Introduction

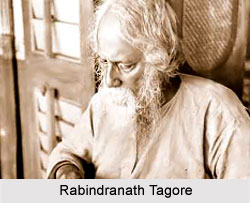

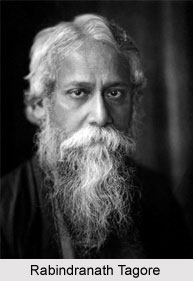

Rabindranath Tagore, a renowned poet and a Nobel award receiver for literature, was born in the year 1861. He grew up in the heart of Kolkata in a colonised country. Tagore`s works focused on certain issues such as racial humiliation, search for self-esteem, education, and religion that was concerned with India. Two songs from his Rabindra Sangeet canon are now the national anthems of Bangladesh and India, `Amar Shonar Bangla` and `Jana Gana Mana` respectively. Tagore was also a cultural reformer and polymath who modernised Bengali art by rejecting strictures, binding it to classical Indian forms. Literary works, nationalism and Santiniketan remained the passion of Tagore, for more than six decades of his life. Tagore breathed his last in the year 1941.

Rabindranath Tagore, a renowned poet and a Nobel award receiver for literature, was born in the year 1861. He grew up in the heart of Kolkata in a colonised country. Tagore`s works focused on certain issues such as racial humiliation, search for self-esteem, education, and religion that was concerned with India. Two songs from his Rabindra Sangeet canon are now the national anthems of Bangladesh and India, `Amar Shonar Bangla` and `Jana Gana Mana` respectively. Tagore was also a cultural reformer and polymath who modernised Bengali art by rejecting strictures, binding it to classical Indian forms. Literary works, nationalism and Santiniketan remained the passion of Tagore, for more than six decades of his life. Tagore breathed his last in the year 1941.

Early Life of Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore was born the youngest of fourteen children, in the Jorasanko mansion, now known as Tagore House, to parents Debendranath Tagore and Sarada Devi. Rabindranath Tagore was born in a family that could easily be passed off as one of the leading Indian merchants. The Tagores` were a cultured and wealthy family, and Rabindranath`s father, Debendranath, was one of the leaders of the Brahmo Samaj. Rabindranath Tagore was born in an atmosphere of the advent of new Bengali ideals. Rabindranath`s progressive views and ideals can be attributed to his family`s belief in synthesis of old and new influences. The poet`s early life was spent in an atmosphere of religion and arts, principally literature, music and painting. Tagore`s philosophies and way of living was heavily influenced by the concepts of Vedas and Upanishads. In music Tagore`s training was classical Indian, though as a composer, he rebelled against the tyranny of classical orthodoxy, and introduced many variations of form and phrase, notably from Bengali folk music of the Baul and Bhatiyali type.

Rabindranath wrote his first poem at the age of six and as a young boy studied the classical poetry of Kalidasa. He also studied the Upanishads, languages and modern sciences. He did his basic education at home. His home schooling, life in Shilaidaha, and travels made Tagore a nonconformist and pragmatist. However seeking to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, England in 1878; later, he studied at University College London, but returned to Bengal in 1880 without a degree.

Rabindranath wrote his first poem at the age of six and as a young boy studied the classical poetry of Kalidasa. He also studied the Upanishads, languages and modern sciences. He did his basic education at home. His home schooling, life in Shilaidaha, and travels made Tagore a nonconformist and pragmatist. However seeking to become a barrister, Tagore enrolled at a public school in Brighton, England in 1878; later, he studied at University College London, but returned to Bengal in 1880 without a degree.

Achievements of Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore`s literary reputation is disproportionately influenced by regard for his poetry; however, he also wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas and thousands of songs. Of Tagore`s prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; indeed, he is credited with originating the Bangla-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic and lyrical nature. However, such stories mostly were borrowed from deceptively simple subject matter - the lives of ordinary people.

Rabindranath Tagore`s literary reputation is disproportionately influenced by regard for his poetry; however, he also wrote novels, essays, short stories, travelogues, dramas and thousands of songs. Of Tagore`s prose, his short stories are perhaps most highly regarded; indeed, he is credited with originating the Bangla-language version of the genre. His works are frequently noted for their rhythmic, optimistic and lyrical nature. However, such stories mostly were borrowed from deceptively simple subject matter - the lives of ordinary people.

Literary Works of Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas, including "Chaturanga", "Shesher Kobita", "Char Odhay", and "Noukadubi". "Ghare Baire" (The Home and the World) through the lens of the idealistic zamindar protagonist Nikhil excoriates the rise of Indian nationalism, terrorism and religious zeal in the Swadeshi movement. In some sense, "Gora" shares the same theme, raising controversial questions regarding the Indian identity.

Another powerful story is "Yogayog" (Nexus), where the heroine Kumudini is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil. In it, Tagore demonstrates his feminist leanings, using pathos to depict the plight and ultimate demise of Bengali women trapped by pregnancy, duty and family honour. He also treats the decline of Bengal`s landed oligarchy.

Other novels were more uplifting. "Shesher Kobita" is his most lyrical novel, with poems and rhythmic passages written by the main character (a poet). It also contains the elements of satire and postmodernism attacking an oppressively renowned poet who, incidentally, goes by the name of Rabindranath Tagore. Though his novels remain among the least-appreciated of his works, they have been given renewed attention via film adaptations by many directors like Satyajit Ray. These include "Chokher Bali" and "Ghare Baire"; many have soundtracks featuring selections from Tagore`s own Rabindrasangeet.

Tagore also wrote many non-fiction books, writing on topics ranging from Indian history to linguistics. In addition to autobiographical works, his travelogues, essays, and lectures were compiled into several volumes, including "Iurop Jatrir Patro" (Letters from Europe) and "Manusher Dhormo" (The Religion of Man).

