Introduction

History of Punjabi Theatre, in its early days was rhetorical, with emotions and sentiments having great importance. Theatre activity in Punjab was triggered by militancy. Most of the theatre groups concentrated on the Punjab problem and churned out scripts and staged plays on this problem. Hence, Punjabi theatre remained a localized affair with no distinctive character of its own.

History of Punjabi Theatre, in its early days was rhetorical, with emotions and sentiments having great importance. Theatre activity in Punjab was triggered by militancy. Most of the theatre groups concentrated on the Punjab problem and churned out scripts and staged plays on this problem. Hence, Punjabi theatre remained a localized affair with no distinctive character of its own.

Gursharan Singh, the most notable of the artists, took his message-oriented plays from village to village and warned the masses of the dangers of religious fundamentalism. His plays written and enacted during this period were repeatedly applauded and enjoyed by the common people.

Punjabi Theatre Between 1931 and 1947

Punjabi theatre between 1931 and 1947 was mainly dominated by playwrights of the modern Punjabi theatre. The writers have brought vigour and freshness to Punjabi theatre and with them began the trend of progressive writing.

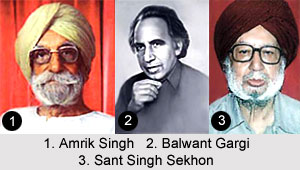

Punjabi theatre between 1931 and 1947 was mainly dominated by playwrights of the modern Punjabi theatre. Harcharan Singh, a pioneering force in Punjabi theatre, and the playwrights who followed his lead, added quantitatively to the body of dramatic literature in Punjabi, but they have offered little by way of quality, which appeared only when stalwarts like Sant Singh Sekhon, Balwant Gargi, and Amrik Singh (1921) made their contribution. These writers have brought vigour and freshness to Punjabi theatre. With them began the trend of progressive writing. Sekhon has given a new dimension to Punjabi theatre by committing the genre to a dialectical interpretation of contemporary reality.

Punjabi theatre between 1931 and 1947 was mainly dominated by playwrights of the modern Punjabi theatre. Harcharan Singh, a pioneering force in Punjabi theatre, and the playwrights who followed his lead, added quantitatively to the body of dramatic literature in Punjabi, but they have offered little by way of quality, which appeared only when stalwarts like Sant Singh Sekhon, Balwant Gargi, and Amrik Singh (1921) made their contribution. These writers have brought vigour and freshness to Punjabi theatre. With them began the trend of progressive writing. Sekhon has given a new dimension to Punjabi theatre by committing the genre to a dialectical interpretation of contemporary reality.

Some of his very well known plays include Kalakar (The Artist 1946), Moyian Sar na Kai (Gone and Forgotten), Bera Bandh Na Sakyo (You did Not Bind the Logs of the Float), Narki (Denizens of Hell, 1952), Damyanti (1962), and Mitter Pyara (The Dear Friend). It is generally believed that Sekhon has failed to write plays meant to be staged, and his works do not go beyond intellectual discussions, which, of course, are stimulating. His characters are automatons and devoid of any physical action, but still his writing offers an exciting fare for mature and lively debate.

During this period, there seemed to have developed a cleavage between literary drama and drama meant for the stage. The plays of Sant Singh Sekhon, though impressive, were scarcely staged. Defending his plays, he argued that they could not be staged for they represented times ahead of him. The existing theatre was not adequate to produce his plays because of its limitations. On the other hand, some Punjabi critics characterized these plays as literary plays at best, having no potential to turn into a stage reality. Roshan Lal Ahuja accepted that there could be both kinds of plays, literary meant for reading only and others worthy of stage production.

Gargi, under the impact of progressive movement, wrote a number of plays with a Marxist slant - notable among these are Ghuggi (The Dove), Biswedar (The Feudal Lord), SailPathar (Still Stone), Kesro (Name of Woman), and Girjhan (Vultures, 1951). These plays are on themes such as the world peace and movement, the agrarian struggle, national reconstruction, and polemics of committed art. Gargi is also an author of a scholarly treatise on Indian stagecraft entitled Bharti Drama, which won him a Sahitya Akademi Award.

