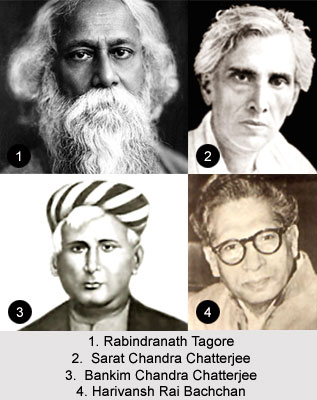

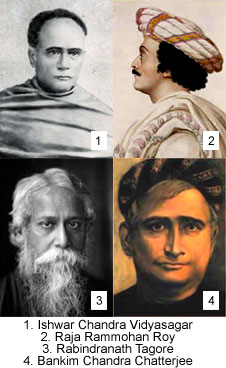

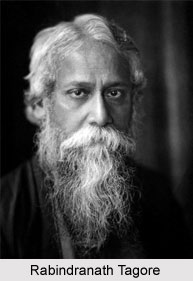

A remarkable example of the union of food and folk imagination in art can be seen in the rich and varied collection of chharas, songs and rhymes that are part of a long-lived oral tradition in Bengal. These chharas are rhyming couplets, similar to nursery rhymes. It is believed that women composed most of the chharas, since they centre for the most part on domestic matters. Meals or specific food items are frequently mentioned in the chharas as the means of enticement and appeasement. Only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were these rhymes collected and documented in a systematic fashion. Foremost among the rescuers of chharas were the poet Rabindranath Tagore and his nephew, Abanindranath Tagoreand later contributed much by the much famous Sukumar Ray. As is only to be expected, the chharas, even at their most fanciful or nonsensical, conjure up a faithful picture of an agrarian society where life was ritualized, expectations well-defined, the roles of men, women and children unquestioned and economic status often indicated by the food eaten every day.

A remarkable example of the union of food and folk imagination in art can be seen in the rich and varied collection of chharas, songs and rhymes that are part of a long-lived oral tradition in Bengal. These chharas are rhyming couplets, similar to nursery rhymes. It is believed that women composed most of the chharas, since they centre for the most part on domestic matters. Meals or specific food items are frequently mentioned in the chharas as the means of enticement and appeasement. Only in the late nineteenth and early twentieth centuries were these rhymes collected and documented in a systematic fashion. Foremost among the rescuers of chharas were the poet Rabindranath Tagore and his nephew, Abanindranath Tagoreand later contributed much by the much famous Sukumar Ray. As is only to be expected, the chharas, even at their most fanciful or nonsensical, conjure up a faithful picture of an agrarian society where life was ritualized, expectations well-defined, the roles of men, women and children unquestioned and economic status often indicated by the food eaten every day.

Themes of Chharas

The rhymes are replete with images of food, and key items recur in many forms. The region`s diet includes rice (the staple), fish, vegetables and milk and milk products. As a tropical land of many rivers, blessed with fertile alluvial soil, Bengal produced all these foods in abundance, but social and economic inequalities determined the proportion of individual access. In rhyme after rhyme, food is used to depict topography and climate, the interactions between family members (one`s own as well as the dreaded in-laws), prosperity or want and indoor and outdoor activities. It is not hard to imagine that women, who were in charge of the kitchen, were also the creators of these simple rhyming verses that so reflect their own concerns.

Fish and fishing are frequent themes. Many rhymes mention the son of the family (far more important than the daughter, who would, after all, merely get married and go away to her husband`s house) setting off on a fishing expedition. And numerous verses have the same recurrent image of two large fish (mi and catla, both of the carp family) leaping out of the river. The arcing motion of these graceful, silver-scaled, piscine forms struck generations of Bengalis as one of the most beautiful sights in their riverine land. In one verse, the mother ponders what nourishing food to give her son before he sets out on a journey and decides it will be prawns caught from the river, cooked with the eggplant she has grown in her garden. A charming image of the close relationship between human beings and their environment occurs in another chhara. A young boy, trying to catch a powerful boat fish (a freshwater shark), comes to grief when the fish capsizes the boat. Disappointed, the boy comes back to the shore. This amuses an otter so much that it gleefully cavorts in the river. The boy`s doting mother tells the otter to stop its antics for a moment and look towards the bank where her son, unperturbed by the loss of his boat, is dancing no less expertly. Another gem of a couplet, with an acute economy of words, evokes the image of one`s dream girl whose waist is slim and supple as a pankal fish (swamp eel, a common food fish in rural Bengal).

