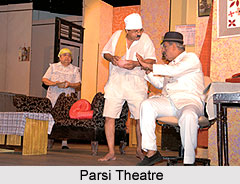

About Parsi Theatre

Parsi theatre was highly influential in 1850s and 1930s. Parsi theatre can be seen as India`s first modern commercial theatre. It was an aggregate of European techniques, pageantry, and local forms, enormously successful in the subcontinent. As the name indicates, it was subsidized to a great extent by Parsis. Parsis were mainly engaged in trading and shipbuilding. They eventually became an important business force on the west coast by the early nineteenth century, and began to cultivate the arts and philanthropy. A Parsi, Sir Jamsetjee Jeejeebhoy, bought the colonial Bombay Theatre in 1835. In 1846 the Grant Road Theatre in Bombay, constructed by Jagannath Sunkersett began hosting plays in English, then in Marathi, Gujarati, and Urdu or Hindi.

The first Parsi production is normally dated to October 1853, by the Parsee Stage Players at Grant Road Theatre. Beginning as amateur groups that soon turned professional, many new troupes were launched in this period of rapid expansion when audiences grew large, made up mostly of Bombay`s middle class. Major ones included the Parsee Stage Players, Victoria Theatrical Company, Elphinstone Dramatic Club, Zoroastrian Theatrical Club, Alfred Theatrical Company, Madan Theatres in Calcutta, Empress Victoria Theatrical Company and Shakespeare Natak Mandali. By the 1890s, they employed salaried dramatists and actors. They built their own playhouses, and printed their scripts. They may have had many Parsi financiers, managers, performers, and patrons. But the personnel were by no means exclusively Parsi. Considerable cross-regional and cross-linguistic movement of artists and writers led to a heterogeneous mix at a broadly national level, with the result that Parsi companies not only worked in Gujarati, Urdu, Hindi, and even English, but inspired theatres in virtually every corner of India. This created perhaps the largest ticket-buying audience in Indian stage history. By 1900, troupes had started in Karachi, Lahore, Jodhpur, Agra, Aligarh, Meerut, Lucknow, and Hyderabad. Although Parsi theatre survived till the 1940s and beyond, notably with Fida Hussain in Calcutta, after the 1920s a majority of the companies transformed into movie studios once the Indian cinema industry was inaugurated. Later, with the coming of the talkies i.e. Alam Ara in 1931, most of them either closed down or grew into larger units. But one way or another, Parsi capital sustained at least three major studios namely Imperial Film, Minerva Movietone, Wadia Movietone and one distribution network, the Madan Theatres.

The form was highly eclectic and of unlike parts, taking stories from the Persian legendary Shahnama, the Sanskrit epic Mahabharata, the fabulous Arabic Arabian Nights, Shakespeare`s tragedies and comedies, and Victorian melodrama, etc. Its style came from all of the above as well as English amateur theatricals, British touring repertories, European realistic narrative structures, the singing and performing traditions of nineteenth-century Indian courtesans, and the visual regime of Indian painter Raja Ravi Varma. The combination of simple plot, clearly delineated characters, strong emotional values, spectacle, and moral tone made the plays enormously popular. The mythological genre principally implied Hindu myths, and might therefore be called Puranic as well.

It became a heavily complicated ideological site, marking off linguistic territorialities, for example Hindi from Urdu or Hindustani, and partitioning the cultural apparatus of one language from another, especially as in the drama of Radheshyam Kathavachak and Narayan Prasad Betab. The mythological drama can also be read as a familiar and resilient inventory of figures in shorthand adopted to reflect urgent concerns. According to Ashish Rajadhyaksha and Paul Willemen, the `invocation of myths is less important than the way the stories are treated as a genre, modified as narratives or formally deployed as allegorical relays`, dovetailing the mythological with the `conservatively constructed notion of the social`.