Among the older generation, Kartar Singh Duggal, a leading fiction writer, wrote plays that have been produced mainly by All India Radio. He is credited with developing a form of the radio play in Punjabi. To meet the needs of the radio play, he uses his characters as symbols. His play Puranian Botlan (The Old Bottles) is a meaningful critique of the unscrupulous behaviour of the urban middle class.

Punjabi Theatre Between 1947 and1980

In this period, Punjabi Theatre incorporated playwrights of the pre-independence period who continued writing after independence. They wrote plays on the problems of rehabilitation of refugees during the Partition of India which introduced a new themes and techniques in their plays.

Punjabi Theatre Between 1947 and1980 incorporates playwrights of the pre-independence period who continued writing after independence and some, like Gurdial Singh Khosla, Harcharn Singh, Kartar Singh Duggal, and Sant Singh Sekhon, wrote plays on the problems of rehabilitation of refugees following in the wake of partition of India, yet a group of young writers namely, Amrik Singh, Harsaran Singh (1929-94), Gurcharan Singh Jasuja (1925), Surjit Singh Sethi (1928), Kapur Singh Ghumman (1927-84), and Paritosh Gargi (1923), introduced a few new themes and techniques in their plays.

National School of Drama (NSD) and the Punjabi Theatre

Only in the 1960s did the theatre movement in the regional languages attain maturity and professional skill. The National School of Drama, established in Delhi in the early 1960s, became a strong centre for bringing about a purposeful dialogue among theatre folks of the different regions of India. With coming into contact with the theatre being done elsewhere in India, Punjabi theatre found a new orientation in the Punjab and Delhi and Bombay. It had an opportunity to avail itself of the services of well trained professional theatre artists like Harpal Tiwana and his talented wife, Neena, Bansi Kaul, Suresh Pandit, Gurcharan Singh Channi, Devinder Daman, Sonal Mann Singh, Balraj Pandit, Kewal Dhaliwal, Kamal Tiwari Mahender, Navnindra Behal and Rani Balbir Kaur, who have brought into it a new vitality and vigour.

The establishment of the departments of Indian drama and Asian theatre at Punjab University, Chandigarh, and speech and drama at Punjab University, Patiala, under the guidance of two theatre stalwarts, Balwant Gargi and Surjit Singh Sethi, respectively, had led to some bold experiments in theatre. In the 1970s, Prem Julundry, with his Sapru House shows, regaled middle-class Punjabi audiences in Delhi. These shows, a craze of those times, offered what may be termed hilarious adult comedy, which were also called laugh-a-minute sex comedies. These Punjabi farces with salacious titles have been attacked, defended, even threatened, yet they were big box office hits.

In this very period, Punjabi theatre started having its impact, for some of the theatre groups made a serious effort to free themselves from the bonds of tradition. The Delhi Art Theatre of Shiela Bhatia, Gursharan Singh`s Amritsar School of Drama, which later took the name of Chandigarh School of Drama after his moving to Chandigarh, Balraj Pandit`s Natakwala, and Atamjit`s Kala Mandir, first at Amritsar and now at Mohali, have combined dramatic dexterity with ingenious devices while exploring new modes of expression on stage. Ajmer Aulakh has evolved a new, robust theatrical idiom from the folklore of Punjab. Devinder Daman and Jaswant Damathe, a director-actress, husband-wife team, have, through their Norah Richards Rang Manch, introduced new modes of action in religious-historical plays.

Punjabi Drama and Theatre from 1980 Onward

From 1980, Punjabi theatre passed through most difficult times. In this period, the people of Punjab suffered the most painful conditions of reckless killings and tensions between the two major religious groups of Punjab, Hindus and Sikhs. There was an atmosphere of total darkness and dissolution, with ever-increasing terrorist activity of looting and killings and fake police encounters, with women widowed and children orphaned.

Following the partition, the theatre settled in areas like Shimla, Jalandhar, Patiala, Amritsar, Delhi and later, Chandigarh. Nowhere could it make its presence felt. When Punjabi theatre came into contact with the theatre of other regions of India it found a new direction in Punjab, Delhi and Mumbai. The establishment of the departments of Indian drama and Asian theatre at Punjab University, Chandigarh, and speech and drama at Punjab University, Patiala, under the guidance of two theatre stalwarts, Balwant Gargi and Surjit Singh Sethi, respectively, has led to some bold experiments in theatre.

