About Hindi Literature

The emergence of Hindi literature can be traced back to as early as the 7th or 8th centuries. The dialect that has been chosen as the official language of India comprises of the Khari boli (Modern Standard Hindi) in the Devanagari script. Other dialects of Hindi include: Brajbhasa, Bundeli, Awadhi, Marwari, Maithili and Bhojpuri. The true aura of the Hindi literature was first appropriated in its poetry form and was essentially oral. The earliest works were composed for the purpose of singing or reciting and were thus transmitted for many generations, prior penning them down. Prose was a much later introduction to the Hindi literary scene. The first work of prose in Hindi is generally agreed upon as being the fantasy novel Chandrakanta by Devaki Nandan Khatri.

The emergence of Hindi literature can be traced back to as early as the 7th or 8th centuries. The dialect that has been chosen as the official language of India comprises of the Khari boli (Modern Standard Hindi) in the Devanagari script. Other dialects of Hindi include: Brajbhasa, Bundeli, Awadhi, Marwari, Maithili and Bhojpuri. The true aura of the Hindi literature was first appropriated in its poetry form and was essentially oral. The earliest works were composed for the purpose of singing or reciting and were thus transmitted for many generations, prior penning them down. Prose was a much later introduction to the Hindi literary scene. The first work of prose in Hindi is generally agreed upon as being the fantasy novel Chandrakanta by Devaki Nandan Khatri.

The historical evolvement of Hindi literature as a whole however can be divided into four stages, consisting of: Adi kal (the Early Period), Bhakti kal (the Devotional Period), Riti kal (the Scholastic Period) and, Adhunik kal (the Modern Period). Hindi literature however can also be broadly categorised into four distinguishing forms or styles, represented by Bhakti (devotional - with authors like Kabir, Raskhan); Shringar (beauty - with authors like Keshav, Bihari); Veer-Gatha (glorifying dauntless warriors); and Adhunik (modern).

Adi kal in Hindi literature began from the middle of the 10th century and made its curtain call in the beginning of the 14th century The Adi Kal or the early period in Hindi literature greatly matured in the states of Ajmer, Delhi , Kannauj and extended up to central India in present day modern Madhya Pradesh.

The medieval Hindi literature and its sufficient maturation were marked by the influence of Bhakti Movement and compilation of lengthy, epic poems. This has been marked as the Bhakti Kal or the Devotional Period in Hindi literature. The Bhakti kal or devotional period in Hindi literature also was accentuated by great theoretical development in poetry forms, predominantly from a blend of older forms of poetry in Sanskrit School and the Persian School. These included Verse Patterns like Doha (two-liners), Sortha, Chaupaya (four-liners), etc. This was also the epoch when Poetry was differentiated under the various Rasas. Right after the Bhakti kal it was the influence of the Riti kal in Hindi literature which made the literature further rich. The Riti kal or the scholastic period in Hindi literature spans the period beginning from 1600 A.D. and culminating in 1850 A.D.

Adhunik kal or the Modern Period in Hindi literature commenced in the middle of the 19th century. The most decisive evolution of this period was the germination of Khari boli prose and abundant use of this standard Hindi dialect in poetry instead of Braj bhasha. Modern Hindi literature has been divided into four phases, comprising: the age of Bharatendu or the Renaissance (1868-1893), Dwivedi Yug (1893-1918), Chhayavada Yug (1918-1937) and the Contemporary Period (1937 onwards).

Hindi Literature in Pre-Independent India

Hindi-Literature in Pre-Independence India produced some rather important documents that articulated writers` active political involvement at a time of rising Indian nationalism against British colonialism. The works exhibit a unification of culture and politics, in which culture became the basis on which was waged the complex struggle for India`s freedom. Writers began to carve out an imagined Indian identity, visualizing a nation free of foreign domination and one in which democracy and brotherhood would prevail. Their search manifested itself in numerous ways: patriotic stories that idealized and glorified India`s past, stories urging Hindu-Muslim unity, and stories that exposed and recognized problems relating, among other things, to the exploitation and abuse of peasants, labor, and other marginalized classes under colonial rule. Hindi literature in pre-Independent India thus evidenced all these various factors.

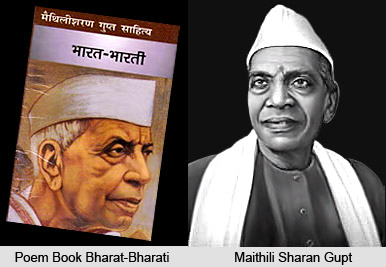

The earliest Hindi language literary works in this stream were seen as early as 1912 in Maithili Sharan Gupt`s (1886-1964) poem "Bharat Bharati" ("The Voice of India," 1912). Gupta`s poem contains songs that glorify India`s past, condemn contemporary socio-political conditions, and suggest a way to a better future on the basis of Hindu-Muslim amity. Emphasis on Hindu-Muslim unity through literature came in the wake of rising Hindu-Muslim animosities around the turn of the century.

The earliest Hindi language literary works in this stream were seen as early as 1912 in Maithili Sharan Gupt`s (1886-1964) poem "Bharat Bharati" ("The Voice of India," 1912). Gupta`s poem contains songs that glorify India`s past, condemn contemporary socio-political conditions, and suggest a way to a better future on the basis of Hindu-Muslim amity. Emphasis on Hindu-Muslim unity through literature came in the wake of rising Hindu-Muslim animosities around the turn of the century.

The communal divide had been set in motion in the nineteenth century, in part, by the debate over the status of Hindi and Urdu as two separate languages. J. B. Gilchrist initiated this separation in the middle of the nineteenth century when he engaged a group of writers at the Fort William College at Kolkata to write Hindustani prose. Hindustani prose was channeled into two distinct styles. One included Hindi without the use of Persianized words, and the other style involved the use of an Urdu that remained as close as possible to Persian. Such conscious segregation of the two languages made the differences between Urdu and Hindi sharper and became a strong basis for communal divisions between Hindus and Muslims during the nineteenth and twentieth centuries.

As Hindu and Muslim nationalists sought mass support from their respective communities through the propagation of the two languages, the debate intensified. The Hindu leadership stressed the need for popularizing Hindi to serve as a link for interregional communication and rally mass support against imperialism. Efforts to propagate the idea of Hindi as the national language were soon undertaken by organizations such as the Brahmo Samaj and the Arya Samaj, which actively promoted Hindi in North India. Pro-Hindi activism also constituted the introduction of Hindi newspapers in Bengal in the nineteenth century and the introduction of Hindi in law courts and schools in Bihar around 1900 (Das Gupta 1970, 83). Within the Hindi area, many organizations devoted to the cause of Hindi were formed. Of these, the Nagari Prachar Sabha in Varanasi in 1893 and the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan, founded in Allahabad in 1910, became the most significant organizations for propagating the use of Hindi. These organizations promoted the Devanagari script and advocated a style that incorporated Sanskrit vocabulary while consciously removing Persian and Arabic words. Mahavir Prasad Dvivedi, the chief proponent of Hindi poetry at the turn of the century and editor of Saraswati, encouraged the use of Sanskrit meters in poetry. His own efforts to propagate this style included invitations to poets to write verse in Hindi, which he corrected before publishing in the journal, and he encouraged young poets to imitate his own lyrics published in Saraswati. With the publication of this new style of verse in Saraswati between 1909 and 1910 by scholars such as Kamta Prasad Guru (1875-1947), author of the first authoritative Hindi grammar, and Ram Chandra Shukla (1884-1941), professor of Hindi in Varanasi and historian of Hindi literature, Hindi poetry received further impetus.

