Introduction

Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II served as the fourteenth Maharaja of the Kingdom of Mysore, ruling from 1673 to 1704. He hailed from Wodeyar family of Mysore. Under his reign, the kingdom witnessed notable territorial expansion beyond what was achieved by his predecessors. Mysore also received the recognition from the Mughal Empire as a tributary state in the Southern part of India. His era also marked a remarkable consolidation of centralized military power, reaching a level previously unseen in the region.

Early Life of Chikka Deva Raja Wodeyar

Chikka Devaraja was born on September 22, 1645, as the eldest son of Maharani Amrit Ammani and Dodda Deva Raja, the elder brother of Devaraja Wodeyar I and a former governor of the Mysore town. Following the death of his uncle on 11 February 1673, Chikka Devaraja ascended the throne and was formally crowned on February 28 of the same year. Building on his predecessor’s expansionist policies, he captured Maddagiri, which brought Mysore’s territory into direct contact with the Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat province governed by Venkoji, the Raja of Tanjavur and half-brother of Shivaji.

In the first decade of his rule, Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II introduced

various petty taxes that were mandatory for the peasants, but that his soldiers

were exempted from.

Tax Rebellion and the Suppression of the Jangamas

During the early years of his reign, Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II imposed a series of petty taxes on peasants, from which his soldiers were notably exempted. The heavy burden of these levies, coupled with the intrusive nature of his administration, sparked widespread discontent among the ryots. Their resistance gained further strength through the support of the Jangama priests of the Virasaiva monasteries.

Determined to end the unrest, the king resorted to a ruthless stratagem. He invited more than 400 Jangama priests to a lavish feast at the prominent Shaivite centre of Nanjanagudu. After the banquet, the priests were presented with gifts and directed to leave one by one through a narrow passage. Waiting there were the royal wrestlers, who strangled each priest in turn. This calculated and brutal massacre effectively silenced opposition to the new taxation system.

Around the same period, in 1687, Chikka Devaraja attempted

to acquire Bangalore

(now Bengaluru) from Venkoji, the Raja of Tanjore and half-brother of Shivaji,

for a payment of three lakh rupees. While the negotiations were underway,

however, the Mughal

army under Khasim Khan seized the city and raised the Mughal flag over

its ramparts on July 10, 1687. When the Marathas sought to retaliate, Chikka

Devaraja sided with the Mughals, even fighting before the walls of Bangalore in

hopes of gaining Aurangzeb’s

favor. Ultimately, the transfer deal that had begun with the Marathas was

concluded under Mughal authority.

Alliance and Recognition from the Mughal Empire

During the reign of Aurangzeb, the Mughal empire extended its control into the Vijayanagara region, incorporating the Maratha-Bijapur province of Carnatic-Bijapur-Balaghat, which was a part of Bangalore (now Bengaluru). This region was merged into the Mughal province of Sira. As a result, the payment for Bangalore was not made to the Marathas but to Khasim Khan, the Mughal Faujdar-Diwan of Sira. Through this arrangement, Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II carefully cultivated an alliance with the Mughals, seeking to strengthen ties with Aurangzeb.

While maintaining this relationship, he shifted his focus southwards, targeting regions less influenced by Mughal authority. Mysore annexed Baramahal and Salem, located below the Eastern Ghats, and in 1694, extended control westward to the Baba Budan Mountains. Two years later, Devaraja Wodeyar II advanced against the Naiks of Madurai and laid siege to Trichinopoly.

Following the death of Khasim Khan, however, Mysore’s direct Mughal link was weakened. To renew imperial favor and secure recognition of his southern conquests, Devaraja Wodeyar II dispatched an embassy to Aurangzeb at Ahmadnagar. In 1700, the emperor acknowledged his loyalty by sending a signet ring seal conferring the title “Jug Deo Raj” (“lord and king of the world”), the right to sit on an ivory throne, and a ceremonial sword (firangi) from Aurangzeb’s own regalia, richly adorned with gold etching. This sword was henceforth used by Mysore rulers as the State sword during court ceremonies.

At this time, Devaraja Wodeyar II also reorganized Mysore’s

governance into eighteen administrative departments, famously known as the

athaara kacheri (eighteen offices), modeled on the Mughal system his envoys had

observed. By the time of his death on November 16, 1704, Mysore’s dominions

stretched from Medigeshi

in the north to Palni

and the Anaimalai

Hills in the south, and from Kodagu and Balam

in the west to the Baramahal region in the east.

