is similar in appearance, location and design to the one on Shah Jahan`s mosque at the shrine. The mosque itself is a simple yet elegant structure whose facade consists of three cusped arches supported on polygonal columns, a form typical of Aurangzeb-period architecture in Ajmer.

Ranking in quality with imperial works is yet another exquisite white marble tomb believed to be that of the wife of Abdullah Khan. He was the father of the renowned Sayyid brothers, who after Aurangzeb`s reign were acknowledged as the `king-makers`. Abdullah Khan`s wife`s tomb is modelled most intimately on those built for imperial princesses, for instance, the tomb of Jahan Ara (eldest daughter to Shah Jahan). Like that tomb, the present tomb`s (referring to Abd Allah Khan`s wife`s tomb) cenotaph, surmounted by finely carved screens, is left open to the air. Indeed, it is very well visible that architecture of Ajmer during Aurangzeb presented a scenario which was to become crucial in later times of downfall of the Mughal Empire. Other inscriptions on the tomb of Abdullah Khan indicate that a mosque and garden were built in conjunction with the tomb between 1702 and 1704. Later in 1710, Abdullah`s tomb in the same compound was erected by his sons.

Ranking in quality with imperial works is yet another exquisite white marble tomb believed to be that of the wife of Abdullah Khan. He was the father of the renowned Sayyid brothers, who after Aurangzeb`s reign were acknowledged as the `king-makers`. Abdullah Khan`s wife`s tomb is modelled most intimately on those built for imperial princesses, for instance, the tomb of Jahan Ara (eldest daughter to Shah Jahan). Like that tomb, the present tomb`s (referring to Abd Allah Khan`s wife`s tomb) cenotaph, surmounted by finely carved screens, is left open to the air. Indeed, it is very well visible that architecture of Ajmer during Aurangzeb presented a scenario which was to become crucial in later times of downfall of the Mughal Empire. Other inscriptions on the tomb of Abdullah Khan indicate that a mosque and garden were built in conjunction with the tomb between 1702 and 1704. Later in 1710, Abdullah`s tomb in the same compound was erected by his sons.

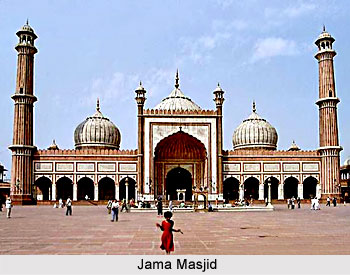

Even structures outside the closest vicinity of Ajmer reveal an awareness of current Mughal idiom. Amongst these is the Jami mosque in Merta, approximately 100 km north of Ajmer. It was built by Hajji Muhammad Sultan, the son of a local religious official, in 1665. The mosque, constructed in local red stone, is placed atop a high plinth above shops, a classical instance that was followed in Ajmer`s architecture during Aurangzeb. Very tall minarets, visible from a considerable distance, promote and announce its presence, as do its three bulbous domes. The central one owns a tightly constricted neck and is faced with alternating red and white stripes, like those on Shah Jahan`s Jami mosque in Shahjahanabad, built almost a decade earlier (referring to the historic Jama Masjid of Old Delhi). The overall effect is a potential emphasis on verticality and a clear sense of spatial tension, such as was seen a few years earlier at the Bibi-ka Maqbara in Aurangabad and the Jami mosque in Mathura - both products of 1660-61. Such was the bounteous beauty of architecture in Ajmer during and under Aurangzeb, with the latter instance pertaining to the respectable rise of imperially patronaged architectural works dominating the Mughal Indian skyline.