Buddhist influence on Post Gupta Period Temples is the monumental works of art that conceives the very bases of religiosity, the one of Buddhism that had been spread during the genre.

Buddhist influence on Post Gupta Period Temples is the monumental works of art that conceives the very bases of religiosity, the one of Buddhism that had been spread during the genre.

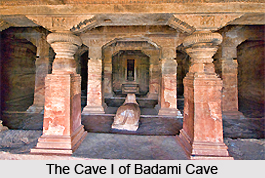

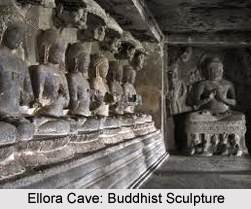

The Buddhist caves in Ellora were in all probability not begun until work on the earlier Hindu shrine had terminated. They belong to the later Mahayana (Great Vehicle) phase. Though Caves 2 and 3, for instance, correspond to the more intricate of the Ajanta caves more than a century earlier, not only did the plans soon become far more perplexed, but a whole new iconography had emerged, born of unfathomed changes in philosophy, liturgy and common viewpoint. The stupa all but disappeared. The stock of icon-types at Ajanta was minutely bigger than in Kushana times, but now several new Bodhisattvas appear- as well- for the first time- as female goddesses or Bodhisattvas for example Tara, together with four-armed images, definitely borrowed from Hinduism and so-called speeches of Avalokiteshwara, with the great Bodhisattva depicted as Lord of Travellers flanked by scenes of wayfarers in suffering. A present day text portrays to what degree the enormous Bodhisattvas were invoked and worshipped.

The purpose of these rock-cut halls is already under alteration. Cave 2 could not have been a vihara, because there are barely any cells. Expansions on the evolved Ajanta design are introduced, like the colonnaded gallery on both sides of the hall, behind which are rows of Buddhas seated in pralambapada. Buddhas and worshippers now also line the walls of the sanctum itself. Capitals differ from the vase and foliation kind (Cave 3) to chamfered cushions. The sculpture, lacking the earlier profusion of detail, consists of conventionalised interwoven forms, prone to exaggeration, as in the case of gigantic beasts. The faces incline to be over-simplified.

Some caves are bigger and more elaborate compared to any Buddhist excavation so far attempted. Cave 5 portrays a wholly fresh type, in that it expands into the rock to a much superior length than its width and yet is not a chaitya hall. It is rectangular, with two rows of ten pillars in the centre and between them two rows of incessant elevated stone benches. It is however not known what functions this use to serve. It has been recommended that they were used as dining hall benches or tables (there are also 17 cells and a shrine), but it is more probable that the monks sat there in assembly or for teaching, as must have been the function of the seats around the tiled patio at Harwan. There is a similar inexplicable characteristic in one of the caves at Bagh.

Enormous standing Bodhisattvas, with attendee figurines, stand as dvarapalas on both sides of the sanctuary of quite a few of the caves, an aspect evidently borrowed from the Hindu cave. In Cave 6 these are principally delicate, with their increasing vivacity, wonderfully created muktas, and attendees in distinctive Gupta postures. The individuality of some of the Bodhisattvas is baffling. Those with a tiny Buddha in their on are surely acknowledged as Avalokiteshwara and recurrently have a deer-skin (ajina) over their shoulders. Those with a stupa in their headgear are generally thought to represent Maitreya, but the attendee figurine of the Maitreya in Cave 6 wears a vajra in his headgear. On the right wall of the vestibule is Mahamayiri, and opposite her, Tara, also seated, with a stupa in her jalamukha and donning an ajina. Cave 8 is remarkably alike in design to a Hindu shrine, and contains what is presumably the earliest multi-armed Buddhist statuette, the Avalokiteshwara beside the seated Buddha in the sanctum.

Cave 10, the so-called Visvakarma, is the only chaitya hall in Ellora and the last of this category of cave to be excavated. The chaitya hall had been made archaic by three progresses- the supplanting of the stupa as the chief cult entity, the enshrinement of Buddha images in the viharas, and possibly, as it is noticed, their use as places of assembly or `combination` halls, similar to Cave 5. What is more, the immense three-storeyed caves like the Tin that, with their colossal halls, now catering to the monks` requirements for splendour as well as or better than chaitya halls. The Vishwakarma portrays the metamorphosis roughly beyond identification of a type of rock-cut building, going back to 2nd century H.C. It is apsidal-ended. The row of interior columns and the high-carved clerestory diverge slightly from those of Caves 19 and 26 at Ajanta, but the stupa is all but obliterated by the enormous figure of a seated Buddha. Entryway is now by a doorway in a screen wall into a courtyard with two-storey verandas on both sides, with cells behind them. Most outstanding is what has come about of the facade itself, the most prominent and distinctive aspect of a chaitya hall. A colonnaded entryway porch defends an extensive terrace behind which rises a poised composition of a chaitya window, flanked by two huge recesses, surmounted by udgamas of already complex form, with split and overlying gavakas. The shapes of these features recommend a date, approximately 650 A.D., the udgama (pediment) emerging as one of the prominent features of post-Gupta architecture. The window still serves the function of the novel chaitya archway, to let in light to the interior, but its shapes have become wholly ornamented, assuming no relation to the barrel-vault inside. Inside, equivalent to the terrace is a gallery in the arrangement of a European minstrels` gallery. The intention, however, is not known.

