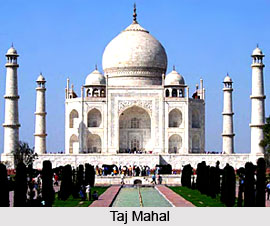

Shah Jahan`s active involvement in the design and production of Mughal architecture had far exceeded that of any other Mughal emperor. Themes initially established in the buildings of his predecessors were finely honed and reached maturity under Shah Jahan. For instance, the long-standing notion that imperial Mughal mausoleum were symbols of paradise was manifest most precisely and imposingly in the Taj Mahal. More than any other ruler, Shah Jahan had sought to use architecture to project the emperor`s formal and `semi-divine` character. He did so, in part, by adapting motifs found in western art and indigenous Indian architecture, such as the baluster column and baldachin covering, giving them a unique imperial context. The `charged` meaning of these motifs, however, is only found in Shah Jahan`s reign, for they are seen on the earliest non-imperial structures of his successor`s reign. He had built many more mosques than did his predecessors and used this building type to project his official image as the `upholder of Islam`. This is indeed a trend which had accelerated under Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan`s son and successor. Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan was one over-the-top and beyond personified endeavour, which was so very much unprecedented, that no other earthly creations could indeed stand neck to neck under any circumstances. So much so was Shah Jahan`s Mughal architectural impression upon the then Indian society, that the edifices` enormity, magnanimity, massiveness or flamboyance, that every structure loomed over from atop a hill.

Shah Jahan`s active involvement in the design and production of Mughal architecture had far exceeded that of any other Mughal emperor. Themes initially established in the buildings of his predecessors were finely honed and reached maturity under Shah Jahan. For instance, the long-standing notion that imperial Mughal mausoleum were symbols of paradise was manifest most precisely and imposingly in the Taj Mahal. More than any other ruler, Shah Jahan had sought to use architecture to project the emperor`s formal and `semi-divine` character. He did so, in part, by adapting motifs found in western art and indigenous Indian architecture, such as the baluster column and baldachin covering, giving them a unique imperial context. The `charged` meaning of these motifs, however, is only found in Shah Jahan`s reign, for they are seen on the earliest non-imperial structures of his successor`s reign. He had built many more mosques than did his predecessors and used this building type to project his official image as the `upholder of Islam`. This is indeed a trend which had accelerated under Aurangzeb, Shah Jahan`s son and successor. Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan was one over-the-top and beyond personified endeavour, which was so very much unprecedented, that no other earthly creations could indeed stand neck to neck under any circumstances. So much so was Shah Jahan`s Mughal architectural impression upon the then Indian society, that the edifices` enormity, magnanimity, massiveness or flamboyance, that every structure loomed over from atop a hill.

Shah Jahan`s precise Mughal architectural style is deeply rooted in the buildings of his predecessors. The tomb of Mumtaz Mahal marks a return to Humayun`s Timurid tomb-type and indeed the interest in elaborate Timurid vaulting types is heightened in Shah Jahan`s reign. Trabeated pavilions, as seen in earlier Mughal reigns, grace Shah Jahan`s palaces, hunting estates and gardens. Under Shah Jahan`s rule, however, there is an emphasis unprecedented in Mughal architecture on the structure`s graceful lines and a harmonious balance among all the parts. Shah Jahan`s personal involvement in architecture and city planning appears to have motivated others, especially the high-ranking women of his court, to build. While the emperor had provided palace buildings and forts, these women and the nobility had acquired responsibility for embellishing the cities. Nowhere is this seen more clearly than in his de novo city, Shahjahanabad, where mosques, gardens, markets, serais and mansions were provided by the aristocracy. This emperor was so much a man with intelligence par excellence, that Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan endeavouring to reach the peak, had in fact achieved the peak, irrespective of hostilities.

Although Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan is incredibly epitomised and personified for love and affection for the construction of the Taj Mahal - included in the prestigious list of the New Seven Wonders of the World, yet, the other architectural masterpieces are not exactly overshadowed by the former. Shah Jahan was the greatest patron of Mughal architecture. The astronomical sums that were utilised for expenditure on his tombs, palaces, hunting pavilions, pleasure gardens and entire planned cities, is extraordinary even judging by modern standards! Just as the literary and painted image of Shah Jahan became increasingly ceremonial and formal, so did his architecture. The bulk of Mughal architecture under Shah Jahan was meant to serve as an imperial setting, which had taken on a specific air of formality, unprecedented in earlier Mughal structures. The meticulous utilisation of white marble inlaid with stones, accentuated and marked during the later portion of Jahangir`s reign, characterises much of Shah Jahan`s architectural production. His buildings appear increasingly refined, establishing a style that became an Indian `classic`.

However, Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan, as one perceives in present times would never have materialised to such extents, had it not been for his ambitious and zealous goals to life, which were set during his early years. Under Shah Jahan, Islamic orthodoxy is known to have increased in leaps and bounds, an element which went ahead far to associate itself with architecture during Mughal times of Shah Jahan.. However the seeds of a promising future Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan rested in his capable hands at an early age, when the emperor was still a prince, being patronaged under a proud father, emperor Jahangir.

While a prince, Shah Jahan had erected the Shahi Bagh in Ahmedabad, a building characteristic of Jahangir`s time. After forcing the Udaipur rana to bow to Mughal authority, he had constructed buildings on a hill in Udaipur in 1613. The prince`s dwelling was quite near the summit. Below it the nobles built their own houses - the higher their rank, the closer to the imperial seat. Thus, early in his career, Shah Jahan had revealed an interest in the organisation of an entire imperial retinue. Indeed, if noted within the purview of princely patronaged works, Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan was becoming loftier day by day, that too when the future emperor was just crossing his teens! Near Burhanpur in the Deccan, Shah Jahan had sculpted an exquisite hunting resort on an artificial lake he had created by adding a second dam to one constructed prior to his times. Even earlier, he had commenced construction of the renowned Shalimar Garden in Kashmir. Shah Jahan deeply adored the Shalimar Garden and in 1634, after his coronation, had further embellished the site. Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan was as if a toy in the hands of a boy, excited and anxious to build and rebuild all kinds of Islamic architectural masterpieces, reminiscent of Timurid construction in Persian background.

Shah Jahan had constructed and renovated forts throughout his reign. For instance, he had continued to build at the Agra Fort long after he has shifted his capital to Delhi. However, most of the construction in his Lahore and Agra forts was accomplished in about the first decade of his rule. By contrast, Shah Jahan`s entire Red (Shahjahanabad) Fort was executed after 1639. All three of these major projects bear striking similarities, reflecting continuing Mughal practice. Perhaps the most notable from amongst the cluster of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan was the placement of imperial chambers at the fort`s far end overlooking a river. This practice was established certainly by Akbar`s reign and probably as early as Babur`s. Although the Agra and Lahore forts were constructed at the same time, they each possess individual personalities and are worthy of separate discussion. Shortly after his accession Shah Jahan had ordered thorough renovations at the Agra and Lahore forts, then the two most substantial ones. These are but two instances of Shah Jahan`s continual effort to improve existing fortified palaces. In addition, new buildings were added to Akbar`s and Jahangir`s structures in the Gwalior Fort, but it was little utilised by the king and served primarily, as it had earlier, as a crucial jailhouse. It is known that the Kabul Fort had served as Shah Jahan`s residence during the unsuccessful campaigns to consolidate territory originally part of the Timurid homeland. However farther or to wilderness does it belong, Shah Jahan`s touches to Mughal architecture are still unprecedented, which certainly is not an overstatement, be it in Kabul, or as near as in Old Delhi.

Agra, the city - an epitome of Mughal architectural masterworks since the arrival of Babur, has untiringly assayed crucial and substantial roles in order to bring to life historic creations that one witnesses still in its intact format in present times. However, Agra`s most sublime and irreplaceable replacements of bounteous beauty were achieved during the lifetime of that individual named Shah Jahan. Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan in the Agra city, had achieved its unity in diversity in the magical and almost godly hands of the said Mughal baadshah. As early as 1637 Shah Jahan had expressed dissatisfaction with Agra`s terrain, hence with its suitability as the imperial capital. Nevertheless, he and his favourite daughter, Jahan Ara, had endeavoured to improve the city. Soon after 1637, Shah Jahan had constructed a public arena in the shape of a Baghdadi octagon in front of the fort; its perimeter consisted of small chambers and pillared arcades. At the same time, Jahan Ara had requested permission to endow a Jami mosque close to the Agra fort. Earlier one had been commenced near the river, but its construction was interrupted so that the Taj Mahal could be completed quickly. Some of the land for Jahan Ara`s mosque was crown land, but the rest had to be purchased; in accordance with tradition, it could not be confiscated.

Jahan Ara`s imposing Jami mosque is elevated well above ground level and during Mughal times was visible from a considerable distance. Its large prayer chamber composed principally of red sandstone and white marble trim is surmounted by three domes embellished with narrow rows of red and white stone. The prayer chamber`s east facade is pierced by five entrance arches, the central one within a high pishtaq. It recalls the elevation, although not the ornamentation, of Wazir Khan`s mosque in Lahore, built in 1634. Framing the pishtaq is a rectangular band of black lettering inlaid into the white marble ground, similar to the bands used on the nearby tomb of Mumtaz Mahal. Here the inscriptions are not Quranic but Persian panegyrics, largely praising Shah Jahan and his just rule. It is verily evident that Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan, during his primetime or during his later years, when the architectural wonders would stand upon royal backing for the royal household, had given birth to most unusual of sculptural pieces.