The social drama was equally popular. It shaded into melodrama when propelled less by story and more by emotional effects, but its issues were mostly elaborated within the family. Problems about equality, sexuality, education, and inheritance enacted within domestic terms. It might also be seen as melodrama in a twentieth-century milieu, extending melodrama by introducing pressures of modernization. In telling stories with reformist concerns such as the rehabilitation of young widows, alcohol abuse, female literacy, sectarianism, polygamy, Westernization, and the anxiety of determining national and regional identities, writers like Agha Hashr Kashmiri, Betab, and Kathavachak depicted a broader landscape than just a domestic one.

Famous Parsi plays, covering the range from romance to mythological and social, include Indarsabha or `Indra`s Court``, Gul Bakavali or `Bakavali`s Flower`, Laila-Majnun or `Laila and Majnun`, and Shirin-Farhad i.e. `Shirin and Farhad` in numerous versions were very famous. Some others can be mentioned as Hashr`s Yahndi ki ladki or `Jew`s Daughter` in 1913 and Rustam aur Sohrab or `Rustam and Sohrab` in 1929, Betab`s Mahabharat in 1913, Ramayan in 1915, Kumari Kimiari or `Kinnari Girl` in 1928 and Hamari bhul or `Our Mistake` in 1937 and Kathavachak`s Vir Abhimanyu i.e. `Heroic Abhimanyu` in 1914, Shravan Kumar in 1916, and Bharatmata i.e. `Mother India` in 1918. The several Shakespearean adaptations included Ahsan`s Khun-e-nahaq or `Unjustified Murder` in 1898, from Hamlet, Shahid-e-wafa or `Martyr to Constancy` in 1898, from Othello, and Dilfarosh i.e. `Merchant of Hearts` in 1900, from Merchant of Venice were also staged. Hashr`s Safed khun i.e. `White Blood` in 1906, from King Lear, and Betab`s Gorakhdhanda i.e. `Labyrinth` in 1909, from Comedy of Errors.

The performing conditions of the new configuration marked a significant change in viewing habits, enduringly because the proscenium arch, brought to India by the British in the 1750s and elaborated afterwards. This is replaced the open arena that had been the most prevalent site up to this time. The closed space that supplanted it was often roughly made with tin and bamboo or architecturally constructed with brick and mortar. Inside, there was elaborate stage tricks incorporated into the performance. The proscenium was pushed back a fair distance from the spectators, with an orchestra pit, usually dug into the earth where the platform ended, between it and the audience. The time of performance was generally late evening.

Plays ran for weeks, even years depending on their popularity, and went on tour sometimes for months together covering India, but also Burma, Ceylon, Malaya, Indonesia, and parts of Africa. Because it encouraged new mimetic prospects, connected to the picture frame, and to the possibilities of reproducing perspectival space, the proscenium arch was by far the most significant adaptation of Western conventions that the Parsi theatre appropriated. It achieved mimesis, or verisimilitude, through backcloths painted on the principles of optical convergence or perspectival illusion. Images receded into the distant upstage and created a fiction of reality since the paintings were governed by the notion of the central vanishing point. The `locations` appeared more real than anything produced previously. Generalized backdrops included forest, garden, street, palace, and sometimes heaven. Besides, each company had its specific curtain, its legend of sorts. The Zoroastrian Club displayed King Ushtaspa`s court, with Zarathustra holding the mythical ball of fire. At first, Europeans created the `drops` but later, Indian painters trained at art colleges. The Painter brothers were the best-known backdrop artists.

Parsi theatre as well as Sangitnatak and early movies employed Ravi Varma`s mise-en-scene. He drew historical, mythological, and modern figures in the foreground, and a dense environment behind contextualized, or provided the attendant conditions or given circumstances for, their behaviour. Scene designers imitated this way of describing locale, of demarcating background from foreground, accommodating the actors` postures and gestures into it. The backdrops manifested locations analogous to those summoned by the text, and therefore interpolated the performers into physically defined. But they also offered a spectacular and fantastic space beyond the illusionistic one. While the narrative was grounded in the atmosphere produced by the materiality of the paintings and the architecture that enclosed them, paradoxically the world of romance and dream was also revealed and made possible through this very tangibility.