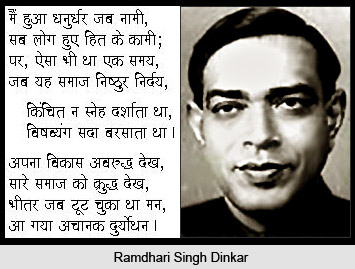

Emphasis on the revival of a Sanskritized Hindi from the orthodox section of the Hindi revivalists led to the development of a highly literate Hindi at the turn of the century and gave a setback to Khadi boli, Braj Bhasha, and Awadhi dialects of Hindustani. Before the language controversy arose, these forms of Hindi or Hindustani were used by Hindus and Muslims alike. For example, Tulsidas`s works Ramcharit Manas and Kavitavali were composed in Awadhi language and Braj Bhasha, respectively. However, after the espousal of Hindi, which initiated the purging of Perso-Arabic words from the language, Braj Bhasha was considered unsuitable for poetry. A revised form of Khadi boli that used Sanskrit instead of Persian vocabulary was employed for Hindi verse. Ayodhya Singh Hariaudh, at this time, wrote his epic poems Priyapravas and Vaidei Banvas in a Hindi that was highly Sanskritized. Others, such as Ramdhari Singh Dinkar and Shyam Narayan Pandey also utilized Sanskrit meters as opposed to the dohas, padas, and kavittas (poetic forms) of medieval poetry.

Emphasis on the revival of a Sanskritized Hindi from the orthodox section of the Hindi revivalists led to the development of a highly literate Hindi at the turn of the century and gave a setback to Khadi boli, Braj Bhasha, and Awadhi dialects of Hindustani. Before the language controversy arose, these forms of Hindi or Hindustani were used by Hindus and Muslims alike. For example, Tulsidas`s works Ramcharit Manas and Kavitavali were composed in Awadhi language and Braj Bhasha, respectively. However, after the espousal of Hindi, which initiated the purging of Perso-Arabic words from the language, Braj Bhasha was considered unsuitable for poetry. A revised form of Khadi boli that used Sanskrit instead of Persian vocabulary was employed for Hindi verse. Ayodhya Singh Hariaudh, at this time, wrote his epic poems Priyapravas and Vaidei Banvas in a Hindi that was highly Sanskritized. Others, such as Ramdhari Singh Dinkar and Shyam Narayan Pandey also utilized Sanskrit meters as opposed to the dohas, padas, and kavittas (poetic forms) of medieval poetry.

Thus, by the first decade of the twentieth century, the language politics motivated by nationalist sympathies largely changed the character of Hindi literature from Hindustani, the standard language, to a highly literate and Sanskritized Hindi. During this period, Hindi received further impetus through Saraswati, edited by Shyamsunder Das, which became the most influential literary journal in the first two decades of the twentieth century. Writings in Hindi were encouraged through competitions for which prizes were awarded. By 1916, the number of journals in Hindi in the Uttar Pradesh region had far surpassed the number in Urdu.

Accompanying this change from Hindustani to a literate Hindi was a celebration of the past glory of India, as well as a privileging of Hinduism. Hindu intellectuals who advocated Hindi and believed in the glorious Hindu past argued that only the reform of Hindu society on the basis of tyag (asceticism) and patriotism could bring about self-government. The revival of a Hindu past was linked to the idea of the vedic "golden age," an idea that had acquired prominence in the late nineteenth century in Bengal as a way of countering British colonialism and had manifested itself in the writings of renowned novelists such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Evoking images of a "golden Hindu age" was the writers` way of resisting the colonial threat and reminding themselves and their readers of the need to recover what India had lost to its colonisers. Soon it manifested itself in Hindi literature as well. While preaching the ultimate unity of all religions, intellectuals and proponents of Hindi insisted on the superiority of Hinduism and refused any compromise with Muslims or Christians. Self-government, or swaraj, meant the rule of a Hindu majority. Hence, a body of literature poured forth evoking the myth of a glorious Indian past dominated by Hindu kings and philosophers, and a Hindu identity was represented as an "Indian" identity. For example, Shyam Narayan Pandey`s epics Haldighati and Jauhar depicted the heroism of Rajputs in resisting the invasions of the Turks and the Mughals. Stories of the greatness of Hindu gods were evoked through mythological tales from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Similarly, in Bhagavad Purana, Makhan Lal Chaturvedi attempted to reawaken a similar sense of duty in the Indian public as the characters in the Bhagavad Gita possessed.

Accompanying this change from Hindustani to a literate Hindi was a celebration of the past glory of India, as well as a privileging of Hinduism. Hindu intellectuals who advocated Hindi and believed in the glorious Hindu past argued that only the reform of Hindu society on the basis of tyag (asceticism) and patriotism could bring about self-government. The revival of a Hindu past was linked to the idea of the vedic "golden age," an idea that had acquired prominence in the late nineteenth century in Bengal as a way of countering British colonialism and had manifested itself in the writings of renowned novelists such as Bankim Chandra Chatterjee. Evoking images of a "golden Hindu age" was the writers` way of resisting the colonial threat and reminding themselves and their readers of the need to recover what India had lost to its colonisers. Soon it manifested itself in Hindi literature as well. While preaching the ultimate unity of all religions, intellectuals and proponents of Hindi insisted on the superiority of Hinduism and refused any compromise with Muslims or Christians. Self-government, or swaraj, meant the rule of a Hindu majority. Hence, a body of literature poured forth evoking the myth of a glorious Indian past dominated by Hindu kings and philosophers, and a Hindu identity was represented as an "Indian" identity. For example, Shyam Narayan Pandey`s epics Haldighati and Jauhar depicted the heroism of Rajputs in resisting the invasions of the Turks and the Mughals. Stories of the greatness of Hindu gods were evoked through mythological tales from the Ramayana and the Mahabharata. Similarly, in Bhagavad Purana, Makhan Lal Chaturvedi attempted to reawaken a similar sense of duty in the Indian public as the characters in the Bhagavad Gita possessed.

In the field of drama, too, this trend became visible, especially in the historical plays of writers such as Jaishankar Prasad, Badrinath Bhatt, Makhanlal Chaturvedi, Bechan Sharma Ugra, and Govind Vallabh Pant. Called the most significant playwright of the twentieth century by Dashrath Ojha, Prasad`s historical dramas Ashoka (1912), Ajatshatru (1922), Chandragupta (1931), and Skandagupta Vikramaditya (1928) dwell on the courage of Hindu kings from ancient India. Shyam Sunder Simian`s historical plays, such as Chanakya Mohan, Haldighati, Padmini, and Kunal, also recuperated themes from history. Plays such as Makhanlal Chaturvedi`s Krishnarjun Yuddha, Govind Vallabh Pant`s Varmala, and Badrinath Bhatt`s Kuruvan Dahan, Durgavati, and Chandrakala Bhanukar continued to evoke images of a perfect Hindu society.

Hindu texts were also revived by Hindi nataka mandalis (play companies) to counter the Urdu movement. For example, Sri Ramlila Nataka Mandali presented Madhav Shukla`s Sita Swamvara based on Tulsidas`s Ramcharit Manas, Mahabharata, and Maharana Pratap and plays that satirized Urdu. These performances received immense popularity at the Hindi Sahitya Sammelan conferences at Allahabad and Lucknow.

Thus the Hindi literature in the pre-Independent era was focused on trying to bring about a revival of India`s past glory in order to unite the people and make them stand against the evils of foreign domination.

