Introduction

Food in the Mauryan period largely comprised the dietary practices and beverages consumed between 300 BC and 75 AD. These aspects have been extensively documented in sources such as the Arthashastra, the rock edicts of Ashoka, and the accounts of Greek historians.

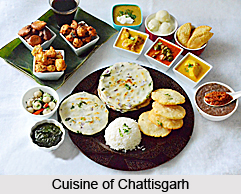

Food in Mauryan Period largely depended on two seasons. While the winter season included rice and millet which formed a major part of the Maurya Empire, the summer season included wheat and barley. Along with this, Kautilya mentions that there was a third crop that was cultivated between these two seasons. This included "Munga" and "Masa". With new crops it added to the stock of crops grown in Indian agriculture along with new food items. Overall this period too followed the same style of food habits which included cereals, pulses, dairy products, meat and beverages.

Food Production During Mauryan Period

Food in Mauryan Period differed from its predecessors in a very limited way when it introduced some more types of cereals which were popularly cultivated in ancient Mauryan Empire. In case of Rice, along with the old varieties of rice namely Vrihi, Sali, Kodrava and Priyamgu, two new varieties of rice namely "Draka" and "Varaka" was introduced. Similarly, two kinds of Barley were also introduced among which one was cultivated while the other was not cultivated but commonly used in preparing a mess, a gruel, groats and cakes. While Gruel was prepared with inferior food grains; Groats were eaten with curds. Wheat occupied a more vital place among the cereals than in the previous period, it being invariably mentioned with barley. Besides the old pulses, pea was indeed popular. Soup was indeed popular and known as Patanjali.

Apart from producing grain, people during Mauryan Period

also engaged in trading of goods to overseas countries, especially Greece. The

practice of trading was not just beneficial for the economy but also impacted

the food habit of the people. Different cultures were blended to create a

unique kind of cuisine under Mauryan rule that never existed before.

Food in Mauryan Period further included large variety of dairy products.

Besides cow’s milk, milk of buffaloes, sheep and goat was also used. The Mauryan

Empire was equally habituated in taking meat products as Arthashastra lays

down specific role of the Superintendent of Slaughter Houses. Along with meat,

fresh fishes were taken as well as sweet during

Maurya Empire included honey and product of Sugarcane such

as juice of sugarcane, guda, raw sugar, sugar-candy and refined sugar which

were amiably popular.

Food in Mauryan Period was largely prepared with salt and spices that

include normal salt, rock salt, sea salt, bida salt and nitre, along with the

spices like long-pepper, ginger,

cumin seeds,

white mustard and corianders, cloves and turmeric.

This further included 4 types of cardamom which

are white, reddish white, short and black which was produced in India during

that time.

Administrative Control Over Food Produce

Various apex positions were created by the empire to control food produce and its marketing to benefit the people.

Superintendent of Agriculture: The Superintendent of Agriculture under the Mauryan Empire, well versed in the science of agriculture and supported by others trained in the discipline, carried out a wide range of responsibilities. He was required to possess detailed knowledge of meteorological conditions, including the amount of rainfall and its seasonal distribution across different regions. Based on this understanding, he supervised the sowing of seeds in various types of soil and at appropriate seasons, taking into account both rainfall patterns and the nature of the crops.

Superintendent of Commerce: The king was expected to promote commerce by providing necessary facilities, constructing roads for both land and water transport, and establishing market towns. The Superintendent of Commerce was responsible for assessing the demand or lack of demand for various goods, as well as monitoring fluctuations in their prices. He also determined the appropriate timing for the distribution, centralization, purchase, and sale of different commodities. Additionally, it was his duty to ensure that sellers did not earn excessive profits that could be detrimental to the welfare of the people. The Superintendent of Commerce also supervised the weights and measures used by traders and exercised control over prices. Only authorized persons were permitted to collect grains and other merchandise.

Superintendent of Cows: There was a Superintendent of Cows entrusted with a wide range of responsibilities, including the classification of cattle. He maintained detailed registers of different classes of herds and supervised the work of cowherds. The Superintendent ensured that cows were milked strictly according to prescribed rules and monitored the use of milk as well as the quantity of butter obtained from milk cows, buffaloes, goats, and sheep in relation to the fodder provided. Rations were fixed for different types of bulls and cows, and all cattle were supplied with ample fodder and water. Draught oxen and milk-yielding cows were provided subsistence in proportion to the duration of their service. Cattle owners were required to protect their animals from dangers such as drowning, lightning, tigers, and cobras. They were also expected to apply appropriate remedies to calves, aged cattle, and animals suffering from illness.