Other Literary Achievements of Rabindranath Tagore

Some of his literary achievements are as follows:

•In 1890, while on a visit to his ancestral estate in Shelaidaha, his collection of poems, "Manasi", was released. The period between 1891 and 1895 he authored a massive three volume collection of short stories, "Galpaguchchha".

•In 1901, he moved to Shantiniketan, where he composed "Naivedya", published in 1901 and "Kheya", published in 1906. By then, several of his works were published and he had gained immense popularity among Bengali readers.

•In 1912, he went to England and took a sheaf of his translated works with him. There he introduced his works to some of the prominent writers of that era, including William Butler Yeats, Ezra Pound, Robert Bridges, Ernest Rhys, and Thomas Sturge Moore.

•From May 1916 to April 1917, he stayed in Japan and the U.S. where he delivered lectures on "Nationalism" and on Personality".

•In 1920s and 1930s, he travelled extensively around the world; visiting Latin America, Europe and South-east Asia. During his extensive tours, he earned a cult following and endless admirers.

Achievements Given to Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore was given the following recognitions for his literary works:

•For his momentous and revolutionary literary works, Tagore was honored with the Nobel Prize in Literature on 14 November 1913.

•He was also conferred knighthood in 1915, which he renounced in 1919 after the Jallianwallah Bagh carnage.

•In 1940, Oxford University awarded him with a Doctorate of Literature in a special ceremony arranged at Shantiniketan.

Rabindranath as a Poet

Rabindranath Tagore was known for his different forms of creative writing such as essays, letters, short stories, novels and dramas and is best known for his poems. His poems reflected his beliefs and his feelings, be it of protest against wrong done or of support for a humanitarian cause. His first book, a collection of poems, appeared when he was 17; Tagore`s friend who wanted to surprise him published it. In East Bengal (now Bangladesh) he collected local legends and folklore and wrote seven volumes of poetry between 1893 and 1900, including Sonar Tari (The Golden Boat), 1894 and Khanika, 1900. More important was that Tagore wrote in the common language of the people and abandoned the ancient for of the Indian language. This was something that was hard to accept among his critics and scholars.

Rabindranath Tagore was known for his different forms of creative writing such as essays, letters, short stories, novels and dramas and is best known for his poems. His poems reflected his beliefs and his feelings, be it of protest against wrong done or of support for a humanitarian cause. His first book, a collection of poems, appeared when he was 17; Tagore`s friend who wanted to surprise him published it. In East Bengal (now Bangladesh) he collected local legends and folklore and wrote seven volumes of poetry between 1893 and 1900, including Sonar Tari (The Golden Boat), 1894 and Khanika, 1900. More important was that Tagore wrote in the common language of the people and abandoned the ancient for of the Indian language. This was something that was hard to accept among his critics and scholars.

Though Rabindranath was sent by his father to manage the tenants of his family estate, it proved to be Rabindranath`s most creative and productive literary periods. Those ten years that he spent in the estates brought him into contact with nature and the common man`s life. He acknowledged the influence of that contact on his mind as `beyond measure`. Living mostly in his `Padma Boat` and watching life through its windows as he sailed up and down the rivers in it, a whole new world of sights and sounds and feelings opened up before him. The external world of nature fascinated him and became a source of deeper reflection in his works.

The years that followed his stay in East Bengal were of great sorrow in his life starting with the death of his wife in the year 1902. A few months after his wife`s death their second daughter Renuka fell ill. His renowned collection of poems for children called sisu (child) was written at this time while nursing Renuka and looking after the two daughters in absence of their mother. The poems are full of innocent delight that nobody could tell how anxious and grief-stricken he must have been at the time.

It is worth noting that the sisu poems are of the same year as the collection called smaran (in memoriam) all written after his wife`s death. In 1903, nine months after the death of his wife Renuka died. In a poem written at that time he identified himself with a beggar woman who was stopped by a prince asking for alms. Embarrassed, she took out a copper coin from her bag and put it in his hand. When she returned home she found a gold coin in her bag and broke down thinking "why did I not give him my all"?

It is worth noting that the sisu poems are of the same year as the collection called smaran (in memoriam) all written after his wife`s death. In 1903, nine months after the death of his wife Renuka died. In a poem written at that time he identified himself with a beggar woman who was stopped by a prince asking for alms. Embarrassed, she took out a copper coin from her bag and put it in his hand. When she returned home she found a gold coin in her bag and broke down thinking "why did I not give him my all"?

The year 1906-16 constituted a most profound phase of Rabindranath`s creative life. Much of Tagore`s ideology came from the teaching of the Upahishads and from his own beliefs that God can be found through personal purity and service to others. He stressed the need for new world order based on transnational values and ideas of "unity consciousness." Each of his work seemed like an offering to God or finding in God `the medium of higher love shorn of all superficial ornaments`. Coming from an inner surrender, after much personal pain, the language of the poems was simple and direct. Whether written to find inner peace when facing the deaths of his beloved one`s or written for the future of his country, or written as poems of romantic love, those poems of the Gitanjali genre were like prayers to his lord.

Many of his poems are actually songs, and inseparable from their music. Tagore`s `Our Golden Bengal` became the national anthem of Bangladesh. Only hours before he died on August 7, in 1941, Tagore dictated his last poem. Infact his critics say that he wrote some of his finest poetry and drama in the final decade of his life from 1930 to 1940. They term this period as the `Last Harvest`. During this period he wrote seven volumes of verse of which four were prose poems. These writings reflected the issue of `untouchability` and `depressed humanity` that was prevalent at that time.

