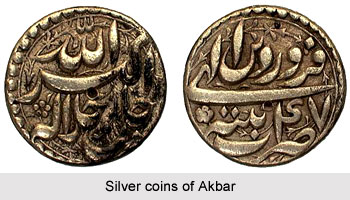

Coins of early medieval India suggest that there was a fairly logical reconstruction of the monetary systems. During the five centuries from AD 750 to AD 1250, a few superficially uniform coin types comprised monetary systems startling in their complexity and diversity. While some money forms remained within their locality of issue, others passed far and wide. The physical evidence is incontrovertible, that money and exchange were alive and vibrant throughout much of the area. Further, it has also been established by historians that there was some apparent shortages of the precious metals necessary for coinage in early medieval India. Far from being an era of static decline, monetary history reveals a time of sagacious and practical adjustments which maintained vigorous metal-based monetary systems.

Coins of early medieval India suggest that there was a fairly logical reconstruction of the monetary systems. During the five centuries from AD 750 to AD 1250, a few superficially uniform coin types comprised monetary systems startling in their complexity and diversity. While some money forms remained within their locality of issue, others passed far and wide. The physical evidence is incontrovertible, that money and exchange were alive and vibrant throughout much of the area. Further, it has also been established by historians that there was some apparent shortages of the precious metals necessary for coinage in early medieval India. Far from being an era of static decline, monetary history reveals a time of sagacious and practical adjustments which maintained vigorous metal-based monetary systems.

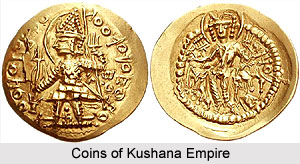

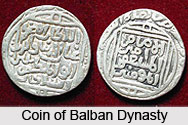

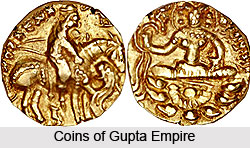

Further, it is quite suspected that in comparison to the earlier Gupta period and later Sultanate period, there was a paucity or scarcity of coinage throughout North India in the early medieval era. This is interpreted as indicating a general low level of exchange transactions, and hence a quiescence of trade and commerce. Gold coins were rarely issued after the fall of the Gupta Empire and even the silver and copper coinages are scarce and poor. Interpretation of the early medieval propensity for alloy coins is based on the actual pattern of coinage use. Until the end of the Gupta period, rulers took an active interest in the forms of their coinage, causing a great variety of coin types to be issued, all differentiable as to issuing state, king, legend, artistic design and sometimes even year of issue. This is reflected in numismatic literature, and museum catalogues, by the amount of attention devoted to these coins. When, as in the period AD 500 to AD 1000, coins ceased to be used as a message-bearing medium, a conservative retention of old coin-styles became the rule in North India. Specific series, notably the Indo-Sassanian and bull-and-horseman types, were issued by a number of dynasties with virtually no distinguishing marks to indicate the place of issue, issuing authority or date of manufacture. Only a barely perceptible evolution of style over the centuries is notable.

Historians clarify that there is a definite paucity of coin types in this period, but this is not evidence of a scarcity of circulating medium. So far, in the literature, there has been no assessment, rigorous or otherwise, of the numbers of coins originally produced and circulated. When reference is made to coin hoards of the early medieval period, rather than museum holdings, quite different conclusions are drawn about the abundance of coinage in the early medieval period. The northern portion of the subcontinent in the period AD 800 to AD 1200 contained a number of distinct currency zones or spheres. Within each zone, a single coinage form prevailed, and there was little overlap in areas of circulation of the major currencies. Two distinct distribution patterns of coins existed - some currency spheres were congruent with political boundaries, while other currency spheres seemed to have been unconstrained by political frontiers. It is remarked that only the coin forms of the latter show consistency of intrinsic value over time. While the regulation of manufacture and resultant control over the physical nature of the circulating medium remained a powerful privilege of government, the acceptableness of the circulating medium was subject to the influences and preferences of trading communities.

The early medieval period is considered to be an era of base metal alloy coinages, when the precious metals were not used in pure form in money. The value of a coin historically was related to its precious metal content, and determination of the proportion of precious metal in a coin is a necessary precondition to assessing its denomination. There-was some regional variation in this effect: the relative precious metal content of coins was not uniform from country to country. In the Ganga basin, the high price of silver was evident as early as the eighth century, but that of gold not until the eleventh century. It was only later, in the thirteenth century that pure gold and silver coins were restored at Delhi. The material requirements of the prolific coin production outstripped available sources of precious metals. The naturally-occurring gold and silver resources of North India were insufficient to support such a scale of coinage issues; only copper was available in significant quantities. Thus, the result was increased dependency on collected stock and foreign supplies of these precious metals for coinage purposes.