Since the backcloths were framed in the proscenium arch as in a window. For the viewer, there appeared to be a continuity of space and time. Some sort of space or the preceding part of the locale i.e. the palace, forest, street is existed before it came into sight. One portion existed in the arch and another beyond the arch. This continuum resembled the way we experience time and space in ordinary life. Events follow one another, the arrow of time flies toward the future. This was new for the spectators, or at least unlike what they encountered in pre-modem theatrical forms. Thus the curtains allowed new means to tell a story, perceive dramatic continuity, and create character formations. Hafiz Abdullah`s Sakhawat Khudaost Badshah or `Generous and Godly Emperor` in 1890 for the Indian Imperial Theatrical company had fourteen backdrops. The scenes delineated became increasingly more `real` or illusionist.

The Parsi theatre appropriated other Western presentational modes that produced formal and experiential mutations. It assimilated the five-act structure, related by extension to the proscenium that put the chronological narrative into place in the first instance. It rearranged the cognizance of stage time and space by intervening in the conventions of formality in Indian theatric and visual traditions. The mechanical devices to operate flying figures and furniture, imported directly from melodramas in London. This shaped the textual scenarios.

The melodramatic style occasioned by stage machinery became so popular that, in a sense, conventional storytelling was redrafted. By definition, melodrama integrates spoken text with music. The category now also came to be applied to romantic plots that act on the audience`s emotions without considering character elaboration or logic. An economically workable commercial stage in most urban centres fitted folk performance to the European proscenium, creating technical models and unexpected marvels. Eventually, and paradoxically, these were put in the service of realism as being assembled at this time. Architectural and stage technologies allowed for vampire pits, flying beds, miraculous appearances and disappearances. These are best suited for romances and mythological tales.

Among the most popular actors of the Parsi stage there were Dadabhai Patel, K. N. Kabraji, Jehangir Khambata, Cowasji Khatao, C. S. Nazir, Khurshedji Balliwala, Framji Appu, Sohrabji Oghra, Abdul Rahman Kabali, Sohrab Modi, Amrit Keshav Nayak, and Fida Hussain. Among the famous actresses, Mary Fenton or Mehrbai was the daughter of an English officer in the British Indian army. Gohar or Kayoum Mamajiwala debuted as a child, and Patience Cooper and Seeta Devi performed with Madan Theatres in Calcutta. The light-classical musical vocabulary of Parsi theatre included ghazal, qawwali, thumri, dadra, and hori. The common instruments were harmonium or `organ`, clarinet, sarangi, tabla, and nakkara drums.

Repertoire of Parsi Theatre

Repertoire of Parsi Theatre depicts the best variation in the theatre culture. With the proliferation of Urdu theatre, Indo-Muslim manners and messages, vestiges of feudal privilege became embedded in the North Indian theatrical vocabulary. Yet the court, as a social institution, had collapsed and the means of sustaining dramatic activity became concentrated instead in the economic networks for entertainment developing in the cities.

Repertoire of Parsi Theatre depicts the best variation in the theatre culture. With the proliferation of Urdu theatre, Indo-Muslim manners and messages, vestiges of feudal privilege became embedded in the North Indian theatrical vocabulary. Yet the court, as a social institution, had collapsed and the means of sustaining dramatic activity became concentrated instead in the economic networks for entertainment developing in the cities.

Foremost among these was the so-called Parsi stage, a broadbased commercial theatre whose appeal and influence extended far beyond the ethnic group from which it took its name. In a short time the demand for Parsi theatrical fare spread to all parts of India. The major companies routinely toured between Mumbai, Lahore, Karachi, Peshawar, Delhi and the Indo Gangetic plain, Kolkata and Chennai. Parsi shows were the primary form of dramatic entertainment consistently available to urban audiences in greater India for almost a century. In consequence, the influence wrought by this stage on the development of modern drama and theatrical practice, and on the folk styles of performance, has been substantial. The Parsi theatre stage exerted a major impact on the emerging Marathi theatre and Gujarati theatres, as well as on new drama in Hindi language, Bengali language, Tamil language, and other regional languages.