Among his fifty and odd volumes of poetry are Manasi (1890) [The Ideal One], Sonar Tari (1894) [The Golden Boat], Gitanjali (1910) [Song Offerings], Gitimalya (1914) [Wreath of Songs], and Balaka (1916) [The Flight of Cranes]. The English renderings of his poetry, which include The Gardener (1913), Fruit-Gathering (1916), and The Fugitive (1921), do not generally correspond to particular volumes in the original Bengali; and in spite of its title, Gitanjali: Song Offerings (1912), the most acclaimed of them, contains poems from other works besides its namesake. Tagore`s major plays are Raja (1910) [The King of the Dark Chamber], Dakghar (1912) [The Post Office], Achalayatan (1912) [The Immovable], Muktadhara (1922) [The Waterfall], and Raktakaravi (1926) [Red Oleanders].

Tagore remained a well-known and popular author in the West until the end of the 1920s, but nowadays he is not so much read.

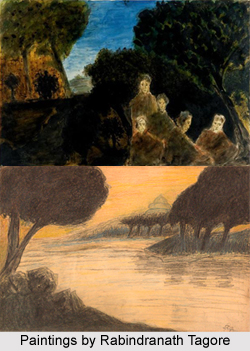

Rabindranath Tagore as a Painter

Rabindranath Tagore as a painter made a major contribution to the evolution of Indian art by opening the `Kala Bhavan` which proved to be a decisive land mark in the history. He was born in Jorasanko on 7th May 1861. His early life was spent in an atmosphere of religion and arts, principally literature, music and painting. He learnt drawing in his childhood and was attracted to the sketches drawn by his elder brother Jyotirindranath Tagore. In 1917 he founded the innovative Viswa Bharati University in the rural settings of Shantiniketan. He quietly opened the art wing of his university called `Kala Bhavan` after the Jallianwalabagh Bagh massacre.

Rabindranath Tagore as a painter made a major contribution to the evolution of Indian art by opening the `Kala Bhavan` which proved to be a decisive land mark in the history. He was born in Jorasanko on 7th May 1861. His early life was spent in an atmosphere of religion and arts, principally literature, music and painting. He learnt drawing in his childhood and was attracted to the sketches drawn by his elder brother Jyotirindranath Tagore. In 1917 he founded the innovative Viswa Bharati University in the rural settings of Shantiniketan. He quietly opened the art wing of his university called `Kala Bhavan` after the Jallianwalabagh Bagh massacre.

He had invited like-minded painters like Nandalal Bose to run Kala Bhavan with a free hand thereby encouraging the evolution of an original vision, reflecting the intuition and expression of the students. His famous world appearance as painter in France in the year 1930 was not unexpected. In 1926 Tagore had long discussions on his art with Romain Rolland. Romain Rolland who was himself a Nobel laureate wrote in his book `Inde-journal`, on 3rd July, 1926 " other day Tagore was discussing on his application of colour in paintings. He likes very little red colour, the dominance of red colour in Italian village did not attract him. His love goes violet and blue and he has more liking for green." Tagore had discussions about art with another Nobel Laureate, French poet Saint John Perse also.

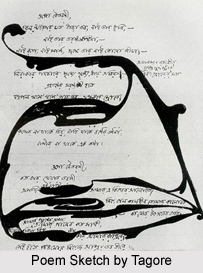

Rabindranath had never any formal training in art. He transformed his lack of formal training of art into an advantage and opened new horizons as far as the use of line and colours are concerned. He was prolific in his paintings and sketches and produced over 2500 of these within a decade.

Over 1500 of them are conserved in Viswa-Bharati, Shantiniketan. It is evident that in his search of newer form of expression in line and colour he tried to express something different from what he did in his poetry and songs. He seemed to explore darkness and mystery in his drawings.

Rabindranath had never any formal training in art. He transformed his lack of formal training of art into an advantage and opened new horizons as far as the use of line and colours are concerned. He was prolific in his paintings and sketches and produced over 2500 of these within a decade.

Over 1500 of them are conserved in Viswa-Bharati, Shantiniketan. It is evident that in his search of newer form of expression in line and colour he tried to express something different from what he did in his poetry and songs. He seemed to explore darkness and mystery in his drawings.

His self portraits are true representation of style. According to the scholars his self-portraits reflect a deeper psychological need - that of a creative person always in search of self. His self portrait stands as an art of sheer excellence. He was immensely attracted to primitive art. Distortion of form and the aberrant use of colour characterized his paintings. Theories of colour, mysticism and contemporary speculations are likely to have interested him and this has found expressions in his paintings. Silence is the chief theme in his paintings. Colour, season and emotion all gain a remarkable dimension in Tagore`s paintings. His paintings had a strange surrealism and bizarre emotions.

In spring 1930, when on a tour to France, Tagore was advised, by some art critics of local newspapers who saw his paintings, to hold an exhibition in Paris. He held the first public and international exhibition of his paintings in Paris in May 1930, at the Gallerie Pigalle. The exhibition was later held in different countries in Europe in the same year. India and his home town Calcutta hosted an exhibition only in 1931, a year later of Paris exhibition. Tagore`s paintings and sketches fascinated young German students. In Tagore`s own words, "The world speaks to me in colours, my soul answers in music". Tagore died on August 7, 1941. Tagore`s contribution to the art of India remains one of the most important.

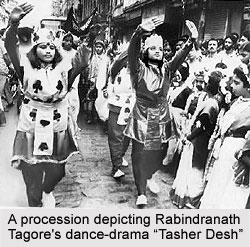

Rabindranath Tagore as a Dramatist

Rabindranath Tagore is considered as "sui generic" in Bengali theatre and dramatic Bengali literature. It is not possible to assign him a particular place chronologically. Nor is it easy to label his plays with useful tags, or define their relationship with the theatre. He wrote a large number of plays over a long period of time. Their variety in purpose, theme, structure, language and treatment is astonishing. Indeed, a number of them fall, at least by definition, beyond legitimate drama. His plays and his ideas of theatre developed along lines differing from the general direction of development of Bengali drama and theatre. They had little influence on other playwrights and his attitude to the theatre in Kolkata was cool, distant or, at best, ambivalent. He allowed many of his plays to be staged in the professional theatres but generally disapproved of their ways. Lastly, his own ideas changed over the years.

