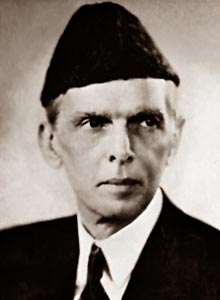

Many Muslims were not enthusiastic about the Nehru report. Among them Mohammed Ali Jinnah was a prominent figure. Jinnah felt that Muslims had sacrificed too much in order to reach a compromise the issue of communal representation. As for example, they had allowed congress to go back on concessions granted by the Lucknow pact of 1916. Jinnah declared himself to be anxious for a harmonious settlement. At an `all-parties` convention held in Calcutta in December, he pleaded for unity. He declared that `we are sons of this land we have to live together`, but at the same time he asked for more safeguards for Muslims. His proposed amendments were rejected and he walked out of the convention.

Many Muslims were not enthusiastic about the Nehru report. Among them Mohammed Ali Jinnah was a prominent figure. Jinnah felt that Muslims had sacrificed too much in order to reach a compromise the issue of communal representation. As for example, they had allowed congress to go back on concessions granted by the Lucknow pact of 1916. Jinnah declared himself to be anxious for a harmonious settlement. At an `all-parties` convention held in Calcutta in December, he pleaded for unity. He declared that `we are sons of this land we have to live together`, but at the same time he asked for more safeguards for Muslims. His proposed amendments were rejected and he walked out of the convention.

Jinnah then allied himself with the less progressive Muslims, on whose behalf he drew up a list of principles. These principles are popularly known as the so-called fourteen points. These fourteen points represented the Muslim`s minimum demands. These included separate elevates, the reservation of one-third of the seats in the legislative assembly for Muslims although the community accounted for only one-quarter of the ration, and the creation of Muslim majority provinces. Later the league formally rejected the Nehru report. A brief period of Hindu Muslim co-operation had come to an end.

This unfortunate development seemed to be offset for a while by change for the better in the attitude of the British. The labour party had promised so much to Indian nationalism. It came to power in the British elections. The viceroy lord Irwin, went to London, and on his return stated that the government accepted that `the natural issue of India`s constitutional progress` was `minion status`. He also announced that a round table conference, to which Indian leaders would invited, would be held to work out a constitution for India.

In England, there was still considerable opposition to Indian aspirations despite the viceroy`s assurances. The labour party did not have a clear majority, and imperialist interests were still powerful. Lord Birkenhead, the former secretary of state, declared `no one had the right to tell the people of India that they were likely to attain dominion status` but hopes were still high in India. It was stated only two months after Irwin`s statement. In the `Delhi manifesto`, Gandhiji, the two Nehru, Tej Bahadur Sapru and others, pledged their co-operation in evolving a dominion constitution. But when Gandhiji, the elder Nehru and others met the viceroy in December, Irwin said that he could not promise that the British government would grant dominion status. This turnabout settled matters for Gandhiji. From this moment he dropped his opposition to complete independence.

In England, there was still considerable opposition to Indian aspirations despite the viceroy`s assurances. The labour party did not have a clear majority, and imperialist interests were still powerful. Lord Birkenhead, the former secretary of state, declared `no one had the right to tell the people of India that they were likely to attain dominion status` but hopes were still high in India. It was stated only two months after Irwin`s statement. In the `Delhi manifesto`, Gandhiji, the two Nehru, Tej Bahadur Sapru and others, pledged their co-operation in evolving a dominion constitution. But when Gandhiji, the elder Nehru and others met the viceroy in December, Irwin said that he could not promise that the British government would grant dominion status. This turnabout settled matters for Gandhiji. From this moment he dropped his opposition to complete independence.