Hindi Literature in Post Independent Period

Hindi literature in the post-Independent period entered a new phase with the end of the freedom struggle and India`s Independence from colonial rule in 1947. Independence was accompanied by the subcontinent`s partition into India and Pakistan. Because of the violence that accompanied this geographical division, freedom generated rather mixed feelings. The jubilation of Independence soon changed into a mood of gloom as millions of people on both sides of the border were distressed by the agitation of communalism, alienation, and despair. The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948 dealt a further blow and shattered the confidence of the newly independent nation. The trauma of partition affected writers, who started questioning the idea of a nation that was invoked in earlier Hindi writings. While writers depicted the various outcomes of the partition on the masses, they also served to re-examine the implications and limitations of nationalism that caused untold misery and suffering for the many millions who were supposed to be liberated from foreign oppression. The tragic events that accompanied the partition of the country produced a sense of disillusionment and mourning. In literature, a conflict developed between the trend toward Western modernity and traditional Indian values. Social realism became a dominant trend in Indian literature. Representative of this movement are Muktibodh, writing in Hindi, and Vishnu Dey, in Bengali. In the 1970`s, the literary movement called post-modernism appeared in India.

Hindi literature in the post-Independent period entered a new phase with the end of the freedom struggle and India`s Independence from colonial rule in 1947. Independence was accompanied by the subcontinent`s partition into India and Pakistan. Because of the violence that accompanied this geographical division, freedom generated rather mixed feelings. The jubilation of Independence soon changed into a mood of gloom as millions of people on both sides of the border were distressed by the agitation of communalism, alienation, and despair. The assassination of Mahatma Gandhi in 1948 dealt a further blow and shattered the confidence of the newly independent nation. The trauma of partition affected writers, who started questioning the idea of a nation that was invoked in earlier Hindi writings. While writers depicted the various outcomes of the partition on the masses, they also served to re-examine the implications and limitations of nationalism that caused untold misery and suffering for the many millions who were supposed to be liberated from foreign oppression. The tragic events that accompanied the partition of the country produced a sense of disillusionment and mourning. In literature, a conflict developed between the trend toward Western modernity and traditional Indian values. Social realism became a dominant trend in Indian literature. Representative of this movement are Muktibodh, writing in Hindi, and Vishnu Dey, in Bengali. In the 1970`s, the literary movement called post-modernism appeared in India.

The partition became the predominant theme in the writings of Munto, Rajinder Singh Bedi, Bhisham Sahni, and others. Depressing conditions of Lahore slums and the poverty-stricken areas of Jalandhar were portrayed in Upendranath Ashok`s Girti Diwaren (1947). Other stories, such as Mohan Rakesh`s Andhere Band Kamare (1961) and Yashpal`s Jhutha Shak (1960) re-evaluated Hindu-Muslim relations against the backdrop of the partition. Agyeya published a collection of stories and poems about the partition called Sharnarthi (1948). In the preface to the collection, the author addresses the issue of communal violence, the horrors of war, and the perpetuation of communal conflict by the ruling class for their own political gains. A number of writers also found refuge in the literary journal Hans (1933-52) for expressing their ideological concerns about the partition and to draw attention to the disadvantaged and neglected groups.

All through the 1980`s the literary works focused on trying to convey the message of the uselessness of communal dissensions. In the decades after Independence, the situation was one of escalating communal tensions and the emergence of regional and local nationalisms in different parts of the country. By depicting the tragedy of the partition, writers such as Bhisham Sahni in recent decades have attempted to enlighten the public about how they are constantly being moulded into the ruling class`s scheme of a new nation. In Tamas (1976), Bhisham Sahni narrates the history of partition not as a history of communalism but as a problem that tore the moral and religious fabric of the country beyond repair. Sahni contrasts ordinary people from different religious groups with political leaders to show the ways in which the leaders schemed against the people for their own party interests. Sahni`s message is that, had the people understood the schemes of the rulers, both British and the Indian elite, they would have never encouraged or participated in the communal violence that ensued. One even finds in Tamas the interrogation of nationalism, not as a unified phenomenon but in terms of other groups such as the Dalits, peasants, and women.

Also during this time, in fact in the years immediately following independence, writers also turned to representations of villages after the breakdown of the old order. Phanishwar Renu`s Maila Aanchal (1954) takes us to a small village in Bihar to show the struggle between a stubborn zamindar and his landless workers. In Rag Darbari, Srilal Shukla shows how new forms of exploitation replaced old ones in the village. Much to his dismay, the protagonist of the story, a research student, goes on vacation to his uncle`s village and discovers that his uncle`s means of power are money, perjury, and exploitation of the poor. The author lashes out at corrupt politics through the locale of the village, which represents a microcosmic view of the situation at the center. Other stories, such as Nagarjun`s Balchnama (1952) and Bhagvati Prasad`s Mother Ganges (1953), centred their plots around village life and the struggle of labourers against zamindars.

It may be noted here that in the 1950s and 1960s the tendencies of New Criticism and modernism that were dominant in the West in the first half of the century infiltrated the Indian literary scene and had a direct influence on Hindi literature. These forms emerged in the Hindi Nai Kahani and the Nai Kavita movements of the 1950s. As literature`s preoccupation with formalism increased, writers adopted the rhetoric of a universalistic idiom and became predominantly concerned with purely aesthetic concerns. The strict adherence to prescribed forms and universalistic claims of literature became the basis for including texts into the canon of Hindi literature, resulting in the marginalization of significant writings that came from radical sectors as well as from women.

In the late 1960s and 1970s, the results of Independence started to become visible. While the metropolis seemed to progress, unemployment remained high, and large sections of the population remained below the poverty line. Such a climate gave rise to various protest movements, such as the anti price rise agitation of 1972-73, organized and led primarily by women. The 1970s also saw a vigorous involvement of women in social issues. Several women`s organizations were formed that protested against regressive traditions such as dowry and raised their voices against oppression of women. Feminist journals such as Manushi raised their voices against the repression of women. In 1975, the government declared a national emergency in the country, which suspended the fundamental rights of citizens until 1977, when the emergency was lifted. "Slum clearance" programs were initiated by the government, and the police cold-bloodedly razed "unsightly" urban settlements, rendering people homeless and helpless "with no legal avenues for appeal or protest".

Thus in the light of all these events, the decade of the 1970s gave birth to a radical new generation of political awareness and engagement. Writers questioned the inadequacies of democracy, which, contrary to its promises, and as the emergency revealed, did not seem to represent the interests of the people. Politically engaged writers made these themes the subjects of their writings, and the protagonists in the writings of the 1970s and 1980s were often lower-class people and women like Basanti, Bhisham Sahni`s protagonist in Basanti, a novel about slums and slum dwellers in Delhi. Basanti (1980) shows the impact of the government slum clearance schemes on lower-class people, especially on women like its protagonist. Basanti belongs to a lower-class and caste community that lost its livelihood during the country`s partition and moved to Delhi to revive its lost fortunes. The slum houses in which the community resides are brutally uprooted by police authorities, resulting in the dislocation of its residents without any help or compensation for the loss of their homes. While Sahni`s narrative constitutes an attack on repressive government policies, it is significant in showing the impact of the violence caused by national politics on the private space that Basanti occupies. To highlight class and social differences and the ramifications of social policy for different classes, Sahni juxtaposes Basanti with the upper-class Shyama bibi (mistress of the house), who remains imprisoned in her middle-class respectability.

The Hindi literary works in the post-Independent era thus display the angst and struggles of a newly-Independent country trying to attain socio-political stability and development.

Modern Period of Hindi Literature

The Adhunik kal or the Modern Period in Hindi literature commenced in the middle of the 19th century. The most decisive evolution of this period was the germination of Khari boli prose and abundant use of this standard Hindi dialect in poetry instead of Braj bhasha. Modern Hindi literature has been divided into four phases, comprising: the age of Bharatendu or the Renaissance (1868-1893), Dwivedi Yug (1893-1918), Chhayavada Yug (1918-1937) and the Contemporary Period (1937 onwards).