Rabindranath Tagore is considered as "sui generic" in Bengali theatre and dramatic Bengali literature. It is not possible to assign him a particular place chronologically. Nor is it easy to label his plays with useful tags, or define their relationship with the theatre. He wrote a large number of plays over a long period of time. Their variety in purpose, theme, structure, language and treatment is astonishing. Indeed, a number of them fall, at least by definition, beyond legitimate drama. His plays and his ideas of theatre developed along lines differing from the general direction of development of Bengali drama and theatre. They had little influence on other playwrights and his attitude to the theatre in Kolkata was cool, distant or, at best, ambivalent. He allowed many of his plays to be staged in the professional theatres but generally disapproved of their ways. Lastly, his own ideas changed over the years.

Like many other playwrights/dramatists he had an early fascination for the theatre and had acted before he wrote his first play at the age of twenty. The ancestral home of the Tagores at Jorasanko in north Kolkata had already been humming with artistic and literary activities when Rabindranath was born in 1861.

Rabindranath`s first stage appearance was in 1877 in a family production of a play by his elder brother, Jyotirindranath Tagore. His first `public` appearance as an actor was in his own Valmiki Pratibha, an episodic musical on the legendary author of the Ramayana.

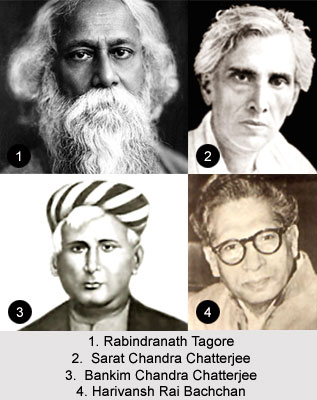

It was staged before an invited audience which included many eminent persons like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Haraprasad Sastri and Sir Gurudas Banerjee. From then on, when he was twenty-one, Tagore directed, produced and acted in many of the forty odd plays, long and short, that he wrote. He was seventy-five when he last appeared in Sarodatsab, staged in 1935 at Santiniketan, where he mostly stayed during the latter half of his life and where he staged many of his plays. For nearly five decades therefore he was interested in the theatre as dramatist, actor, composer and director.

It was staged before an invited audience which included many eminent persons like Bankim Chandra Chatterjee, Haraprasad Sastri and Sir Gurudas Banerjee. From then on, when he was twenty-one, Tagore directed, produced and acted in many of the forty odd plays, long and short, that he wrote. He was seventy-five when he last appeared in Sarodatsab, staged in 1935 at Santiniketan, where he mostly stayed during the latter half of his life and where he staged many of his plays. For nearly five decades therefore he was interested in the theatre as dramatist, actor, composer and director.

His first play Valmiki Pratibha was written in 1881. The story is expressed through a string of songs. A certain amount of dramatic conflict is there but it gets submerged in the music and the songs. Much later, when he had settled down at Santiniketan, he wrote a cycle of plays like Rituranga, Basanta, Phalguni and Sesh Barshan celebrating the seasons with an assemblage of songs loosely held together by the thinnest of dramatic threads. Some of his major dance dramas are - Chandalika, Tasher Desh, Chitrangada and Shyama- were written in the thirties when Tagore was past seventy. The dramatic element in them is considerable but the form which he evolved to expound the dramatic themes is a compound of dances, mime, music and choreography. They have their unique appeal but, like the musical and operatic plays, they have been the preserve of singing and dancing troupes and have had little influence on Bengali theatre.

Tagore`s reputation as a playwright had a mixed fare among the people. There were some that brought him near the professional theatre, while others pushed him away. The first full-fledged drama he wrote was Raja O Rani (1889) - five-act verse-play, it is full of melodramatic happenings, external conflict and romantic passion. It was popular in the commercial theatre of Kolkata.

Raja O Rani was followed by Visarjan, another full-length verse-play. For two decades after Visarjan, there was no major plays written by Tagore- and this was the period when his poetry was undergoing a transformation in content and form. However, his play, Raja, appeared in 1910, was a different sort of play from the ones he had written before. Some indication of this is available in the two plays Sarodotsab and Prayaschitta he wrote before Raja. In both "externality" and "action" give way to philosophical "internality" and contemplative "inaction". It is mainly with Raja that kick-started the golden period of a cycle of plays. Raja helped to do away with many conventions of dramatic writing such as a rounded plot, narrative content, type characters etc.

Raja O Rani was followed by Visarjan, another full-length verse-play. For two decades after Visarjan, there was no major plays written by Tagore- and this was the period when his poetry was undergoing a transformation in content and form. However, his play, Raja, appeared in 1910, was a different sort of play from the ones he had written before. Some indication of this is available in the two plays Sarodotsab and Prayaschitta he wrote before Raja. In both "externality" and "action" give way to philosophical "internality" and contemplative "inaction". It is mainly with Raja that kick-started the golden period of a cycle of plays. Raja helped to do away with many conventions of dramatic writing such as a rounded plot, narrative content, type characters etc.

The two plays Tagore wrote after Raja were Achalayatan and Dakghar, both written in 1912. The first carried a lighter philosophical burden than Raja and is more dramatic in its portrayal of conflict. The second play, Dakghar, is the most widely known of Tagore`s plays, outside Bengal at any rate. It was written at the time when Tagore was writing Gitanjali and Gitali which won him the Nobel Prize for literature in 1913. Simple to the point of starkness in its structure and diction, Dakghar has the power and poignancy of symbolist drama at its best.