Much of the initial inspiration for the Parsi stage came from British-sponsored dramatic efforts in their colony. English style playhouses were erected in Mumbai and Kolkata in the late eighteenth century, and the native elite was invited to attend English-produced performances from time to time and even to act in selected roles. Later the Parsi companies played in the same halls and took over the material culture of European theatre: the proscenium arch with its backdrop and curtains, Western furniture and other props, costumes, and a variety of mechanical devices for staging special effects. Artists from Europe were commissioned to paint the scenery, and the latest in "elaborate appliances" were regularly ordered from England, so as to achieve "the wonderful stage effects of storms, seas or rivers in commotion, castles, sieges, steamers, aerial movements and the like."

The early playwrights of the Parsi stage, K. N. Kavraji, E. J. Khori, and N. R. Ranina, were themselves Parsis. Gujarati being their mother tongue, it became the first language of the Parsi theatre. By the 1870s the large companies had adopted the practice of hiring Muslim munshis (scribes) as part of their permanent staff, and Urdu language became the principal language of the stage.

In important respects aside from language, the Parsi theatre revealed its distinctive Indian character: it employed Indian subject matter and included a great deal of music and dance. These characteristics were a natural legacy of the Indian dramatic tradition; the existing folk drama much influenced the Parsi theatre while it exerted a counter effect on indigenous theatre.

The Parsi theatre`s sizable repertoire of mythological and legendary plays thus drew on the same stratum of North Indian popular culture as the nineteenth-century folk theatre and with equal alacrity embraced non-Indian subject matter side by side. Shakespeare provided a rich store of plots, and the prestige of the bard`s name went unsurpassed on the Parsi stage. The Shakespearean stories were heavily Indianized, characters being reassigned names, castes, and communities, geographical settings transferred to Asia, and motivations and story lines adjusted to fit the Indo-Muslim environment.

The music and dance of Parsi theatre, although difficult to document, appear to have been liberal in measure and hybrid in manner. The "orchestra" often consisted of harmonium and tabla, played by accompanists who, seated in the wings or pit, "also in many cases do duty as prompters."

Available scripts show that a typical scene in a Parsi stage play consisted of a variety of songs and verses (in forms such as thumri, ghazal, Iavani, sher, musaddas, mukhammas, savaiyd, or simply gana) connected by prose dialogues. In early plays, dialogues were composed in rhymed metrical lines; actors spoke them with great emphasis to project the lines to the back of the hall. Later prose became predominant, although rhyme at the end of sentences remained. In such stylistic matters much mutual influence is visible between the North Indian folk theatre forms such as Swang and the Parsi theatre in this period.

Although the Indian elite saw in the Parsi theatre vulgarity, sensationalism, and lack of aesthetic standards, the humbler sections of society thrilled to the mystique of English company names like the Corinthian, the Victoria, and the New Alfred. The sumptuous fittings of the Parsi stage, replete with elaborate painted scenery, fine costumes, exotic Anglo-Indian actresses, and tricks of stagecraft augmented the allure. Such shows may have been commonplace in the numerous theatrical houses of the big cities, but in the provincial towns the spectacles no doubt overawed the populace. No wonder then that the Bombay companies were eagerly sought as the purveyors of all that was current and stylish in theatre. They were widely emulated wherever they performed, particularly in the cities of Indian state of Uttar Pradesh such as Varanasi, Lucknow, and Kanpur where they enjoyed an enthusiastic following.

The exchange between the urban Parsi theatre and the simpler, more rustic Swang and Nautanki operated in both directions. Stories, songs, and stage techniques moved back and forth at different times. Early on, the Parsi theatre drew from the themes and conventions of the folk theatre. A common core of stories is found in both theatres in the period from 1850 to 1900. Once the Parsi theatre`s popularity was established, this process reversed itself.

