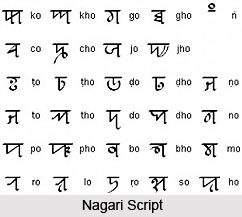

From the late 19th century, Devanagari script has been considered as the only effective writing system for Sanskrit language. As a consequential result, Sanskrit grammar has been, since primeval times influenced by several other linguistic dialects. This unique blend from Devanagari has occurred possibly because of the European practice of printing Sanskrit texts in this (Devanagari) script.

From the late 19th century, Devanagari script has been considered as the only effective writing system for Sanskrit language. As a consequential result, Sanskrit grammar has been, since primeval times influenced by several other linguistic dialects. This unique blend from Devanagari has occurred possibly because of the European practice of printing Sanskrit texts in this (Devanagari) script.

Grammatical Tradition of Sanskrit Grammar

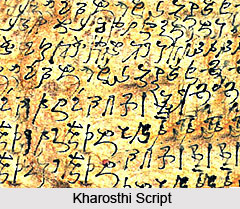

The earliest known inscriptions in Sanskrit date back to the 1st century B.C.E. They have been evidenced in the Brahmi script, originally utilised for Prakrit and not Sanskrit. Ironically, this phenomenon has been reported as a paradox due to very first evidence of written Sanskrit occurring centuries later than that of Prakrit languages, regarded as its linguistic successors. When Sanskrit was ultimately penned down, it was first employed for texts pertaining to administrative, literary or scientific domains; Sanskrit grammar had come into this category during its next phase. The hallowed and sanctified texts were preserved orally and consequently were set down in writing.

The grammatical traditions of Sanskrit grammar was first traced in late Vedic India and culminated in the Asthadhyayi of Panini, the first ever detailed and authentic treatise on Sanskrit grammar. The text consists of 3990 sutras circa 5th century B.C.E. After a century during which Panini existed, around 400 B.C.E., Katyayana had composed Vartikas, based upon Paninian sutras. Patanjali, who lived 3 centuries after Panini, scripted the Mahabhasya, known as the Great Commentary on the Asthadhyayi and Vartikas. Due to the sole basis of these 3 ancient Sanskrit grammarians, Sanskrit grammar is essentially named as Trimuni Vyakarana. To further comprehend the meaning of sutras, Jayaditya and Vamana penned the commentary named Kasika around 600 C.E. Paninian grammar is based upon 14 Shiva sutras, better referred to as aphorisms. Here, the entire Matrika (alphabet) is stated in truncated format. This abbreviation is further referred to as Pratyahara.

Verbs in Sanskrit Grammar

Sanskrit grammar possesses 10 classes of verbs which are classified into 2 broad groups comprising of: athematic and thematic. The thematic verbs are so named because an `a`, called the theme vowel, is introduced in between the stem and the ending. And those without it are called athematic verbs. This helps to make the thematic verbs in general more habitual. Exponents utilised in verb unification comprise prefixes, suffixes, infixes and reduplication. Every root possesses (not essentially everything distinctive) zero, guna and vrddhi grades.

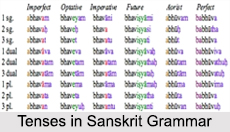

Tenses in Sanskrit Grammar

The verb tenses are devised and grouped into 4 systems as well as gerunds and infinitives and such tools as intensives/frequentatives, desideratives, causatives and benedictives deduced from more basic forms. These are based upon the different stem forms which are deduced from verbal roots and employed in unification.

There exist 4 tense systems in Sanskrit grammar, namely:

Present (Present, Imperfect, Imperative, Optative)

Perfect

Aorist

Future (Future, Conditional)

Nouns in Sanskrit Grammar

Nouns in Sanskrit grammar possess 8 cases: nominative, vocative, accusative, instrumental, dative, ablative, genitive and locative. The number of actual declensions however is an issue of considerable dispute. Panini had distinguished and delineated 6 karakas equivalent to the nominative, accusative, dative, instrumental, locative and ablative cases. They are as follows:

Apadana which literally stands for `take off`.

Sampradana stands for `bestowal`.