The Adhunik kal or the Modern Period in Hindi literature commenced in the middle of the 19th century. The most decisive evolution of this period was the germination of Khari boli prose and abundant use of this standard Hindi dialect in poetry instead of Braj bhasha. Modern Hindi literature has been divided into four phases, comprising: the age of Bharatendu or the Renaissance (1868-1893), Dwivedi Yug (1893-1918), Chhayavada Yug (1918-1937) and the Contemporary Period (1937 onwards).

The age of Bharatendu is exquisitely redefined by Bharatendu Harishchandra (1849-1882), considered the Father of Modern Hindi Literature. Harishchandra had brought in a completely contemporary outlook in Hindi literature hence totally justifies his title. Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi, ennobling the Dwivedi yug, later had taken up the vision of Bharatendu Harishchandra. Mahavir Prasad Dwivedi was an out-and-out reformist, who had ushered in an elegant and graceful style of writing in Hindi poetry, which later acquired a much deeper moral tone. This was the age of revival, when the stateliness and magnificence of ancient Indian culture was fully embraced to enrich modern life. Social, political and economic problems were gradually mirrored in poetry, while songs that were composed, emoted a theme of social awakening. This trend aided much to the crucial emergence of National Cultural Poetry, whose leading poets were Makhanlal Chaturvedi, Balkrishna Shama `Navin`, Siyaram Gupta and `Dinkar`. These poets exerted more emphasis on the moral aspect of life rather than on love or beauty, which later evolved in the Chhayavada style of poetry.

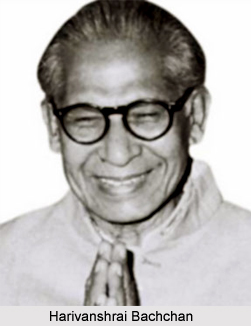

Kamayani was considered the most exalted point of this school of thought and Prasad, Nirala, Pant and Mahadevi best represented Chhayavada yug in the Adhunik kal of Hindi literature. After the downfall of this movement, the leftist ideology began to raise its head in a chronological sense, which found voice in two opposing styles of Hindi poetry. One was Progressivism and Prayogavada or later referred to as Nai Kavita. The former was an effort of translating Marx`s philosophy of Social realism into art. The most notable figure of this movement was Sumitranandan Pant. The latter had religiously made efforts to safeguard artistic freedom and brought in a new poetic content and talent, which reflected modern perceptivity. The pioneers of this trend were Aggeya, Girija Kumar, Mathur and Dharamvir Bharati. A third style called Personal Lyrics also had made an appearance, aiming at free and spontaneous human expressions with Harivansh Rai Bachchan serving as the leader of this trend. Harivansh Rai Bachchan indeed had bettered the world of Hindi poetry with his three exquisite collections comprising, Madhusala (1935), Madhubala (1936) and Madhukalas (1936). Bachchan`s poetry was considered wholly dissimilar from the romanticism of Chayavad and the ebullience of the Pragativad. His kind of poetry in Hindi contemporary period is sometimes referred to as `Hridayvad` or the poetry of passion.

Kamayani was considered the most exalted point of this school of thought and Prasad, Nirala, Pant and Mahadevi best represented Chhayavada yug in the Adhunik kal of Hindi literature. After the downfall of this movement, the leftist ideology began to raise its head in a chronological sense, which found voice in two opposing styles of Hindi poetry. One was Progressivism and Prayogavada or later referred to as Nai Kavita. The former was an effort of translating Marx`s philosophy of Social realism into art. The most notable figure of this movement was Sumitranandan Pant. The latter had religiously made efforts to safeguard artistic freedom and brought in a new poetic content and talent, which reflected modern perceptivity. The pioneers of this trend were Aggeya, Girija Kumar, Mathur and Dharamvir Bharati. A third style called Personal Lyrics also had made an appearance, aiming at free and spontaneous human expressions with Harivansh Rai Bachchan serving as the leader of this trend. Harivansh Rai Bachchan indeed had bettered the world of Hindi poetry with his three exquisite collections comprising, Madhusala (1935), Madhubala (1936) and Madhukalas (1936). Bachchan`s poetry was considered wholly dissimilar from the romanticism of Chayavad and the ebullience of the Pragativad. His kind of poetry in Hindi contemporary period is sometimes referred to as `Hridayvad` or the poetry of passion.

The period of incessant and contemporary growth in the Adhunik kal of Hindi literature is represented by Jayshankar Prasad (Chaya, Akash Deep), Rai Krishna Das and Mahadevi Varma. Munshi Premchand (1880-1936) was the greatest loyalist in the field of fiction. His immortal works in fiction comprise: Sevasadana, Premasrama, Nirmala, Kayakalpa, Rangabhumi, Ghaban and Godan. His last novel Godan has been translated in all the possible languages of India. Other important fictional Hindi writers of the contemporary period comprise: Jainendra Kumar (Sunita and Tyagapatra, Sukhada, Vivarta), Phanishwar Nath Renu (Maila Anchal), Satchinanda Vatsyayan (Sekhar Ek Jivani), Dharamvir Bharati (Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda), Yash Pal (Dada-comrade, Desh Drohi, Divya and Manusya Ke Rupa), Jagdamba Prasad Dikshit (Murdaghar) and Rahi Masoom Raza (Adha Gaon). Dr. Nagendra and Dr. Namwar Singh are the most respectable names in the arena of literary criticism. Upendranath `Ashk`, Jagdish Chandra Mathur (Konark), Lakshminarayan Lal (Sukha Sarovar) and Mohan Rakesh (Asadha Ka Ek Din, Lahraon Ke Rajahamsa and Adhe-Adhure) are renowned modern playwrights in Hindi.

The period of incessant and contemporary growth in the Adhunik kal of Hindi literature is represented by Jayshankar Prasad (Chaya, Akash Deep), Rai Krishna Das and Mahadevi Varma. Munshi Premchand (1880-1936) was the greatest loyalist in the field of fiction. His immortal works in fiction comprise: Sevasadana, Premasrama, Nirmala, Kayakalpa, Rangabhumi, Ghaban and Godan. His last novel Godan has been translated in all the possible languages of India. Other important fictional Hindi writers of the contemporary period comprise: Jainendra Kumar (Sunita and Tyagapatra, Sukhada, Vivarta), Phanishwar Nath Renu (Maila Anchal), Satchinanda Vatsyayan (Sekhar Ek Jivani), Dharamvir Bharati (Suraj Ka Satvan Ghoda), Yash Pal (Dada-comrade, Desh Drohi, Divya and Manusya Ke Rupa), Jagdamba Prasad Dikshit (Murdaghar) and Rahi Masoom Raza (Adha Gaon). Dr. Nagendra and Dr. Namwar Singh are the most respectable names in the arena of literary criticism. Upendranath `Ashk`, Jagdish Chandra Mathur (Konark), Lakshminarayan Lal (Sukha Sarovar) and Mohan Rakesh (Asadha Ka Ek Din, Lahraon Ke Rajahamsa and Adhe-Adhure) are renowned modern playwrights in Hindi.

The person who however ushered in an era of realism in the Hindi prose literature was Munshi Premchand, considered the most revered figure in the world of Hindi fiction and progressive movement. Before Munshi Premchand, Hindi literature in fact had pivoted around fairy or magical tales, stories of entertainment and religious themes. Premchand`s novels have since his advent, been translated into countless other languages. The history of Hindi literature, thus, extends well over a period of almost one thousand years.