Superintendent of Slaughter Houses: The appointment of a Superintendent of Slaughter Houses reflected a high point in public health legislation and administrative control in ancient India. This office shows the state’s concern with regulating slaughter and safeguarding broader public welfare. Several animals, including horses, bulls, monkeys, deer, fish in lakes, and game birds were placed under state protection, indicating a structured approach to the conservation and management of natural resources. Entry into designated forest preserves was strictly prohibited, reinforcing the state’s authority over wildlife and forested regions.

Superintendent of Liquor: The Superintendent of

Liquor was responsible for overseeing and regulating the manufacture and sale

of different kinds of alcoholic beverages. Detailed regulations governed the

varieties of drinks, their methods of preparation, and the rules under which they

could be sold. These provisions reflected the careful oversight and vigilance

exercised by the lawgivers of the period. During occasions such as festivals,

fairs, and pilgrimages, the right to manufacture liquor was permitted only for

a limited duration of four days. This restriction demonstrated a balanced

effort to accommodate social customs while maintaining strict administrative

control.

Standard Diet During Mauryan Period

Kautilya provided a detailed list of food articles that served as an index of both the diversity and sufficiency of provisions available at the time. These included grams, oils such as clarified butter, granulated sugar, sugar-candy, honey collected from bees, grape juice, and various kinds of salts derived from both mines and the sea. The list further encompassed fruits, vegetables, fish, and spices, reflecting the wide range of foodstuffs in regular use.

The text also outlined the different practices employed in the preparation of food for daily consumption. Rice was pounded, pulses were split, and grains and beans were fried. Flour production was carried out by specially trained workers, while oil extraction was entrusted to shepherds and professional oil makers.

Rice as staple: Rice was likely the staple article of diet, although other grains substituted for it under varying circumstances and in different regions. It is noteworthy that the Mauryan Empire maintained fixed and regular rations not only for rice but also for other food articles. Administrative codes clearly prescribed the specific quantities of rice allotted or permitted for each individual, including men, women, and children, reflecting a regulated and systematic approach to food distribution.

Standard Meal: According to pre-decided dietary norms, one prastha of pure, unsplit rice, one-fourth prastha of supa, and clarified butter or oil equal to one-fourth of the supa were considered sufficient to constitute a single meal for an Arya. For a man of the lower caste (avara), one-sixth prastha of supa along with half of the aforementioned quantity of oil was deemed adequate for one meal.

The same rations, reduced by one-fourth of the stated quantities, were prescribed for women, while children were allotted half of the rations specified for adults.

Detailed guidelines were also laid down for the preparation

of meat. To dress twenty palas of flesh, half a kudumba of oil, one pala of

salt, one pala of sugar (kṣara), two dharaṇas of pungent substances (kaṭuka, or

spices), and half a prastha of curd were required. When larger quantities of

meat were prepared, these ingredients were to be increased proportionately. In

the case of cooking sakas, including dried fish and vegetables, the same

ingredients were to be added in quantities one and a half times greater.

Beverages During Mauryan Period

Along with other fruits, and beverages during Maurya Empire were available in a great variety including different types of intoxicating liquors. Kautilya lays down the responsibility of the Superintendent of Liquor which shows the popularity of the liquor in Maurya Empire. Along with this, Megasthenes mentions that Indians used to take liquor during the festivals. Among the common drinks were various forms of wines and rice beers. Apart from liquors, beverages in common use incuded butter milk, grape juice, fruit juices and syrups that was consumed extensively in the Maurya Empire.

Cooking Methods in Mauryan Period

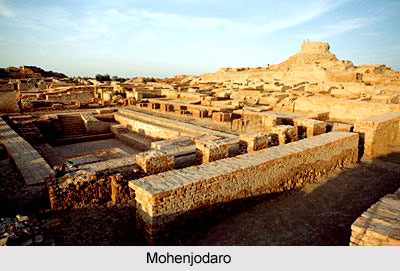

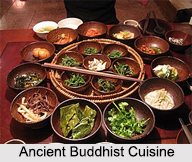

The Mauryan period, often regarded as the golden age of

India, witnessed the development of advanced cooking methods. Archaeological

evidence, including pots and pans recovered from this era, indicates a high

level of skill and precision in the crafting of clay utensils, which were

widely used in everyday domestic life. Religious influences such as Buddhism

and Jainism, and later Islam, played a significant role in shaping the food

habits of the people. The rock edicts of Ashoka, in particular, advocated the

benefits of vegetarianism, although they made no reference to the utensils used

in food preparation. While cuisine varied across regions, it was generally

rich, aromatic, and spicy. Common cooking vessels such as the degh or degchi

and the handi were widely used, especially in the preparation of traditional

North Indian dishes.