Cave 10, the so-called Visvakarma, is the only chaitya hall in Ellora and the last of this category of cave to be excavated. The chaitya hall had been made archaic by three progresses- the supplanting of the stupa as the chief cult entity, the enshrinement of Buddha images in the viharas, and possibly, as it is noticed, their use as places of assembly or `combination` halls, similar to Cave 5. What is more, the immense three-storeyed caves like the Tin that, with their colossal halls, now catering to the monks` requirements for splendour as well as or better than chaitya halls. The Vishwakarma portrays the metamorphosis roughly beyond identification of a type of rock-cut building, going back to 2nd century H.C. It is apsidal-ended. The row of interior columns and the high-carved clerestory diverge slightly from those of Caves 19 and 26 at Ajanta, but the stupa is all but obliterated by the enormous figure of a seated Buddha. Entryway is now by a doorway in a screen wall into a courtyard with two-storey verandas on both sides, with cells behind them. Most outstanding is what has come about of the facade itself, the most prominent and distinctive aspect of a chaitya hall. A colonnaded entryway porch defends an extensive terrace behind which rises a poised composition of a chaitya window, flanked by two huge recesses, surmounted by udgamas of already complex form, with split and overlying gavakas. The shapes of these features recommend a date, approximately 650 A.D., the udgama (pediment) emerging as one of the prominent features of post-Gupta architecture. The window still serves the function of the novel chaitya archway, to let in light to the interior, but its shapes have become wholly ornamented, assuming no relation to the barrel-vault inside. Inside, equivalent to the terrace is a gallery in the arrangement of a European minstrels` gallery. The intention, however, is not known.

Caves II, 12 and 15 are all multi-storeyed, the first two are three-floored and Buddhist, the last, with only a ground floor and the first storey, Hindu. Cave II, nevertheless, houses two or three images, and Cave 15 possesses some cells, representing that it had been designed to be Buddhist, though the nrtya mandapa (dance pavilion) in the courtyard is tricky to harmonise with this. Caves I and 12, because of their highly improved iconography and aspects of their sculptural works, are surely the last Buddhist caves in Ellora.

Similar to Cave 10, Cave Do Thal has a huge open courtyard in front. Its images comprise, for the first time, such statuettes like Sthiraketu, with a sword, and Nanaketu, holding a flag and Manjushri, carrying a lotus, on which rests a book, hereafter his most characteristic iconographic attribute. Architecturally, it is a less ornamented and less ruthless edition of the great Tin Thal (Cave 12). Here, like the Vishwakarma, the outsized forecourt is entered by doors in a screen wall. The frontage is entirely plain, like in the Do Thal, emitting no suggestion of the brilliance within or the size of the three immense superimposed halls. On the ground floor is a six column antechamber in front of the chief shrine, which has the now-normal display of guardians on the side and back walls; however, all are seated in padmasana, even the Bodhisattavs Manjushri and Maitreya, acting as doormen, one on both sides of the entryway. Above the four Bodhisattvas on each side-wall of the shrine are five Dhyani Buddhas. Tara and Cunda face the Buddha inside. The goddesses wear kucabandhas (breast bands), and some of the figurines have kirttimukha (lion-mask) armlets with late features, as are the shapes of certain mukutas. There is also a pair of doormen with their arms crossed and leaning on clubs, in the southern style.