Administration under Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II

Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II was recognized as an able administrator whose court attracted numerous scholars. At the heart of his governance was a council of ministers, which functioned as a powerful advisory body. However, their roles were not rigidly defined, as the king himself remained the fountainhead of all authority. During military campaigns, it was this council that oversaw the day-to-day administration of the kingdom.

Defense and security were central to his policies. Under his rule, the Mysore army expanded not only in manpower but also in weaponry, reflecting a steady evolution of military capability. Law and order were given equal emphasis, reinforcing stability within the expanding state. The taxation system was revised, and contemporary records note that revenues amounting to two bags of 1,000 varahas each were deposited daily in the royal treasury.

Chikka Devaraja also introduced significant economic and administrative reforms. He standardized weights and measures, facilitating consistency in trade and governance. Iron production became an important industry, while artisans such as weavers, dyers, tailors, plasterers, and basket makers received royal patronage. Additionally, forts acquired during Mysore’s territorial expansion were renovated, with marketplaces carefully planned within them, further integrating commerce and defense.

The first major expansion of Kempegowda’s Bengalore is credited to Chikka Deva Raja Wodeyar, who constructed a large oval-shaped mud fort to the south of the old township. This new stronghold later came to be known as the ‘pete’ fort, while the enclosed area was referred to as the ‘kote.’ Even today, several lanes and bylanes in this part of Bengaluru preserve these historic names.

The fort was built with a clear strategic purpose: to

strengthen Bengaluru’s defenses against recurring Maratha raids into Mysore

territory. Chikka Deva Raja was the first Mysore ruler to recognize the city’s

military significance and took decisive steps to fortify it as a citadel of

defense. His foresight ensured that Bangalore, (now Bengaluru) became the

kingdom’s first line of protection, reinforced by the nearby hill forts of

Savana Durga and Devarayana Durga. The fact that Mysore later withstood repeated

assaults by both the Marathas and the British owes much to the foundations laid

by Chikka Deva Raja, who spared no effort in transforming Bengaluru into a

formidable bastion.

Religious Reforms under Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II

The reign of Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II marked a significant phase in the consolidation of Vaiṣṇavism as the professed faith of Mysore’s royal dynasty. Centres such as Melkote and Seringapatam emerged as major strongholds of Vaiṣṇava tradition during this period. At the same time, other faiths, including Jainism, continued to flourish within the kingdom, reflecting its religious diversity.

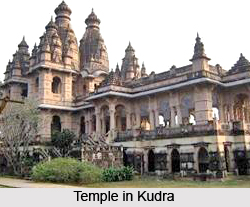

One of the king’s earliest acts of devotion was the construction of a temple dedicated to Lord Paravasudeva on the banks of the Kaundini River, intended as a meritorious offering for the salvation of his father’s soul. He also commissioned temples at Seringapatam, Haradanahalli, and Varakoclu, while numerous older shrines were renovated under his patronage.

Chikka Devaraja also undertook ambitious projects with both

religious and practical significance. In 1700, he launched a large-scale

irrigation scheme by damming the Kaveri River

and excavating canals along both banks. However, the project was short-lived,

as heavy monsoon rains destroyed the dam soon after its completion.

Role of Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II in the Battle of Banavar

The Battle of Banavar in 1682 was a major confrontation between the Maratha Empire and the Kingdom of Mysore. Under the leadership of Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II, the Mysore forces decisively defeated the Marathas and their allies commanded by Sambhaji, forcing the Maratha king to retreat, though temporarily.

Prelude to the Battle of Banavar

The conflict between Mysore and the Marathas had deep roots.

Sambhaji’s grandfather, Shahaji, had earlier entered Karnataka after receiving

the jagir of Bangalore from Mohammed Adil

Shah of Bijapur, marking the Maratha foothold in the south. Later,

Shivaji’s southern campaigns (1676–78) expanded Maratha influence, bringing

them into direct competition with Mysore for regional dominance.