Influences on Modern Hindi Literature

Influences on Modern Hindi Literature can be best understood by placing it against the backdrop of the socio-political conditions of Indian society in the twentieth century. The Indian nation witnessed important political changes during the period under consideration: from a colony of the British Empire it became an independent nation in 1947. The violence of colonialism, however bore heavily on the shaping of the nation. The struggle for independence from British colonial rule underwent a number of ups and downs before the arrival of freedom in 1947. Independence came with a price that was paid by the nation`s division into India and Pakistan. During the period of de-colonization since independence, the nation has undergone severe upheavals in the form of external aggressions, such as wars with Pakistan and China, and internal aggressions such as communal violence. This kind of a political upheaval both under British rule and after independence has played a definite role in the shaping of Hindi literature.

Influences on Modern Hindi Literature can be best understood by placing it against the backdrop of the socio-political conditions of Indian society in the twentieth century. The Indian nation witnessed important political changes during the period under consideration: from a colony of the British Empire it became an independent nation in 1947. The violence of colonialism, however bore heavily on the shaping of the nation. The struggle for independence from British colonial rule underwent a number of ups and downs before the arrival of freedom in 1947. Independence came with a price that was paid by the nation`s division into India and Pakistan. During the period of de-colonization since independence, the nation has undergone severe upheavals in the form of external aggressions, such as wars with Pakistan and China, and internal aggressions such as communal violence. This kind of a political upheaval both under British rule and after independence has played a definite role in the shaping of Hindi literature.

The manifestation of all these events is found in the multifaceted character of Hindi literature. A variety of themes are found represented in the Hindi literary works. These include the partition of the subcontinent, freedom from colonial oppression, freedom from internal hegemonies, freedom from the struggles of workers against various forms of exploitation, and feminist challenges to oppressive patriarchal structures and social traditions. These multiple themes and trends have been channeled through movements such as chayavad, or romantic literature; pragativad, or progressive realism; New Criticism; nai kahani or new short story; and feminist literature. Although some of these movements have been influenced by similar trends in the West, they emerged from their specific cultural traditions and sociopolitical milieus. These various voices have movements have both contributed to the process of nation building and addressed, at the same time, the sociopolitical problems within Indian society.

Broadly speaking, modern Hindi literature can be divided into two parts- pre-independence and post-independence at 1947, which heralded a new era of national independence as well as the nation`s partition into India and Pakistan. The first part deals with the emergence of nationalist thought and ideology in literary works of the period before independence. The nationalist politics of this era were accompanied by a controversy over the status of Hindi language and Urdu language, which created communal dissensions that ultimately jeopardized the possibility of a unified struggle against British imperialism. This linguistic controversy is significant, complicating the nationalist struggle against British imperialism by internal communal politics. Configuration of issues such as the partition, the urge for national unity, democracy and secularism in the 1950s, social issues related to village economies, and continuing problems of peasants, workers, women, and other marginalized groups constitutes, to a large degree, the subject matter of Hindi writings after independence and constitutes the second half.

However, there is one minor shortcoming when we try to analyze Hindi literature from this perspective. The chief drawback arises from an inability to define the exact parameters of Hindi literature because of overlaps between Hindi and Urdu. At present, the linguistic differentiation between these languages is rather unsettled. Despite the attempts to settle the differences between Hindi and Urdu since the second half of the nineteenth century, when the debate over linguistic classification first began, it remains difficult to make clear-cut demarcations. Writers who wrote in either of the languages have been co-opted into their respective literatures for political reasons. For example, Munshi Premchand, whose works have acquired a very important place in the canon of Hindi literature, wrote some of his works in Urdu before they were transcribed into Devanagari. The choice of the script was forced on him because of the increasingly difficult task of finding publishers for Urdu at a time when Hindi was being propagated as the national language. For the purposes of this chapter, I discuss primarily literature written in Devanagari.

However whatever the shortcomings it is evident that the influences on Modern Hindi literature have gone a long way in shaping the writing style and content of the literary works produced in the different periods under consideration.

Impact of National Unity and Reform on Hindi Literature

Impact of national unity and reform on Hindi Literature can be seen in the works of the era. The influence of these various factors can be best understood by looking at the various events that took place at the time. In 1906 the Hindu-Muslim conflict culminated in the partition of Bengal. British rulers at this time played on the communal divisions. The passed the Morley-Minto Reforms Act which gave patronage to Hindi and granted a separate electorate to the Muslims in 1909. As an effect of all these changes and occurrences in the Indian socio-political scenario, this phase witnessed the growth of a literature that emphasized Hindu-Muslim unity and evoked India`s historical past as an example of solidarity against the foreign powers. This was a trend that continued into the 1930s and 1940s as writers perceived the designs of British divisiveness of Hindus and Muslims in the interest of consolidating imperial rule. Signs of such an awareness became visible in plays like Swapan Bhang and Raksha bandhan, which expressed the theme of Hindu-Muslim unity. The aftermath of the partition led to the initiation of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal (1905-8). Poets such as Mahavir Prasad Dvivedi and Lakshmidhar Bajpai articulated their nationalist aspirations by satirizing and ridiculing foreign goods and urging the use of homespun cloth. Their message was that Swadeshi, which aimed at improving the conditions of Indian peasants through the use of indigenous goods, would bring back India`s prosperity.

Impact of national unity and reform on Hindi Literature can be seen in the works of the era. The influence of these various factors can be best understood by looking at the various events that took place at the time. In 1906 the Hindu-Muslim conflict culminated in the partition of Bengal. British rulers at this time played on the communal divisions. The passed the Morley-Minto Reforms Act which gave patronage to Hindi and granted a separate electorate to the Muslims in 1909. As an effect of all these changes and occurrences in the Indian socio-political scenario, this phase witnessed the growth of a literature that emphasized Hindu-Muslim unity and evoked India`s historical past as an example of solidarity against the foreign powers. This was a trend that continued into the 1930s and 1940s as writers perceived the designs of British divisiveness of Hindus and Muslims in the interest of consolidating imperial rule. Signs of such an awareness became visible in plays like Swapan Bhang and Raksha bandhan, which expressed the theme of Hindu-Muslim unity. The aftermath of the partition led to the initiation of the Swadeshi movement in Bengal (1905-8). Poets such as Mahavir Prasad Dvivedi and Lakshmidhar Bajpai articulated their nationalist aspirations by satirizing and ridiculing foreign goods and urging the use of homespun cloth. Their message was that Swadeshi, which aimed at improving the conditions of Indian peasants through the use of indigenous goods, would bring back India`s prosperity.

The socio-political message of mass unity intensified as Mahatma Gandhi, upon his return from South Africa in 1915, launched his anti-colonial campaigns for suffering peasants in Champaran, Bihar, in 1917 and against the zamindars in the Kaira district of Gujarat in 1918. A combination of Gandhi`s campaigns and the Swadeshi movement exerted a great influence on Hindi writers and brought forth a new outpouring of nationalistic literature, with Munshi Premchand as the most powerful spokesman of freedom. The writer resigned from his job as inspector of Government schools and increased his active participation in Gandhi`s movement to teach the villagers how to spin their own yarn and produce indigenous handmade cloth.

The socio-political message of mass unity intensified as Mahatma Gandhi, upon his return from South Africa in 1915, launched his anti-colonial campaigns for suffering peasants in Champaran, Bihar, in 1917 and against the zamindars in the Kaira district of Gujarat in 1918. A combination of Gandhi`s campaigns and the Swadeshi movement exerted a great influence on Hindi writers and brought forth a new outpouring of nationalistic literature, with Munshi Premchand as the most powerful spokesman of freedom. The writer resigned from his job as inspector of Government schools and increased his active participation in Gandhi`s movement to teach the villagers how to spin their own yarn and produce indigenous handmade cloth.

