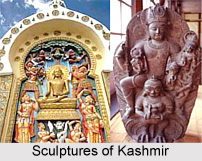

Sculpture flourished in Kashmir during the 8th and 9th centuries that reflected the power and influence of the kingdom at that time. The development of the arts during this period is attributed to the patronage of King Lalitaditya, who acquired the great wealth needed to support the large-scale production of art. Hinduism and Buddhism appear to have co-existed peacefully as evidenced by patronage of both Hindu and Buddhist structures. The Ushkur stupa bases and sculpture are reflections of the late Gandhara period to the west.

Sculpture flourished in Kashmir during the 8th and 9th centuries that reflected the power and influence of the kingdom at that time. The development of the arts during this period is attributed to the patronage of King Lalitaditya, who acquired the great wealth needed to support the large-scale production of art. Hinduism and Buddhism appear to have co-existed peacefully as evidenced by patronage of both Hindu and Buddhist structures. The Ushkur stupa bases and sculpture are reflections of the late Gandhara period to the west.

Sculptures of Bronze during Gupta Period

The post-Gupta bronze sculptures of Kashmir are well authenticated in literary sources of the time. Since so many are now known, their distinctiveness can be compiled with some confidence. Repeating items of dress, including the "Camail", a three-pointed tiny cape or bolero with an astoundingly long history, and an unexplained disc on each shoulder, point to elements of central-Asian origin possibly the "Sahis" among the population.

The posture and fabric of the few standing Buddhas reflect Gandhara renderings in stone, though other characteristics appear to point at a very late date. The first undeniably Kashmiri bronze known- the 6th century Vishnu in Berlin, is, like the stone Kartikeya in Srinagar, a Gandhara-Gupta blend.

= It must be early on account of the lion"s and boar"s heads, sprouting from the shoulders, rather than from each side of the god`s face and because there is no fourth face at the rear. The fabric of the dhoti, the moustached face, the crown and the lotus in the god`s right hand all possess Gandharan parallels.

The ingenuity of the Kashmiri bronze casters during the Karkot period (8th to 10th centuries) seems little less. Vishnu is depicted in several manners like on occasions seated on his vehicle, Garuda, or in a rare androgynous form (Vasudeva Kamalaja). The only Kashmiri image which can be dated with some accuracy, is the Lokeshwara consecrated during the reign of Queen Didda. It portrays that, by the beginning of the 11th century, modifications of style had taken place.

The ingenuity of the Kashmiri bronze casters during the Karkot period (8th to 10th centuries) seems little less. Vishnu is depicted in several manners like on occasions seated on his vehicle, Garuda, or in a rare androgynous form (Vasudeva Kamalaja). The only Kashmiri image which can be dated with some accuracy, is the Lokeshwara consecrated during the reign of Queen Didda. It portrays that, by the beginning of the 11th century, modifications of style had taken place.

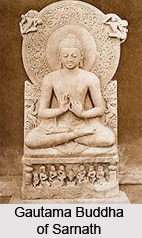

Sculpture of Lord Buddha

Buddhas too sit either in European manner; or else in "Padmasana" or "Lalitasana", with one leg pulled up, the other dangling down, on a wicker stool above the striking Kashmiri lotus with its smooth, fully rounded petals; or on a lion throne; or on cushions with textile motifs; or on a base elaborately carved with rocky forms in the Gupta fashion and populated with animals, devotees and donors.

Bronze Sculpture of Lord Vishnu

The biggest accomplishment of Kashmiri metal image making, however, is an extraordinary idol, an authentic metal arch, surrounded by the avatars of Vishnu, framed in the loops of an incessant swirling lotus tendril. At the zenith stands a multi-headed Vishnu, with a seated Shiva underneath. The foremost image is absent. It was evidently seated, from the inner contours of the frame, and might have been the Buddha considered by this time, one of the avatars of Vishnu.

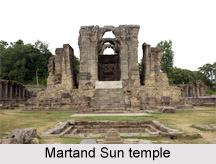

Sculptures of Martand Temple

The temple of the Sun at Martand, marvellously located near where the Lidder Valley opens into the vast Valley of Kashmir, is the biggest of the Hindu temples. It shares with a number of tinier, but less ruined shrines, the trefoil-arched niches, entryways and recesses underneath precipitously pitched triangular pediments, as well as the fluted columns and pilasters with a capital, syncretism between Buddhist and Hindu images. Later icons incline to be smaller and carved in a richly smoothened black chlorite. The "archetypal" Kashmiri Hindu image is a four-armed standing Lord Vishnu,

flanked by his embodied weapons and with a miniature bust of the earth-goddess (Bhu Devi), rising from a lotus at his feet. The god is four-faced with a boar"s head and a lion"s on both sides, and another head in low relief on the back of the halo. Sadashivas are also common. The sculpture from Pandrethan appears to span several centuries. The several vast and generally unpublished sandstone images in the Srinagar Museum, including some standing Matrakas, a Sadashiva, and a comical Kamadeva, in a sprightly, slightly fruity fashion probably belong to the 8th century.

flanked by his embodied weapons and with a miniature bust of the earth-goddess (Bhu Devi), rising from a lotus at his feet. The god is four-faced with a boar"s head and a lion"s on both sides, and another head in low relief on the back of the halo. Sadashivas are also common. The sculpture from Pandrethan appears to span several centuries. The several vast and generally unpublished sandstone images in the Srinagar Museum, including some standing Matrakas, a Sadashiva, and a comical Kamadeva, in a sprightly, slightly fruity fashion probably belong to the 8th century.

South of the Valley of Kashmir, Akhnoor in Jammu has created a number of miniature terracottas, mostly severed heads, possibly of the 6th Century. There is little proof in Punjab and north-western Pakistan, the chief assault route into India, of the monuments, which once have survived in plenty after the ultimate eclipse of Gandhara.