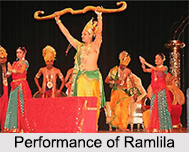

Music for outdoor stage forms an important part as, until very recently, shows were performed outdoors mainly at night - on temporarily erected stages or platforms, on porches in market areas, in courtyards, or in tented arenas at fairs. Three sides of the stage were generally open to the public, and large crowd gathered, as many as ten thousand spectators by some accounts.

Music for outdoor stage forms an important part as, until very recently, shows were performed outdoors mainly at night - on temporarily erected stages or platforms, on porches in market areas, in courtyards, or in tented arenas at fairs. Three sides of the stage were generally open to the public, and large crowd gathered, as many as ten thousand spectators by some accounts.

In the absence of electricity and amplification, the foremost demand was that the music and voices of actor-singers be audible. Hearing was even more important than seeing, because sightlines would have been obstructed for many in the throng. Probably for these reasons, Nautanki, like other traditional theatres favoured instruments with piercing timbres. The core of the Nautanki ensemble consisted of a high-pitched reed instrument, such as the indigenous Shehnai, a relative of the oboe, or later the imported clarinet.

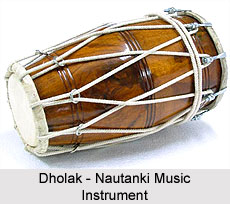

Rhythm was maintained by the booming Nagara, a kettledrum played with sticks, supported by a second higher-pitched dholak, a popular double-faced hand-drum. The shehnai and nagard were traditionally part of a processional ensemble known as the naubat, whose role was to lead military parades and announce the watches of the day in royal palaces. As used in Nautanki theatre, the naubat served first in its original function as marching band. It announced the show, playing in procession in the town or village beforehand and at the commencement of the evening`s entertainment while the audience was assembling. Second, it served as "orchestra," accompanying the singers during the drama. Even today, the loud, rapid-fire drumming of the nagara sums up the heroic and martial character of Nautanki and serves as its ubiquitous trademark. The thin piping tone of the Shehnai, by contrast, alerts the listener to the romantic and feminine side of the theatre, signalling in particular the flirtatious games of the dancer-actress.

As with the instruments, the singing of the actors had to be very loud to project to the crowds. To reach this goal they cultivated an open-throated, forceful vocal style, dwelling primarily in the upper register. The recitatives of Nautanki typically begin on the tonic in the upper octave and wind their way gradually downward to close on the lower tonic. The melodic "shadow" provided by the accompanying instrument anticipates the beginning, leading up to the high tonic at the end of the preceding phrase. Holding the breath on high notes is considered a feat of virtuosity, earning outbursts of praise from the audiªence.5 At climactic moments, the singer conveys dramatic bursts of emotion by exploring the uppermost notes in his or her register; they are the ones most likely to cut through the ambient noise in the performance area and make at: impact on the listeners. Male singers, specially female impersonators, may employ a falsetto voice quality. The most virtuosic Nautanki singing is characterized by stirring florid passages charged with an almost erotic excess, an operatic overflow of passion.

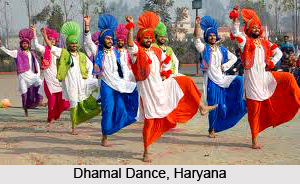

Rapid ornamental turns, melismatic ascents and descents, and other flourishes are used to adorn the vocal line and are much prized. The vibrato effects common to choral Sufi singing (Qawali) and the folk singing of Haryana, Rajasthan, or the Punjab are usually absent. The particular musical interaction that occurs between the singer-actors and the instrumental ensemble in Nautanki reflects the demands of communication in an outdoor setting. Three types of poetic discourse characterize Nautanki`s sung text: these are narrative, dialogue, and lyric. Prose passages may also be introduced into the verbal texture but are never sung. Narrative and dialogue carry the forward movement of the story and must be clearly enunciated for audience comprehension. Perhaps for this reason, overlap between singers and instrumentalists in these sections is reduced to a minimum. The poetic lines are delivered one by one in recitative style, with percussion and the less audible melodic instruments entering after each line is concluded. These passages produce an antiphonal structure between the singer and the instrumental ensemble, the two alternating and taking turns throughout.

Rapid ornamental turns, melismatic ascents and descents, and other flourishes are used to adorn the vocal line and are much prized. The vibrato effects common to choral Sufi singing (Qawali) and the folk singing of Haryana, Rajasthan, or the Punjab are usually absent. The particular musical interaction that occurs between the singer-actors and the instrumental ensemble in Nautanki reflects the demands of communication in an outdoor setting. Three types of poetic discourse characterize Nautanki`s sung text: these are narrative, dialogue, and lyric. Prose passages may also be introduced into the verbal texture but are never sung. Narrative and dialogue carry the forward movement of the story and must be clearly enunciated for audience comprehension. Perhaps for this reason, overlap between singers and instrumentalists in these sections is reduced to a minimum. The poetic lines are delivered one by one in recitative style, with percussion and the less audible melodic instruments entering after each line is concluded. These passages produce an antiphonal structure between the singer and the instrumental ensemble, the two alternating and taking turns throughout.

During the recitative, the singer`s meter does not follow the framework of tala (rhythm cycle), as it would in Hindustani vocal music. He or she spontaneously matches the short and long weights of the metered line to the standard contours of the appropriate melody or freely improvises on an end rhyme using melismatic ornamentation. As soon as the singer finishes the line, and usually beginning with its last note, the percussion enters and plays a pattern in a regular rhythm cycle, ordinarily eight or sixteen beats. Melodic instruments such as shehnai, flute, clarinet, sarangi, or harmonium may shadow the singer during the recitative, lagging behind slightly and imitating the sung line. Customarily they repeat a refrain melody (comparable to the Lahara of classical music) during the percussion solos. This antiphonal style contrasts with the style of the lyric passages, which exhibits simultaneous accompaniment (Sath-Sangat). This style is found in the song forms of Nautanki such as Dadra, Thumri, and Ghazal.