Fish and fishing are frequent themes. Many rhymes mention the son of the family (far more important than the daughter, who would, after all, merely get married and go away to her husband`s house) setting off on a fishing expedition. And numerous verses have the same recurrent image of two large fish (mi and catla, both of the carp family) leaping out of the river. The arcing motion of these graceful, silver-scaled, piscine forms struck generations of Bengalis as one of the most beautiful sights in their riverine land. In one verse, the mother ponders what nourishing food to give her son before he sets out on a journey and decides it will be prawns caught from the river, cooked with the eggplant she has grown in her garden. A charming image of the close relationship between human beings and their environment occurs in another chhara. A young boy, trying to catch a powerful boat fish (a freshwater shark), comes to grief when the fish capsizes the boat. Disappointed, the boy comes back to the shore. This amuses an otter so much that it gleefully cavorts in the river. The boy`s doting mother tells the otter to stop its antics for a moment and look towards the bank where her son, unperturbed by the loss of his boat, is dancing no less expertly. Another gem of a couplet, with an acute economy of words, evokes the image of one`s dream girl whose waist is slim and supple as a pankal fish (swamp eel, a common food fish in rural Bengal).

Rice flakes feature prominently in both the chharas and the folktales of Bengal because they are easy to carry for the intrepid hero setting out on his travels and because of their versatility in complementing many other foods. In the heat of a tropical summer afternoon, the flakes, soaked in cool water and accompanied by milk or yoghurt, ground coconut, summer fruits like banana or mango, made a meal that was both soothing and filling. Numerous verses mention such preparations made for the visiting son-in-law (the mortal deity who held the happiness or misery of the daughter in his hands) by his attentive mother-in-law. In one example, the mother-in-law makes a long-term undertaking. She will always give her son-in-law the major portion of her rice harvest after the rice is hulled, the whole head of any fish she cuts, rice on a plate of gold, numerous bowls full of different items to eat with the rice, a wooden platform to sit on and, of course, her beloved daughter.

Sometimes, however, no inducement or appeasement was good enough. The son-in-law could find insult where none was intended and leave his in-laws` home in a huff- possibly because he did not care for his wife and this was one more way for him show disregard for her family. One chhara describes such a son-in-law who refuses to eat the jamaishashthi meal because his in-laws have not met his expectations, despite giving him a whole boatload of paddy rice and another of the finest white, hulled rice. In the face of such churlish behaviour, a girl`s parents would naturally want to get back at the son-in-law. But they would never dare, for fear of bringing retribution on the daughter`s head in a society where neither divorce nor remarriage for a woman was possible. Instead, the grieving mother could only take metaphorical revenge by composing an angry and sarcastic chhara reducing the ritual of appeasement to nonsense. In this imaginary world where she can have autonomy over the son-in-law, she will serve him food most suited to his ungracious nature- rice accompanied by boiled shil (a large stone on which spices are ground), fried pieces of nora (a stone pestle used for the same purpose) and a spicy dish of spades.