The cycle of symbolist plays reached its culmination in Raktakarabi in 1924. More complex in design than the other plays, it has a richness of imagery and texture unattained before. A few years earlier he had written another play in a similar vein- Muktadhara. Both Muktadhara and Raktakarabi are a condemnation of a civilisation dominated by these evils.

Tagore himself, with his enormous talent as an actor and his long experience of producing plays, was chary of staging them. To the theatregoer, therefore, Tagore came to be known as a dramatist not through the major plays he wrote but through an overblown melodrama, Raja O Rani, and two comedies Chirakumar Sabha and Sesh Raksha. The last two were quite popular and staged in different theatres in the late twenties and early thirties. They are slight comedies of error shakily standing on the feeble foundation of mistaken identity.

Tagore wrote plays intermittently over fifty years. As noted before, many of them can hardly be called by that name. He was also in the habit of revising and re-writing his plays and turning his novels and stories into plays.

Tagore`s ideas on the theatre crystallised after a gradual process of re-thinking. It is ironical that they were rejected by the Bengali theatre when they, so to speak, became more Bengali. After writing plays on western models Tagore changed to forms that were closer to Bengali folk forms. His plays were, of course, vastly superior to the work of the jatra play wrights but the formal imagination was consanguineous. Bengali theatre in its conscious striving to emulate English theatre had denied itself that imagination while adopting, unconsciously or otherwise, many of its debased features. A further irony was that the two principal architects of Bengali theatre, Girish Chandra Ghosh and Sisir Kumar Bhaduri, realised the dilemma and talked of the necessity of drawing upon the vital sap of folk forms.

By the time Dakghar was produced in 1917 at Vichitra Hall, an annexe of the Jorasanko House, before an audience which included, among others, Mahatma Gandhi, Bal Gangadhar Tilak, Pandit Malaviya and Mrs. Annie Besant, the change was noticeable, although Tagore had not done away with sets altogether.

Tagore`s views, quoted at some length, would seem to suggest that he had foreseen some of the dead ends and the dilemma of a bastardised theatre. In his own way he created his dramatic and theatrical oeuvres, and tried to indicate the way in which a genuine

Indian theatre could come into being; a theatre which belonged to the soil and was true to its native genius, which sustained itself on plays inspired by Indian ideas of synthesis rather than conflict, on internality rather than external actions and which drew upon traditional sources to express universal truths. But then the Bengali theatre was a product of a set of socio-economic and cultural circumstances arising from certain historical situations. Tagore pleaded for small, intimate theatres which, as he put it, ``should aim to provide a meeting place for only the discerning and the cultivated." But possibly he did not see that such theatres gain significance only when there pre-exists a theatre with a wide popular base. It is doubtful if, given the conditions, such a theatre could have come into existence except in the way it did. As it happened, the rejuvenation of Bengali theatre in the fifties was in fact brought about by the little theatres Tagore talked of. The views of many who formed them were in some respects similar to Tagore`s. But any firm or generalised inference about Tagore`s direct influence on the New Drama movement will not bear scrutiny. At the most it can be said that some of the thrust of Bengali minority theatre`s new directions in the post-war and post-independence periods was derived from Tagore`s ideas and exhortations

Indian theatre could come into being; a theatre which belonged to the soil and was true to its native genius, which sustained itself on plays inspired by Indian ideas of synthesis rather than conflict, on internality rather than external actions and which drew upon traditional sources to express universal truths. But then the Bengali theatre was a product of a set of socio-economic and cultural circumstances arising from certain historical situations. Tagore pleaded for small, intimate theatres which, as he put it, ``should aim to provide a meeting place for only the discerning and the cultivated." But possibly he did not see that such theatres gain significance only when there pre-exists a theatre with a wide popular base. It is doubtful if, given the conditions, such a theatre could have come into existence except in the way it did. As it happened, the rejuvenation of Bengali theatre in the fifties was in fact brought about by the little theatres Tagore talked of. The views of many who formed them were in some respects similar to Tagore`s. But any firm or generalised inference about Tagore`s direct influence on the New Drama movement will not bear scrutiny. At the most it can be said that some of the thrust of Bengali minority theatre`s new directions in the post-war and post-independence periods was derived from Tagore`s ideas and exhortations

Rabindranath and Santiniketan

By 1863 Rabindranath turned his attention to the Santiniketan School after withdrawing from the Swadeshi movement. Later on, Rabindranath founded the Santiniketan School in his father`s ashram in 1901. Santiniketan was located within two miles of the Bolpur railway station on the East Indian Railway line. The school had the advantage of being situated in the heart of nature but not too far from the city. The girl`s school was added in the year 1908. But it did not survive for more than a year owing to a tragic suicide of a school student. But again in 1922, a separate wing for girls was formed.

By 1863 Rabindranath turned his attention to the Santiniketan School after withdrawing from the Swadeshi movement. Later on, Rabindranath founded the Santiniketan School in his father`s ashram in 1901. Santiniketan was located within two miles of the Bolpur railway station on the East Indian Railway line. The school had the advantage of being situated in the heart of nature but not too far from the city. The girl`s school was added in the year 1908. But it did not survive for more than a year owing to a tragic suicide of a school student. But again in 1922, a separate wing for girls was formed.

In his school he ensured that the students are taught the importance of Indian inheritance and at the same time give it a universal humanist outlook. The cadres and the teachers of his school came from all over the world. The students had hardly any syllabus. They were expected to grow through their own experiences including the bad one`s. The goal of learning was to synthesize knowledge and feeling. Also, learning by doing was given uttermost importance. The education was intended for both city as well as the village children. The sole aim of bringing them together was to encourage social mingling, exchange of ideas, knowledge and experiences. He hoped to give life to Upanishadic concept in his Santiniketan institution as he felt that it would lead to the regeneration the country.