The influence of Gandhi`s Salt march (1930) and the second non-cooperation movement recast itself in his novel Karmabhumi, which propagates the effectiveness of public demonstrations. An anti-industrial outlook found its way in Premchand`s Rangbhumi (1925). In the novel, Premchand interrogates the effects of Western industrialization through a blind beggar`s struggles against a cigarette factory owner who establishes his factory next to the beggar`s piece of land. Premchand invokes the idea that the consequences of industrialization are brutal: the beggar is killed in his attempts to save his little plot of land that is threatened by the factory. Premchand also expresses the helplessness of the peasants amid rising industrial colonialism by showing the expansion of the factory despite the villagers` protests.

Hindu-Muslim dissensions deepened in the 1940s as the movement for a separate Pakistan became stronger. Hence, Hindu-Muslim unity became a popular theme for writers like Pant, Dvivedi, and Harivanshrai Bachchan, who lamented the possibility of the subcontinent`s break-up and reconstructed in their poems a nation devoid of religious, class, and caste distinctions.

Even the writings echoed modernity which was bathed by the rays of Nationalistic hues. Colonial modernity had indeed ushered an instigated plethora of cultural and political dimensions. The nexus of identity formation of the post colonial country and the formation of an individual tongue apart from the colonial language seemed to be the national fervour. Western influence on Hindi literature had cast its shadow by then. There had been a marked metamorphosis in the form, matter and the way of conglomerating the essence of Nationalism. Apart from the cultural and literary subjugation arose a new language which was influenced by the various "isms": Marxism, Feminism, Freudianism, etc within the framework of national penumbra.

Progressive Realism in Hindi Literature

Progressive Realism in Hindi Literature was compounded by a number of factors, prime among them being the atmosphere during the nationalist struggle. Mahatma Gandhi had tried to lessen the tension between the Hindu and Muslim communities by supporting Hindustani as the national language instead of Hindi or Urdu, which encouraged Hindu-Muslim separatism and kept the two communities disunited. Gandhi`s contention was that, since Hindustani was spoken by both the Hindu and the Muslim populace, it would prevent dissensions and promote national integration. However this Hindustani was to be in Devanagari and nor Arabic. This move caused immense disaffection among progressive intellectuals-both Hindu and Muslim. This disillusionment was further fuelled by Gandhi`s strategy of non-violence. For many people, especially those on the left, nonviolence had not shown conclusive results. The upsurge of anti-colonial nationalist ideas, World War I, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and continuing colonial exploitation created a mood of active political engagement. Influenced by Marxist ideas and inspired by the success of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, writers shifted their earlier Gandhian stance in favor of a more revolutionary ideology. This led to Progressive Realism in Hindi Literature.

Progressive Realism in Hindi Literature was compounded by a number of factors, prime among them being the atmosphere during the nationalist struggle. Mahatma Gandhi had tried to lessen the tension between the Hindu and Muslim communities by supporting Hindustani as the national language instead of Hindi or Urdu, which encouraged Hindu-Muslim separatism and kept the two communities disunited. Gandhi`s contention was that, since Hindustani was spoken by both the Hindu and the Muslim populace, it would prevent dissensions and promote national integration. However this Hindustani was to be in Devanagari and nor Arabic. This move caused immense disaffection among progressive intellectuals-both Hindu and Muslim. This disillusionment was further fuelled by Gandhi`s strategy of non-violence. For many people, especially those on the left, nonviolence had not shown conclusive results. The upsurge of anti-colonial nationalist ideas, World War I, the Great Depression of the 1930s, and continuing colonial exploitation created a mood of active political engagement. Influenced by Marxist ideas and inspired by the success of the Bolshevik revolution of 1917, writers shifted their earlier Gandhian stance in favor of a more revolutionary ideology. This led to Progressive Realism in Hindi Literature.

There were a number of disillusioned intellectuals and writers who initiated the formation of the Progressive Writers` Association in 1936, with Munshi Premchand as its pioneering member. Defining the banner of "progressive" as "all that arouses in us the critical spirit," writers proposed to turn literature into a weapon in the struggle against colonialism. The aim of the progressive writers was to portray an authentic picture of the problems of the marginalized masses through a realistic expression. This literature was to be expressed in a language easily understood by the masses. This brought about a shift from the "high" or Sanskritized Hindi propagated by the orthodox Hindu nationalists to a literature that used Hindustani. A move to realism also established the novel as the chief medium of expressing the political commitment of writers.

In this changing context, Premchand emerged as a key figure in exposing the evils of colonialism through a progressive, realistic style exhibiting the influence of Marxist ideas in stories such as Katil. Katil reveals an ideological shift from the non-violent path suggested by Gandhi to a revolutionary one. Premchand`s novel Premashram (1922) also focused upon issues concerning colonial exploitation through long descriptions of forced labor and the exploitation and use of poor peasants and their women at the hands of rich landlords. Premchand`s answer to freedom lay in collective peasant protests and the overthrowing of the ruling classes. Another realistic portrayal of colonial exploitation occurred in Rishabcharan Jain`s Gadar (The Revolution) in 1930 at the height of the nationalist movement. Not surprisingly, the novel was banned by the British government and reprinted only after Indian Independence from British rule.

The Progressive Writers` Association also strengthened the Hindi short story, a medium that had already been explored by Premchand and Jaishankar Prasad. As compared to full-length novels, the short story could convey the political message in a shorter space. Seen as a feasible means of communicating political messages, some writers, such as Yashpal, adopted this form for expressing their revolutionary views.

While prose remained the dominant form of expression during the 1930s and 1940s, progressive drama, too, played a significant role in attempting to dismantle existing power structures. Upendra Nath Ashok wrote plays such as Chhata Beta, Jai Parajai, Aadi and Marg. Others, such as Pandit Laxmi Narayan Mishra, expressed their socio-political estrangement through "problem plays" such as Sanyasis, Rakshas Ka Mandir, Mukti Ka Rahasya, Rajyoga, and Sindoor Ki Holi (Nagendra 1988, 645). Protest against problems of farmers, landlords, police, and inter-caste marriage, among others, came from Premchand in plays such as Sangrama and Prem Ki Vedi (1933).

The latter half of the 1920s and the decade of the 1930s saw the proliferation of one-act plays in Hindi, a number of which were also published in various journals, an example of which is Prashad`s Ek Ghunt. Hans, a journal edited by Premchand, published a special number on one-act plays in 1938. The shift from full-length plays to one-act plays was symbolic of a formalistic struggle that progressive playwrights waged against the power structures. On the one hand, it represented a break from the classical, full-length Sanskrit dramas that had acquired popularity because of the efforts to produce Sanskritized Hindi dramas by Hindu nationalist writers. Second, the one-act play in Hindi provided a break from the European full-length plays that used to dominate the theatres in the metropolitan during the twentieth century.

The one-act plays also proved immensely useful for propagating socio-political messages. Thus they were extremely advantageous as they were both entertaining and instructive, they cut down on the details of a full-length production, they came straight to the point, and they were easy to perform in towns and villages that lacked the requisite theatrical facilities. A number of progressive playwrights, such as Balraj Sahni, Khwaja Ahmad Abbas, and Rasheed Jehan, channeled their attacks on contemporary problems through the Indian People`s Theatre Association (IPTA), which was formed on an all-India basis in 1943 to use theater as a vehicle for social change. The IPTA set up a Hindustani squad that performed numerous plays on topics ranging from British imperialism, to fascism in Europe, to landlord problems, to exploitation of workers in factories, to the Bengal famine of 1943 and the cholera epidemic of 1944. Balraj Sahni and K. A. Abbas wrote and produced plays such as Zubeida, Yeh Amrit Hai etc.

