A lot of changes have come about in Jainism under the Maurya Empire. Rather it can be said that significant changes took place in the church during the period when Jaina-faith blossomed in the Maurya-empire. Accounts about Jainism under the Maurya rule say that there was a great famine in Bihar during Chandragupta`s Rule. Bhadrabahu, the head of the community at that time, realized that it was not possible either for people to feed a great number of monks under these circumstances, or for ascetics to follow all the precepts. He, therefore, thought that it was advisable to immigrate with a group of devotees to Karnataka, while the remaining monks stayed back in Magadha under the supervision of his pupil Sthulabhadra.

A lot of changes have come about in Jainism under the Maurya Empire. Rather it can be said that significant changes took place in the church during the period when Jaina-faith blossomed in the Maurya-empire. Accounts about Jainism under the Maurya rule say that there was a great famine in Bihar during Chandragupta`s Rule. Bhadrabahu, the head of the community at that time, realized that it was not possible either for people to feed a great number of monks under these circumstances, or for ascetics to follow all the precepts. He, therefore, thought that it was advisable to immigrate with a group of devotees to Karnataka, while the remaining monks stayed back in Magadha under the supervision of his pupil Sthulabhadra.

The unfavourable period burned heavily on the monks so that they could not strictly observe the holy customs any more and maintain faithfully the Holy Scriptures. It was, therefore, found to be necessary to acquire the canon anew. A council was called for this purpose in Pataliputra. But this symbol of the church did not succeed in putting together the whole canon; the anthology published by it also remainded a patchwork, and when the monks who had emigrated to Karnataka returned home, they did not approve the resolutions of the council. Besides, there was, according to the tradition, a difference in the ascetic conduct of life between those who had emigrated and those who had stayed back.

Historical records during the Maurya Empire say that the followers of Parshvanatha were allowed to wear clothes, whereas the followers of Lord Mahavira did not wear any clothes. Monks staying back in Magadha gave up the custom of moving around in nude and got accustomed to wearing white garments. The emigrants did not only keep to the custom practised by Mahavira, but it was even generally regarded as obligatory. When they returned to Magadha and found that their brothers were wearing white clothes, they had to appeal to them as the people who had abandoned the whole practice, whereas those who stayed back saw in the naked emigrants` fanatics who gave exaggerated interpretation to the precept bequeathed by tradition. Thus there came an estrangement between the two trends, the stricter one of the "Digambaras" (those clothed in the air) and the freer one of the "Swetambaras" (those clothed in white), which finally led, although much later, to a complete schism.

Historical records during the Maurya Empire say that the followers of Parshvanatha were allowed to wear clothes, whereas the followers of Lord Mahavira did not wear any clothes. Monks staying back in Magadha gave up the custom of moving around in nude and got accustomed to wearing white garments. The emigrants did not only keep to the custom practised by Mahavira, but it was even generally regarded as obligatory. When they returned to Magadha and found that their brothers were wearing white clothes, they had to appeal to them as the people who had abandoned the whole practice, whereas those who stayed back saw in the naked emigrants` fanatics who gave exaggerated interpretation to the precept bequeathed by tradition. Thus there came an estrangement between the two trends, the stricter one of the "Digambaras" (those clothed in the air) and the freer one of the "Swetambaras" (those clothed in white), which finally led, although much later, to a complete schism.

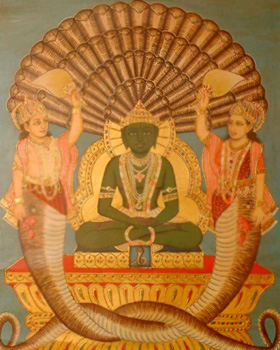

It is possible that there had been since time immemorial two trends in Jainism, a stricter one, which adhered to Mahavira`s rule and a milder one, which obeyed Parshvanath`s more liberal precepts. The most conspicuous of these differences concerning the garments of the ascetics does not appear to be so strict now; because the number of the naked Digambara- monks at present is quite negligible, besides they are also in secluded places. On the other hand, there are even now important differences in the social organization of the two sects; they trace back to the original differences in faith and rites: Digambaras think that a woman can never get salvation; their cult idols show the Tirthankaras naked without a loincloth and without ornaments. Swetambaras show these on their idols.

The different attitude taken by the two sects with respect to holy tradition has a far-reaching importance. Both teach that Bhadrabahu had been the last Srutakevali and that the teachers after him did not possess any knowledge of all the Holy Scriptures. But while Digambaras believe that the canon has been gradually completely lost so that it does not exist now, Swetambaras presume that its main part has come down to the present day. When there was a danger of the collection of the holy scriptures, as far as they had been saved through the stormy times, being lost, Swetambara called a meeting of the council in the year 980 (or 993) after Mahavira`s Nirvana under the chairmanship or Devarddhi Gani in the city of Valabhi in Gujarat; this finally edited the canon, and it gave it a form which it is said to possess even now for the most part.

Although Swetambaras have a canon and Digambaras do not have it, and although there are differences in the dogmatism and the cult of the two sects, the dividing line between them, in spite of all antagonism and hatred, had never been so strong. Both the orientations have been constantly aware of their common origin and goal and have never lost spiritual contact with each other. This is most clearly seen in the fact that the members of one group very often use philosophical and scientific works of other and that Swetambaras have written commentaries on the works of Digambaras and vice versa.