Assamese Novel under Rajanikanta Bardoloi witnessed what it had to, the towering heights of social and psychological realism. Though Rajanikanta Bardoloi has contributions to other branches of literature, he is widely known as a great novelist. He had a reverence for the past and for Assam`s cultural and literary heritage, and was always inspired by a lofty idealism. His novels aim at rousing a regard for the rich heritage of Assam. He held up high moral standards before people, and for numan weakness he had the largest sympathies. Equally disposed to all classes of people, he assayed a Comedie Humaine, darting like a traveller from one swarming city or countryside to another with an abundance of human sympathy. He believed that life after all is one and that mutual regard would not cost anything and would remove unhappiness. Primal passions that ultimately count have their soil in every human heart and do not abide any distinctions of class or caste or community. He was thus the most large-hearted and the most felicitous of our novelists.

Assamese Novel under Rajanikanta Bardoloi witnessed what it had to, the towering heights of social and psychological realism. Though Rajanikanta Bardoloi has contributions to other branches of literature, he is widely known as a great novelist. He had a reverence for the past and for Assam`s cultural and literary heritage, and was always inspired by a lofty idealism. His novels aim at rousing a regard for the rich heritage of Assam. He held up high moral standards before people, and for numan weakness he had the largest sympathies. Equally disposed to all classes of people, he assayed a Comedie Humaine, darting like a traveller from one swarming city or countryside to another with an abundance of human sympathy. He believed that life after all is one and that mutual regard would not cost anything and would remove unhappiness. Primal passions that ultimately count have their soil in every human heart and do not abide any distinctions of class or caste or community. He was thus the most large-hearted and the most felicitous of our novelists.

Contribution of Rajanikanta Bardoloi to Historical Novels

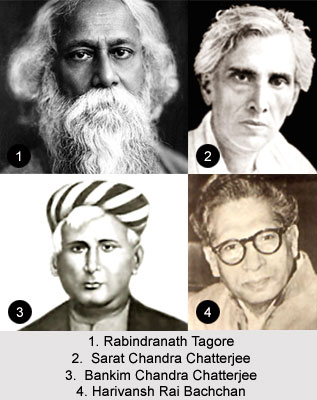

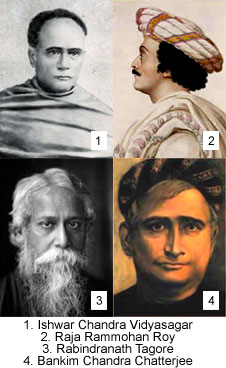

Influenced by Sir Walter Scott, and possessing the same pure relish for the charm of the wayside, the same ringing humour and infectious vivacity as of Scott and the great Bengali novelist, Bankimchandra, Bardoloi took up his pen to portray the history and social conditions of a critical period of Assamese national existence, and the work he produced endures for its depth of philosophic comment, descriptive power, fidelity to life, creative imagination and charm of style The Mirijiyari, written in 1895, is his first novel. It deals with the sad love-affair of two young Miris, and is obviously the first Assamese novel on tribal life. Monomoti (1900) is Bardoloi`s best work. Placed against the background of the declining years of Ahom Rule and the Burmese invasion of Assam, the consequent insecurity and unrest both social and political; the novel deals with the love story of Laksmikanta and Monomoti. The heroism of Laksmikanta and the womanly dignity of Monomoti are both brought into bold relief, and they haunt our memories. If we may quote an English poet, blessings and prayers in nobler retinue than sceptred king or laurelled conqueror knows, follow these lovers. Rangill (1925) has the same dark historical background. Against the Burmese invasion, social and political chaos and court intrigues, the character of an ideal woman sheds its divine and redeeming brilliance. The good and distinguished lady Rahgili has her earthly love, but this love is gradually sublimated to divine love. The novelist suggests that the fortitude and nobility of Rangill is no mere casual feature of a single and noble household, but that suffering like hers is characteristic of the time and symptomatic of the decadence of society.