The arrangements at Santiniketan were extremely primitive. The day for the students used to begin at 4.45 in the morning and would end by 9.00 in the night. However, soon Rabindranath realized that a Brahmacharya Ashram was not his idea of a new and modern education. Though he valued the primitive nature of Santiniketan, his ideal school had to do much more than that, especially with regard to opening up the student`s minds to a relationship with the world. This gave birth to Visva-Bharati (a central university of the government of India).

The idea of happiness the most fundamental emotions, was used innovatively in Santiniketan. There was a minimum of curriculum but a round-the-clock routine of varied activities. His idea was that children should be surrounded with the things of nature that have their own educational value. He attached great importance to self-expression. He expected his students to feel every happiness, big or small, by being given `a full life`. The other idea in the school was freedom. The students were encouraged to take decisions on matters concerning their life. He described Santiniketan School as an indigenous attempt in adapting modern methods of education in a truly Indian cultural environment.

The idea of happiness the most fundamental emotions, was used innovatively in Santiniketan. There was a minimum of curriculum but a round-the-clock routine of varied activities. His idea was that children should be surrounded with the things of nature that have their own educational value. He attached great importance to self-expression. He expected his students to feel every happiness, big or small, by being given `a full life`. The other idea in the school was freedom. The students were encouraged to take decisions on matters concerning their life. He described Santiniketan School as an indigenous attempt in adapting modern methods of education in a truly Indian cultural environment.

Reaching out to a larger humanity was essential and hence villages surrounded the Santiniketan ashram. Students were regularly sent to learn about the conditions of the villagers. Rabindranath was of the opinion that majority of India lived in the villages and were being kept out of mainstream of Indian life. Colonial education did not reach the farmer, the oil grinder and potter. Bearing in mind the need to evoke moral responsibility among the educated class, he would encourage his students to build relationship with the villagers. Rabindranath was determined to change the situation by creating a new education, which would apply economics, agriculture, healthcare and other everyday sciences to the villages.

Rabindranath would contribute a large sum of his income to Santiniketan. Santiniketan did not have any income of its own besides the annual maintenance grant of Rs.1800 from the Santiniketan Trust established by his father. To start the school, he had to sell almost everything he possessed including his wife`s jewellery, his gold watch and even his seaside bungalow at Puri. For some years at the outset, in keeping with the school`s ideals, the students were not charged tuition fees. But as the financial burden grew, meeting the daily ends became difficult.

He would often go on `fund-raising` missions in India and the West to raise funds for his institution. Those missions too proved unsuccessful. His lecture tour in America in 1916-1917 brought him recognition but failed to produce the expected financial returns. Over the years Rabindranath found a surer way of generating funds. He did it by touring the country with performances of his dance-dramas by Santiniketan students. From 1930, a regular income of around Rs.30, 000 came from that source and listed under `Proceeds of Performances` in their accounts books.

In spite of his fragile health Rabindranath continued to make tours. Santiniketan had become central to his life. Besides the difficulty in raising funds, Santiniketan had to face other problems too. People used to look down upon the institution and did not appreciate his innovative ideas in education. He had difficulty even in getting pupils when the school was first established; those who were brought were mostly difficult children. It took years before the school was recognized as anything but a reformatory.

In addition, the Britishers were suspicious of the school`s objectives and issued secret circulars warning their officials against sending their children there. Rabindranath could have abandoned this experiment but on the contrary but it was just the reverse. He continued to struggle with a sense of fulfillment. Santiniketan in his words was a `sapling`, which was to grow into Visva-Bharati, `a widely branching tree`.

In addition, the Britishers were suspicious of the school`s objectives and issued secret circulars warning their officials against sending their children there. Rabindranath could have abandoned this experiment but on the contrary but it was just the reverse. He continued to struggle with a sense of fulfillment. Santiniketan in his words was a `sapling`, which was to grow into Visva-Bharati, `a widely branching tree`.

The first foreign student to come to Santiniketan was Hori San from Japan. Step by step Santiniketan moved from being a collection of separate educational experiments into a well-knit whole- a school, a college, a department of higher studies and research, a center of music and art. Within two miles from Santiniketan was an institute of rural reconstruction called `Sriniketan`. He now coined the term `Visva-Bharati` for the whole institution, Santiniketan and Sriniketan. With Visva-Bharati`s inauguration in 1921 its doors were thrown open to men and women from elsewhere to collaborate in intellectual companionship and social action. Visva-Bharati is now a degree giving university. Santiniketan College that was founded by Tagore in 1918 got affiliated to Calcutta University in 1921.

Nobel Prize and Rabindranath Tagore

With the combined efforts of both Rothenstein and W.B. Yeats, who were tremendously impressed by Tagore`s Gitanjali, a private edition of the English Gitanjali was published through the Indian Society of London. Even before the Nobel Prize was announced, Gitanjali became widely accepted all over. Finally the news of the Nobel Prize reached him on 13th November 1913. In the summer of 1912, Rabindranath took to England some translations of his favourite poems. The Nobel Prize for Literature brought Tagore into the public eye in both the East and West. He later on often travelled to the U.S and Europe to share his poetry and raise funds for his own ashram.

After winning the award, there was a great demand for his work in English. In response to that demand he put together more and more translations of his writings. Tagore was also awarded the knighthood in 1915, but he surrendered it in 1919 as a protest against the Massacre of Amritsar, where British troops killed some 400 Indian demonstrators protesting colonial laws.

