Scales of East Indian folk music have a significant relevance to the north Indian music. The simple methods, scales and modes of North Indian system given here can be useful to understand musical contours, forms, hybrids, patterns, graces, combinations, attacking forms and so on. It is of course known that the melodic principles of performance rest on constant methods of shifting of one note to another. The various methods of shifting count much.

Scales of East Indian folk music have a significant relevance to the north Indian music. The simple methods, scales and modes of North Indian system given here can be useful to understand musical contours, forms, hybrids, patterns, graces, combinations, attacking forms and so on. It is of course known that the melodic principles of performance rest on constant methods of shifting of one note to another. The various methods of shifting count much.

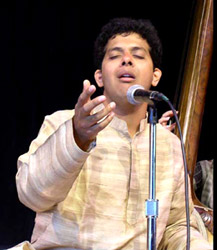

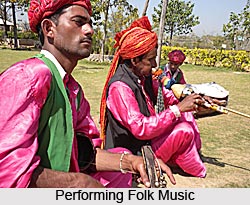

In the North Indian system, for instance, shifting is mostly carried by glide or glissando. Of course, there is little specific glide as a rule in folk-music and far less it is in tribal music, the movement from note to note being straight, coarse, direct, raucous and simple. The structural system of folk-music bears evidence of various applications of individual graces and peculiar combinations, because monophony, in this country, developed more or less on the basis of individual actions of singers. It will be seen that individual singers predominate in many cases and the community act as mere followers or repeaters. And the individuals determine the principal movement from one note to another based on modes which are now explained through technical terms, unknown to the rural or primitive world.

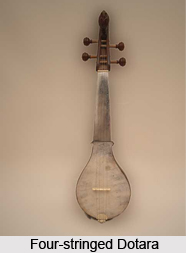

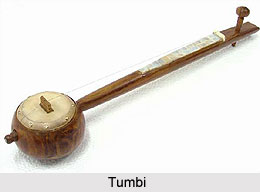

Even the seven notes, wherever these are used, signify to them nothing more than some relative sounds which occur in fixed phrases. The Indian names, sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni, if known to any rural folk-singer of present day, are nothing but names of notes, whatever may be the meaning of these terms. A Bhatiali singer or a singer of Baul tunes his chordophone, dotara (the three-stringer), in first-and-fourth note principle impulsively, and gets seven notes spontaneously. The idea of consonance system is inherent in folk-musicians of the modern age. A modern folk-singer often uses harmonium conveniently.

Even the seven notes, wherever these are used, signify to them nothing more than some relative sounds which occur in fixed phrases. The Indian names, sa-re-ga-ma-pa-dha-ni, if known to any rural folk-singer of present day, are nothing but names of notes, whatever may be the meaning of these terms. A Bhatiali singer or a singer of Baul tunes his chordophone, dotara (the three-stringer), in first-and-fourth note principle impulsively, and gets seven notes spontaneously. The idea of consonance system is inherent in folk-musicians of the modern age. A modern folk-singer often uses harmonium conveniently.

The seven notes along with five semitones make a complete Indian saptak, whereas in the western system the thirteenth note, that is, the eighth tone is calculated to make one octave complete. The positions of semitones, that is, the intervals and time divisions amongst notes, may now be explained through Indian method. This means that, though the arrangement of notes or steps looks like the arrangement of keys of the diatonic scale when the tonic Sa is fixed on it, the difference may be noted in the position of flat and sharp notes.

Sharp and flat notes, according to the Indian idea, are high and low respectively. In the North Indian system, and more in spontaneous use as in folk-songs, the same high and low (tones and semitones) in a scale are not used at the same time.

The selection of tonic by the folk-singer is made impulsively. The tonic may be fixed on any key (the second or the third, etc.). The note at once becomes home note of the scale, that is, the tonic Sa, which is dominant in folk-music. The position of other notes is determined according to the fixed-up Sa, that is, once the Sa of the singer is known to be fixed, it remains as a standing scale for further determinant of the mode. The scale of a primitive tune or folk-tune is detected from the fixation of the motive or the theme of music on the scale. As soon as the singer recites some phrases or notes, he repeats the motive; thus he follows a mode derived from elementary variations of notes.

The mode is generally named by musicologists after a raga, which indicates the steps and intervals between the notes used. Often some primitive tunes and folk-tunes are seen to be fragmentary. The singer is not conversant with the note or scale in the formal way. It is imbibed by the method of inheritance and habits formed through traditional oral recapitulation of phrases.

Primitive music and some folk-music of backward classes of India are confined to a few modes only, and they are too often partially utilized. The partial modes generally belong either to upper or to lower tetra chords. The use of upper or lower tetra chords generally depends on the ascending or descending order of music. Variations occur mostly in the use of lower tetra chord.

To get a mode, the seven notes are required to be linked up in ascending or descending order following the arrow one way. A mode emphasizes the same track in ascent and descent both ways, though slight variations may occur. Then, again, in addition to the first and the fifth, only one out of the two is used at a time (i.e., S, R or r, G or g, M or m, D or d, N or n). The semitone along with the tone has also sometimes a restricted use.

The simultaneous application of the adjacent note, tone-semitone-tone or major-minor-major corresponding to note-half note is not possible. The most important feature is the fact that the semitone, previous to the fifth, i.e., ma-sharp tivra-madhyama/F (in case C is the scale), hardly occurs in, or is never used in primitive and folk-music; and, therefore, modes with variations of tivra-madhyama needs no consideration here. Only a limited number of modes are in vogue in primitive music and folk-music. Numbers of tracks shown above by arrows crisscrossed are mentionable for classifying raga modes, out of which some selected steps numbering about ten are generally used for Northern Indian music.

A performance of spontaneous composition is prepared without knowledge of the grammar in practice, and, therefore, if a musical code is followed by the singer, it is a mere device developed automatically in course of practice and that too unknowingly. It is normal that music based on a track or mode has been current throughout the ages. The rural singer firmly clutches here the outline laid on that. If a classification of tune is made now, it is done only in a manner about which the singer must have been ignorant. Now, it is observed that five or six such modes are current to get clear classifications of primitive and folk-tunes taking C as the home-tone.

Though the top note, the eighth (tone) has not been mentioned at the end of each mode, the top note is of prime importance in some types of folk-music. These tracks and steps help in discussing the form and structure of musical analysis. The folk-singer is not theoretically conversant with all these. Neither notes nor notations are known to him. He is in the habit of using notes or groups of notes as required.

Anyway, the uses of six or seven degrees of functional scales, of reduced notes, of intervals, of extended notes, of curved use of notes as familiar in Indian ragas, of short touches, etc., are spontaneous practices. Most of these forms appear in developed folk songs of different types but separately. Speech-song helps the tune to make it a complete whole through peculiarities of repetition, articulation, ascents and descents, resting notes, bursting notes, attacking notes, yelling, rhythmic peculiarities, and juxtaposition of speech in tune and rhythm. All these may be considered separately.