Parsi Theatre in English

Parsi theatre in English was quite popular among the educated Parsis in Mumbai during the days of the British colonial rule in the country. The Parsis were among the elites in Mumbai and they became attracted to theatre by way of their interactions with the Europeans and local mercantile communities. Leading Indians were invited to the English theatre in return for hosting their colleagues at entertainments such as Nautch parties. By 1821, Parsis had begun attending the English-language Bombay Theatre (also known as the Theatre on the Green) located in the heart of the Fort area of south Bombay. In 1853 the theatre was shut down due to certain financial problems. It was sold to Jamshed Jejeebhoy.

Jamshed Jejeebhoy, along with Jagannath Shankarseth and Framji Cowasji, started collecting subscriptions and petitioned the Governor of Bombay for a new theatre. The Grant Road Theatre was opened in 1846 on land donated by Shankarseth with a generous contribution from Jejeebhoy. Until 1853 all performances in the Grant Road Theatre were in English. The performers of English theatre included both amateur British actors residing in the cantonment and civil lines and professional touring artists from England, Europe and America. Indian performers came onstage very rarely and that too as extras.

The first Parsi theatrical company appeared on the boards in 1853 with Rustom Zabooli and Sohrab, probably in Gujarati. Over the next few years, as the popularity of English theatre began to wane, Parsi and Hindu companies performing in Gujarati, Hindustani and Marathi found favour with the populations living in the Grant Road area. As these trends continued through the 1850s and 60s, full-length plays in Gujarati dominated, accompanied by shorter farces in Hindustani. Even in its earliest years, the Parsi theatre developed a penchant for producing plays based on Shakespeare. According to the newspapers, Parsi theatre productions of Taming of the Shrew, The Merchant of Venice, Two Gentlemen of Verona and Timon of Athens all mediated through the Gujarati language were mounted at the Grant Road Theatre between 1857 and 1859.

Concrete evidence of Indians performing in English appears from the early 1860s. The impetus fro this came from the students and ex-students of Elphinstone College. In 1861 a student named Kunvarji Nazir formed the Parsi Elphinstone Dramatic Society, an amateur club where enthusiasts received training from professionals like Hamilton Jacob. They staged a number of English plays at the Grant Road Theatre and earned respect from both Indian and European audiences. A few professors organised another student group, the Shakespeare Society, which put up productions in the private confines of the college once or twice a year. However, the trend of performing in English was noted only among the college. The vogue for performing in English was largely limited to the college, however. The desire to enact Shakespeare in English had given way by the late 1860s to an interest in adapting Shakespeare to Indian languages and environments. The professional company that succeeded the Elphinstone amateur group, the Elphinstone Theatrical Company or Elphinstone Natak Mandali, was primarily performing in Gujarati and Urdu by the early 1870s.

Parsi Theatre in Gujarati

Parsi theatre in Gujarati was the result of a slow but gradual shift from English theatrical performances. This turn towards the Gujarati Language, and gradually Urdu, was not merely an attempt to capture a larger audience. Strong nationalist sentiments can be seen in this embracing of a regional language. Shortly after Dadabhai Naoroji coined the term `Swadeshi` to counter colonial economic policy, Gujarati dramatists utilised the expression and spoke of need to construct a theatre that addressed their own people.

Parsi theatre in Gujarati was the result of a slow but gradual shift from English theatrical performances. This turn towards the Gujarati Language, and gradually Urdu, was not merely an attempt to capture a larger audience. Strong nationalist sentiments can be seen in this embracing of a regional language. Shortly after Dadabhai Naoroji coined the term `Swadeshi` to counter colonial economic policy, Gujarati dramatists utilised the expression and spoke of need to construct a theatre that addressed their own people.