Later Years and Death of Rabindranath

In his later years, Tagore suffered from persistent pain and subsequent periods of sickness. He even suffered from coma during 1937. The poetry written by Tagore in these twilight years are unique for their obsession with death; these more profound and mystical experimentations allowed Tagore to be branded a modern poet. Rabindranath Tagore died on August 7th 1941 in his Jorasanko mansion, at the age of 80.

Even after his death, Rabindranath Tagore remained a towering figure in the millennium-old literature of Bengal. His poetry as well as his novels, short stories, and essays are very widely read, and the songs he composed reverberate around the eastern part of India and throughout Bangladesh.

Books by Rabindranath Tagore

The Books by Rabindranath Tagore essentially show social consciousness. Rabindranath Tagore was a Renaissance man. An early advocate of the Independence of India, Tagore, in his novels raised a silent protest against the socio-political repression and suppression. Combining the traditional Indian culture with Western ideas, Rabindranath Tagore was the first to bring an element of psychological realism to his novels. Truly a modern man, Rabindranath Tagore, advocated for the freedom of women. The common homespun women of the aristocratic family were the important characters he dealt with. Tagore in his novels verbalized the women empowerment and his women have the verve of energy, which makes them come out from the uncomplicated family life and participate in the radical politics. In the contemporary patriarchal society, Rabindranath Tagore, deviates from the normal trend and etches out the women as the sole power.

The Books by Rabindranath Tagore essentially show social consciousness. Rabindranath Tagore was a Renaissance man. An early advocate of the Independence of India, Tagore, in his novels raised a silent protest against the socio-political repression and suppression. Combining the traditional Indian culture with Western ideas, Rabindranath Tagore was the first to bring an element of psychological realism to his novels. Truly a modern man, Rabindranath Tagore, advocated for the freedom of women. The common homespun women of the aristocratic family were the important characters he dealt with. Tagore in his novels verbalized the women empowerment and his women have the verve of energy, which makes them come out from the uncomplicated family life and participate in the radical politics. In the contemporary patriarchal society, Rabindranath Tagore, deviates from the normal trend and etches out the women as the sole power.

Ideas of Rabindranath Tagore

Much of Tagore`s ideology, as is revealed in his writings comes from the teaching of the Upanishads and from his own beliefs that God can be found through personal purity and service to others. He stressed on the need for new world order based on translational values and ideas, the unity consciousness. Politically active in India, Tagore was a supporter of Mahatma Gandhi, but warned of the dangers of nationalistic thought. Unable to gain ideological support to his views, he retired into relative solitude. And during this solitude he travelled widely and produced a number of travel accounts, which are the treasures of the Indian Literature. A genius, Rabindranath Tagore is considered as one of the famous luminaries of Indian Literary World. Tagore"s books are one kind of assets. His works testimonies the Bengali culture tradition and social life of the contemporary.

Poetry by Rabindranath Tagore

Poetry by Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore`s poems are varied in style and subject matter. Tagore`s poetry became most innovative after his exposure to rural Bengal`s folk music including Baul ballads. During his Shilaidaha stay, his poetry took more to a lyrical quality. The "Africa", "Proshno", "Bhogno Hridoy", "Chhabi o Gan", "Camalia", etc., are examples of his important poems. Gitanjali is his most known collection, which won him the Nobel Prize for Literature. This collection replicates the true Indian Philosophy in all its glory. Gitanjali, an anthology of poem advocates the idea of serving the poor, and the destitute than to serve the God. Gitanjali is a part of the UNESCO Collection of Representative Works. Tagore is most popular for his poetry. Besides poetry he also wrote novels, stories, and non fictional books.

Novels of Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore wrote eight novels and four novellas. Among them `Gora` raises the question regarding Indian identity. This book is set amidst a political background. Gora is a social chronicle depicting the entire Bengali society in a harmonious way and at the same time raising a protest against the social taboos. "Rajarshi", "Chaturanga", "Shesher Kobita", "Char Odhay", "Noukadubi" and "The home and the World" (Ghare Baire) are also important novels of Tagore. Within the political background of pre independence, "Ghare baire" is a social drama depicting the extramarital relationship of the woman protagonist. In the novel "Jogajog", the woman is torn between her pity for the sinking fortunes of her progressive and compassionate elder brother and his foil: her exploitative, rakish and patriarchical husband. In "Chokher Bali", Tagore records 20th century Bengali society.

Plays by Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore wrote plays like "Chitra", "Dak Ghor", "Chitrangada", "Raja and Valmiki-Pratibha". "Chitra" is a famous one act play. His "The King of the dark Chamber" also known as "Raktakarobi" or "Red Oleanders" reverberates the very rhythm of unearthly and personal stimulation of the individual in their eternal quest for beauty.

Stories by Rabindranath Tagore

Stories by Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore composed some beautiful stories which are worthy to read. "The Hungry Stones" is one of great importance. The winding alleyways of the human minds are the key theme of the poignant story - The Hungry Stones. `Kabuliwala" is another which depicts the friendship of a fruit seller from Kabul and little Mini irrespective of their age difference. Tagore`s "Galpaguchchha" remains constant as the most popular fictional work in Bengali literature. Its influence on Bengali art and culture cannot be overruled even to this day. Film director Satyajit Ray based his film "Charulata" on Tagore"s "Nastanirh" ("The Broken Nest"). The story has an autobiographical element within it, modelled to some extent on the wonderful relationship shared between Tagore and his sister-in-law, Kadambari Devi. Other stories of Tagore include "Atithi", "Strir Patra", "Haimanti", "Musalmanir Golpo", etc.

Non-fictional books of Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore wrote many non fictional books on a variety of subjects like Indian History, Linguistics, spirituality etc. His travelogues, essays, lectures and letters are complied in several volumes. He wrote Sadhana which includes the ideal way of spiritual upliftment. Among Tagore`s other notable non-fiction books are "Europe Jatrir Patro" and "Manusher Dhormo".