Contemporary Punjabi Theatre

Contemporary Punjabi theatre talks of the prevailing atmosphere in the theatre world of Punjab. A significant section of Punjabi and Hindi theatre (which emerged in the nineteenth and early twentieth centuries respectively) has engaged itself with subjects derived from myth, legend, and history of India.

The choice might have been partly a pragmatic one because the narratives from the past provided a structure of shared beliefs; yet it was also a conscious attempt to infuse the country with cultural vitality and to awaken the national spirit. The past was invoked to portray models of endurance, self-sacrifice, courage, and undaunted resistance in the characters of Sita, Savitri, Abhimanyu, Maharana Pratap, Rani Padmini, and others to inspire the writers` countrymen to fight against oppression and colonial rule. The return to the past was inevitably characterised by reformed romanticism which countered the colonizer`s image of the inferior, the barbaric and the uncivilized of the colonized. However, in the post-colonial phase, the use of myth, legend, or history is problematic and multidimensional; in addition to using the past to clarify and comment on the present, playwrights (particularly from the sixties onwards) present a critique of their own cultural traditions which they confront, question, subvert, and at times even reject.

Legends of contemporary Punjabi theatre speak about the various aspects of contemporary Punjabi theatre. Legend, despite its specific differences from myth, performs similar psycho-social functions. Like myth, legend is a cultural construct which records, presents, and further regulates and validates the moral system of a society.

The legends of the Punjab, going back to medieval times and before, are essentially patriarchal in their values and structure, whether as the legends of love or those of morality which posit models of ideal human conduct. The woman stands either marginalized or misrepresented; at the most she is a person of no consequence who is unfit to be noticed, and at her worst she is an evil, wicked temptation ever ready to entice man, someone against whom the virtuous man should carefully guard himself.

While playwrights of an earlier age were content to focus on the images of woman glorified in the myths, of woman steeped in endurance, self-sacrifice and steadfast virtue (for example, Brij Lal Shastri`s plays Savitri and Sukanya (1925) derived from the Mahabharata), playwrights in the postcolonial phase focus instead on the image of the wronged woman and recreate legends from her point of view. Even though drama in the Punjab, as in the rest of India, remains men`s forte, the contemporary renderings of the traditional patriarchal narrative take a feminist form in a bid to make them more realistic, just, and open to question and analysis.

One of the numerous popular love legends of the Punjab is the legend of "Heer Ranjha" of the sixteenth century. In various renderings of the legend and in proverbial utterances, Sahiban is a byword for the infidelity of woman. Contemporary playwrights not only redeem these women from the charge of infidelity and betrayal, but also present them as more complete, complex, and humane persons in comparison with men, who, blinded by their egos, have only a partial understanding of life and who are, in fact, responsible for women`s suffering. While maintaining the broad outlines of the narratives of the past, by slightly shifting the emphasis in character or incident or by filling in some gaps the playwrights attempt to draw attention to certain unjustified assumptions and fallacies in the legends.

In his one-act play Heer da Dukhant (The Tragedy of Heer, 1982) Harsaran Singh focuses on the moment when Ranjha reaches Heer`s in-laws` house, highlighting how Heer has been wronged both by her husband and by her lover. Working on the argument at greater length in a later play Heer Ranjha (1990), Harsaran Singh dramatizes the entire narrative and reveals how Heer is in fact wronged by all the men in her life, by her father who forces her to marry Saida in the name of family honour even after she has revealed the true identity of Ranjha as the son of a chieftain, by her lover who failed her when she offered to elope with him but later reaches her in-laws` house in the guise of a fakir, and by her husband who neither fulfils the duty of a husband in that he does not protect her from the fakir nor accepts her leaving the house and runs after her with a sickle to murder her.

Ajmer Singh Aulakh, in his one-act play Bal Nath de Tille Te, 1978, vindicates woman by giving Ranjha a language different from that in the legend. Woman`s love is glorified as the love of God. The play recounts the moment when Ranjha goes to Guru Bal Nath to become a Jogi after Heer is married to Saida.

Several playwrights have been fascinated with Sahiban`s character that, unlike other Punjabi heroines, is torn between the contrary pulls of natural desire and filial commitments. They variously have tried to redeem her from the charge of betrayal.