The cook`s pride in her own art, especially in the art of preparing vegetables that the Hindu culinary tradition in Bengal is famed for, is also demonstrated in some delightful rhymes In one verse, the speaker mentions a lightly seasoned vegetable stew of baby pumpkins or gourds, vegetables that were considered the appropriate `cool foods` during the summer. In another, a rich merchant`s daughter boasts of her special recipe for a combination dish including eggplant, green bananas, striped gourd and climbing gourd. Beyond the normal pride of a good cook, this verse also illustrates the self-confidence, bordering on arrogance, of a woman from a wealthy family. One well-known verse is about an expert cook decrying the lack of skill of a young girl called Rani, who commits the heresies of adding hot chilli peppers to shukto, a mildly bitter dish, and ghee to ambol (a tart sauce, often tamarind-based, and always made with pungent mustard oil). It is likely that the unfortunate Rani is being castigated by one of her in-laws who could make life miserable for a new bride with barbed comments about her lack of skills in the kitchen.

The cook`s pride in her own art, especially in the art of preparing vegetables that the Hindu culinary tradition in Bengal is famed for, is also demonstrated in some delightful rhymes In one verse, the speaker mentions a lightly seasoned vegetable stew of baby pumpkins or gourds, vegetables that were considered the appropriate `cool foods` during the summer. In another, a rich merchant`s daughter boasts of her special recipe for a combination dish including eggplant, green bananas, striped gourd and climbing gourd. Beyond the normal pride of a good cook, this verse also illustrates the self-confidence, bordering on arrogance, of a woman from a wealthy family. One well-known verse is about an expert cook decrying the lack of skill of a young girl called Rani, who commits the heresies of adding hot chilli peppers to shukto, a mildly bitter dish, and ghee to ambol (a tart sauce, often tamarind-based, and always made with pungent mustard oil). It is likely that the unfortunate Rani is being castigated by one of her in-laws who could make life miserable for a new bride with barbed comments about her lack of skills in the kitchen.

Sometimes, the cook-artist`s perception of the lush vegetative world she inhabits expresses itself in innovative metaphors. Water lilies blooming in the still waters of a pond are compared to writing inscribed on paper; buds positioned around green lily pads are thought to resemble a dish of cooked greens garnished with boris, pellets of sun-dried legume paste. Sparse, haiku-like verses evoke specific emotions simply by positioning discrete images, including those of food items, next to each other. In one such verse, a sister`s longing for her absent brother is expressed through the contrast of torrential rain under an ominously black sky on the far side of a river, and a pepper plant loaded with vivid scarlet chilli peppers on the bank where she sits alone.

Perhaps the most repetitive food image in these chharas is that of milk and its many derivatives- yoghurt, curd, whey, clotted cream and ghee. Milk is an expensive commodity in modern India, something that only the well-off can afford. Mothers, even the poorest of them, will do anything to give their children milk or milk products. Rhyme after rhyme refers to young children, especially the favoured male child, being given bowls full of warm milk, and varied combinations of milk, rice, popped rice, bananas, mangoes, even jackfruit. In one verse, a mother calls her little boy, who answers from the kitchen garden that he is plucking greens for their midday meal. In reply, she dismisses greens as not being the right food for her beloved son, telling him instead to come inside for a meal of milk and bananas. So precious is milk that in many verses and folktales the cherished infant is referred to as a `kheerer putul` or a doll made of clotted cream. Another indication of the correlation between plentiful milk and familial prosperity is to be seen in recurring images of rivers or lakes of milk or cream.

Sometimes humour, verging on the black, is the tool for expressing the inadequacy of the provider in petting enough milk for the family`s needs. In one chhara a woman describes, tongue in cheek, how the one skimpy cupful of milk she has managed to buy must be stretched to cover everyone`s needs. First, it will yield two kinds of cream, as well as curds and butter, to be served at lunch and dinner. Then the two older sons will get some milk to drink, while the frothing top layer from the heated milk will be reserved for the baby. A sick relative, who suffers from a chronic cough, will get his share of the miracle fluid. Nor can the pet bird be ignored, it has such a discriminating palate that it refuses to eat birdseed. And who can forget that the head of the family must be given his share. As for the lady herself, she cannot possibly eat a meal without a bit of yogurt.

Thus the Chharas are delightful verses in Bengali literature which have existed mainly in the form of an oral tradition.