Fables in the Mahabharata occur in the form of the Itihasa-Samvadas. These are discourses clothed in the form of narratives (Samvada). They are not so much part of the Brahmanical epic poetry as they are of a kind of Ascetic poetry. It is closely related to the popular literature of fables and fairy-tales, partly because it draws upon the latter, and partly because it approaches it as closely as possible. While the Brahmanical legends, like the Brahmanical Itihasa-Samvadas, serve the special interests of the priests and teach a priestly morality, reaching its climax in the sacrificial service and in the worship of the Brahmins (more than of the gods), the Ascetic poetry rises to a general morality of mankind, which teaches, above all, love towards all beings and renunciation of the world.

Fables in the Mahabharata occur in the form of the Itihasa-Samvadas. These are discourses clothed in the form of narratives (Samvada). They are not so much part of the Brahmanical epic poetry as they are of a kind of Ascetic poetry. It is closely related to the popular literature of fables and fairy-tales, partly because it draws upon the latter, and partly because it approaches it as closely as possible. While the Brahmanical legends, like the Brahmanical Itihasa-Samvadas, serve the special interests of the priests and teach a priestly morality, reaching its climax in the sacrificial service and in the worship of the Brahmins (more than of the gods), the Ascetic poetry rises to a general morality of mankind, which teaches, above all, love towards all beings and renunciation of the world.

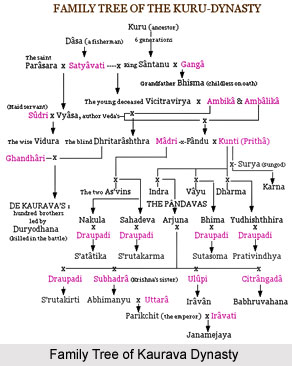

The oldest Indian fables are to be found in the actual epic and they serve for the inculcation of rules of Niti, i.e. worldly wisdom, as well as of Dharma or morality. Thus, a minister advises Dhritarastra to deal with the Pandavas in a similar manner as a certain jackal, who utilised his four friends, a tiger, a mouse, a wolf and an ichneumon, for the purpose of obtaining his prey but then cunningly got rid of them so that the prey remained for him alone. In another place Sisupala compares Bhishma with that old hypocritical flamingo, which always talked only of morality and enjoyed the confidence of all its fellow-birds, so that they all entrusted it with the keeping of their eggs, until they discover too late, that the flamingo eats the eggs. Delightful also is the fable of the treacherous cat, which Uluka, in the name of Duryodhana relates to Yudhisthir, at whom it is aimed. With uplifted arms the cat performs severe austerities on the bank of the Ganga River and he is ostensibly so pious and good that not only the birds worship him but even the mice entrust themselves to his protection. He declares himself willing to protect them but says that in consequence of his asceticism he is so weak that he cannot move. Therefore, the mice must carry him to the river where he devours them and grows fat. The wise Vidura, into whose mouth many wise sayings are placed, also knows many fables. Thus, he advises Dhritarastra not to pursue the Pandavas out of self-interest, that it may not befall him as it befell the king who out of greed killed the birds which disgorged gold, so that he then had neither birds nor gold. In order to bring about peace, he also relates the fable of the birds which flew up with the net which had been thrown out by the fowler but finally fell into the hands of the fowler because they began to quarrel with one another.

Most of the fables, as well as all the parables and moral narratives, are to be found in the didactic sections and in Books XII and XIII. Many of these recur in the Buddhistic and later collections of fables and fairy-tales, and some have been transmitted into European narrative literature.

The main point of all these narratives lies in the speeches of the characters. Some of these dialogues rank equally with the best similar productions of the Upanishad literature and of the Buddhist literature. For instance, the saying of King Jamba of Videha, after he has obtained peace of mind sounds as though it had been taken from an Upanishad: "O, immeasurable is my wealth, for I possess nothing. Though the whole of Mithila burn, nothing of mine burns."

The ancient Indian sects of ascetics hardly differed more distinctly from one another than, for instance, the various Protestant sects in Great Britain today. It is, therefore, no wonder that in the edifying stories, dialogues and maxims of the ascetic poetry which has been embodied in the Mahabharata, there are to be found so many thoughts which are in accord with the Upanishads as well as with the sacred texts of the Buddhists and the Jains.