Another historical novel is Rahdai Ligiri (Rahdai the Courtmaid), depicting the ideal of pure love. Rahdai, a simple maiden, is in deep love with Dayaram, also an ordinary youth. The pure flame of Rahdai`s innocent and profound love for Dayaram burns steadily even in the midst of blinding and overpowering storms of royal displeasure, privations, and temptations. When tyranny becomes oppressive, she takes to yoga and thereby not only saves herself but also changes the mind of Dayaram. Nirmal Bhakat (1925) describes how Nirmal is taken captive by the Burmese during their second invasion of Assam, and how, after a long exile in Burma, he returned home to find that not only the country but also his own home has changed enormously and that his wife has married another man. Nirmal does not despair of life. He becomes a Vaisnavite devotee and spends the rest of his life in religious peace, whereby, according to the Upanishadic Seer, "what has not been heard of becomes heard of, what has not been thought of becomes thought of, what has not been understood becomes understood."

Historical in setting and with marked topographical lining, the Tamresvari Mandir (The Shrine of Goddess Tamresvari) tells the story of a passionate pair-Dhaneswar and Aghoni-whose union is crossed by several factors, the greatest being the sentient Tantricism of the temple itself. The longdelayed union is finally affected by the victory of Vaisnavism over Tantricism, of all-embracing love over blind ritual. The events belong approximately to the same time as those of Nirmal Bhakat.

Historical in setting and with marked topographical lining, the Tamresvari Mandir (The Shrine of Goddess Tamresvari) tells the story of a passionate pair-Dhaneswar and Aghoni-whose union is crossed by several factors, the greatest being the sentient Tantricism of the temple itself. The longdelayed union is finally affected by the victory of Vaisnavism over Tantricism, of all-embracing love over blind ritual. The events belong approximately to the same time as those of Nirmal Bhakat.

The Danduva Droh. (1919) deals with the revolt of the people of Kamrup against the Ahom rule. Provoked by the misrule and oppression of the Ahom Viceroy, Badan Chandra, at Gauhati, the Kamrup people revolt under the leadership of the two heroic brothers, Hardatta and Birdatta. In the battles that follow, Birdatta dies fighting, Hardatta is captured and court-martialled, and Hardatta`s daughter kills herself by jumping into the river Brahmaputra to evade captivity. The introduction of love stories enlivens narratives which are laden with the history of Assam around 1800. Radha-Rukmini is yet another historical novel of Rajanikanta Bardoloi`s. It deals with the revolt of the Mowamaria sect of Vaisnavites against the Ahom rule, which broke out towards the middle of the 18th century. The novel narrates the heroic exploits of two Mowamaria heroines-Radha and Rukmini. Though historical in atmosphere, Bardoloi`s novels do not aim so much at recreating history as at imaginatively depicting the life of men and women. In doing this he has achieved no mean success. Bardoloi`s female characters possess special charm. The love, fidelity, tenderness, mental resourcefulness, resolution and extraordinary courage they display in the face of heavy odds, make his women admirable. Yet the novelist does not show a great inclination to draw their full portraits. He gives, on the other hand, much consideration to plot-construction, to unusual sensational incidents and thrilling action which in its variety is like a rich tapestry. Perhaps one thing more should be said of Bardoloi`s novels and that is that they exhibit the goodness, beauty, and moral strength of human life. The novelist further betrays a predilection for Tantricism and Vaisnavism, and in elucidating Tantric culture, he seems to have been influenced by Bankim Chatterjee. The plots are ingeniously conceived no doubt; but the writer does not hesitate to draw in upon the beliefs of people including those related to the shadowy deeps of the occult. Social reform is the aim of two of Dandinath Kalita`s novels Sadhand and Abiskar. The leading characters of both, Dinabandhu and Madhava, sacrifice all personal happiness at the altar of social purification. In the two women, Rambha and Pratima, the novelist depicts the problem of fallen women and suggests its solution. Both the novels reflect the social conscience of the tirelessly dialectical novelist and hold up for criticism and analysis social injustices and parochialism. The third novel, Ganaviplav (The Revolution of the Masses) depicts the Mowamaria revolution which broke out towards the close of the Ahom Rule in Assam. There is a faithful reproduction of history, set forth in simple, graphic episodes, but there is not much of creative imagination in characterisation in this novel. There is the same lack of fertile imagination that marks his long poem, Asam Sandhya. Kalita is a realist in his faithfulness to the surface; but he is never concerned with nuances of character and situation that spring from awareness of the growth of the human mind in response to critical stimuli.