The influence of Marxist ideas on Hindi writing continued into the 1940s. With their progressive outlook, writers such as Sohanlal Dvivedi and Sumitrananadan Pant, among others, continued to attack capitalist exploitation and the evils of imperialism and landlordism. The most scathing attack was launched on the imperialists after the Bengal famine of 1943, which, as politically committed writers believed, was created by the British government after the Quit India Movement of 1942. The famine had a crippling effect, and millions of lives were affected. Yashpal dealt with these themes in his novels Dada Comrade, Deshdrohi, Party Comrade, and Manushya Ke Rup.

Renaissance in Hindi Literature

Renaissance in Hindi Literature was somewhat different from what is called a social uprising. Where the Bengali Literature was playing a significant role to whip the rugged society of the time, Hindi literatures mainly accentuate a cultural development, which is much closer to the concept of Renaissance in Europe. The 20th Century Hindi Literature witnessed a romantic upsurge and insisted on the sheer rhythm & poise of the indigenous language.

The distinctive feature, explicit in the literary works of the period was the emotional attachment of the poets with the national freedom struggle & their effort to comprehend and imbibe the vast spirit of magnificent ancient culture. This tradition came to be existed as "Chyyavaad" tradition & the literary personalities following the tradition known as Chyyavaadi. Jaishankar Prasad, Suryakant Tripathi, `Nirala`, Mahadevi Varma and Sumitranandan Pant etc were the remarkable poets of the Chhyavadi trend.

One of the notable works of the period, Kamayani by Jaishankar Prasad, a perfect amalgamation of knowledge, action & desires of life represented the spirit of Renaissance. Nirala`s style of verse in Anaamika & Parimal induced revolution in his time & accented his protest against the social exploitation. An amalgamation of the Vedanta philosophy with nationalism & mysticism was the chief feature of the works of the period. Saroj Smriti of Nirala was one of the magnificent works of the era. Lokayatan Pallavni by Sumitranandan Pant featured his progressive, philosophical & social outlook. A new tradition - Rahasyavad was introduced in Hindi Literature by Mahadevi Varma, with a different stance about the Lord of Universe. Deepsikha & Yama by Mahadevi Varma bear the specimen of ardent feminism. Mamta, Samudragupta, Dhruvaswani, Veena, Uchchavas, Granthi, Pallava, Gunjan etc were the principal works of the period.

One of the notable works of the period, Kamayani by Jaishankar Prasad, a perfect amalgamation of knowledge, action & desires of life represented the spirit of Renaissance. Nirala`s style of verse in Anaamika & Parimal induced revolution in his time & accented his protest against the social exploitation. An amalgamation of the Vedanta philosophy with nationalism & mysticism was the chief feature of the works of the period. Saroj Smriti of Nirala was one of the magnificent works of the era. Lokayatan Pallavni by Sumitranandan Pant featured his progressive, philosophical & social outlook. A new tradition - Rahasyavad was introduced in Hindi Literature by Mahadevi Varma, with a different stance about the Lord of Universe. Deepsikha & Yama by Mahadevi Varma bear the specimen of ardent feminism. Mamta, Samudragupta, Dhruvaswani, Veena, Uchchavas, Granthi, Pallava, Gunjan etc were the principal works of the period.

Women Writers in Hindi Literature

Women writers in Hindi Literature carved out their own spaces in order to address issues such as marriage, divorce, sexuality, and women`s education, that is, issues that directly affect women`s lives. Although male writers such as Munshi Premchand, Jainendra Kumar, Rajender Singh Bedi, and Bhisham Sahni attempted to deal with problems that women face in Indian society, they accorded women spaces that were conceived according to their own social visions. Hence, what was ascribed to women were spaces designated from a male viewpoint. In course of time, women writers in Hindi Literature when confronted with such problems, interrogated in their writings the cultural traditions and the modern uses of patriarchal power in independent India. Many of these women have challenged the power structures that assign them sub-ordinate positions even while keeping some of the traditions intact. They discuss their frustrations and humiliations stemming from social problems that affect their daily lives.

Women writers in Hindi Literature carved out their own spaces in order to address issues such as marriage, divorce, sexuality, and women`s education, that is, issues that directly affect women`s lives. Although male writers such as Munshi Premchand, Jainendra Kumar, Rajender Singh Bedi, and Bhisham Sahni attempted to deal with problems that women face in Indian society, they accorded women spaces that were conceived according to their own social visions. Hence, what was ascribed to women were spaces designated from a male viewpoint. In course of time, women writers in Hindi Literature when confronted with such problems, interrogated in their writings the cultural traditions and the modern uses of patriarchal power in independent India. Many of these women have challenged the power structures that assign them sub-ordinate positions even while keeping some of the traditions intact. They discuss their frustrations and humiliations stemming from social problems that affect their daily lives.

Thus there are women writers like Rajni Pannikar, Krishna Sobti etc who address the issue of the subjugation of women in society. Krishna Sobti also opposes the traditional moral values imposed on women. In most of her novels, Shivani opens up numerous windows on the lives of women. She asserts that the tradition-bound, male-dominated system leaves no space for women`s individuality. Shivani contends that a woman may be treated as a goddess or as a `Sati,` but actually her position is no more than that of a servant. Her novels reveal that even in the contemporary milieu, women`s situation is no different from the repressive conditions of the nineteenth century that had urged the need for social reforms. In Chaudah Phere, Shivani, through the colonel, his wife, and their daughter Ahilya, exposes the social system. She puts forward the view that in the male-dominated Indian society, a man assumes the rights to behave with a woman in whichever way he likes. Despite Ahilya`s protests, her father the colonel forces her to marry the man he chooses as her husband. The colonel himself has an affair with Malika Sarkar, depriving his wife of all her rights in the house. In Rativilap, Shivani portrays the difficulties of a widow. In spite of being educated, Mayapuri`s Shobha, finds herself caught in a web of difficulties. Helpless and trapped, she silently suffers when her poverty, class, and caste prevent her from marrying her lover, Satish, who brings the governor`s daughter home as his bride.

Like Mayapuri`s Shobha, the protagonist in Usha Priyamvada`s Pachpan Khambe Lal Diwaren is prevented from marrying the man she loves because it is socially unacceptable. Burdened by poverty and her family`s financial crisis, she takes up a job as the warden of a hostel and becomes a prisoner in the building with red walls and 55 pillars.

A number of stories written by women foreground the problems pertaining to marriage. The Indian social system allows little choice to women in the matter of selecting their husbands. For the most part, parents make decisions about matrimony and, in accordance with the Shastras, gift the girl to the groom`s family through a ritual called kanyaadan (giving of the bride), accompanied by a dowry that serves as a reimbursment to her husband`s family. Unfortunately, the practice of giving dowry has resulted in the commoditization of women and encourages, at the same time, mismatched marriages because of poverty. While rich men claim an untold price for their sons, the poor are forced to sell their daughters to men because of economic helplessness. Rajni Pannikar speaks out against this situation in her novels. Because of her family`s inability to give dowry, the heroine of Do Ladkiyan remains unmarried. On the night of her wedding, the vows cannot be taken because the prospective groom and his father angrily disrupt the ceremony upon realizing that no dowry will be provided. Helpless, she takes up a job to solve her family`s financial difficulties. In the meantime, she meets the wealthy Mr. Kanaudia, who wants to make her his private secretary. In exchange, he offers her a car, a bungalow, and other facilities. She accepts his terms only to later realize his sexual intentions toward her. Kanaudia views her as no more than a female body for his sexual exploits. Pannikar`s attempt is to enlighten us about the regressive aspects of a rigid and tradition-bound system.