In the preface to his first play, Bejan ane Manijeh (1869), Kaikhushro Navroji Kabra, the eminent journalist, explained that his goal was to compose Swadeshi plays for his Deshi brothers. As regards the sources that would constitute the content of these plays, an inexhaustible source was present. According to Kabra, and many of the other dramatists of the time, just as the West had its Homer and Shakespeare, so the East had its Kalidasa and Firdausi. Thus by recognising these influences, Kabra established the objective of the creation of cultural and historical consciousness through the plays, rather than mere pursuit of profit. The project here was that of re-inventing the past in the face of increasing colonial domination. A major influence during this time was the works of Firdausi, the narratives of the ancient Kings of the Parsis, of the kings of Persia. Thus Kabra very strongly focused on the Parsis as the historical community descended from Firdausi`s heroes. His objective in writing plays was to safeguard Parsi drama while reviving Parsi self-awareness and creating solidarity.

Kabra`s embrace of Firdausi and the Persian past was a continuation of the dramatic traditions among the Parsis. The earliest Parsi theatrical group had performed Rustom and Sohrab in several instalments in 1853 and 1854. Subsequently, Barjor and King Afrasiab and Rustom Pehlvan strengthened the identification between `Parsi theatre` as a new form of cultural expression and the mythological-history of the Persian homeland. Shahnama stories were already circulating as printed episodes (namas) in Gujarati and Persian. Oral recitations of the Shahnama were both a form of entertainment and tool for moral instruction in vernacular schools.

Kabra`s embrace of Firdausi and the Persian past was a continuation of the dramatic traditions among the Parsis. The earliest Parsi theatrical group had performed Rustom and Sohrab in several instalments in 1853 and 1854. Subsequently, Barjor and King Afrasiab and Rustom Pehlvan strengthened the identification between `Parsi theatre` as a new form of cultural expression and the mythological-history of the Persian homeland. Shahnama stories were already circulating as printed episodes (namas) in Gujarati and Persian. Oral recitations of the Shahnama were both a form of entertainment and tool for moral instruction in vernacular schools.

Through the Shahnama plays enacted in Gujarati, the `Parsi theatre` was thus established in the early years as a public representation of a particular community. Though these plays were not meant exclusively for the Parsis, they nonetheless expressed a celebration of Parsi identity. Gujarati-language media such as folksongs and tales were often used to propagate reformist beliefs, as well as to inculcate new behaviour and attitudes, especially among women. Women were seen as particularly vulnerable to superstitions, and their domestic seclusion and low degree of educational attainment were blamed on the surrounding non-Parsi society. In popular songs and stories the female heroes of the Shahnama and medieval Persian romances, such as Nizami`s, were upheld as models.

In addition to the Nama stories and their enactments, the Garbas and Garbi`s, or women`s songs, and the old Dastans and Qissas, Parsi popular culture at mid-century included important genres such as the Khayals or improvised poems of the Turra-Kalgi factions, playlets and songs from the Gujarati dramatic form Bhavai, the Lavanis and ballads in Gujarati and Marathi associated with the Maharis and Tamasha, as well as ghazals in Persian, Urdu, and Gujarati, songs based on Bhakti poets like Kabir, and Boris, Thumris, Tappas and other secular songs. These genres are all exemplified in the numerous song anthologies compiled by Parsis and printed in Gujarati in this period.

These songs from a variety of languages, published in the Gujarati script, in turn became a resource for the playwrights of the Parsi theatre. Playwrights sometimes commissioned songs for their plays from well-known poets, and their names are mentioned in the prefaces. But equally they drew on popular tunes, setting new words to a popular song and borrowing freely from existing material. Songs were necessary adjuncts to narratives in creating stage appeal, and the importance of music grew as the Parsi theatre developed.

Parsi Theatre in Urdu

Parsi theatre in Urdu was an outcome of the people`s inclinations towards high status art forms. There was seen an increasing passion for song, poetry and sweet speech at this time in Parsi theatre, all of which were fulfilled by the Urdu language. This popularisation of the Urdu language was pioneered by a highly educated Parsi theatrical personality, Dadabhai Sorabji Patel. Dadi Patel M.A., as he was popularly known, was from a wealthy commercial family and one of the first Parsis to receive a Master of Arts degree from the University of Bombay. He made an immense contribution towards PArsi theatre. Not only did he commission the first Urdu drama, he also popularised `opera` as a new form, introduced `scientific` stagecraft, professionalised the company by offering full-time salaries and began the practice of touring even before railway lines were completed to the Deccan. When he became the president of the Victoria Theatrical Company in 1869, he managed to steer it in a new direction.

