Performance of Dhrupad takes place in two steps. The first step is Alaap (the prelude) and the second step is the singing of the Dhrupad or the actual composition. The Alaap comes before the composition. The only exception to this is Haveli Dhrupad where the Alaap is sung also in the middle of the composition as in Khayal. In Dhrupad the Alaap is very elaborate and presents all the identifying features of the Raaga. In contrast to this in Khayal, Thumri, Tappa etc. the Alaap is very short at this stage. In Haveli Dhrupad the Alaap is abridged and is sometimes presented only in Droha (ascent) and Avaroha (descent) but despite its abridged form, the Alaap even here presents the identifying features of the Raaga.

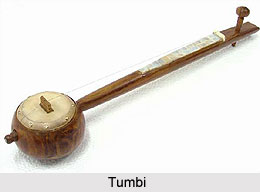

During the Alaap only the Tambura is used as an accompaniment. The drum remains silent save for an occasional stroke to show the change of Laya. The singer demonstrates the important note or notes of the Raaga as well as the insignificant ones by means of Bahutva and Alpatva. He also demonstrates Vaat Svara (the predominant note), Samvadi Svara (the consonant note), Anuvadi (the dependent notes), Vivadi (the dissonant), Durbala Svara (the weak note or notes), Visranti Svara (the note or notes on which the musical phrases are being ended), Uthana and Calana (the manner of deployment of notes). He also demonstrates the relative importance of Purvanga (the notes of the lower register and the lower part of the middle register) and Uttaranga (the notes of upper part of the middle register and the upper register). The Alaap has no text and usually syllables like ta nom na re de ri etc. are employed. These syllables are collectively called nom tom. Some musicologists are of the view that in earlier times it was customary to sing Alaap with phrases like Om ananta Narayana Hari or Tun hi ananta Hari as a kind of invocation of God. Later on these phrases disappeared but left nom tom as a vestige. The Alaap is performed in four steps. In the first step the notes of lower register are sung and in later steps the notes of progressively higher registers are sung. At the end of these four steps the phrases of nom tom like ne tano or tana to om are sung. The end of each step is indicated by a stroke of the drum.

After the Alaap comes the Dhrupad or the song-text, also called Bandish. The three components of this section are song-text, melody and rhythm, all of which are evenly accentuated. Rhythmic accompaniment is provided by a two-headed barrel-shaped drum called Chautaal. The ten-beat sool taal and the dhammar taal of 14 beats are also used often. There are a total of four sections in the dhrupad- Sthayi, Antara, Sanchari and Abhog.

The first section which is sung is the Sthayi (meaning steady). The weight of the Raaga and of the composition falls on this section. The first phrase of the Bandish, which carries the characteristic melodic intonation and weight of the Raaga, is sung first. The Pakhavaj player joins the singer at count one of the Tala cycle, providing accompaniment with beats from this point on, thus setting into motion the rhythmic cycle. While delivering the Sthayi, the singer is free to pick the speed he wishes to. In the Sthayi section only the lower tetra-chord (Poorvanga) of the Raaga is stressed.

Following a series of improvisations, in the Sthayi section, the singer moves on to the Antara (intermediate) section. It is marked by his transition from the lower octave to the middle and high octaves - i.e., from ma or pa, to taar sa. Further improvisations take place in these two octaves, after which the singer returns to the Sthayi, to attempt improvised variations in a rhythmically oriented manner.

For this purpose, the words of the composition are broken and sub-divided rhythmically into their basic syllabic units and then re-organised, in order to create brilliant syllable-beat and word-beat synchronic patterns. This part is known as Bolbaant (word-divisions). Using the Sthayi, the singer attempts to sing the words in a different tempo, known as Dugun (twice), Trigun (thrice) and Chaugun (quadruple). The tempo would be in multiples of the basic tempo, set by the singer. After this synchronisation with the percussionist for a while, the singer slows down the tempo severely, returns to the first line of the Sthayi and concludes the recital.