Relations between the two powers were hostile. In 1681, the Marathas attacked Srirangapatna but were repelled. Around the same time, Chikka Devaraja sought control of Trichinopoly, ruled by Chokkanath of Madurai. Chokkanath requested aid from Harji Mahadik, the Maratha commander at Jinji. Mysore’s commander Kumarayya attempted to isolate Chokkanath by bribing Mahadik, hoping he would abandon Sambhaji. Secretly, Kumarayya also requested reinforcements from his king but his letter fell into Maratha hands.

When Harji Mahadik discovered this, he launched a counteroffensive and sent a large force under Dadaji Kakade, Jaitaji Katkar, and others into Mysore territory. They encamped at Kottatti and Kasalagere in present-day Mandya district. Chikka Devaraja ordered Kumarayya to respond, but Mahadik defeated him. Both sides, however, remained locked in stalemate.

In June 1682, Sambhaji personally led a coalition into Mysore, supported by the Nayakas of Keladi and the Qutb Shahi dynasty. Their forces reached Banavar, where Lingappa, the Mysore officer stationed there, quickly alerted Chikka Devaraja.

Deployment and Tactics at Banavar

Chikka Devaraja acted swiftly, marching with a strong

contingent of 15,000 skilled archers, determined to strike before the allies

could fully establish themselves. Early skirmishes broke out, but the tide

turned once he realized the allied army lacked archers.

He deployed his forces in a semicircular formation, unleashing relentless volleys of arrows. The Marathas, unprepared for this tactic, suffered heavy casualties. Despite attempts by Maratha commanders to regroup and reinforcements arriving mid-battle, the allied army remained vulnerable. Sambhaji’s troops faltered under sustained losses, while Mysore’s archers even paused to take their evening meal before resuming the assault. Eventually, Sambhaji was forced to retreat eastward toward Thanjavur to secure additional supplies.

When he returned, Sambhaji adapted to Mysore’s tactics, equipping his soldiers with oil-coated, shot-proof leather jackets and deploying explosive arrows to counter the archers.

Consequences and Aftermath

The victory at Banavar was a significant triumph for Mysore,

commemorated by Chikka Devaraja through an inscription. However, Sambhaji soon

regained momentum in subsequent campaigns, using his new innovations to defeat

Mysore forces. He went on to capture several fortresses in the northern Madurai

region, limiting the lasting impact of Mysore’s initial success.

Legacy of Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II

The legacy that Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II left to his successor was marked by both strength and fragility. Under his rule, Mysore had expanded steadily from the mid-seventeenth to the early eighteenth century, yet much of this growth was dependent on shifting alliances that often undermined long-term stability.

Some of his southeastern acquisitions, such as Salem, though not contested directly by the Mughal Emperors, were secured through cooperation with Khasim Khan, the Mughal Faujdar-Diwan of Sira, and Venkoji, the Maratha ruler of Tanjore. These partnerships, however, proved unstable. For instance, the siege of Trichinopoly had to be abandoned when one such alliance began to collapse.

The embassy he dispatched to Aurangzeb in 1700 also reflected this dual nature of his legacy. While it brought prestige in the form of a royal seal, a ceremonial sword, and recognition by the Mughal emperor to the Deccan, it also placed Mysore in a position of formal subordination to Mughal authority, obliging the kingdom to pay an annual tribute.

Even the administrative reforms during his reign, such as

the establishment of the celebrated athaara kacheri or eighteen departments,

may have been directly inspired, if not influenced, by Mughal models. Thus,

while Chikka Devaraja strengthened Mysore’s territorial and administrative

foundations, the reliance on external alliances and Mughal recognition left the

state both empowered and constrained.

Literary Contributions of Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II

Chikka Devaraja Wodeyar II was not only a ruler but also a devout and learned Srivaiṣṇava, a fact reflected in his surviving literary works. Two of his compositions have endured, namely the Gitagopalam and the Cikadevaraya Binnapaṃ.

The Gitagopalam is a musical-poetic work celebrating the life and divine glories of Krishna. It is described as a “celebration of Hari, conducive to the final liberation,” reflecting its devotional and philosophical purpose. Many scholars have speculated that the king’s court poet, Tirumalarya, who also composed his vaṃsavali (genealogy), may have played a role in organizing the work.

His second composition, the Binnapaṃ, is a theological text written in verse. It addresses several central doctrines of Srivaiṣṇava philosophy, further highlighting Chikka Devaraja’s religious commitment and intellectual engagement with theological discourse.