Jahan Ara`s imposing Jami mosque is elevated well above ground level and during Mughal times was visible from a considerable distance. Its large prayer chamber composed principally of red sandstone and white marble trim is surmounted by three domes embellished with narrow rows of red and white stone. The prayer chamber`s east facade is pierced by five entrance arches, the central one within a high pishtaq. It recalls the elevation, although not the ornamentation, of Wazir Khan`s mosque in Lahore, built in 1634. Framing the pishtaq is a rectangular band of black lettering inlaid into the white marble ground, similar to the bands used on the nearby tomb of Mumtaz Mahal. Here the inscriptions are not Quranic but Persian panegyrics, largely praising Shah Jahan and his just rule. It is verily evident that Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan, during his primetime or during his later years, when the architectural wonders would stand upon royal backing for the royal household, had given birth to most unusual of sculptural pieces.

Special and exceptional palaces for hunting and retreat were another striking feature to the gradually growing scale of excellence of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan. Hunting was an illustrious sport, but it was also intended to portray the emperor`s prowess and skill. While hunting could take place anywhere, certain areas renowned for their excellent game were maintained as imperial reserves. At a number of these, Shah Jahan, in order of betterment and to derive more pleasure from such regal pursuits, had erected permanent palaces and pavilions. By far the best preserved and largest is the hunting estate at Bari.

The Bari palace, not far from Babur`s Lotus garden at Dholpur, was accomplished by 1637. Almost every year thereafter Shah Jahan hunted here for several days. Known during Mughal times as the Lai Mahal, or Red Palace, on account of its red stone fabric, the lodge is situated on the edge of a lake. Two small walled enclosures, one of them a hammam, overlook the lake`s north end. A long causeway with chattris links these enclosures with a large pavilion on the lake`s east. This pavilion is further divided into three courtyards with a small char bagh in the middle of each. The side courtyards were utilised by men and women separately. The central one clearly was reserved for imperial use and contained the very components essential to Mughal court ritual. Centrally placed on this courtyard`s east wall is the emperor`s jharoka, or viewing balcony shrouded with a bangala roof. Whatever were the causes, Mughal emperor Shah Jahan indeed was ready with his tools to construct master architectures in almost every feasible places, just as in the Lai Mahal.

Surviving palaces at Rupbas and Mahal, not far from Agra, are considerably smaller than the one at Bari, but follow a similar layout, apparently one characteristic of a hunting lodge. Others however were less elaborate, for example, one at Sheikhupura in Punjab. This was commenced by Jahangir and in 1634 the complex was partially reconstructed by Shah Jahan.

In 1653, Shah Jahan had ordered the construction of a summer palace at Mukhlispur, approximately 120 km north of Delhi on the Yamuna River. The emperor had favoured the palace and its pavilions, renaming it `Faizabad`. There, he had found respite from Delhi`s blistering heat; moreover, towards the end of his reign, the palace served as a refuge when plague and cholera had infested the imperial capital. Although but a shadow of its former magnificence, this summer retreat featured all the chambers necessary for Mughal court ceremony, administration and daily life. A distinct alteration in building art during the Shah Jahan period brought in a natural change in the architectural pattern during Shah Jahan`s regime. Marble, especially of the textural quality generally provides its own decorative looks due to its delicate graining. Its ornamentation requires care, almost sparingly applied; otherwise the surfaces become fretted and perplexed. This technique was well comprehended by Shah Jahan and each of his marble structure from later years too, just like the hunting wonders, bears the testimony of the supremacy of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan`s monumental regime.

A number of Akbar`s sandstone buildings within the Agra Fort were demolished by Shah Jahan to make room for pavilions of a more approved kind. In their place rose most of the buildings such as the Diwani-i-Am, the Khwab Garh, the Shish Mahal, the Musamman Burj and the Naulakha. Earlier Akbar had introduced the marble structures into the sandstone fortresses; however, this architectural scheme was developed further by Shah Jahan and produced several wonderful creations in the Mughal dynasty. Apart from these Islamic architectures, Shah Jahan indeed had constructed umpteen other remarkable constructions, which still stand as the bright illustrations of the colossal development of Mughal architecture during Shah Jahan`s time. All these architectural buildings were the fusion of Indian and Persian culture and have gradually become legendary worldwide.