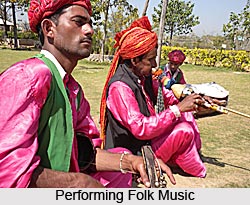

Rhythm or tala in folk-music is mostly a less discussed subject, because talas are played to folk-songs on percussion and other instruments by singers themselves or refrainers who do not generally undergo any methodical training. They learn through spontaneous predilection of their own and perform rhythm habitually. Thus, when folk-music is discussed, the rhythm never gets importance, stress being laid on other elements, words and tunes. The reason is obvious. The system of elaborate training on percussion instruments, as in vogue in general classical music, is unknown in the rural musical world. The popular Vaishnava devotional songs, familiar in the farthest corners of villages of Bengal and Assam, are provided with spontaneous khol playing for which khol players receive necessary training. But khol playing to folk-songs is adapted automatically, rather by imitation, by folk-singers without much initial toil. Thus, the system of training of percussion instruments is absent in folk-music. But, on the other hand, the most imposing part of it is that the direct and loud play of rhythm produces simple and blatant forms.

This, again, maintains an unrecorded tradition based on an unnoticed methodology. On the other hand, rhythm predominate folk-music, because, the tala accompanist handles his instrument producing loud and bold effect, hardly balanced and controlled. Thus, free and loud uncontrolled voice always combines with free and loud rhythm played to folk songs. Rhythm, played on a very particular percussion instrument, is indicative of specific folk-song or music.

Rhythm is, thus, rooted to a particular type of music. For instance, a particular tala played on dhol signifies music of kavi, tarja, etc., of West Bengal, and such other items indicate bihu of Assam. Talas on khamak recital proclaim a distinctive setting of Baul singing. Talas played on khol and kartal (cymbal) indicate the performance of devotional music. Swinging rhythm on dhol and kansar declares marriage or various puja festivals of West Bengal. On the whole, expressions of rhythm including the instrument played stand on the foreground of music of the rural people. They comprehend the spirit for traditional listening and participation with the music.

It is interesting to note that forms of rhythm of folk-music are harmoniously developed with the nature of language used in songs. Spoken words and dialects, rather vocabularies, used in rhythm are adapted naturally for the purpose. Even raucous words and naive expressions are observed to have a sort of sequence with rhythmic forms, and these two combine inseparably in songs.

Musical rhythm is deeply rooted in the language of a folk-song. Dialects of pure local nature, which characterize a song, preserve certain phonetic peculiarities in pronunciation of words. When these songs are sung, continuity of music is maintained through the lingual expression set to a peculiar rhythmic form. Vowels like a, i, o, e, which are elongated in pronunciation with occasional break, help the rhythmic formations; sometimes vowels or consonants are individually introduced.

Often in songs raucous vocabularies mix up with fists of loud expressions and hard stroke of percussion instruments. In most performances it is found that the tune is subservient to the loud rhythm, and is recited mere rhythmically than tunefully. The swing of rhythm is, thus, confused with music, that is, mere rhythmical forms are accepted as music. Free use of rhythm, played on loud percussion instruments, makes the most of music, the real music often remaining frail or feeble.

Rhythm appears to be the primary element of music. It came into being along with the throbs of life, even before musical notes were discovered. It is presumed that the oldest mother of the unknown past must have wanted to swing her child with the sing-song humming and thus rhythm emerged out of it. Or it might be that man observed rhythmic sounds in nature - in rains, waterfalls, etc., which he imbibed somehow, or he devised rhythm along with his own stepping. Rhythmic sound of rain drops on earthen pots, plants, etc., might have roused a similar sense of rhythm in man. There is an instance of Sati`s devising musical rhythmic instruments in Bharata`s Natyashastra. Sounds raised by dropping of torrential rain on leaves of lotus inspired the mind to invent the Puskar Vadya. Nature helped man a lot in introducing rhythm in walking which developed into dancing steps and at length its conversion into harmonious beating of drums with dancing steps. This is how rhythm was required for natural purpose even before the musical notes were known to him and development after music came into being. It may be held that the idea of rhythm passed through numerous stages when rhythmic musical instruments were introduced.