Writers of Parsi Theatre in Urdu

The first Urdu play was Sone ke mol ki Khurshed, a translation by Behram Fardun Marzban of a Gujarati drama by Edalji Khori. It was commissioned for the Victoria Theatrical Company by Dadi Patel in 1871. The writer made two claims for using Urdu language. One was that the language stretched beyond specific communities and therefore increased the audience for Parsi Theatre. Also, it enhanced the literary status of theatre by connecting it to rich narrative and lyric traditions. This play, along with other Urdu dramas of the time, had the peculiarity of being printed in the Gujarati script. The Arabic script only began to be used for printed Urdu plays a decade later. The Gujarati script reveals the lack of literacy in Urdu among the public who bought and used these plays. The next Urdu translator/playwright, who was also a Parsi and a non-native speaker of Urdu, was Aram. Aram left three Gujarati prefaces, a good indicator that his readers were literate in Gujarati.

Mahmud Miyan `Raunaq`, was the next Urdu playwright of accord. He was a prolific writer for the Victoria Company in the 1870`s and 1880`s. He was the first non-Parsi to write dramas for the Parsi theatre. Although Raunaq`s plays too were printed in Urdu in the Gujarati script, he claimed great concern for the Makhraj of the Urdu language. Makhraj is a term meaning both `pronunciation` and `etymology`.

The next generation of Urdu dramatists, who published plays in the 1880s, were different from the earlier writers in that they hailed from Uttar Pradesh and were Muslims trained in the classical languages from which Urdu developed. Karimuddin Murad was born in Bareli and was educated in Arabic and Persian, where he later taught in a local Madrasa. Amanullah Khan `Habab` came from Fatehpur, where he was a court poet in the service of the Nawabs of Rampur and Rewan in the 1870s. He began writing plays for the Parsi theatre in 1881. Hafiz Muhammad Abdullah like Habab was from Fatehpur educated in Arabic and Persian and was a hafiz-i quran (protector of the Holy Quran, one who has the entire book by heart).

Works of Parsi Theatre in Urdu

These early plays in Urdu used a number of different narrative traditions apart from the Gujarati plays of the period. Most of them are original in the sense of being made up afresh although from familiar elements. In Sone ke molki Khurshed, Fateh Shah becomes displeased with his queen of seven years and offers her for sale at a public auction, stipulating that whoever can fill a one-cubic yard pit with gold will get her hand. The merchant Firoz arrives in the `harbour` of Delhi and eventually wins her. Nurjahan, despite the title, is not a Mughal historical drama, but concerns a tyrant, Zalim Singh, who kidnaps two princesses who are eventually rescued by the hero Muhabat Khan. The intercession of jinns and fairies is essential to the plot. The story of Hatim, known from dastans, is about a princess who poses seven questions that must be answered by a single man. In search of the answers, Hatim encounters various supernatural forces, giving the theatre company an opportunity to display its special stage effects. Jahangir Shah involves a conflict between two imaginary kings; the memorable scenes are those of Jahangir arriving in a grotto through a tunnel and the witty repartee between the king`s cook and a young woman planning an assignation with her lover. The stuff of these dramas can be said to consist of the persecution and rescue of desirable women, the magical interference of supernatural beings, and the struggles of the hero caught between the two, all familiar elements from the universe of Persian and Urdu Dastans.

The audience received this turn towards Urdu well, though newspaper reviews of this early time comment on the audience`s surprise in hearing Parsi actors enunciate the words of the Urdu language. The adoption of Urdu in Parsi theatre, thus it is seen, was not merely a move to capture a larger audience. It was also largely favoured on aesthetic grounds, and the beauty and advantage of its use in poetry and song.