The biased and simplified discourse of the legend becomes complex and more realistic in modern plays, wherein women grow into fully developed characters and cease to be mere `functions` in the grandiloquent design of the narratives glorifying man. Even though most of these plays coincide with the revival of the feminist movement in the West, they are not the result of any women`s movement in the Punjab. Interestingly, all these feminist variations of the traditional discourse are created by male playwrights, with the exception of Sundran. The distinction is significant, though. The feminism of the male playwrights forms part of their larger, more generally humanistic vision, which believes in the essential humanity of all people and subscribes to an ethos of dignity, respect, freedom and justice for all human beings; when these principles are violated, the playwrights use their dramas to speak for the violated victim. With Manjit Pal Kaur the rendering afresh of the legend is a conscious and more specifically ideologically feminist statement. As a result, while other protagonists, despite their protest and rebellion, continue to remain victims of patriarchy, Sundran transcends the patriarchal structure of the legend: she would not commit suicide, she is `incomplete` but not utterly dependent on Puran, her sexuality and motherhood are realised at her own will and not at the dictates of man. Even more significantly she substitutes for the patriarchal order of binary oppositions of the oppressor and oppressed, the ruler and the ruled, an alternative vision of complementarily of man and woman where both can live in mutual harmony and reciprocity instead of one having to suppress the other for one`s own being.

To impart a dramatic structure to the meandering narratives of the legend, these playwrights turn to indigenous theatrical traditions, both classical and folk. From Sanskrit drama they derive the characters of the Sutradhar (i.e., the director, controller or stage-manager, though literally it means `one who holds the strings`) and Nati (actress) and adapt them to individual requirements. In Sundran they are given the traditional role of introducing the play and stand outside the body of the play. In Luna, Shiv Kumar extends their traditional role by giving a long first scene to them. They figure as creatures from heaven that on one side in rich poetic delight dwell on the beauty of this earth and on the other question the `irrational` cruel practices like animal sacrifice to be performed by the king. In Mirza Sahiban, Balwant Gargi gives the Sutradhar a recurrent appearance in the play, and he punctuates the action with his comments.

From the folk theatres the playwrights derive a narrator-like character to sum up the action and to direct the audience`s attention. For example, the Dhadi, a folk-singer who traditionally sang these legends, is a frequent choice, serving as a chorus who sings excerpts from the legend while the action progress, sometimes in accordance with the legend and sometimes contrary to it. Gargi makes a pronounced use of this character. Others, like Harsaran Singh in Heer Ranjha, Ghumman in Rani Koklan, and Bahrla in Sahiban, prefer to use a Voice, which creates the effect of timelessness, similarly to narrate the legend; or to sum up and comment on the action; or to externalize the feelings of the characters. In Rani Koklan a chorus is also used, first to sing excerpts from the legend and then to counter it by pointing to Koklan`s experience. Scenes flow one after the other with simple alternation of darkness and light. Like the poetic narratives of the legends, many of these plays are poetic plays, e.g. Luna, Sahiban, Sundran, and Aulakh`s one-act plays. Even those written in prose are frequently interspersed with excerpts from the legends and snatches of folk songs and closely maintain the poetic rhythm of the legends, while occasional introduction of folk dances like Gidhha and Bhangra add to the folk atmosphere. Engaging themselves with the paradigms of the oppressor and the oppressed in the larger socio-cultural context, the post-colonial playwrights in the Punjab thus realize their creative instinct in their own native linguistic and cultural context by updating the traditional discourses as well as theatrical conventions.

During the 1940s, there emerged a significant Punjabi theatre in Lahore. But the partition of the country was responsible for checking its growth. Uprooted from its nuclear cultural centre of Lahore, theatre activity received a serious setback when it dispersed to Shimla, Jalandhar, Patiala, Amritsar, Delhi, and later, Chandigarh. Nowhere could it make its presence felt. In all these places, Punjabi theatre remained a localized affair with no distinctive character of its own.

Punjabi Theatre and Its Present Position

The early Punjabi theatre catered primarily to the urban middle class, and its intent was to bring about social reform. Whatever the conflicts presented, these plays focused on the domestic and the romantic. The characters were generally stock types, and the denouement proceeded on familiar lines. According to Sant Singh Sekhon, Punjabi theatre in its early days was rhetorical, with emotions and sentiments having great importance.