A number of stories written by women foreground the problems pertaining to marriage. The Indian social system allows little choice to women in the matter of selecting their husbands. For the most part, parents make decisions about matrimony and, in accordance with the Shastras, gift the girl to the groom`s family through a ritual called kanyaadan (giving of the bride), accompanied by a dowry that serves as a reimbursment to her husband`s family. Unfortunately, the practice of giving dowry has resulted in the commoditization of women and encourages, at the same time, mismatched marriages because of poverty. While rich men claim an untold price for their sons, the poor are forced to sell their daughters to men because of economic helplessness. Rajni Pannikar speaks out against this situation in her novels. Because of her family`s inability to give dowry, the heroine of Do Ladkiyan remains unmarried. On the night of her wedding, the vows cannot be taken because the prospective groom and his father angrily disrupt the ceremony upon realizing that no dowry will be provided. Helpless, she takes up a job to solve her family`s financial difficulties. In the meantime, she meets the wealthy Mr. Kanaudia, who wants to make her his private secretary. In exchange, he offers her a car, a bungalow, and other facilities. She accepts his terms only to later realize his sexual intentions toward her. Kanaudia views her as no more than a female body for his sexual exploits. Pannikar`s attempt is to enlighten us about the regressive aspects of a rigid and tradition-bound system.

The problems of arranged marriage is manifested in Shivani`s Kainja, whose heroine, Nandi Tiwari, is not allowed to marry the man she chooses, because her father has been told that her horoscope does not predict a happy married future.

The problem of dowry compounded by widowhood is considered in Mrinal Pandey`s short story "Hum Safar." Through the thoughts of a young widow, Nirmala, traveling in a train compartment, Pandey illuminates the bitter truth about the ways in which her widowhood denies her whatever little she has left to savor. Nirmala recalls that after her husband`s death, her colored Saris and blouses, her silver anklets and nose ring, all had slowly found their way into her sister-in-law`s boxes. Thus through the story Pandey tries to challenge the existent social structure which affects and moulds a widow`s world. To confront the violence committed on women in their daily lives, Pandey introduces a language of violence expressed in Nirmala`s outrageous beating of her son. What is expressed in this action is that a quiet and non-violent, passive attitude that society expects from a "virtuous" woman is insufficient to confront the violence inflicted on women through male-dominated structures.

Stories written by women largely reveal women`s desires to have the choice to shape their lives, especially marriage, something that existing social institutions do not grant. Although Mannu Bhandari sees marriage as a necessity, she recommends the choice of divorce in an unsuccessful marriage. At the same time, however, she highlights the social problems attached to the status of being a divorced woman in Ap Ka Band (1971).

Most of the stories of Pannikar, Shivani, Mannu Bhandari, and Mrinal Pandey strongly convey the necessity for women`s education for achieving social and economic equality. For this reason, their protagonists are often educated women. The heroine of Do Ladkiyan is professionally sound because of her education. Similarly, Kainja`s Nandi Tiwari fights the system by obtaining a medical degree, which enables her to become a successful doctor. Her education provides her a self-confidence and economic stability that enable her to face the repressive society.

Thus women writers in Hindi Literature have proved extremely progressive in their questioning of the social structures which confined. The stories written by these women introduce old issues, but with new emphases and new orientations.

Chhayavad in Hindi Literature

Chhayavad in Hindi literature was a trend in the 1920s and the 1930s when there was seen the profusion of a literature that exhibited a romanticism and mysticism, especially in poetry. Chhaya, which literally translates as "a reflection, an image in a mirror," emerged as a revolt against Khadi boli poetry, which had replaced Braj poetry by the beginning of the twentieth century. As a result of the efforts of the Orthodox Hindus to propagate the use of Hindi language, Khadi Boli had experienced a formalistic transformation that imparted a literary character to the language. The poetry that emerged out of Hindu revivalism was full of the images of a lost past. They reflected communal and revivalist ideals and strong feelings of patriotism and nationalism. However, these feelings were coloured by the Hindu ideals which did not help in encouraging secular ideals or in the development of a more progressive Indian society.

Chhayavad in Hindi literature was a trend in the 1920s and the 1930s when there was seen the profusion of a literature that exhibited a romanticism and mysticism, especially in poetry. Chhaya, which literally translates as "a reflection, an image in a mirror," emerged as a revolt against Khadi boli poetry, which had replaced Braj poetry by the beginning of the twentieth century. As a result of the efforts of the Orthodox Hindus to propagate the use of Hindi language, Khadi Boli had experienced a formalistic transformation that imparted a literary character to the language. The poetry that emerged out of Hindu revivalism was full of the images of a lost past. They reflected communal and revivalist ideals and strong feelings of patriotism and nationalism. However, these feelings were coloured by the Hindu ideals which did not help in encouraging secular ideals or in the development of a more progressive Indian society.

The chhayavadis revolted against this rigid control of poetry, which severely curtailed artistic freedom. They propagated the free flow of artistic expression, through which they expressed the problems and disillusionment of the individual in a world gone wrong. The shift toward romanticism was also symbolic of the writers` protests against British colonialism. By the end of World War I, British exploitation had reached its peak, and the nationalist struggle was at its height. Romantic writers sought an escape from the tedious conditions of life by creating an imaginary world for themselves. To look for solutions to existing political problems, the chhayavadis turned to an infinite transcendental reality, holding on to the expression of mysticism and spiritualism. The chhayavadi phase emerged from the cultural conditions within Indian society and thus differed from the Romantic Movement in the West.

The chief proponents of the Chhayavad movement were Jaishankar Prasad, Suryakant Tripathi `Nirala`, Sumitranandan Pant, and Mahadevi Verma. Nirala`s first romantic poem, entitled "Juhi Ki Kali" (The Bud of Jasmine) was published in 1923. Within a short span of time, poets such as Makhan Lal Chaturvedi, Ram Kumar Verma, Bhagvati Charan Verma, Harivanshrai Bachchan, Narendra Sharma, Uday Shankar Bhatta, and Kedar Nath Bhatta became established as romantic poets. Preoccupied with symbolist experiments, poetic lyricism, and mysticism, the nationalistic themes of the Chhayavadi writers became replete with such imagery. Nirala`s Anamika (1937) is the most representative collection of the Chhayavadi writers. Others, such as Pant`s collection of poems Vani (1927), Pallava (1928), and Gunjan (1932), express the loneliness of the poet in a world of chaos.

The revolutionary upsurge in literature and the concern with mass nationalist struggle caused a shift from the personal struggles undertaken by the romantics to a depiction of the struggles of the masses. Chhayavadi writers such as Jaishankar Prasad, Suryakant Tripathi `Nirala` (1896-1961), Sumitranandan Pant, and Mahadevi Verma started finding their preoccupations with the lyrical charm and idyllic beauty of poetry limited and moved on to explicit social themes. Poems such as Mahadevi Verma`s "Yama" and "Deepshikha" (1940), Harivanshrai Bachchan`s "Madhushala" (1935), and Pant`s "Yuganta" (1939) and "Gramya" (1940) are reflective of this shift. The poems portray poverty, social inequality, and village life. Surya Kant Nirala`s Kukurmutta (1941) is a powerful attack on the British and Indian ruling classes through the Kukurmutta`s (mushroom`s) chastisement of the rose, which is presented as a metaphor for the capitalistic designs of the rulers.

Thus, the Chhayavad movement in Hindi literature was a definite shift away from the earlier pre-occupations of the writers to a Romantic mysticism.