The first storey is exceptional in possessing cells on all four sides of the colonnaded hall. This is accomplished by placing the side entranceways from the veranda at the utmost ends of the frontage, which, given the extraordinary size of the hall, permits three inward-facing cells on both sides of the central entryway. The second storey is an enormous oblique hall with five rows of eight columns and Buddha`s on the sidewalls at the end of each slanting aisle. In the centre of the back wall, an antechamber with two columns leads to the shrine. On both sides of the antechamber, satisfying each wall space, are seven seated Buddhas- on the left, the Manusi Buddhas, each acknowledged by the singular Bodhi Tree under which he had gained Enlightenment, on the right, seven Dhyani Buddhas, their hands in dharmachakra mudra and seated under sunshades. On each side of the antechamber and alongside the shrine door, comes six seated goddesses of which, some have been provisionally distinguished. They include- Vajradhatvisvari, Khadiravarti, Cunda, Janguli, Tara, Mahamayiiri, Bhrkuti, and Pandara. Inside the sidewalls of the shrine are eight standing Bodhisattvas, carrying chowries in one hand. By the symbols in there other hands, Maitreya (water pot), Sthiracakra (sword), Maiijusri (book on lotus), and Jnanaketu (banner) can be distinguished. Thus all the walls of the upper level, including the inside of the shrine, are lined with statuettes. Repeated numerous times inside the cave is a square, divided into nine compartments, eight with Bodhisattvas, a Buddha in the centre- possibly the earliest surviving mandalas.

Cave 15 (the Dasavatara) is undeniably late in its built. With its upper storey, it tallies with Buddhist caves, like Nos. 12 and 13 (some cells recommend that it was begun as a Buddhist cave). A very deep court is also a late attribute. What is more, the huge, monolithic, but quite a divided mandapa in the court has exterior recesses, topped with an udgama, ornamented with a mesh or honeycomb of gavasaks, a distinguishing feature of post-Gupta free-standing temple architecture. It is dubious whether this aspect used to happen anywhere before the middle or late 7th century. The Dasavatara is the only monument in Ellora with a former inscription of any historical grandness. It registers that either the Rashtrukuta Dantidurga (c. 730-55) or a contemporary mogul had visited the temple, plausibly towards the end of Dantidurga`s reign, when it appears to have been in the completions- indeed, it may have been so for some years or even decades. What is certain is that a fresh liveliness invigorates the sculpture. The old Kalachuri compositions, huge and thronged with figurines, have been substituted by new, commonly simpler and more vibrant ones, often indistinguishable to some in the adjacent Kailasa (Temple 16), an unchallenged Rashtrakuta foundation. Arm bands are no longer spirals, as in Kalachuri sculpture, or of pearls, as worn by many Gupta and post-Gupta figurines, but kirttimukhas, an 8th century innovation from further south. Statuettes shoot supplementary arms, and their postures are more vivacious, when not simply theatrical in an unsuccessful endeavour to repair for the limitation in composition. Typical is the Narasimha with, standing beside him, a Hirarnyakasipu of equivalent size, his head thrown back and sidewise in a malformed Rashtrakuta posture.

Cave 15 (the Dasavatara) is undeniably late in its built. With its upper storey, it tallies with Buddhist caves, like Nos. 12 and 13 (some cells recommend that it was begun as a Buddhist cave). A very deep court is also a late attribute. What is more, the huge, monolithic, but quite a divided mandapa in the court has exterior recesses, topped with an udgama, ornamented with a mesh or honeycomb of gavasaks, a distinguishing feature of post-Gupta free-standing temple architecture. It is dubious whether this aspect used to happen anywhere before the middle or late 7th century. The Dasavatara is the only monument in Ellora with a former inscription of any historical grandness. It registers that either the Rashtrukuta Dantidurga (c. 730-55) or a contemporary mogul had visited the temple, plausibly towards the end of Dantidurga`s reign, when it appears to have been in the completions- indeed, it may have been so for some years or even decades. What is certain is that a fresh liveliness invigorates the sculpture. The old Kalachuri compositions, huge and thronged with figurines, have been substituted by new, commonly simpler and more vibrant ones, often indistinguishable to some in the adjacent Kailasa (Temple 16), an unchallenged Rashtrakuta foundation. Arm bands are no longer spirals, as in Kalachuri sculpture, or of pearls, as worn by many Gupta and post-Gupta figurines, but kirttimukhas, an 8th century innovation from further south. Statuettes shoot supplementary arms, and their postures are more vivacious, when not simply theatrical in an unsuccessful endeavour to repair for the limitation in composition. Typical is the Narasimha with, standing beside him, a Hirarnyakasipu of equivalent size, his head thrown back and sidewise in a malformed Rashtrakuta posture.

The great Kailasa Temple (No. 16) in Ellora, together with three other, much lesser shrines, is of an altogether dissimilar type- a monolithic reproduction of a structural temple. These, however, represent the northernmost instances of the unfeigned Dravida style, and their sculpture manifests that of areas further south in the Deccan, instead of Maharashtra and Konkan. There are rock-cut reproductions of northern-type temples at Dhammar in Madhya Pradesh and in Masrur in Kangra.