Karana stands for "instrument"

Adhikarana stands for `location`

Karman stands for `deed`/`object`

Karta stands as a signifying `agent`

Pronouns in Sanskrit Grammar

Pronouns in Sanskrit Grammar

In Sanskrit grammar, the first and second person pronouns are declined for the most part in a likeable manner, having by equivalence absorbed themselves with one another. The instances in which 2 forms are stated; the second is enclitic, bearing a substitute form. Ablatives in singular and plural of Sanskrit grammar can sometimes be broadened by the syllable -tas. Hence, mat or mattas, asmat or asmattas justify this very example of broadening a syllable. Essentialities in Sanskrit do not possess true third person pronouns, although its demonstratives satisfy this function in its place by bearing independently without a modified substantive.

There can be witnessed 4 different demonstratives in Sanskrit grammar, like: tat, etat, idam and adas. etat points towards a greater immediacy as compared to tat. While idam bears similarity with etat, adas pertains to objects that are more inaccessible than tat. eta is declined almost identically to ta. Its prototype is obtained by adding the prefix e- to all the forms of ta. As a consequence of sandhi, the masculine and feminine singular forms change themselves into esas and esa.

The enclitic pronoun ena is generally established only in a few indirect cases and numbers. Interrogative pronouns all start with k- and decline is the manner of tat, with the preliminary t- being replaced by k-. Only exception to this rule can be witnessed in the singular neuter nominative and accusative forms, which are both kim and not the likely predictable kat. For instance, the singular feminine genitive interrogative pronoun, "of whom?†represents kasyah. Indefinite pronouns always take shape when they are added by the participles api, cid, or cana after the fitting interrogative pronouns. All relative pronouns start with y- and decline in the manner of tat. The correlative pronouns are analogous to the tat series.

Compounds in Sanskrit Grammar

Another distinguished feature of the nominal system in Sanskrit grammar is the exceedingly common use of nominal compounds, which can sometimes be colossal like more than 10 words. Nominal compounds make their presence felt with numerous structures; although, when they are regarded morphologically, exhibit essentially similar characteristics. Each noun or adjective generally is in their (weak) stem form, with only the culminating element obtaining case inflection. The 4 principle categories of nominal compounds are as follows:

Dvandva (co-ordinative)

These consist of 2 or more noun stems, interlinked in significance with `and`. There exist primarily 2 kinds of dvandva constructions in Sanskrit grammar. The first is referred to as itaretara dvandva, a compound word stressing on enumeration, the sense of which are concerned with all its constituent members.

Bahuvrihi (possessive)

Bahuvrihi, standing for "much-rice", denotes a rich person, as in one who earns huge amounts to get much rice. Bahuvrihi compounds denote (by example) a compound noun that does not possess a header, more precisely, a compound noun that pertains to a thing which by its own is not part of the compound.

Tatpurusa (determinative)

There exists numerous tatpurusas one for each of the nominal cases and a couple of additional others in Sanskrit grammar. In a tatpurusa, the first component exists in a `case relationship` with another. For instance, a doghouse is an example of a dative compound, a house for a dog.

Karmadharaya (descriptive)

In this Sanskrit grammar phenomenon can be established through the relation of the first member to the last. They represent being appositional, attributive or adverbial, as in uluka-yatu, which represents a demon in the profile of an owl.

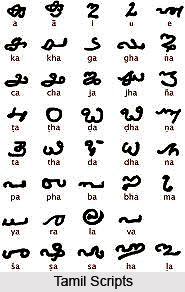

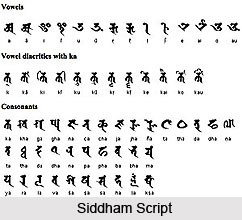

Vowels of Sanskrit Grammar

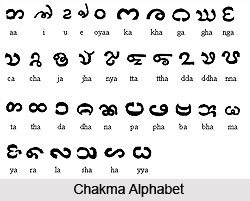

The vowels of classical Sanskrit are written in Devanagri, as a syllable-initial letter and as a diacritic mark on the consonant. In Sanskrit grammar, the long vowels are pronounced twice as long as their short counterparts. Also, there exists a third, extra-long length for most vowels. This lengthening is called pluti; the lengthened vowels, called pluta, are used in various cases.