Mashi Novel by Rabindranath Tagore

`Mashi` is a novel written by Rabindranath Tagore which deals with one phase or another of the transition through which India is passing, and that transition is inspiring anxiety in the minds of men like Tagore. He is vitally interested in the preservation of Indian culture from the ravages of the vandal forces of indiscriminate Westernization.

`Mashi` is a novel written by Rabindranath Tagore which deals with one phase or another of the transition through which India is passing, and that transition is inspiring anxiety in the minds of men like Tagore. He is vitally interested in the preservation of Indian culture from the ravages of the vandal forces of indiscriminate Westernization.

Anyone who is an ardent fan of Rabindranath Tagore will be familiar with his deep insights into the human mind. Rabindranath Tagore always concentrates on different aspects of relationship. Sometimes he takes the political aspect while sometimes he is more into human relationship. Love has got different name in his different writings. Sometimes love is between brother-sister, lover-lovee, while sometimes it goes far beyond and reach the height.

Tagore was a man of principle. He never joined politics in an active manner. Though he was a very good friend of Mahatma Gandhi as well as Jawaharlal Nehtu. As well as literature Tagore had a great love of music, in particular Bengali music. He composed more than two thousand songs, both the music and lyrics. Two of them became the national anthems of India and Bangladesh. Tagore was not just a poet but also productive in the fields of art, music and education. Tagore played a large role in the artistic and cultural renaissance of India, which occurred in the 20th Century. Tagore was in very much love with his dream project Santiniketan. Tagore tried to fuse the best of Western and Eastern values. Fusing the spirituality of the East with the scientific progress of the West. He was very modern in his writing. He has written many contemporary write-ups that are still popular in the reader`s mind.

Synopsis:

`Mashi` is a creation of Rabindranath Tagore and the author wrote it in the year of 1918. This book of the author has come up with some new ideas and thoughts, which are suitable at the age of teens. At that time the human mind can take these type of literature very well. This book can change the perception of some persons about some specific subjects. It can make someone more aware of the incessant commentary that perpetually goes on in people`s minds. The characters are memorable. It can be felt they are laughing, talking and smiling. You can almost hear them speak. They speak differences and the conflict between them is what the story revolves around. The author expertly weaves together the conflicting emotions of three very different people. The tension in one person is contrasting with the calm persona of the other. Whereas the other character struggles to balance her joys and sorrows. In all, it is an intense study of the human mind in various stressful circumstances. It shows how different people interpret the same emotions in different ways and has their own ways of dealing with their adversities based on their previous experiences. It is experimented that if there are twelve persons in a room and someone tells something. The twelve persons can interpret it in twelve different ways.

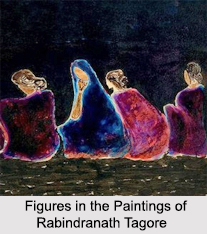

Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore

Rabindranath Tagore started painting and drawing at the age of 60 years. Many of his works have been exhibited in several national and international exhibitions. Tagore was likely red-green colour blind, which resulted in his works; the paintings showed strange colour schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was highly influenced by the works of the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein. National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi houses 102 works of Tagore in its collections.

Rabindranath Tagore started painting and drawing at the age of 60 years. Many of his works have been exhibited in several national and international exhibitions. Tagore was likely red-green colour blind, which resulted in his works; the paintings showed strange colour schemes and off-beat aesthetics. Tagore was highly influenced by the works of the Malanggan people of northern New Ireland, Papua New Guinea, Haida carvings from the Pacific Northwest region of North America, and woodcuts by the German Max Pechstein. National Gallery of Modern Art in Delhi houses 102 works of Tagore in its collections.

Animals Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore

Tagore"s initiated his arts with the doodles that turned crossed-out words and lines into images that assumed expressive and sometimes grotesque forms. The shapes and forms of the subjects were brought accidentally but often they seem to carry memories of primitive art subjects. Most of the paintings of this time represent animals. He inter-mingled the familiar with the unknown; the subjects of his paintings are movement of a living animal on to an imagined body, or a human gesture onto an animal body and vice versa.

Landscape Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore

Landscape Paintings of Rabindranath Tagore

Paintings made Tagore more observant and sensitive to the visible world . Landscape paintings of Rabindranath Tagore gave the visible world a definite expression, which in turn linked up with one of his older passions. During his childhood, Tagore spent a lot of time observing the nature through the windows. The world outside gave him a feeling of companionship and freedom. So, in these landscape paintings, done at his old age, he often portrayed the nature as bathing in the evening light.

Dramatic Scenes in Tagore"s Paintings

Rabindranath Tagore left his paintings free from any literary imagination by not giving them any names. The figures in his paintings reveal his experience of the theatre as a playwright, director and actor. The gestures of the figures do not represent everyday activities yet they all have a dramatic presence. The costumes of the figures and the furniture and objects surrounding them play a vital role in showing the paintings as a dramatic motif rather than ordinary one. The figures are not shown busy in narration but they invoke narrative potentiality, especially when they are juxtaposed with one another or shown in groups. The movements and the gestures of the figures are more sombre than usual and they do not mimic life. They make us think about emphatic immersion rather than mere recognition.

Faces and Characters in Tagore"s Paintings

Human face is the most common motif in Tagore"s paintings. This motif shows his infinite interest in human persona. In his stories, especially short stories, he linked human appearance with an inner human essence. He did so in paintings as well. Initially he turned the faces into a mask or a hieratic symbol of a social type in his paintings. His faces are varied in appearance and social stature and they encompass within their own lineaments of vast human experience.